“For over a thousand years, Roman conquerors returning from the wars enjoyed the honor of a triumph - a tumultuous parade… The conqueror rode in a triumphal chariot, the dazed prisoners walking in chains before him... A slave stood behind the conqueror, holding a golden crown, and whispering in his ear a warning: that all glory is fleeting.”

- Final lines, Patton

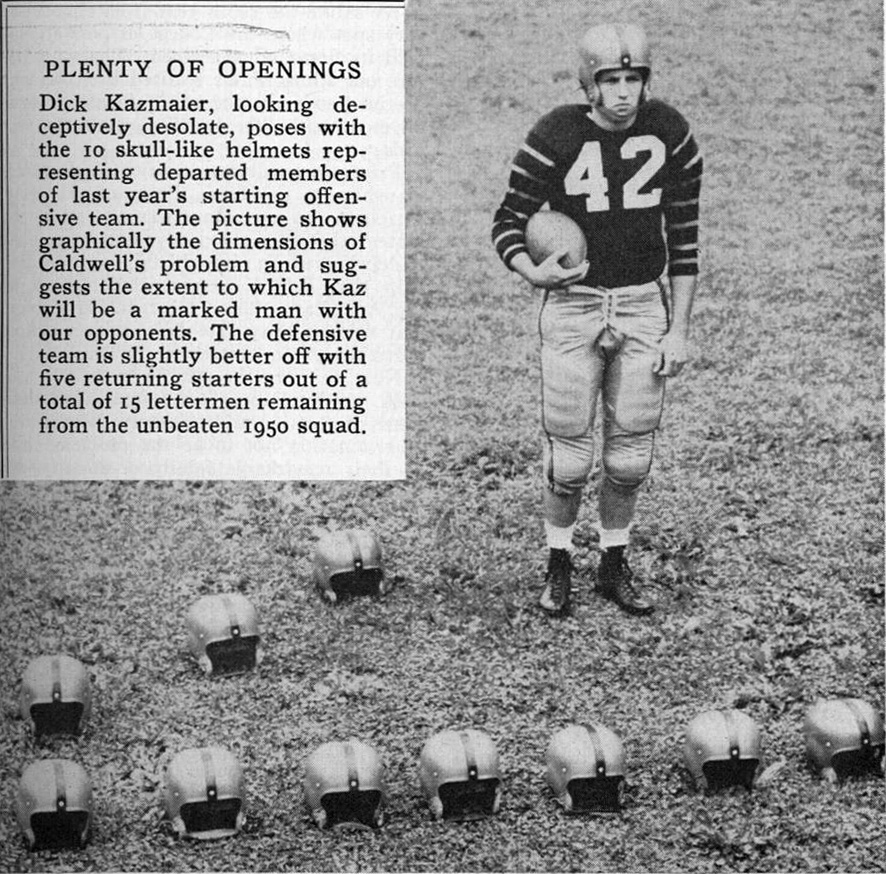

Ho-hum, another Nobel Prize. Of course, no disrespect whatsoever to Professor Christopher Sims and his friend Thomas Sargent (somehow, it’s a comfort that you can win a Nobel with a buddy) and their much-deserved economics award, but 19 Tigers of one stripe or another have won in the last 25 years, and by now it’s more surprising when the University PR machine is not cranked up to have the obligatory October press conference and champagne toast than when it is. ’Twas not always thus, of course: On Dec. 10, 1951, precisely 60 years before Sims’ and Sargent’s ceremony, Edwin McMillan *33 (in chemistry) was only the fifth Princetonian ever to receive one. It was, however, a clear harbinger of many things to come as the University beefed up its graduate and research programs (read: money). One day later, in an atmosphere of equal hoopla – but differing attire – Dick Kazmaier ’52 was awarded the Heisman Trophy at the Downtown Athletic Club in New York. In stark contrast to Stockholm, everything surrounding the occasion suggested that Princeton’s Heisman involvement in the future would be unlikely; that would be assured three years later when the Ivy League was formalized and left behind the business of athletic scholarships, or servitude, or whatever it is.

But my oh my, as any remaining semblance of amateur big-time college football went down for the last time, Dick Kazmaier (the “Maumee Menace” in the Prince’s overheated coverage) gave it a classy sendoff.

After a huge chunk of the best Princeton team in postwar history graduated in the Class of ’51, Kazmaier had been left as the only returning offensive starter. Charlie Caldwell ’25, the head coach who had turned the single-wing offense into an intricate art form, responded counterintuitively and stacked the defense, figuring the raw talent on the offensive side would round into shape before the key late-season games. [This strategy would be repeated by his protégé Dick Colman in 1964.] Penn was loaded in early October at Franklin Field, but Kazmaier’s legerdemain eked out enough offense for a 13-7 win to go 3-0; then the offense gelled. The next game against undefeated Cornell was arguably Kazmaier’s best ever. He played tailback, which you now see again in the Wildcat offenses in the NFL, essentially a back who can run or throw equally well, and on many plays has the option to do either. In this case his choices were superb: He ran 18 times for 124 yards, seven yards per pop, and was 15 for 17 passing for 236 yards, 14 per attempt. In all, he averaged more than 10 yards every time he touched the ball. A good Big Red team ended up destroyed, 53-15. Brown played better against the Tigers than anyone else all season but couldn’t solve the stacked defense (12-0); then Harvard and Yale, both having mediocre seasons, got clocked 54-13 and 27-0. Yale lost to Princeton for a humiliating fifth straight time and gained but 123 yards in the entire game; Kazmaier alone had 237. The Tigers’ fifth-straight bonfire was stoked with one game remaining. Dartmouth, having lost the frustrating hurricane game in Palmer Stadium to Kazmaier the preceding year, and wrapping up a mediocre season, decided to play smashmouth instead of football. Multiple players on both teams were hurt, Kazmaier went out in the first half with a concussion and a broken nose, but the defense pitched its third shutout in four games, 13-0. Princeton finished the career of No. 42 with 22 straight wins, and his Cornell game had been written up all across the country. Crucially, it even earned him a spot on Time’s cover, and combined with the final No. 6 national ranking of the undefeated Tigers and his career stats – 60 percent pass completions, 161 yards of total offense per game, national total-offense leader his senior year (he did the punting for good measure) – he received as many Heisman Trophy votes as the next six candidates combined, winning every section of the country, a rarity in those days. After being named the Associated Press male athlete of the year, he led the East team to a 15-14 win in the all-star Shrine Game.

This was a feel-good story – academic scholarship winner from Ohio goes to class (he graduated with honors), masters intricate offense, wins big-time football awards, is kind to small animals – sorely needed by the college athletic establishment, which was facing a PR fiasco, not for the first time, not for the last. As early as 1929 the Carnegie Foundation formed its first commission to study college athletics after a slush-fund scandal at Iowa, finding that more than 100 of the 130 colleges studied were dirty to some degree. The University of Chicago, earlier one of football’s seminal programs under Amos Alonso Stagg, dumped the game completely in the 1930s (shortly after its Jay Berwanger won the 1935 Heisman), finding even life in the Big Ten, probably the best-policed conference, was antithetical to its academic pursuits. The Saturday Evening Post exposed vast alumni malfeasance in recruiting, including cars, vacations, wardrobes, and expense accounts (during the Depression, yet). The NCAA took its first shot at regulation in 1939, but didn’t have any enforcement money.

World War II suspended most problems along with everything else (although Army’s unfair advantage of four-year deferments instantly and glaringly created the strongest program in the country). The soon-to-be-Ivies were ready with their own approach afterward, though: In November 1945 the eight presidents issued new rules eliminating athletic payments of all sorts, postseason games, long trips, and freshman eligibility, and requiring that players be students in good standing. Elsewhere attendance exploded (crowds of 70,000 to 100,000 showed up frequently) with shady finances alongside; stars were rumored to be getting $10,000 per year, many times the amount of tuition. The NCAA to save face adopted the so-called Sanity Code in 1948, outlawing such practices as the Southeastern Conference’s straight-out athletic scholarships, driving recruiting and payment abuses underground, but still posing no real enforcement threat; the whole idea imploded in 1951. Just prior to Kazmaier’s senior season, the presidents of Harvard, Princeton, and Yale felt compelled to state jointly that none were giving athletic scholarships, and furthermore that “the athletic program exists for the contribution it can make to healthy educational experience, not for the glorification of the individual or the prestige or profit of the college.” They were whistling in the wind, or perhaps a hurricane. All hell finally had broke loose, with 1951 academic scandals at William & Mary and at Army (the coach’s son was expelled), along with, for good measure gambling and point-shaving basketball scandals at powers CCNY, NYU, and LIU. Time magazine dutifully had reported all of these (as it did Dartmouth’s dirty play in the Princeton game), and perhaps its Kazmaier cover was a wistful attempt to stem the tide.

He certainly did his part to help. Demurring from pro football offers – the last Heisman winner to do so – on the common-sense basis that his admission to Harvard Business School had more potential, Kazmaier went on to a successful financial career, a Princeton trusteeship, the National Football Foundation’s Distinguished American Award, and sponsorship of the Patty Kazmaier ’86 Award, the Heisman trophy of college women’s hockey that was named for his late daughter.

But the tide was headed the other way. On Jan. 1, 1952, NBC televised the Rose Bowl live nationally, introducing the TV monster that would come to dominate the sport. In 1953, Bud Wilkinson began his record 47-game winning streak at Oklahoma (and in doing so got his own TV show), changing expectations in his now-“profession.” Oklahoma president George Lynn Cross previously had pitched his state legislature by saying, “I would like to build a University of which the football team could be proud.” By 1954 the eight Ivy presidents had seen enough; they buried their internal differences, banished the again-common athletic scholarships forever, formed a round-robin league of their own, and tacitly kissed big-time football goodbye, along with future Heismans and national championships, of which Princeton’s in 1950 became the last.

When you see the corrupt mess that the NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision inevitably has become – today even the fallout that’s legal, like the current conference realignment fiasco, is often an embarrassment – the Ivy presidents’ early decision to go the other way appears a sage move. (This is not to give them a blanket pass: The residual prohibition of Ivy participation in the Football Championship Subdivision football playoffs, for example, is insipid.) Big-time college football today has little to do with colleges and nothing to do with student athletics; it has to do with money and power and infinite ego. After Kazmaier, just two college players ever made the cover of Time, the last Roger Staubach in 1963; only pictures of high-paid coaches (and well-earned reader cynicism) followed. Princeton is much better off keeping its eyes on the prize, an ethos conveniently embodied in the retired number 42 of Kazmaier and Sullivan Award-winner Bill Bradley ’65, who at home in Missouri first heard about Princeton from Kazmaier’s exploits at Palmer Stadium in 1950 and 1951.

Of course, that doesn’t mean there isn’t a little twinge of longing every time you see the 1951 cover of Time, with the same home jersey the Tigers wear today, showing an actual student-athlete triumphant in some alternate universe. Not ever seeing No. 42 on a Princeton athlete again, however meaningful the gesture, is a mixed blessing for college sports – or what remains of it, which perhaps more appropriately falls into the province of our Nobel-winning economists.

1 Response

Kent Young ’50

10 Years AgoPride in Princeton athletics

Gregg Lange ’70’s column at PAW Online about Princeton football (Rally ’Round the Cannon, posted with the Dec. 14 issue) helped me a lot. As an undergraduate I idolized Dick Kazmaier ’52, George Sella ’50, and many remarkable football players. Having been at the Princeton-Dartmouth game in a snowstorm in 1935 when the 12th man from the end-zone bleachers tried to help Dartmouth, at the Penn-Princeton game in Philly when the mounted police tried to discourage Princetonians from taking down the goalposts after a field-goal victory over heavily favored Penn, at the Rutgers-Princeton game celebrating 100 years of football competition, and countless other games in all kinds of weather, I feel close to Princeton football.

I am sure the Ivy League made the right decision, but have wondered if it should make some adjustments such as allowing the Ivy League champion the option of competing in subdivision championships. Should Rutgers and Princeton play every five to 10 years to remind the nation where the game started? I wondered why the stadium was rebuilt on such a grand scale when the football program was designed to encourage low attendance.

I suspect, for practical reasons, little change in the Ivy League approach to athletics is warranted. Considering the overall athletics program at Princeton, we have much to be proud of. At least, I should resolve to attend some games next fall to cheer for a team who plays for the game’s sake and the University — knowing that in the years ahead, it will be more competitive within the league.