— Bob Thaves, Frank and Ernest (1982)

We are on the cusp of a second She Roars, a conference that will celebrate and, with great credit to the organizers, challenge the Princeton alumnae body. The first She Roars, which coincided seven years ago with the 50th anniversary of the enrollment of the first full-time woman Princeton student, Sabra Follett Meservey *66, was a huge hit with an impressive 1,400 or so attendees. It led the way to consideration of how reinforcing women in their own concerns could benefit everyone. Those poor souls who attempt to conflate diversity with divisiveness and fragmentation would be well advised to pay attention to that occasion, and this one, to get into their thick heads that support for the substantive improvement of any segment of a pluralistic society is eventually a boost to everyone else. If the histories of both Princeton and the United States show nothing else, it’s that game theory rules, it’s not a zero-sum game, and the game we’re in has thousands of win-win (and lose-lose) solutions.

The second She Roars comes on the eve of the more high-profile 50th anniversary: the decision of the trustees in April 1969 to admit women as full undergraduates to the college and in the process knowingly change Princeton forever. While that occasion (the vote was 24-8, so don’t let anybody tell you this was a done deal) and the hoopla surrounding the acceptance letters to the prospective women of ’73 are a high-profile part of our folklore, some of the facets of Princeton’s journey to coeducation are not well-known. A look at them will be illuminating, if only to marvel that Bob Goheen ’40 *48 got anything else done as president (which he decidedly did) as they were all unfolding.

A couple pieces we’ve already touched on in columns regarding my friends the nine women of the Class of 1970, and the Critical Language program of which they were a part. To recap briefly, the Defense Department decided to fight the Cold War in part by supporting studies in uncommon foreign languages, including strategically pivotal ones such as Russian (and Tamil). The few places that had excellent programs, including Princeton, welcomed visiting students in their junior year for immersive study, no matter their gender. So in 1963, we welcomed a few women students onto campus who morphed into the nine, who after formal transfer in 1969 graduated the year following.

We should note explicitly as well the few hearty women then enrolled in the Graduate School, who went about their fishbowl tasks with stoic self-control; even after their odds-defying admission they faced all sorts of insipid roadblocks, from housing discrimination to library access (“we don’t lend books to dates of students”) to paperwork holdups. Meservey, who was already teaching history at Douglass College (part of Rutgers) when she applied in 1961 and so had the significant legitimacy leverage to be the test case, had to wait three years for her Ph.D. diploma after her degree completion because no one could find the time to translate the Latin citation into the feminine. With yet another nod to our good friend April Armstrong *14 over at the Mudd Manuscript Library Blog, I encourage you to see other such tales from the graduate students of the ’60s, including the 14 astonishing women who earned their Ph.D.s before the trustees even admitted undergrad women.

The report requested by the board of trustees in June 1967 from its campus-wide committee on educating undergraduate women, chaired by economics professor Gardner Patterson, was the critical formal plunge into the issue. The group, refusing to be rushed, took 14 months to analyze anything reputable they could find regarding single-sex vs. coeducation, and in the end issued a forceful and crystal-clear document, The Education of Women at Princeton, that was made public here in PAW on Sept. 24, 1968. A model of research thoroughness, including 34 charts regarding a basically yes/no question, it stands up perfectly well even today with its two brusque conclusions. First, the social atmosphere on campus and the academic atmosphere would be significantly improved. And second, Princeton was losing desirable people as an all-male institution, and that would only get worse.

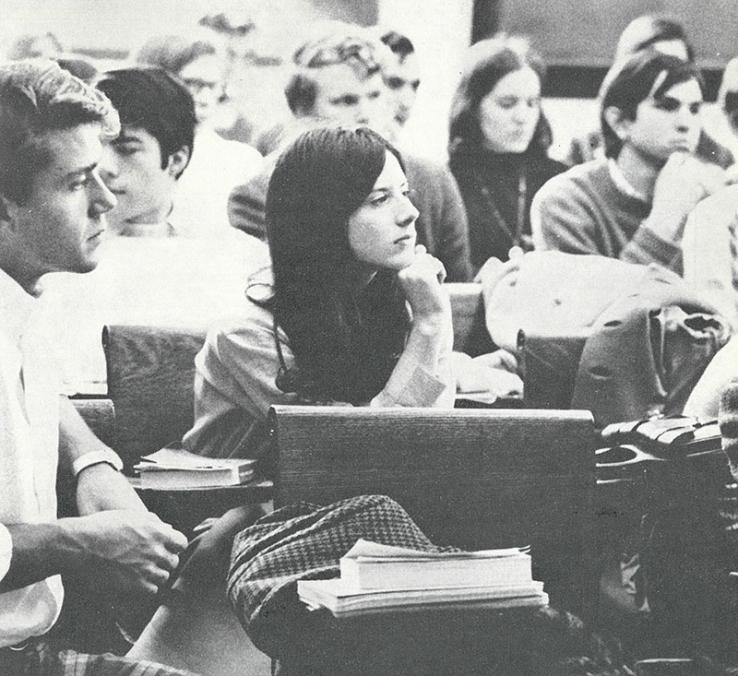

Then there was Coed Week. Conceived in late 1968 by the undergrads as something between a chance for the male student body to demonstrate its couth and for the trustees to be dazzled by the virtues of the brave new ’60s world, it was set for Feb. 9-14, 1969, after the board accepted the Patterson Report’s conclusions but before it greenlighted implementation. While the ad hoc Coed Week committee tried to finagle free food from Commons and the clubs, and rooms from the students (the idea was to vacate for the week, not share, by the way), they sent notices and applications to 18 women’s colleges to see who was interested into going to classes and meals and living on campus for six days. Hoping to get 200 or 300 “girls” to campus, the committee ended up staring at more than 2,500 applications, some of which came in on postcards since forms had long since run out. As seven inches of snow fell on Princeton, some 550 women descended as well, pitching in for a week of classes, “normal” socializing, and extracurriculars, and (a bit confusingly) a weeknight mixer and a Valentine’s candlelight dinner at the Student Center. Professor Steve Klineberg, whose SOC 212: Social Structure, Culture and Personality had already become the most popular course in recorded history with 491 men enrollees before Coed Week, had to move to Alexander Hall to accommodate the guests. Everyone seemed cheery, and disaster was avoided, but as one organizer said afterward with a grin, “I hate women. They’re just people.” The press, however, was huge.

Meanwhile, trustee Harold Helm ’20 was conducting a roadshow with Goheen to 25 different cities to sell the Patterson Committee idea to alumni and calm some of the resultant roiled waters. Questions abounded, but as a local alumnus minister at the close of the huge and lengthy Princeton Area Alumni meeting pointed to Genesis 2:18, “And the Lord God said: It is not good that the man should be alone.”

And so here we are, 50 years and two alumnae Supreme Court justices later. That’s the official story.

I would, though, like to mention three important things that you would have missed if you weren’t around in the ’60s, because while their emotional impact on Princeton may have been more informal and less clearly documented, they were notable indeed. And their effects on coeducation here are profound.

The first is the pill. The initial FDA approval for the female birth-control medication in 1960, and its universal clearance by the Supreme Court in 1965 — when it was already the most-used contraception method in the country — essentially changed the social and cultural norms between men and women, and the power of the latter over their own lives. Thus American women were far more powerful in 1969 than they had been in 1961. Trustees notice power.

The second is the Riot of 1963. A completely pointless, juvenile swath of hooliganism the Monday after Houseparties that spilled over into town (always a huge no-no), it unfortunately coincided with brutal attacks on civil-rights demonstrators in the South, underlining the sophomoric idiocy on campus. At the same trustees’ meeting where the Critical Languages program was approved, President Goheen reported on the “mindless, faceless, inhuman mob” that resulted in 11 full-year suspensions, 36 shorter ones, and 13 convictions in local court; the trustees firmly supported the discipline. It turned out the mob was disproportionately preppies and legacies. If you couldn’t smell social change in the wind after that, you needed a nose job. Trustees hate embarrassment.

And then finally there’s Agnes Scott. Well, not her actually — she was a Presbyterian Scots-Irish immigrant in the early 19th century — but the small women’s college named for her in Decatur, Ga. The women of Agnes Scott ended up on NBC in the brainiac hit of the era, The GE College Bowl, against returning champ Princeton on March 9, 1966, one year after the Tigers made it to the NCAA basketball Final Four. It was obvious from the outset it was an even fight. After a 50-0 Tiger runout, the Scotties — yes, that’s their nickname — led 100-60 at the half, before Princeton patiently worked back to a 215-190 lead with just seconds to go. But the Scotties won a 10-point tossup on physics and then faced a 20-point question on Balmung and Durendal. With a second to go, Scottie Karen Gearreald remembered they were legendary swords. Final: Agnes Scott 220-215. Oh, yes: Gearreald was also blind. Trustees don’t like losing.

She Roars has plenty to do and plenty to celebrate, but just maybe in addition to recognizing the brave women grad students of the ’60s, the resilient undergrad women of the early ’70s, and the thousands of highly accomplished alumnae out there, they might want to raise a mint julep or two to the fine ladies of Agnes Scott, who long ago made their impression on Princeton with the strength of Balmung and Durendal.