Reading Room: Ilya Shapiro ’99 on the Difficulty of an Apolitical Court

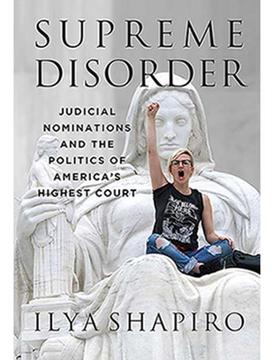

Supreme Court nominations have grown increasingly acrimonious over the last few decades and have become political issues in each of the last two presidential elections. In his latest book, Supreme Disorder: Judicial Nominations and the Politics of America’s Highest Court (Regnery Gateway), Ilya Shapiro ’99 traces the history of Supreme Court nominations, which he argues has been fraught for much longer than people generally believe. Shapiro, the director of the Robert A. Levy Center for Constitutional Studies at the Cato Institute, spoke with PAW about the nomination process and how it might be reformed.

Presidents are politicians and so are senators, so politics in one form or another has always played a role in Supreme Court nominations. Even George Washington had a Supreme Court nominee rejected. What’s different today is that, as the federal government has grown more powerful, so has the power of the highest court, and there are widely divergent theories of judicial interpretation that map onto partisan preferences at a time when the parties are more ideologically sorted than they have been since at least the Civil War.

Are the confirmation hearings also different?

The Senate didn’t hold confirmation hearings on Supreme Court nominees until 1916, when Woodrow Wilson [1879]nominated Louis Brandeis. That was a presidential election year, and Brandeis was both the first Jewish nominee and a Progressive, so his nomination was very controversial. Brandeis, however, didn’t testify; it was considered unseemly for the nominee to submit to questions about his judicial philosophy and background.

Still, confirmation hearings were often fairly short and perfunctory. When John Kennedy nominated Byron White in 1962, the whole hearing lasted about an hour and a half, and the nominee was questioned for about 15 minutes, mostly about his football career. The first fully televised hearing was Robert Bork’s in 1987, which was also the first year that C-SPAN had access to the Senate. Joe Biden, incidentally, chaired that hearing.

Where does the Senate’s refusal to hold hearings on Merrick Garland’s nomination fit into this history?

Control of the Senate is the whole ballgame in terms of Supreme Court nominations. We’ve had 30 Supreme Court vacancies arise in presidential election years. In times of divided government, when one party controls the presidency and another party controls the Senate, the nominee has only been confirmed twice in 10 attempts. In periods of united government, 18 of 20 nominees have been confirmed. So knowing nothing else, you would have expected the Garland nomination to fail in 2016 — it wasn’t the first one the Senate declined to act upon — and the Amy Coney Barrett nomination to succeed in 2020.

You propose that the Senate no longer hold confirmation hearings.

At this point they are just a spectacle. It’s largely an opportunity for senators to grandstand, so we don’t learn anything new about the nominee. The Senate could have longer closed hearings, as it does to go over things like the nominee’s FBI background check and other sensitive matters, but the public hearings now cost our public discourse more than they benefit it.

Some have proposed expanding the size of the court. Is that a good idea?

Nothing in the Constitution specifies the size of the Supreme Court. Historically, it has gone from six members, down to five, and up briefly to 10 before Congress settled on nine in 1869. But each time the size of the court changed, there was politics involved. It’s hard to see how expanding the court now would remedy whatever ails our judicial process — any more than FDR’s failed court-packing scheme did in 1937.

In the abstract, you might want a larger court because each seat would be worth less, so nomination fights might be less contentious. Maybe there should be one justice per appellate circuit, as it was in the early days, which would expand the court to 13 seats, but it’s hard to see how you get there in a politically neutral process that preserves the court’s independence. Others have proposed term limits for justices, but that would require a constitutional amendment.

We seem to be locked in an ugly cycle over Court nominations. Do you see any way out?

The Supreme Court is still more respected than most other institutions, certainly more than Congress or the presidency. A lot of the hand-wringing over the Court’s legitimacy is a debate among elites. Most Americans don’t think about the Court except when there’s a high-profile decision, and then people’s opinion largely tracks their view of that ruling.

Nomination fights have little to do with structure or process but instead concern product. Every year the Supreme Court rules on half a dozen or so of the most controversial issues facing the country, so the only way to turn down the heat is for the Court itself to devolve power away from Washington and force Congress to legislate rather than punting big issues into the politically unaccountable bureaucracy. Which is to say, there aren’t any easy solutions. It took us decades to get here and it would take decades to unwind.

Interview conducted and condensed by M.F.B.

1 Response

Howard Levine ’53

4 Years AgoBalancing the Court

Is an apolitical Supreme Court impossible to create? I don’t think so. It might be difficult for Congress to agree, but the Court should be apolitical.

An idea has been bothering me for some time, that the Court has been politically motivated for far too long. It is either slanted towards conservatism, or liberalism over the two centuries of its existence, despite the founding fathers’ desire that it be an arbitrator between the congressional majority and the executive branch for much of its existence. Whether the Court is formulated by the Senate, by its power to interview each candidate, the majority of the senators establish the majority of the judges.

It’s time to change that system. How about a Court made up of four Republican selections, and four Democratic selections, with an independent Judge selected by the other eight Judges? It would be obvious that individual would be neither slanted towards either the Republicans or Democrats, and would be the logical choice for being the Chief Justice.

As time changes the direction of the country, fresh thinking is required. To obtain that balance, it would be logical for an age limitation be added to the requirement of selection. With the current longevity, that limitation might now be set at age 80, for a new replacement to be selected. The selection should be made by the representing party’s senators of the judge to be replaced. Thus, depending upon the current thinking of those senators, the choice could be the decision for its selection, without interference by the opposite party.

The question remains, could any Senate accept this seeking of an apolitical Supreme Court? Would it take an amendment of the Constitution to fix the process?

Only a large acceptance by the electorate and a groundswell for reform might make it possible.