“The book to read is not the one which thinks for you, but the one which makes you think.”

— James McCosh

In the spring, we looked at James McCosh’s training and development as a preacher, teacher, church radical, and educator in Scotland and Ireland. We also noted the serendipitous nature of his hiring in 1868 as Princeton’s 11th president. We left him and his talented wife Isabella at anchor off New Jersey.

From the day he stepped onto campus (conveniently so dubbed by his Scots spiritual forebear, John Witherspoon, 100 years prior), James McCosh was ready and eager to be an American educational leader. A wholesale transformer of reality, however, maybe not so much. I mean, there is a certain level of truism about educational institutions, or so you would think: You get a bunch of students into a room; you add an instructor who gives tests, corrects and grades the tests; the students complain; rinse; repeat. How surprising can this be?

Given his extended triumphal tour of the United States in 1866, just two years prior to his selection as Princeton president, you would think McCosh would have suspected any number of things, but the situation the day after he moved into the redecorated president’s house was clearly a bit of a shock. While the College remained the flagship of Presbyterian intellectualism in the United States — while the seminary down the street was the unbending bastion of the Old Side of the church — it had missed countless opportunities under lackluster president James Carnahan 1800 from 1823 to 1854, and was saved only by John Maclean Jr. 1816 as vice president from 1829 to 1854 and president from 1854 to 1868. But as president, Maclean suffered through the second catastrophic Nassau Hall fire in 1855 and then the decimation of the student body by the Civil War, losing a cadre of southern Presbyterians who would never reappear in the same numbers.

McCosh in 1868 faced a slim and not particularly intellectual student body of 281; a faculty of 16, mainly elderly alumni; a stodgy board of trustees, appointed to their positions for life; and an American higher education environment, most notably focused on Harvard, that was rapidly leaving the little College of New Jersey in its rearview mirror.

Part of this stemmed from his ability to see the secular world clearly and incorporate its rapid changes into his own philosophy and teaching. Princeton, from 1868 to 1888, absorbed a vast array of societal and scientific developments, from Darwin (McCosh saw no conflict between evolution and Christianity) to electricity to astronomy to the big railroads to modern financial conglomerates to industrial fortunes and the new moneyed class to the new crazed national interest in athletics and sporting events. The idea that he used all of these in the service of turning a little college on the high road into a University regarded by 1896 as one of America’s Big Three — and so seen ever since — while remaining clearly the most beloved man on campus, is a marvel to behold, even 150 years later.

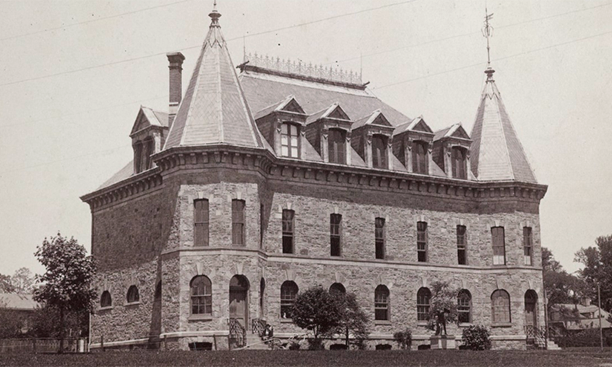

You name it, McCosh changed it, or at the least thought about changing it. For starters, there was a curriculum that could well be described as drab if not backward. He instantly trashed the existing four-year schedule of compulsory courses and set up broad requirements for the first two years, followed by a range of electives that he spent his entire tenure expanding. He taught philosophy and psychology; he featured the skills of his few stars, like Arnold Guyot in geology and Stephen Alexander in astronomy; and he added courses in everything from economics to English literature. This in turn required a wholesale rework of the “library,” which to his shock when he arrived was open one hour … per week. By the end of his term, the beautiful, accessible new Chancellor Green Library (funded by railroad money) stood as a monument to inquisitiveness and was the second-largest college library in the country. And he was publicly debating curriculum one-on-one with Harvard’s Charles Eliot, to national acclaim.

The attractiveness of the faculty and curriculum could go only so far in drawing students, so McCosh pitched in to help develop new sources of talented scholars to replace the Southerners who would never return en masse. Lacking the prep-school feeders that Harvard and Yale had, Princeton started its own, and actively supported the creation and expansion of Lawrenceville down the road. McCosh, who loved to travel, headed for the Dinky (which arrived three years before he did) on the way to Chicago, New York, Cincinnati, St. Louis, anywhere private or public school ties could be nurtured, and spread Princeton’s name, along the way enlisting alumni to join in the student search and recruiting/scholarship process, the roots of today’s Alumni Schools Committee and its global reach.

Once the students got to Princeton, McCosh and Isabella offered them in loco parentis. He came down hard on hazing and other debasing practices, crushed secret Greek societies (while allowing the first eating clubs to function openly), immediately built the new Bonner-Marquand Gymnasium to keep students busy, and supported every sport they could come up with, along with new wrinkles like the Glee Club and the Princetonian. And when they got sick, Isabella stepped in and brought her medical acumen to bear on the previously not-so-salubrious environs, personally ministering to anyone who exhibited a sniffle. The students, knowing they cared, adored them for it. The Class of 1889, graduating a year after his retirement, beseeched the college to allow McCosh to sign their diplomas.

Alumni became his strongest allies, forming dozens of alumni clubs throughout the Northeast, recruiting students, raising funds for all sorts of McCosh projects, cheering on the football team and spreading the Princeton gospel far and wide. He would hop on the train and go see them whenever he could.

The irony was that the trustees, hugely clerical, structurally old and conservative, even when faced with the reality of a university (by the standards of the day) in the early 1880s, refused McCosh’s potential crowning glory, simply to rename the place Princeton University. He constructed an intricate campaign through the alumni and students, and it made no difference. They not only turned him down, but when he did retire at 77 in 1888, they named the completely clueless and relatively conservative Francis Landey Patton to succeed him. But McCosh’s success was undeniable; while he was president, the student body doubled, and the faculty more than tripled.

Before he left, McCosh managed to get the activist alumnus Moses Taylor Pyne 1877 named to the board of trustees. Pyne, who never missed a meeting in 36 years on the board, and another McCosh student, Andrew Fleming West, created the 1896 Sesquicentennial at which McCosh’s Princeton University was formally declared and took its place on the world stage, regrettably two years after McCosh’s death. His students would dominate the institution until the retirement of President John Grier Hibben 1882 *1893 in 1933, firmly cementing McCosh as the intellectual spirit of the modern University.When you enter Hibben’s great Chapel, there are two things you should notice. The first, in the Marquand transept, is the striking Augustus Saint-Gaudens relief sculpture of McCosh in the pulpit, a tribute from his students in the Class of 1879. The second is the two rear-most stained-glass windows in the clerestory (top) of the nave: They are the window of creation on the north, and the complementary window of science on the south. In the words of the peripatetic McCosh, “It’s me collidge. I made it.”