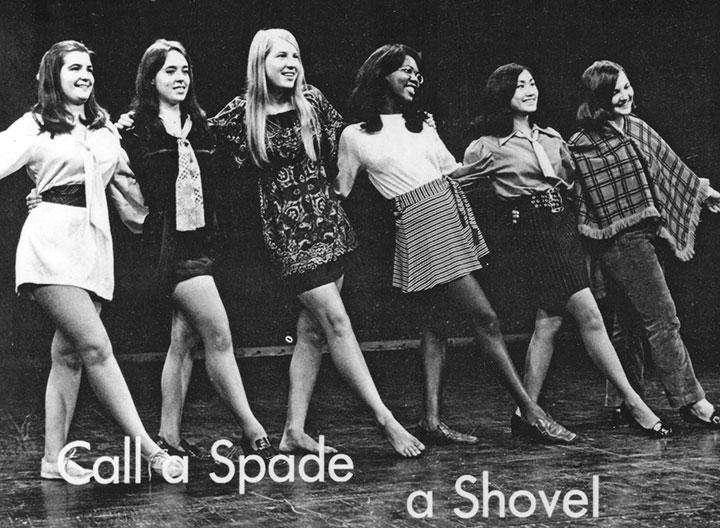

The Triangle Club’s 1969-70 production, Call A Spade A Shovel, incorporated student views of the war in Vietnam through heavy dose of political satire. That caused some problems when the group took the show on the road during the University’s holiday break. At performances in Plainfield, N.J., Wilmington, Del., and Indianapolis, audience members walked out in response to sketches like “The Prime of Miss Jean Bircher,” about a hawkish, right-wing kindergarten teacher. In Grosse Pointe, Mich., with a largely non-alumni crowd in attendance, defections reached epic proportions: Afterward, “the only ones left were Grosse Pointe’s three Democrats and a bunch of kids,” one cast member told PAW.

J. William Metzger ’71, business manager and president-elect of Triangle, revisited the tour in an essay for PAW, examining what worked, what didn’t, and what club members were considering as they looked toward the future. “[W]ith an accepted value-disjunction between many students and many alumni, the question of theatrical integrity, or ‘To what extent should we tell them what they want to hear?,’ takes on increased importance,” Metzger wrote. (Read the full essay below.)

Fifty years later, the 128-year-old troupe continues to test the boundaries of musical comedy. During intercession later this month, Triangle members will be touring with the 2019-20 show, Once Uponzi Time, in Washington, D.C., Jacksonville, Palm Beach County, Miami, and Atlanta. For more information, visit TriangleShow.com.

We Bombed in Grosse Pointe

A Survivor’s Journal of the Triangle Tour

By J. William Metzger ’71

(From PAW’s March 3, 1970, issue)

For 81 years, the Princeton Triangle Club has entertained alumni audiences from coast to coast with an original musical comedy featuring the all-male kickline. This year, however, the content of Call a Spade a Shovel proves to be so “entertaining” that it pleases thousands but drives hundreds away from those local alumni audiences and causes a wave of controversy sweeping from Grosse Pointe, Michigan, to Nassau Hall. Why?

The pre-performance article in the National Observer explains that Princeton students feel the shows must “change with the times or die.” On the other hand, several alumni write, in response to this year’s performance, that Triangle has changed and will die because of it. Alumni wonder how long the Trustees and college officials will “stand idly by, while every sacred cow of the American society is ruthlessly desecrated by a group of hippie-Communist students on stage!” And they call for “action” to be taken by “someone.” The audience reactions and the letters received emphasize the real gap between the students of Princeton’s past and present. To what extent must a show’s content satisfy the attitudes of the audience? An investigation of responses to the show may provide an answer.

We start out with Princeton audiences that respond more favorably to the show than in any other city. The hopeful expectations of the cast and staff of Triangle are satisfied by the continuous laughter of two sell-out houses among the four performances: the sharp angle of satire cuts pleasantly for both students and townspeople. Comments by the audiences after these shows reflect, however, one concern: how will the South and Midwest react to such pointed satire?

On December 12, one week after these successes on the home front, the Triangle troupe descends on Plainfield, New Jersey. This “veritable hotbed of Princetonianism” — as campus officials know it — lies nestled in the rolling hills of suburban New York City. The troupe could not anticipate that 50 alumni from an audience of less than 400 would tolerate no more than the first act sitting down. As Flip Connell, whose home is Plainfield, playing a “Target Detector Teacher” in army boot camp, is mistaken for the enemy and shot by his trainees, a lady in the first row screams, “Hooray! Get him! Kill him!”

The on-stage orchestra faces the audience each night, and witnesses the majority of walk-outs at the Westfield N.J. High School Auditorium. They find that most leave after the first scenes of the second act, all dealing with war. The first skit, “The Wonderful World of War,” was written by a Vietnam veteran, a member of the Triangle troupe. The scene, a take-off on the TV coverage of sporting events, complete with commercial breaks and live war action “on the field,” seems to hit Plainfield the hardest of any. The final segment of the skit is an “instant replay” in which a mother watches her son “riddled with enemy machine-gun bullets” on TV, right at home in Secaucus, N.J. Immediately following this Act II opener is a song, “D-Day is Over,” claiming that old values of war heroism are dead today. Third in this political series is “Miss Jean Bircher’’ a kindergarten teacher, played by Scott Berg, who explains to her class how America is winning the war: the Vietnamese have killed only 40,000 Americans, while we have killed 70,000 of those “dirty, slant-eyed Commie chinks. That’s 30,000 more, class, which is almost a million!” By this time, about 100 have left the performance, and those remaining find it increasingly difficult to laugh or applaud. The 3-hour 20-minute show plods endlessly until the finale, at 11:45 p.m.

Only a third of the invited guests decide to come to the after-party. One catches fragments of conversation like: “I hated it” or “the girls are wonderful” or “if you could only get rid of those girls.” We learn that, contrary to general expectation, a person’s attitude toward the show is not primarily a function of his age. The two alumni who argue most vociferously against the show both graduated from Princeton in the late ’50s. We meet as many of the Old Guard who like the show as we do young junior executives who are appalled by it.

The administration receives more letters after the Plainfield performance than after any other. Apparently, as most of the alumni are commuters to the Big City, the interests of this social class are antithetical to the values expressed in the show; certainly, the jabs at Nixon, the War, institutionalized religious beliefs, and the political “heroes” of the silent majority, are not what the Plainfield audience expects.

The next night in Wilmington, Delaware, a smaller audience does not respond as vocally, but feels as strongly about the content of that “Communist display.” An alumni host explains after the show, “Most people in Wilmington depend on the opposite attitudes to keep their jobs … We never expected anything like this.” I am surprised that only 50 in an audience of 300 tuxedoed gentry choose to leave. Only a handful of alumni, all local sponsors of the show, attend the after-party at the Wilmington Country Club.

On Tuesday, December 16, the 1,100-seat capacity crowd at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall generates tremendous excitement for the show. As a break from tradition, Triangle’s officers have drastically lowered the ticket prices of the New York performance, so that the majority of the patrons are younger, non-affluent (or pre-affluent) Princetonians. The New York Times feature story of Dec. 5 assures the sell-out house, and the box office reports that at least 25% of the tickets have been sold to a non-Princeton, general public. They applaud the obvious as well as the subtle lines. The rapport with the amateurs on stage makes New York the highlight of all tour performances.

The actual traveling tour begins with the Dec. 17 performance in Washington, D.C. Forewarned about the content of and “projected reactions” to the show, the Washington alumni hosts have given away a number of tickets to high school and college students in the area. This proves to be a tour “truism”: if a significant number of students are present, the laughter is stronger and the cast becomes more enthused; this enthusiasm makes the show move more quickly. Thus, with students acting as catalysts, the show turns into a rapid “Laugh-In” format; the audience has less time to let the devastation of values sink in, and so responds with an immediate reaction of laughter. The quickened pace also tends to obscure “dead” lines and to emphasize the good “punch” lines. One has to concentrate on the next line before thinking about the last one.

Although the social classes represented are no different from Plainfield or Wilmington, no more than ten walk out. The cosmopolitan atmosphere of Washington (much like New York), in addition to the consciousness of political affairs in the nation’s Capital, joins with the large student group to create a pleasant performance.

The tremendous applause to the “Nixon Press Conference” is unequalled for the rest of the tour. Nick Hammond, as Richard Nixon, answers a number of questions with the now-famous cliché: “I’d just like to make one thing very clear. In these troubled times, I think it is crucial to consider all the factors involved. Of course, much of this information is classified and cannot be discussed in an open press conference.” For the final question, he turns on a tape recorder which repeats the same oration, as he walks back to his living-room to watch a ball game; at this, the crowd goes wild.

At 7 a.m. on the 18th, the tired troupe begins a 16-hour bus ride into the deep South. Picking up the cue from Washington, we spend the day of travel cutting many of the proven un-funny lines, thus trimming about 20 minutes of excess fat from the 3½ hour show. By rearranging the running order of the skits so that all the political messages are not delivered at once, and by encouraging the cast to quicken the pace, we feel ready for Jacksonville, New Orleans, and Houston. Everyone warns us and worries about the expected reaction in the South; we have a real fear for our performing lives.

But it works. In all three cities, we find a surprisingly favorable response from audiences that fortunately include many students. The show moves quickly, and the audiences seem to work as hard to appreciate our message as we do to present it.

Fortunately, the audiences are primarily composed of alumni and their friends. They have experienced at least four years in the North at Princeton, and, as alumni, feel a responsibility to receive our satire with relatively open minds. Whether their enthusiasm is an over-reaction is uncertain; but few substantiate our fears of a massive exit from the theatres.

And off-stage, the troupe enjoys the pleasant surprises of Southern hospitality. Throughout these shows, though people complain at the after-parties of the predominance of war and political skits (and justly so), the troupe could not have been received and appreciated more cordially. These three cities turn out to be a geographical anomaly.

Oftentimes, an alumni association cannot afford to bear the tremendous cost of a Triangle visit entirely without assistance. In Denver, our sponsorship is shared by the State of Israel Bonds, an active Jewish organization that raises funds for the cause of the war in their homeland. With more effective publicity and committee work, this group assists the alumni (actually, just the opposite direction) to make Denver a financial success.

However, knowing that an alumni association has a supposedly greater inclination and sensitivity to Triangle (which held true in the South), and remembering the Plainfield responses to the religious material in the show, the troupe bolsters itself for the wrath of a predominantly Jewish, non-Princeton audience. As in the Southern cities we visited, Denver proves to be a young city who thinks young, and who receive the TV-type, “Laugh-In” format, with all of society’s reified icons as fair game. A small crowd can be extremely vocal; and despite the size limitations of the stage, this audience meets our topical revue with unexpected delight. At the after-party, the most popular topic of conversation is the worried alumni question, and our very pleased answer to, “How did it go down South?”

Then the next performance, Indianapolis, brings it all back home. After the show, one of the sponsors remarks, “If you think alumni are gonna keep shelling out for that stuff, you’re crazy!” It’s not such a great start to the second half of the tour.

Indianapolis, like Wilmington, is small and a fairly closed system. We feel as though we have twanged the latent vocal chords of the “silent majority.” They, in general, do not like the show.

Cleveland, the next night, reacts much the same as Indianapolis, though they are more prepared for the coeds and the political slant (since the last Indianapolis performance 7 years ago, Cleveland has sponsored us five times). A relatively quiet complaint that the show is “a little heavyhanded” is all we hear; but they add that, after five consecutive shows, it might be a “good idea to wait a while” before the next return visit.

Then our fears, up to now dissuaded, are proven with a vengeance. On December 29, the Triangle troupe arrives in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, for the next-to-last stop. During the following 24 hours, so many unexpected events happen that we cannot distinguish between what is a play and what is real life.

Housing arrangements cause an unequalled logistics problem: how to get 40 people back and forth from 12 homes, four separate times. We save the complex “Master Housing Plan Chart” that our hostess drew up, as a memorial to her spartan efforts.

The sponsoring group, as in Denver, is an amalgam of the alumni association and a civic group, the Grosse Pointe War Memorial Association. As I understand it, the citizens of the Pointes contribute to the support of the organization and, in return, are presented a variety of cultural events. Triangle is included in a series of theatrical comedies that bear the alluring title, “The Lighter Side of Life.”

The tech crew finishes setting up the show early, since the tiny stage cannot accommodate the rolling unit or scaffolding of the set. The troupe attends a “tux or tails” cocktail party at the Grosse Pointe Woods Country Club, then later dines at the War Memorial Association, while groups of audience hopefuls arrive to attend their candlelight dinner in the dining room above the theatre. By the opening curtain at 9:00, an overflow crowd of 520 eagerly awaits the “only touring college musical in the country.”

After so many performances, the orchestra members facing the audience can predict, almost immediately, the general reaction: the first “sure-fire” lines receive few, if any laughs; and a foreboding silence pervades the intimate theatre. At the beginning of “Ah! Secaucus,” a spoof on the current trend of nudity in Broadway shows, Rob Hewell as Stage Manager for the mock production enters and, facing the real audience, asks the “fake audience” of tryouts “to be quiet, and we can begin tryouts right.” One lady, upon hearing this order, stands up and screams, “No, you can’t! This show is terrible! The show is over!” The orchestra members look at each other in amazement, as one member murmurs, “Tonight, I think maybe she’s right.”

It is surprising, in a way, that 500 of the original 520 return for the second act. The modifications made before the Southern cities — rearranging war skits, quickening the pace, scratching “dead” lines — have no effect. The students in the audience sit as dazed and expressionless as their parents, not knowing how to react to a message that seems so foreign. After the “Wonderful World of War” about 40 people walk out. Without ostentation, but with great socializing effect in the small theatre, other groups join the exodus, leaving even in the middle of a scene. As the house lights go up at the end, the orchestra counts only 200 still in their seats.

At the after-party, also in the War Memorial Association complex, only the hosts join the troupe. One sponsor mentions, “If that’s the lighter side of life, I don’t think I want to see the heavier side.” As the local paper later reflects, a broken water main at the Association estate was not the only floodgate that burst that day. The non-alumni audience (clearly holding strong, vested interests in all the values we satirized on stage) have expected a non-offensive comedy, and we did not entertain them. An unhappy time was had by all.

Pittsburgh, the last stop, ends the tour as successfully as it had begun. All the improvements in the show “work,” and a standing ovation for the last finale is a tribute to the courageous efforts of this undergraduate family. It’s over.

And now the big question remains: will it go on? With the consciousness that prevails on campus, Triangle anticipates an increase in the future ranks of this changing tradition. And yet, with an accepted value-disjunction between many students and many alumni, the question of theatrical integrity, or “To what extent should we tell them what they want to hear?,” takes on increased importance.

The syndrome indicated in alumni letters (“Why don’t they do something about it?”) can perhaps catch on, as if the fear of Triangle’s impending demise becomes the cause of its death.

However, the South surprised us, as did the non-alumni sponsors in Denver. By branching out, both on stage and on tour, into the experiences of people in the world beyond Princeton, it seems that these “message” and “media” problems can be overcome: a comedy with a bite can reflect current student opinion and entertain the other generation as well.

How wide is the gap?