Grades at the University have been rising steadily since Princeton reversed its “grade-deflation” policy in 2014–15, but student stress levels and requests for grade changes have also been increasing.

“We are aware of the increase in student anxiety — for many reasons — across the University, and really across American culture,” Dean of the College Jill Dolan said at a meeting of the Council of the Princeton University Community in September. “The increase in requests for grade changes seems to say that our changed policy hasn’t necessarily abated any of that anxiety about grades.”

Instead of a centralized grading policy with numeric targets for A grades set in place by the University, departments have been responsible for developing their own grading rubrics since the new policy was adopted in 2014.

Undergraduate Student Government president Rachel Yee ’19 said that anxiety is “pretty pervasive” on campus, especially for students who are hoping to pursue a postgraduate education or who plan to apply for a job that requires a high GPA.

“I think that there’s always a level of comparison,” Yee said. “You also don’t want to feel like you’re doing poorly compared to your peers.”

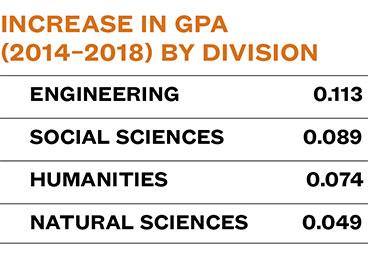

The average GPA rose to 3.46 in 2017–18, up from 3.39 in 2014–15, when Princeton adopted its new grading policy. By comparison, the average GPA in 2004–05 (the first year of the so-called grade-deflation policy) was 3.30.

Humanities courses had the highest overall average GPA last year, with the average grade being about 3.6. Princeton’s rising GPAs are in line with a national trend of grade inflation, Dolan said.

“Most significantly, what’s changed is that A grades [at Princeton] have risen almost proportionally to how B+ grades have gone down,” said Dolan. “The shift has been away from using B+ as a grade and toward using A as a grade.”

The number of requests for grade changes is up sharply since fall 2014, when 278 requests for a change in final grades were submitted by faculty members to the Office of the Dean of the College. The number of requests rose to a high of 429 in the fall of 2016, then declined in the fall of 2017 to 392. Almost all requests by professors for grade-changes are approved since grading and evaluation “are a prerogative of the faculty,” University officials said.

“Is this because the fact that faculty are now responsible for their own grading standards makes them vulnerable to students’ requests for having their grade changed,” Dolan asked, “or is it that faculty aren’t being sufficiently clear about what their grading standards are and how they are assessing students? It’s probably a bit of both — but we’re very concerned to understand the reasons why this is happening, and also to change it.”