On the day of Commencement, other things seemed to overshadow the symbolism of opening the FitzRandolph Gate. Most of us didn’t wear caps and gowns, but all of us heard the buzz of the cicadas swarming the campus. We applauded, even cheered, the star-quality honorary-degree recipients, including Walter Lippmann, Coretta Scott King, and the clear crowd favorite, Bob Dylan, who later memorialized the event in a classic song that’s still one of my favorites, “Day of the Locusts.”

But these days, there’s another Dylan song that’s become more meaningful to me: “My Back Pages,” with its arresting refrain, “Ah, but I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now.” For four years as an undergraduate, I got a Princeton education; for the past four years as a historian, I’ve been getting a fresh education about Princeton.

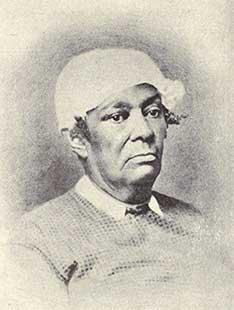

I’m writing a book about Betsey Stockton, a woman born into slavery in Princeton in 1798. She was given as a young child into the household of the Rev. Ashbel Green 1783, who later became the eighth president of the College of New Jersey (1812–1822) — and the eighth to have been a slaveholder. Green eventually emancipated her, and Betsey Stockton went on to live a remarkable life of firsts, all of them in service to people of color: the first Black person, the first former enslaved person, and the first single woman to serve as a missionary in Hawai’i; the first missionary to start a school for the common people of the islands; the first person to run an infant school for Black children in Philadelphia; the first name on the list of Black people leaving the main Presbyterian Church in Princeton to form a separate Black congregation, the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church; and the first teacher in the town’s only school for Black children. For the last three decades of her life, until her death in 1865, there was no more significant figure in Princeton’s Black community.Writing the book has led me to think more about the historical connection between the college and that community, to see the two worlds on the two sides of Nassau Street in a new light. In the antebellum era, genteel-seeming Princeton was a tough town for Black people. My research — enriched by fellow professors and students associated with the Princeton & Slavery Project (slavery.princeton.edu) — has turned up numerous examples of racism, ranging from local laws “to prevent nocturnal Riots and disorderly and tumultuous meetings of Negro and Mulatto slaves or servants” to physical attacks and threats of lynching against Black people. Many of the perpetrators of those acts came from the college, and many of those came from the South (as I did, over a century later, in 1966).

The Civil War ended slavery, but it didn’t end racism, in Princeton or anywhere else. Paul Robeson — born in Princeton in 1898, a century after Betsey Stockton — wrote about the “caste system” that surrounded the town’s Black people in his childhood: “The grade school that I attended was segregated and Negroes were not permitted in any high school,” much less any level beyond that: “No Negro students were admitted to the university.” Robeson came to a succinct conclusion: “Princeton was Jim Crow.”

And so it stayed well into the 20th century, into my time at Princeton. My main connection to the Black community came in my junior year, when I worked two mornings a week as an assistant teacher at the Trenton Street Academy, a storefront school for Black teenagers who had dropped out — or had, more likely, been pushed or kicked out — of their regular schools. But that was Trenton, not Princeton. At the time, I never got to know the people in the Black community who lived so close by, much less the history of their community. If I’d gone a few blocks from the campus along Witherspoon Street, I’d have come to the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church, where Betsey Stockton is commemorated in a stained-glass window — “Presented by the Scholars of Elizabeth Stockton” — and a brass plaque. Instead, it took me almost 50 years to find her.

Thanks to the good work of the Historical Society of Princeton and, more recently, the Witherspoon-Jackson Historical and Cultural Society, I’ve been able to pursue my continuing education about the relationship between campus and community. And one lesson in that education calls me to think again about the opening of the FitzRandolph Gate, in 1970, with the class slogan, “Together in Community.” Some of my class officers, particularly Stewart Dill McBride, may have been more aware than I was at the time about the importance of reaching out to the rest of the town, and they now deserve my belated gratitude.

I have no illusions, of course, that the symbolic unlocking of a campus gate 50 years ago could bring about racial equality or social justice. The gate itself was named for Nathaniel FitzRandolph, a major 18th-century donor but also a slaveholder: That’s a valuable reminder about Princeton’s origins and our ongoing need to reckon with the past. But even flawed symbols can serve as useful signposts to the future. As the University now embarks on a new commitment to anti-racism in its curriculum and other campus activities, the work can’t be strictly academic, but needs to connect to the local community. The walkway from Nassau Hall passes straight through the FitzRandolph Gate, crosses Nassau Street, and then becomes Witherspoon Street. That’s always been an important two-way path for Princeton, and it’s especially so now.

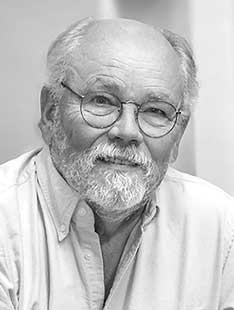

Gregory Nobles ’70 is professor emeritus of history at Georgia Tech and author of The Extraordinary Life of Betsey Stockton: An Emancipation Journey from Princeton, Around the World, and Back, which will be published by The University of Chicago Press in 2022.