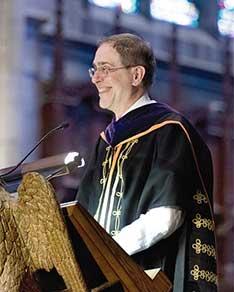

I was delighted that we were once again able to hold Opening Exercises in-person in the Chapel. At the event, I shared with students lessons that I learned from a personal challenge that I have recently confronted. Here is what I told the Class of 2025. — C.L.E.

It is so good to see you. It’s so good to be together. I have missed these moments of collective joy and excitement over the past year.

There is a lot of excitement during orientation. Of course, the college experience is not all, or even mostly, about celebrations or parades. It is first and foremost about learning, growth, and as Jennifer Morton says in her book1, transformation.

I hope you will have many happy experiences along the way, but I know there will also be moments of challenge and difficulty as you travel the path that lies ahead. As you begin that journey today, I would like to share with you a challenge that I have confronted recently, and describe four lessons that I draw from it and that might be relevant to your time at Princeton.

Five years ago, I had a magnetic resonance imaging scan, an MRI for short. The problem that justified the test turned out to be very minor, but the MRI revealed an unrelated issue called an acoustic neuroma.

An acoustic neuroma is a small growth, sort of like the moles that many of us have on our skin. It is, however, in a very tight place, on a nerve deep inside the ear. It is a kind of benign, non-cancerous brain tumor.

When acoustic neuromas grow, they can cause loss of hearing, balance, or the ability to control facial muscles.

I have experienced some hearing loss. I might also have lost a bit of my balance, but I’ve always been a little clumsy, so it’s hard to be certain. I have to be really careful, for example, when I climb the steep, narrow stairs that lead to this lectern.

Fortunately, acoustic neuromas usually grow very slowly, by millimeters per year. Sometimes they stop growing. Those of us who have a small one can wait to see if it grows, or attack it with radiation, or have it surgically removed.

So once or twice a year for the past five years, I have lain inside an MRI tube while the magnets clatter around me, taking pictures of my brain. So far, I have been lucky. My neuroma has not grown.

So why am I telling you this? I said earlier that I draw four lessons from my experience that may be relevant to your own path through Princeton.

The first lesson has to do with how we talk about difficult things. I’ll always be grateful to the doctor who first told me about my neuroma. He said that I needed to come back to the hospital because his colleagues had discovered “a benign growth that had probably been there for a very long time.”

He could also have said, with equal scientific accuracy, that I had a potentially fatal brain tumor. I am really glad he did not say that. The news was hard enough to process even when framed more gently.

The quality of your Princeton education will depend on your willingness and ability to participate in conversations about sensitive and difficult ideas. You might not need to discuss anybody’s lifealtering medical diagnosis, but you will certainly need to talk about profoundly important and emotionally charged topics such as race, sexuality, and justice.

I hope that you will embrace those discussions, both inside the classroom and outside of it. And as you do, I hope you will remember that it matters not only what we say, but how we say it.

We can best learn from one another if we speak to each other openly, respectfully, and compassionately even when we disagree vigorously or when we convey unwelcome ideas. Of course, none of us will get this right all the time. We should hope that others will forgive our mistakes, and we need to be ready to forgive theirs.

The second lesson is about the value of science, institutions, and objectivity. To cope with my acoustic neuroma, I need to believe a lot of amazing things.

I need to believe that noisy magnets can safely take an accurate picture of a growth deep inside my head. I must believe the doctors know without testing it that the tumor is benign, not cancerous, so that we can leave it there. And if it starts to grow, I will need to believe that my doctors can zap it with pinpoint radiation that neutralizes the neuroma without hurting me.

When I lie inside that MRI tube, I think about how lucky I am to live in an age of such scientific miracles. I also consider how fortunate I am to be able to understand a bit of the science and to trust the doctors and institutions who produce it and care for me.

I hope that your Princeton education will increase both your scientific literacy and your capacity to sustain and improve our civic institutions. Those institutions desperately need our attention.

Science, for example, has given us safe and effective vaccines that protect against the COVID-19 virus, but people in this country are dying needlessly because they trust neither the science nor their government. The ability to benefit from scientific understanding and participate in civic institutions is a gift. We should cultivate that gift and share it with others.

The third lesson is about the hidden challenges in our lives. Until I wrote this speech, I had only told ten people about my neuroma.

I kept it secret because I worried about what other people would think if they knew that I had a brain tumor. Perhaps you have had a similar experience, wondering what others might think if they discovered something about you.

Very few people have acoustic neuromas, but everyone has vulnerabilities, pain, and struggles that they conceal from the world. That is true no matter how impressive, authoritative, or composed someone may appear.

When you are dealing with your own challenges — and there will be challenges during your time here! — it can be helpful to remember that you are not alone. Others on this campus have shared similar struggles, and we want to support you.

Conversely, as you interact with people around you — including not only other students but also faculty, staff, and yes, even administrators — I hope you will keep in mind that they may be dealing with troubles that you cannot see or that they are not ready or able to share. That condition is part of what makes us human, and one of many reasons why we need to treat each other humanely.

That brings me to the fourth lesson, which is about humility. I am keenly aware that however much I have accomplished, and however hard I work, I could be laid low by a tiny lesion that I can neither see nor control. Its silent growth could render me unable to stand in front of you or smile as I greet you.

I wish I could tell you that these insights into my own weakness, and the blessings of the good luck and medical miracles I have experienced, have enabled me to savor every moment of life, or to achieve some profound sympathy for everyone I meet.

I am not that good. I still become frustrated, irritated, petty, and depressed, just like everyone else. In reflective moments, though, my diagnosis reminds me that what we do in life, including our ability to reach a special place like this University, depends not only on talent and effort, but also on the care of others and sheer luck. It depends on luck so tenuous that the difference between good and bad may come down to a few unseen millimeters.

I also find myself with new reason to appreciate human resilience and striving. We are all, all of us fragile and flawed, yet we can reach for the stars and do tremendous good. That astonishing combination of weakness and courage is part of what defines the human condition.

We share it. We share it without regard to race, national origin, religion, sexual identity, or political belief. We share it across all the wedges that too often divide us.

The same combination of frailty and aspiration animates the mission of this University. Princeton is a community and an institution where flawed and resilient human beings support one another to learn, grow, cope with our limitations, and pursue the transcendent through scholarship, service, and the arts.

That shared, cooperative quest to achieve our highest aspirations is why we bring you together from around the world to address challenges measured in microns, millimeters, leagues, or light years.

I am happy, indeed I’m downright overjoyed and exhilarated, that you join that quest today. So, to Princeton’s Great Class of 2025, to the Great Class of 2024 that will join us outside for the Pre-rade, and to every undergraduate, graduate student, and staff and faculty member returning to campus this year, I say: Welcome to Princeton!

1. Jennifer Morton, Moving Up Without Losing Your Way: The Ethical Costs of Upward Mobility (Princeton University Press, 2021).