Laura Wooten, a dining hall employee at Butler College, was America’s longest-serving poll worker when she died in 2019 at age 98.

A Black woman born in North Carolina and raised in Princeton, she volunteered at local elections for 79 years, starting in 1939, when the town was still largely segregated, through 2018, when the area’s congressional district reelected its first Black representative, Bonnie Watson Coleman, to a third term.

Lew-Williams, who chairs Princeton’s Committee on Naming, helped to change that this year. The committee recommended naming a campus building in Wooten’s honor, and the trustees approved the selection, changing the name of Marx Hall, which had been up for renaming since 2019, when the University said its donor had been unable to fulfill his pledge.

And so on Oct. 26, in a tent beneath tumbling autumn leaves, about 200 people — including four generations of Wooten’s family, Princeton administrators, Watson Coleman and a dozen local elected officials, and professors from the University Center for Human Values — gathered to dedicate Laura Wooten Hall. Yvonne Hill, one of Wooten’s daughters, said her mom “would be in disbelief that so much ‘fuss’ — one of her favorite words — was being made over what she believed to be her civic duty.

“Some might say she was a shining example of how ordinary people can do extraordinary things and make a difference,” Hill said. “But to us, she was an extraordinary person who did what she believed was ordinary.”

Extraordinary also describes the influx of newly named buildings and spaces around campus in the past five years. Traditional labels such as McCosh and Dickinson halls now neighbor new additions such as Laura Wooten and Morrison halls and Arthur Lewis Auditorium.

While public scrutiny of some of Princeton’s longstanding building names has stirred controversy, the change in the University’s approach to naming has added to the racial, gender, and historic diversity of Princeton. “It was clearly an idea whose time had come [and] probably should have come even sooner,” says Robert Durkee ’69, author of The New Princeton Companion.

Mention the word “naming” at Princeton and likely the first story that comes to mind is one of “renaming.” In June 2020, the Board of Trustees voted to remove Woodrow Wilson 1879’s name from the School of Public and International Affairs and a residential college. It was a decision that President Eisgruber ’83 called “wrenching but right” in a Washington Post op-ed published soon after the announcement, adding that “we cannot disregard or ignore racism when deciding whom we hold up to our students as heroes or role models.”

Examples of Wilson’s racist attitudes — including discouraging Black applicants from applying to the University — had been discussed on campus for decades, but a turning point came in November 2015, when students in the Black Justice League led a sit-in at Nassau Hall, demanding changes to Princeton’s racial climate and calling for the removal of Wilson’s name.

In 2016, an ad hoc committee of 10 University trustees, chaired by Brent Henry ’69, reviewed Wilson’s legacy and recommended keeping his name but providing a clearer view of his “failings and shortcomings.” A mural of Wilson in Wilcox Dining Hall was removed and a towering art installation, Double Sights, designed to be a visual representation of Wilson’s multi-sided legacy, was installed outside Robertson Hall in 2019. The Wilson name remained in place until that trustee vote in 2020.

John Milton Cooper Jr. ’61, a Wilson biographer and professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, freely acknowledges the former president’s “racial sins.” But, like many who objected to the renaming, he was irked by the process, which from the outside did not appear to have the same kind of deliberation seen in 2016. “I think the reexamination of race and Princeton’s role is all to the good and is very much overdue,” Cooper says. “But I don’t think laying it all on Wilson’s shoulders is the right thing.”

Cooper adds that the policy school and college appropriately reflected two of Wilson’s clearest priorities as president of Princeton: preparing students for public service and reorganizing undergraduate campus life around the “quad plan,” a vision that wasn’t implemented in his lifetime but provided a blueprint of sorts for the residential colleges.

To date, Wilson is the only honorific name removed from a University building because of the namesake’s legacy. In 2021, the trustees adopted a set of guidelines for any future renaming that says decisions to rename should be “exceptional.” Proposed changes must be judged on specific criteria, including whether a central part of the namesake’s legacy is “fundamentally at odds with the mission of the University”; whether the namesake was “significantly out of step with the standards” of his or her time; and whether the building or program in question plays “a substantial role in forming community at the University.” (The full guidelines are available online at bit.ly/re-naming.)

But the issue of heroes and role models that Eisgruber raised remains open to scrutiny. Take, for example, three of Princeton’s major Alumni Day awards, named for Wilson, James Madison 1771, and Moses Taylor Pyne 1877. Anthony Romero ’87, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union and the 2020 Wilson Award winner, devoted part of his Alumni Day speech to Wilson’s opposition to civil liberties. The same day, one of the undergraduate Pyne Prize winners, Emma Coley ’20, expressed her reservations about accepting an award named for someone whose fortune was tied to slave labor in the sugar trade. And the 2022 Madison Medal recipient, composer Julia Wolfe *12, noted in her remarks that “Madison spoke eloquently about the evils of slavery, yet he kept slaves and even at his death [in 1836] failed to free them.” She said she’d asked University officials if they would consider renaming the award.

The University has said it will keep Wilson’s name on the Woodrow Wilson Award, in part because it has a legal obligation to do so under the terms of the gift that established it in 1956. University spokesman Michael Hotchkiss declined to say whether Princeton has considered renaming the Madison Medal or the Pyne Prize. “How the University considers questions that may arise related to naming was thoroughly considered by an ad hoc committee whose report outlined five overarching principles about naming, renaming, and changing campus iconography,” he said.

Another famous Princeton name came under fire in 2020, soon after the Wilson renaming at the University. The Princeton Board of Education voted to remove the name of John Witherspoon, an early president of the College of New Jersey and signer of the Declaration of Independence, from its middle school, because of Witherspoon’s history as a slave owner and opponent to abolition. Witherspoon’s name remains on a dormitory at the University, and a bronze statue in his honor stands on a stone pedestal outside East Pyne. In November, after this story went to press, the Committee on Naming announced that it is considering a proposal to remove or replace the statue.

Setting aside the Wilson decision, the University’s approach to honorific naming has typically not been to remove names but to add them. Laura Wooten Hall is one in a series of namings announced in recent years that have recognized diverse individuals. Princeton’s trustees and the Committee on Naming are responsible for these changes, and the process — like the Wilson renaming — can be traced back to the November 2015 Black Justice League sit-in, when students’ demands included changes to campus naming and iconography.

The same trustee committee that reviewed Wilson’s legacy included a two-paragraph section in its report encouraging the administration “to develop a process to solicit ideas from the University community for naming buildings or other spaces not already named for historical figures or donors to recognize individuals who would bring a more diverse presence to the campus.”

Durkee, the University’s vice president and secretary at the time and a member of the first Committee on Naming, says the Wilson legacy review was a catalyst for this new approach to honorific naming, which drew broad support around the University. “There was a lot of interest on the part of students, faculty, and alumni,” he says.

What began as a three-year, ad hoc committee under the umbrella of the Council of the Princeton University Community (CPUC) was renewed for three more years in 2019, and in September 2022, Eisgruber endorsed making it a permanent part of the CPUC. Its status as a standing committee was approved in November.

When the committee formed in 2016, the University had only one building that specifically honored the contributions of a Black person: the Carl A. Fields Center, named for the longtime Princeton administrator and educator who was the first African American dean at an Ivy League institution.

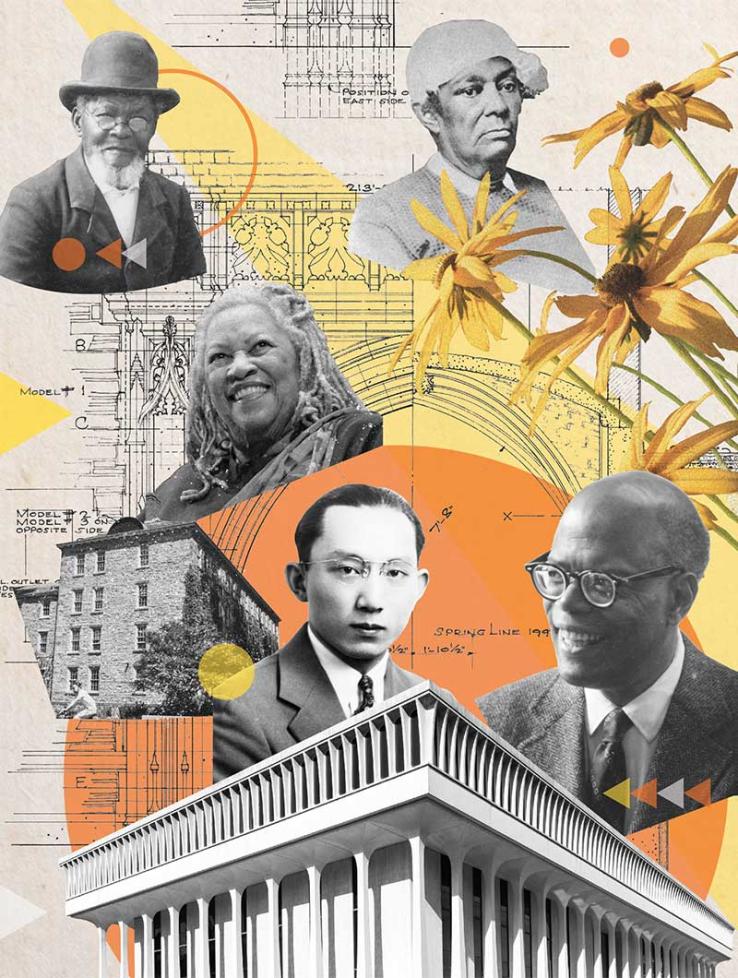

In April 2017, a year after the Wilson legacy report’s release, the naming committee announced its first two selections, honoring a pair of Nobel laureates from the University faculty: West College was renamed Morrison Hall, for creative writing professor and novelist Toni Morrison, and Robertson Hall’s main auditorium was renamed the Arthur Lewis Auditorium, for the late economist who’d served on the faculty for two decades.

History professor Angela Creager, the committee’s inaugural chair, said that Morrison and Lewis added both racial diversity and a diversity of time period to the honorific namings on the central campus, where most named spaces date back a century or longer. They also elevated the presence of faculty. “There aren’t that many spaces on campus that are named after faculty members, so this was a way to really try to get at a core mission of the institution, honoring scholarship and scholarly achievement,” she says.

Names “become part of our vernacular” on a college campus, Creager says. Generations of Princetonians have attended lectures in McCosh 50 or passed under the jutting gargoyles of Dillon Gym. Now, when students visit the dean of the college, they pass a portrait of Morrison inside the building that bears her name. When they listen to a visiting ambassador speak, they sit on the curved tiers of Arthur Lewis Auditorium.

While the first two naming-committee honorees, Morrison and Lewis, represented the modern Princeton, the next year’s choices were drawn from the University’s history and the complicated legacy of slavery. Working with materials from the Princeton and Slavery Project, a multi-year research effort led by history professor Martha A. Sandweiss that included more than 40 undergraduate and graduate students, the committee chose to honor Betsey Stockton, a former slave of College president Ashbel Green who became a celebrated missionary and educator, and James Collins Johnson, who came to Princeton as a fugitive slave and spent 60 years working on campus, first as a janitor and later as a popular vendor of snacks and clothing.

Constance Escher, a local educator and historian who wrote the biography She Calls Herself Betsey Stockton, says that naming a garden next to Firestone Library for Stockton was appropriate because she had “a hunger for learning” and established schools during her travels to Hawaii and back home in Princeton.

For Lolita Buckner Inniss ’83, dean of the University of Colorado Law School and author of The Princeton Fugitive Slave: The Trials of James Collins Johnson, seeing Johnson honored in an archway at East Pyne reflected an “expansion in [Princeton’s] values and a willingness to articulate those changes.”

The latest work of the naming committee addressed another complicated piece of Princeton’s history. In October, the trustees approved plans to honor Kentaro Ikeda ’44, the only Japanese student on campus during World War II. The arch in Lockhart Hall, his undergraduate dorm, will now bear his name.

After the start of the war, the government identified Ikeda as an “alien enemy.” Thanks to a University sponsor, Dean Burnham Dell 1912 *33, he was spared from the internment camps. But as Elyse Graham ’07 wrote in a March 2019 PAW feature, “Ikeda nonetheless found himself in a difficult situation: He was interned on Princeton’s campus, forbidden to move beyond a specified 5-mile radius or to contact his friends and family back home, not allowed to own a camera or shortwave radio, and subject to supervision by a faculty sponsor, with his bank accounts frozen. He spent the war in a gilded cage, wandering the campus but unable to leave it.”

Lew-Williams, who in addition to chairing the naming committee is a historian of race and migration, notes that Ikeda likely was Princeton’s only Japanese student by design: The University refused to participate in a federal program that allowed Japanese American students to leave relocation camps to attend colleges. And Princeton’s anti-Japanese sentiment went beyond the administration (students burned an effigy of General Tojo in front of Nassau Hall when the war ended) and beyond the war years.

“We chose to honor Ikeda in recognition of his endurance when he was confined to campus during World War II,” Lew-Williams says. “We wanted to not only recognize a more diverse group of Princetonians, but also to tell more complex and difficult narratives.”

Honorific names have had a place on campus from the College of New Jersey’s earliest days in Princeton, when the trustees proposed naming its grand new building for an influential patron, Jonathan Belcher, who had helped the College obtain its charter and donated his library to the fledgling institution. Belcher declined, suggesting instead that they name the building in honor of England’s King William III, the Prince of Orange and Nassau — hence, Nassau Hall.

Belcher “was not a person without ego,” says Durkee, who wrote about the naming as part of his work on The New Princeton Companion, published earlier this year. “But he also was a very skillful politician and figured that this young college was going to do a lot better if it’s tied to the British royal family than if it’s got [Belcher’s] name on it.”

The College of New Jersey was distinct among the Colonial colleges in that it was named for its location and not for a founder or benefactor, like William & Mary, Harvard, and Yale. As the campus grew, trustees began to name buildings for their function (Geological Hall, Philosophical Hall) or even more pedestrian qualities like their position on the quad (East College, West College). It wasn’t until 1873 that the College saw its first building named at the request of a donor: Chancellor Green, the new library, which John Cleve Green named for his brother, Henry Woodhull Green 1820, a chancellor in the New Jersey courts.

As the campus expanded, other donor-designated names followed, including Dod Hall (1890), Brown Hall (1892), Alexander Hall (1894), and Blair Hall (1897). In the same period, several buildings were named for past Princeton presidents (Dickinson, Edwards, Witherspoon). Durkee points out that several of Princeton’s greatest benefactors in this period were women, including Susan Dod Brown, Harriett Crocker Alexander, and Margaret Olivia Slocum Sage; each named buildings for male relatives who were alumni or faculty. By the start of the 20th century, nearly every named space on campus honored a white man — not surprising for an all-male institution that was still decades away from conferring its first degree on an African American student. The Isabella McCosh Infirmary was a rare exception.

Among Princeton’s devoted alumni, philanthropy became a source of healthy competition. At his 30th reunion in 1907, Pyne, a trustee and the namesake of the Pyne Prize, rallied classmates to raise enough money to build a new dormitory. “It took the class less than an hour to raise most of the funds,” The New Princeton Companion reports, with more than $77,000 (over $2 million today) pledged by the end of the night. Campbell Hall, named for class president John Campbell, opened two years later.

The days of the one-night fundraising blitz may be gone, but Princeton alumni continue to be generous in supporting the University’s growth. Witness the additions to campus that have opened this fall, each named for an alum or alumni family: In Yeh College, Hariri, Fu, Grousbeck, and Mannion halls; and in New College West, Addy, Aliya Kanji, Kwanza Marion Jones, and Jose Enrique Feliciano halls. In most cases, the University does not release the amount of these naming gifts, but a September 2020 announcement said that Kwanza Jones ’93 and Jose Feliciano ’94, who are married, contributed $20 million, Princeton’s largest gift by Black and Latino donors at the time.

Naming buildings might be seen as an act of vanity or ego, but that view does a disservice to donors, according to Kevin Heaney, the University’s vice president for advancement. “What inspires donors to make gifts of this magnitude is as varied as the donors are,” Heaney says. For some, naming may be a motivator, he says; others are not particularly comfortable putting their name above the doorway but do so out of tradition, loyalty, or “in the hopes of inspiring other people like them to step up and make gifts.” Several recent major gifts to Princeton’s Venture Forward campaign are anonymous for the time being, Heaney says.

The University’s recent push for diversity in honorific naming follows an earlier, more gradual shift in the donor-requested names on campus buildings and programs. Gordon Y.S. Wu ’58’s gift of Wu Hall, which opened in 1983, was a milestone for Asian alumni and international students more generally. It honored his heritage by displaying his name both in English and in Chinese characters.

The ensuing decades have included the opening of the first residential college named for an alumna, Meg Whitman ’77; another college named for Asian American alumnus James Yeh ’87 and his wife Jaimie; and the announcement that Princeton’s eighth residential college will be named for African American trustee Mellody Hobson ’91, who made the lead gift along with the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

When the latter gift was announced in October 2020, Hobson, a first-generation college graduate, said in a University announcement that she hoped her name “will remind future generations of students — especially those who are Black and brown and the ‘firsts’ in their families — that they too belong. Renaming Wilson College is my very personal way of letting them know that our past does not have to be our future.”

Students were a driving force in the calls for Princeton to diversify its honorific naming and iconography, and for Lew-Williams, the naming committee chair, that makes perfect sense.

“They live here,” she says. “This is home. And a lot of things make up that home — the people, and hopefully the academics, and also the portraits and the names. Especially as our student body more accurately reflects the diversity of the nation and the world, it’s important that their home reflects that diversity as well.”

When given opportunities to reshape campus iconography, students have shown an eagerness to embrace the complexity of old and new legacies. In 2018, Butler College students and artist Will Kasso Condry collaborated on a 40-foot-long mural that included images of Toni Morrison and Sonia Sotomayor ’76 emerging between portraits of earlier University icons like James Madison, John Witherspoon, and Woodrow Wilson.

Those senses of complexity and “home” resonate with alumni as well. Inniss was a Romance languages major at Princeton and spent many hours in East Pyne, the department’s home. Now, when she visits that historic building, she can walk through the arch named for James Collins Johnson, whose story she first heard as a freshman, in conversation with an older alumnus who was visiting campus.

Johnson’s life was so compelling that Inniss returned to it decades later, poring through the archives to tell his story in a meticulously researched biography. It wasn’t easy to find written records for a former fugitive slave, but she pieced together a mosaic of stories and recollections, relying on unexpected sources such as student scrapbooks.

Inniss is encouraged to know that Johnson’s name and story will live on — and that Princeton is, in various ways, confronting its legacies of slavery and racism.

“I think it builds a lot of hope that Princeton will continue to reach out and to try to change in ways that help to reshape what has been, sometimes, an incredibly fraught reputation around things like race and gender,” she says. “I’m very hopeful.”

Brett Tomlinson is PAW’s managing editor.

For the Record

This story was updated online to clarify the English royal family’s ties to the House of Orange-Nassau.