There are a few facts about immigration that Douglas Massey *78, professor of sociology and public affairs, wishes every American knew. First: For 11 years, more undocumented residents have been leaving the United States than entering it.

Second: Most undocumented immigrants cross into the country legally, with a visa, and then overstay — in fact, apprehensions at the border are at a 40-year low.

But over a four-decade career researching immigration, Massey noticed that facts like these have little bearing on the public conversation. “There’s so much disinformation and misinformation in public circles,” he says.

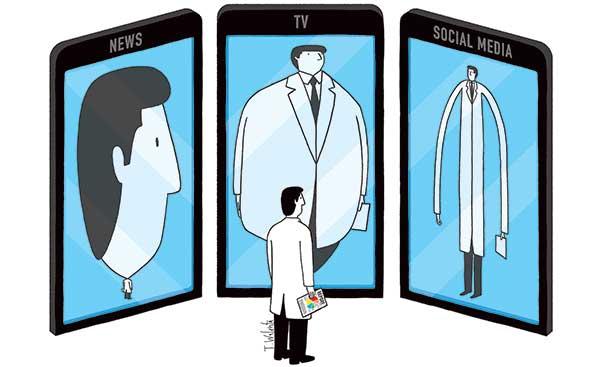

This is why Massey and Stanford political scientist Shanto Iyengar looked into how empirical findings get distorted and suppressed until the public narrative is stripped of scientific fact. They argue that scientists risk irrelevance if they do not change how they engage the public. “The National Academy of Sciences prides itself on being nonpolitical,” Massey says. But when misinformation is politicized, “we’re forced into a political reaction to counter the falsehoods.”The pair published an article in November in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences documenting how the rise of cable TV and the repeal of the fairness doctrine in the 1980s enabled a new generation of ideologically motivated news channels — from Fox News to MSNBC — to replace mandated public-interest news broadcasts with ideologically motivated content. Ideological content flourished further as social media allowed misinformation to be shared with huge audiences. As an example from his own field, Massey points to a National Academies’ report on immigration, which was leaked before publication to Breitbart News, resulting in a story headlined: “$500 Billion Immigration Tax on Working Americans.”

Other websites and interest groups, like the Center for Immigration Studies and the Heritage Foundation, ran articles with similarly alarmist headlines, but in reality, the report had unsensational and nuanced conclusions. Immigration, it said, has the biggest negative impact on wages for previous immigrants, who hold many of the same jobs. And while state and local governments do face costs to educate the children of these immigrants, children who remain in the country will contribute more in taxes than either of their parents or the average native-born worker.

Such failures to spread the word about their results are common for “naïve” researchers, says Massey. “They think if they put together a clear press release and make a few clear interviews with NPR and The New York Times that that’s all it takes,” he says.

In reaction to these trends, last year the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine jointly announced a project to identify and counter online misinformation. Massey hopes its outcome will give scientists institutional support to fight falsehoods in ways individual scientists cannot. “Scientists all have day jobs, whereas, say, the Center for Immigration Studies has a fully paid staff whose only job is to get negative information out about immigrants and immigration,” he says. “Frankly, we’re overmatched.”