Jenni Levy ’82 is an internist in Allentown, Pa., who specializes in palliative medicine and has her own business assisting in the creation of advance directives and providing advice about end-of-life care.

There was an unmistakable thud in my parents’ bedroom. I ran to the door and knocked, but when the answer was “Go away,” I marched in.

Dad was on the floor, partially dressed, and furious. My gentle, soft-spoken father ordered me, loudly and profanely, to leave the room. I have no idea how my mother, who was half his size, got him upright, because I returned to the guest room like the obedient daughter I’d always been. In the morning we followed the family custom and pretended it hadn’t happened.

It was no surprise. Dad hadn’t been able to walk well for a couple of years by that time, but he and Mom had remained in the four-story house of my childhood. My brother and I had decided to talk to him — but not that weekend. It was Dad’s 70th birthday, and we didn’t want to upset him.

Dad brought it up. “Mom wants me to talk to you about last night,” he said, after the birthday dinner. “I’m fine.”

“You sent me to medical school. I paid attention,” I said. “You are not fine.”

I talked about safety and making things easier on my mother. He said I was overreacting, and he’d been a doctor longer than I had, anyway. After 20 minutes, he said, “I hear you,” and that was that. My parents did not move.

As a palliative-care physician, I’ve worked with scores of families in the same situation I struggled with. I’ve learned that no matter how much you know — and how well-meaning you are — helping your parents as they age is a struggle. We do what we can so that we can live with ourselves. I can’t make it easy, but I can share my answers to some of the concerns I hear most often.

How can I get my mother to sell that house and move somewhere more manageable? The short answer is: You can’t. If Mom is still capable of making her decisions, then you have nothing to say about it. You can offer, suggest, and support — but you can’t control her. We want our parents to be safe; they want to be independent. You may have influence if you can help her feel that you respect her choices and appreciate her point of view. If she doesn’t feel judged, she’s more likely to listen to you.

Start by asking questions and really listening to the answers. Try to understand why she wants to stay in the house — what does it mean to her? What is she concerned about if she moves? Instead of responding with counterarguments, reflect back what you hear: “You’ve lived in this house a long time, and it holds a lot of memories. It also sounds like you’re worried you’ll run out of money if you have to move.” Look for ways to make the house safer — if you’re concerned about the stairs, can you rearrange things so she doesn’t have to go up and down? Can you put in a stair lift? A home-safety assessment from physical and occupational therapists may provide options.

Be clear about your own limits. As difficult as it is to say “no,” it’s necessary. If your parents are unrealistic about their abilities, that doesn’t mean you have to agree with them or support them.

We do what we can so that we can live with ourselves. I can’t make it easy, but I can share my answers to some of the concerns I hear most often.

How do I know if Mom is capable of making her own decisions? And what do I do if she’s not? Dementia is not inevitable. Most of us notice some decline in our mental abilities, but when that decline interferes with our ability to function, that’s not normal. If you’re concerned about your parent’s memory, talk to the doctor. Privacy laws may prevent the doctor from sharing information with you, but they don’t prevent you from sharing information with the doctor. This is best done in writing, so your concerns will be entered into the chart. If possible, go to the appointment with your parent and ask Mom or Dad to sign a form giving the doctor permission to talk to you.

Dementia isn’t the only cause of memory loss and cognitive decline. Many physical illnesses can play a role, as can alcohol, prescription medications, and over-the-counter drugs. A comprehensive geriatric evaluation can help identify these problems. Geriatric assessment programs include a social worker and often mental-health providers. They can help determine if your parents have the capacity to make their own health-care decisions. They can also identify other resources and support to help everyone involved, including families and caregivers.

What paperwork do I need if I have to make their decisions? If you must step in and make decisions for your parents, you will need to get power of attorney. This must be done before they lose capacity. The power of attorney for health care is not the same as the power of attorney for legal and financial decisions. An elder-care attorney can help you complete the appropriate paperwork, or you can find documents at fivewishes.org, which offers the health-care power-of-attorney document and a living will for a small fee and does not require an attorney. If you obtain documents online, check to make sure they are legal in your state.

If I have the health-care power of attorney, do my parents need a living will? A power-of-attorney document identifies who will make medical decisions. A living will provides guidance about what those decisions should be. Some states limit the decisions someone with power of attorney can make. Pennsylvania, for example, does not allow a health-care agent to prevent insertion of a feeding tube without written instructions from the patient, so in Pennsylvania you need both.

A living will should be more than a set of checkmarks about tubes and machines. You want to know what “quality of life” means and what tradeoffs are acceptable to get there. Does your dad want treatment that will save his life if that means he won’t be able to care for himself? It’s more complicated than saying “Do everything” or “Pull the plug.” I had this conversation with my mother shortly after she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia. She made it clear that she did not want any treatment that was going to cause suffering, even if it prolonged her life. She wanted to stay home and be comfortable, no matter what. That conversation guided the decisions my brother and I made over the last years of her life, and we had the comfort of knowing that we were doing the right thing.

I don’t think my dad should be driving any more. What do I do? Losing the ability to drive is a terrible blow, and many people continue to drive when they should not. Your dad’s doctor can make this determination (you may need to prompt the physician), report to the Department of Motor Vehicles, and deliver the bad news to Dad. Many states will honor your confidentiality if you report an unsafe driver to the DMV, and may require the driver to take a test. You may also need to remove the car or the keys if Dad decides to ignore the doctor or the DMV. That will be difficult — but not as difficult as living with the knowledge that your parent killed or injured someone when driving.

If there’s any question about your parent’s ability to drive, a Mature Driver Evaluation may settle the issue. It will check reflexes, vision, motor control, and other factors of safe driving.

How do I find a driving evaluation, an elder-care attorney, or a geriatric assessment? Every county in the United States has an Area Agency on Aging that provides support and information for elderly residents and their families. It can help you find local providers for in-home care and residential care as well as other services. Staff members also offer connections to support groups and resources to help you take care of yourself, which is essential.

My sister doesn’t think Mom needs this much help. How do I convince her? Try to focus on interests, not positions. Your position is that Mom needs in-home care; hers is that Mom doesn’t. Your interest is keeping Mom safe. What’s your sister’s interest? What is she worried about with in-home care? Ask honestly curious questions and listen to the answers. If you still can’t agree, then you need to decide if you are worried enough about Mom to take action that might damage your relationship with your sister.

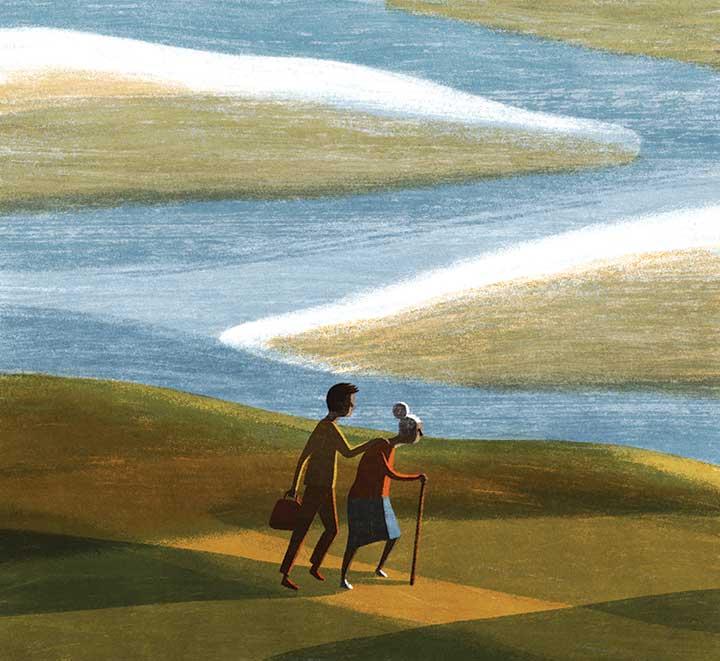

My parents stayed in their house for the rest of their lives. My father lived two more years with those four flights of stairs, and six years after he died, my brother and I had to find full-time care for my mother. That wouldn’t have been my choice for her, but it was hers for herself, and we honored it.

Our parents are lucky not to grow old alone. We’re also on the journey, and it’s not an easy one. We need to be gentle with ourselves as well as with them.