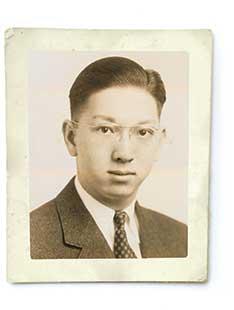

Seventy-seven years ago this month, the U.S. government began transporting U.S. citizens and residents of Japanese ethnicity to internment camps in the country’s interior. By then, Kentaro Ikeda ’44, a native of Kanazawa, Japan, and the only Japanese student on Princeton’s campus, had been identified by the government as an “alien enemy.” Spared the internment camps, Ikeda nonetheless found himself in a difficult situation: He was interned on Princeton’s campus, forbidden to move beyond a specified 5-mile radius or to contact his friends and family back home, not allowed to own a camera or shortwave radio, and subject to supervision by a faculty sponsor, with his bank accounts frozen. He spent the war in a gilded cage, wandering the campus but unable to leave it.

Ikeda was one of about 4,000 college-age people of Japanese heritage in the United States who were able to live outside of internment camps, on parole. He was not a newcomer to the United States. His father, a tea importer who reportedly introduced green tea to this country, had sent the teenage Ikeda to the Lawrenceville School down the road from Princeton, having determined that he wanted his son to receive a Western education. But Ikeda was, in some ways, a perpetual outsider. It could not have been an easy existence.

Anxieties and suspicions about spy activity pervaded the campus. In May 1940, both The Daily Princetonian and the Princeton Herald, a weekly community newspaper, reported that rumors were flying about “Fifth Columnists” on campus. Said the Princetonian: “Wild tales have spread over the Campus — tales concerning: the arrest of anarchists who plot the destruction of Palmer Stadium, of spies who hope to gain secret intelligence from the Department of Military Science and Tactics, of foreign agents posing as servants in faculty homes and as professors in university classrooms.”

An especially wild variant of these rumors, which were of course false, identified a spy cell in the household staff of Robert K. Root, the dean of the faculty. The Prince continued: “According to the report, meetings of black-bearded espionage agents were held in the basement of Dean Root’s house every Sunday afternoon and Thursday night. The proctorial staff, always on the alert, were quick to inform the dean of his problem. Root faced the crisis with equanimity, certain of the fact that his ‘cellar is too small to conceal even a small meeting.’” With all that in the news, Princeton students gave Ikeda the nickname “Fifth Column.”

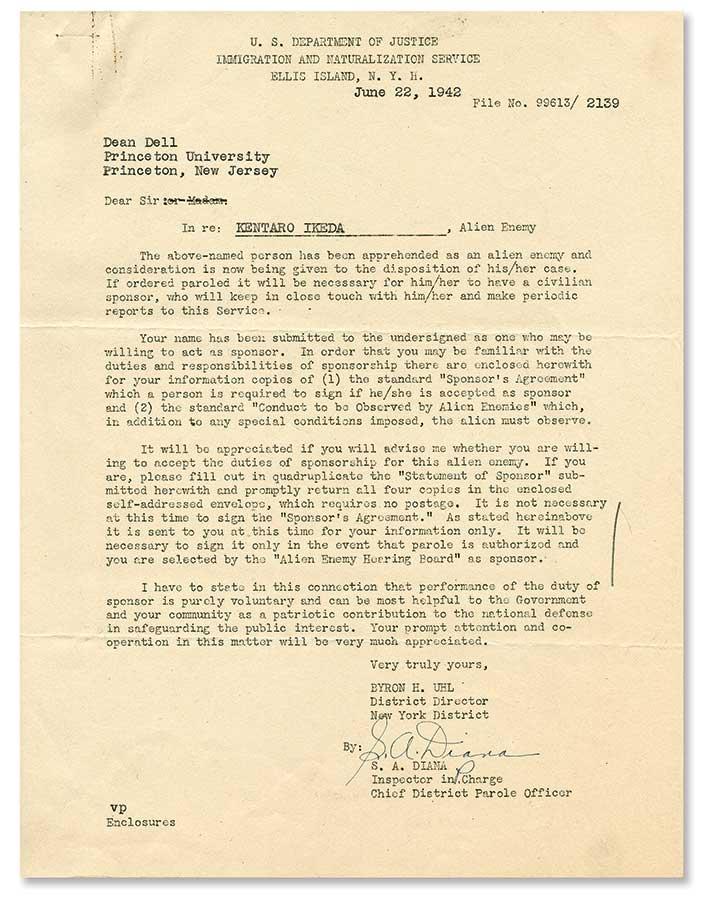

With Ikeda’s financial accounts frozen, it was necessary for the University to assume financial responsibility for him. In order to acquire even the short leash he had on campus, he had to undergo a tribunal hearing — and he required a sponsor to vouch for him and monitor his activities.

As Mudd Library Special Collections Assistant April C. Armstrong reported in an article about Ikeda on the library’s blog, Ikeda found a sponsor in Dean Burnham Dell 1912 *33, who was then dean of freshmen. Dell, who had trained as a minister and served as an Army chaplain in World War I, taught economics at Princeton before moving into administration as assistant dean of the College and then as dean of freshmen. (Upon his death, the Princeton Herald remarked, “Burnham Dell was a minister, a teacher and an administrator, but most of all he was the kind of man upon whom other men could rely, and an ever-responsive guide, philosopher and friend.”)

Ikeda sometimes asked people to call him “Ken Ikeda” or “Ken Ike.” In his senior thesis — on the economy of Japan — he described both the difficulty of obtaining good data on an opposing nation in wartime and the necessity of learning about other nations in order to cultivate peace: “A man does not hate others, if he actually understands them. Friendly relations among nations can only be obtained through understanding, and the complete understanding among nations can only be attained by knowing each other, knowing each other’s psychology, economic life, historical background and societal structure. ... Not at all, is it my purpose of this paper to contrive any justification for the war, but to analyze the radix in which the rudiments of wars are rooted.”

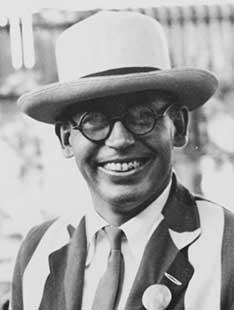

Ikeda’s closest friendship on campus was with his classmate Richard Eu ’44, a native of Singapore who had gone to Princeton to avoid the war in Europe. The two met as freshmen in 1940 and soon became inseparable, eating meals together, roaming the campus outside of class, and taking adjoining rooms in Lockhart Hall. “The war between China and Japan was going on in 1940, but we didn’t think about being enemies,” Eu says. “Maybe we stayed together because we were the only Asians in the student body.”

In any event, the two discussed the Sino-Japanese war only rarely, and only within the sort of bull session familiar to any student who has stayed up into the wee hours talking about big ideas with friends. “When we talked about the war,” Eu recalls, “he tried to justify Japan’s position, and I didn’t agree with him and tried to justify China’s position. But we didn’t know enough to make good arguments. It was just an opportunity to argue with each other.”

One anecdote Eu loved to recount in later years concerned Ikeda’s trick to win the day during the cane spree, the annual tradition in which the freshman and sophomore classes wrestled in a field for ownership of hard, flesh-bruising wooden canes. On their freshman outing, Ikeda, who practiced judo, brought out judo uniforms for himself and Eu to wear. The gambit was a success: The sophomores avoided the two Asian students dressed as though they knew martial arts. “I stuck to Ken and so I was unscathed,” Eu said in a Princeton oral-history interview in 2014.

The unlikely friendship made a small splash in the news media. In March 1942, the Trenton Evening Times ran a piece about Eu and Ikeda under the headline, “Sino-Jap Alliance Formed at Princeton.” Time magazine grabbed the story for its “Milestones” column. That same year, a student columnist for PAW, S.A. Schreiner Jr. ’42, reported that the friends were bickering for eating clubs together. (They were accepted into Key and Seal.) Schreiner suggested that the occasion showed the value of study abroad for the promotion of international understanding: “The other night a friend of ours — a physicist — seriously suggested sending students abroad to study as a final cure for war. ... We aren’t laughing now, though, for we discovered that one of the iron-bound groups for sophomores consists of a Japanese and a Chinese, both of whose fathers are involved in their country’s respective war effort. We wonder whether there would be war today if Hitler had been educated abroad — in Oxford, say.”

Even for a student who had developed collegial relations with his advisers and classmates, hostility toward Japan would have been impossible to avoid in Princeton during wartime. Eight days after Pearl Harbor, President Harold Dodds *1914 announced, at a meeting of the full student body, the adoption of a Wartime Accelerated Program that would allow any student to graduate in three years, the faster to enter military service. Ikeda entered the accelerated program, together with some 70 percent of his classmates.

The science buildings acquired new restrictions and student guards who patrolled at night. In 1942, Ikeda’s parole sponsor, Dell, received an appointment as “chief warden to organize and direct the air-raid defense program on the campus,” PAW reported. Every aspect of student life aimed at smoothing the path from campus to combat. A new, mandatory athletic program sought to train students for battle. (For example, students learned to swim for 25 yards underwater, the usual radius of burning oil when a ship was hit.) Combative sports changed their training objectives to emphasize preparing students for fights in which, in the phrase of the school’s announcement, “no holds or punches are illegal.” Each year, about half of the class graduated directly into active military service.

The University also added to the curriculum 26 new “emergency courses” that dealt with subjects of value to the war effort. These included aerodynamics, Chinese civilization, electronics, navigation, mapping, military accounting, military law, ordnance and gunnery, photogrammetry, and photography. They also included foreign languages such as Arabic, Japanese, and Russian. The Japanese language had been part of the University’s curriculum since the historian Robert K. Reischauer, who had lived in Japan for two decades, began to teach it in 1936. But it had never been a popular subject, and the war made aptitude in the language a highly valued skill. Ikeda had a native speaker’s aptitude for Japanese, but he nonetheless took courses in the Japanese language, perhaps with an eye to becoming an instructor in the subject later.

In a 1941 article about an emergency course on Japanese, The Daily Princetonian described the nation’s lack of available Japanese speakers in terms of crisis and noted “a definite lack of Japanese-speaking people available to the United States Intelligence Service.” The article quoted an assistant professor of Chinese at Yale, George A. Kennedy, who “estimated that, other than the people of Japanese parentage and missionaries who have come back from the Far East, there are no more than 50 people in the country who are capable of speaking and understanding the Japanese language to any point of perfection.” Still, within a few years, more than 120,000 people of Japanese heritage — about 60 percent of them American citizens — would be interned in camps, mainly on the West Coast and in the interior, separated from the life and work of the nation by armed guards and barbed wire.

Local publications reported that Princeton residents refused to purchase Japanese imports of any kind. Speakers visited campus to relate their experiences in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps, and news circulated of Princeton alumni taken captive by the Japanese, starting with Lt. Cmdr. Elmer Greey 1920 in January 1942. In the Princeton Herald, regular government advertisements declared, “Remember Pearl Harbor! Buy war bonds and war stamps.” Another set of ads in the same paper, which asked readers to buy war bonds and stamps so that American businesses could benefit from lower taxes, declared, above an image of soldiers in a jungle, “They are Hunting JAPS Now. Soon They’ll be Hunting JOBS.” Starting in 1942, the “faculty song,” which Princeton students used to poke fun at their professors, also began to include anti-Japanese sentiment. For example, the verse for Col. John May McDowell, an instructor in the new Department of Military Science, ran: “McDowell is a fighting man. He’d knock the Japs right off Bataan. But if he weighed just one pound more, He couldn’t get on Corregidor.”

Ikeda’s widow, Yoko, a writer and textile historian known professionally as Young Yang Chung, describes Ikeda’s reminiscences of Princeton as happy, though troubled with moments of loneliness and worry. Ikeda had told her that just after the United States entered the war, FBI agents showed up and searched his dorm room. “He was very unhappy and scared. People were coming in almost everywhere, searching through every drawer, every book, even looking in between the pages,” she says. “But he was impressed that, when they left, they put back everything as they had found it. He appreciated their professionalism. He had no hard feelings, he told me.”

The holidays, when the campus was empty, were a time of loneliness for Ikeda, she says: “Everybody left school, and he was alone.” A University administrator invited him to his home for meals during holidays, which Ikeda later recalled with gratitude. He poured some of his spare time into a monumental senior thesis, 240 pages plus bibliography and diagrams; he later told his wife that he did so much work because there was “nothing to do” in Princeton.

Ikeda was occasionally called a “Jap,” Yoko Ikeda says, but he thought it was an innocent colloquialism. And despite the political climate, he found on campus many people who went out of their way to show him kindness, his widow says. “He was a little bit shy — well, not shy, intimidated to go forward with people. He was content with being alone a lot of the time, or with spending time with Dick [Eu]. When the war came, he made friends, so many friends ... because everyone came to him to comfort him. Some friends brought food, some friends brought books. He always said later that he made more friends during the war than at any other time.”

“Until he died, he was so grateful to Princeton University because he was protected by the University, so he avoided going to the camps,” she adds. “He was forever telling me about the kind attitude toward him.”

Ikeda left Princeton in 1943 to teach Japanese at the Yale Language School. He submitted his senior thesis (“Economic Life in Japan,” dedicated to his father, though they had not spoken since the war began) in 1944 and graduated as part of that class. After the war ended, the U.S. government offered Ikeda passage back to Japan as part of a program that traded Japanese citizens in the United States for captured Americans in Japan. Ikeda turned it down. “I guess he was considered a traitor because he didn’t want to go back to his country,” Eu said later.

Ikeda remained at Yale for nine years, teaching language classes to undergraduates, missionaries, and American military personnel. Eventually, he joined his father’s tea-importing business in New York City, traveling the world on the company’s behalf. Eu, meanwhile, returned to China in 1946, on the first civilian ship that would give him passage. The two friends attended Reunions together several times over the years: Ikeda would pick up Eu at the Princeton Club in New York City and drive him back to Old Nassau, where they would spend several days at the celebration.

One day in 1996, Ikeda sent Eu a cable from New York to ask whether Eu could host his daughter, who was planning to visit Singapore on a business trip. “So I said, I have, at that time, three sons, two already married and my third son, the youngest son, was still single, so I got him to help me look after her,” Eu later said. “And before you know it, after 15 months they fell in love and got married.” What a pleasant surprise! The union of Eu’s son and Ikeda’s daughter laid the capstone in a lifelong friendship. Ikeda died at the age of 92 in Larchmont, N.Y., in 2011, survived by Yoko, three children, and two grandchildren.

Last June, the Supreme Court determined that the internment of Japanese American citizens during World War II had been unconstitutional. In so doing, the court overturned the decision in Korematsu v. United States, the 1944 case in which the Supreme Court upheld the military orders that resulted in the internment of Japanese Americans.

The support that Ikeda received to complete an education at Princeton during the war was highly unusual. For many young people of Japanese heritage, internment marked a forced end to their higher education. Even before their relocation to military camps, the government’s 5-mile travel restriction forced many students to withdraw from their colleges. The freezing of their families’ bank accounts placed yet another obstacle before their education. Many students dropped out of school in order to stay with family members, or with the aim of making sure their families were safe before they returned to their studies, or simply out of despair over their situation, as the historian Allan Austin notes. “The anxiety over the future and the fear and despair they face at home,” an analyst wrote in a field report on young people in internment camps, “makes it impossible for them to study.”

Several volunteer organizations, such as the Quaker-run National Japanese American Student Relocation Council, worked to help young people leave internment camps to attend college — a task that, as Austin says, required financial aid due to frozen funds; “community acceptance expressed in a letter from a local public official; and clearance of the college in question by the War Department and the Navy.” Still, the War Relocation Authority, the government body charged with moving and monitoring people of Japanese ancestry, took a long time to clear Princeton for the matriculation of interned students who applied to attend, perhaps because the government was reluctant to permit young people from internment camps to attend schools that had classified research programs, as Princeton did. More representative than Ikeda’s parole on the campus of a great research university were the Commencement exercises of June 1942 at the Santa Anita Assembly Center, where some 250 students received diplomas from the junior high schools, high schools, junior colleges, and colleges from which they had been removed. The speaker congratulated the young people “for receiving their diplomas under such trying circumstances” and encouraged them to apply their “education for the building of a better world.”

The internment of Japanese Americans had far-reaching legacies in both U.S. law and the lives of people of Japanese heritage in the United States. Shame and silence, mistrust and misgivings, belonged to the experience even of those whose faith in opportunity and fair treatment was greatest. Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu, the civil-rights activist at the center of Korematsu v. United States, felt humiliated by his experience and, in later years, refused to discuss it; his daughter, Karen, learned about his role in the Supreme Court case when her friend was researching a high-school project, notes Denny Chin ’75, a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals who teaches on issues relating to Asian Americans and the law.

For his part, Ikeda’s best friend at Princeton, Richard Eu, says he was not aware that Ikeda was not permitted to travel beyond five miles from campus. “I didn’t know about that,” he says. “I don’t think he ever mentioned it to me.”

Elyse Graham ’07 is writing a book about the wartime flight of mathematicians from Europe.