When the editor of this magazine asked me to reminisce about being an obituary writer for The New York Times, I was not surprised. He suspected my ruminations as a Princeton alum might captivate readers of the publication’s annual tributes to departed Princetonians. And I had learned from more than a decade on the “dead beat” that people are fascinated by obits to a degree I had not remotely grasped.

After Princeton, I had gone on to cover multifarious things from cowboys and chorus girls to energy policy and jail stabbings for The Wall Street Journal, The Chicago Tribune, and The Times. So when my bosses transferred me to the obits department, it seemed I was being relegated to newspaper Siberia to disappear and quietly expire. I was surprised to find I liked it. A lot. Even though the form demands a ritualized structure, creativity was not just possible but applauded. Obituaries plunged me into compelling topics and controversies, provoking commendation and condemnation from readers who loved or loathed my subjects.

The biggest downside, of course, was not meeting the people I wrote about, and writing about interesting people had been my stock in trade. In my youthful days crafting atmospheric pieces in Texas, I told a friend what a colorful chap I was becoming in the process. “No,” she said with a laugh, “you are not a colorful person. You write about colorful people.”

In the sea of cubicles that is the Times newsroom, the first thing I noticed about the obit area was the décor. A model of a human skeleton hung from a string, a small casket (empty) sat on a counter, and on a wall was the classic New Yorker cartoon of a Times reader saying he first turned to the obit section to find out if he was alive or dead.

I quickly realized that I was surrounded by some of the paper’s best writers, all beguiled by human quirks. And the obit desk, it turned out, had its own peculiar culture. Editors and reporters spoke of prominent people “circling the drain.” One day, Bill McDonald, the top obit editor, asked matter-of-factly, “Who else is hanging by a thread?” Claiborne Ray, his clever No. 2, chirpily replied, “People aren’t dying in the right order, that’s the thing.”

“We need fresh meat,” McDonald, habitually laconic, agreed.

You can well imagine the exhilaration a few days later when Ray announced, “The founder of Kozy Shack rice pudding has died.”

The Times persists in writing full news obits at a time most newspapers have turned to running articles paid for by families of the deceased, many prepared by funeral homes. These can be touching. After a 21-year-old man died in a car crash, an obit in The Mason City Globe Gazette, a paper near my Iowa hometown, said, “Cory liked computers, shooting pool, lifting weights, working out, and bull-riding. His dreams for the future included attending bull-riding school.”

Obituaries can get personal, even for obit pros. For my hometown paper in Iowa, the same one that so grandly told of my great-grandmother’s elevation to heaven, I wrote short tributes to my Mom and brother.

You ached for the kid, but his obit would not have made The Times. And the act of dying has absolutely no place anywhere anymore. The death of my great-grandmother Jacquetta Palmeter in 1930 prompted The Clear Lake (Iowa) Mirror to speak of the instant of her death as “passing over the Great Divide.” The front-page story continued, “It was a fitting instance, that as the sun ceased to shine in the evening the life of this noble woman ceased its work, and she was at rest.”

The Times is more businesslike. It evaluates dead folks on their “consequentiality,” accepting and discarding souls based on how much they changed the world. Using this criterion, I wrote obits of the likes of Geraldine Ferraro and Walter Cronkite. When I said adieu to William F. Buckley, I hailed his “polysyllabic exuberance,” while suggesting some might have deemed him “pleonastic,” meaning the use of more words than necessary. (Yes, I needed a dictionary.)

Sometimes the immensity of events dictates coverage. I reported the death of the last survivor of the Triangle Shirtwaist fire in Manhattan in 1911 in which 146 garment workers died because the owner had locked them in. I told readers about the last two survivors of the burning and sinking of the excursion boat General Slocum that in 1904 killed 1,021 passengers, mainly Sunday school kids from the Lower East Side.

But if a story is a smashingly good story, it demands and earns space in the pages of journalism’s “Gray Lady.” I wrote about Salvatore Altchek, a Brooklyn doctor who made house calls on foot until his late 80s and charged $5 a visit. He sometimes ran into septuagenarians he had brought into the world as babies. He once angered his wife by giving his winter coat to a poverty-stricken patient. Altchek continued working in his office until two months before his death in 2002, and some of his last words were recalling that he owed a patient a medical report.

In 2001, I wrote about Gino Circiello, who created a magical restaurant on the Upper East Side, named it after himself, and pasted wallpaper featuring zebras leaping against a fire-engine-red background on all the walls. Ed Sullivan was a lunch regular, and Frank Sinatra always took the big table in back. “Mr. Circiello, with his hair slicked back like George Raft’s, and an elegant suit draped over his slender frame, stood at the front, using his rasping voice to greet everyone like a treasured relative,” I wrote. His wife, NiNi, said he belonged to “a world that doesn’t exist anymore,” and Gay Talese, a devoted regular, said he was a human time capsule.

I chronicled the life and times of Sam Lewis, head of the World Armadillo Breeding and Racing Association; Steam Train Maury, who was elected King of the Hoboes five times; and Ed Peterson, who spent most of his 100 years collecting wildflower seeds, naming many species. For the last five years, he was legally blind and relied on companions’ descriptions to claim new discoveries.

Megan Boyd tied enchantingly exquisite fishing flies that were prized by piscatory types and earned her the British Empire Medal. She did not collect the award from the queen because she had to take care of her dog that day. When Prince Charles, a big fan, asked her to whip up a masterpiece or two for his tackle box, Boyd declined because she had made plans to attend a Scottish dance in her village. Her house had no electricity or running water and she cut her own hair. Boyd never charged more than a dollar or so for a fly that others sold for $1,000. In her whole life, she never went fishing.

Unless there are special reasons, the obit form mandates strict conventions. You must give the age of the deceased, almost always in a second short sentence at the end of the first paragraph. In the first sentence of my obit of Selma Koch, owner of the Town Shop, a popular lingerie store on Broadway at 82nd Street, I lauded her global reputation for helping women find the right bra size, “mostly through a discerning glance and never with a tape measure.” It was my ensuing words that dazzled, absolutely dazzled the cosmos. Here they are: “She was 95 and a 34B.” No one has ever received more comment for six words that aren’t in the Bible. Her son loved it.

Obit reporters’ time was divided between long projects on important people still alive and people we had just learned had died. I mainly did daily pieces, slaving under the iron law of journalism: News is what you know at the time. But I did interview Nicholas Katzenbach ’43, a former attorney general. He was in a POW camp in Germany after his bomber had been shot down during World War II. So was my Dad, a glider pilot. Katzenbach’s memories were gripping to me.

Obit. Life on Deadline

Watch the 2016 documentary about obituary writers at The New York Times, available on various streaming platforms.

I never made the biggest mistake possible on the obit desk — printing a farewell to someone who hadn’t died. (The paper has done it a couple times.) Once, though, I called up the family of a man who was reported to have died, and the guy who answered was him. Other times I antagonized readers by emphasizing what made an individual famous: One of Nixon’s Watergate bagmen grabbed our attention because of that nefarious exploit. His family was furious that I didn’t emphasize his later civic and charitable contributions.

And you can never know how time will change what you write in an obit. Often called the first draft of history, they might turn out to be exactly the opposite. In its 1924 tribute to former Princeton president Woodrow Wilson 1879, The Times hailed his battles against the “aristocracy” of the college’s eating clubs, calling this “a dramatization of the struggle against ‘special privilege’ which was then agitating the country.” Now, Wilson’s name has been summarily removed from the graduate school I attended because of his undeniable racism.

But obits are not a literary straitjacket. Occasionally, you could soar beyond the confines of the standard obit. I am very proud of beginning an obituary with a joke. Coot Matthews was the trusted partner of Red Adair, the vaunted battler of oilfield fires. (You cannot be more “vaunted” than to have John Wayne play you in a movie, in this case, Hellfighters.) Adair and Matthews, he-men to the core, insisted on the word “kill” rather than “extinguish” as the proper term for battling infernos.

The joke has St. Peter showing a Texan around heaven, with the Texan claiming that everything he saw was better in Texas. St. Peter tired of the schtick and pointed to the fire of hell. “Do you have anything like that in Texas?” he asked. The Texan said no, then added, “But there are a couple of good ol’ boys in Houston who can put it out for you.”

My favorite quote, maybe from any story I’ve ever written — obit or otherwise — concerned the passing of Melvin Burkhart, a sideshow performer who wrestled snakes and regularly survived an electric chair but was best known for hammering nails and spikes up his nose in front of millions of Americans in thousands of places. “The Human Blockhead,” he billed himself. The following quote came from Todd Robbins, a magician and author who sometimes performed his own blockhead act. “Anyone who has ever hammered a nail into his nose owed a large debt to Melvin Burkhart,” Robbins pronounced.

Obituaries can get personal, even for obit pros. For my hometown paper in Iowa, the same one that so grandly told of my great-grandmother’s elevation to heaven, I wrote short tributes to my Mom and brother. For Eileen, I remembered the story of having little tea parties on a stump in the grove on her family farm. I told of my younger brother, Steve, teaching himself to read when he was 3 by watching quiz shows on TV and devouring almost the entire World Book Encylopedia by the time he started school.

And then there was Danny Perasa. He worked in The Times’ communications department handling correspondents’ communications from around the world and later for Off Track Betting. He was a real-life Brooklyn leprechaun who dyed his beard green on St. Patrick’s Day and wore a diaper and sash to greet the New Year. To cope with diabetes, Danny walked long distances all over New York City. I began to accompany him and over the years we trod the circumferences of Manhattan and Staten Island and much, much more. I wrote stories about our treks, all of which were essentially streams of Danny wisdom.

“Maybe I’ve still got the instincts and intellect of a 6-year-old,” Danny said as we giggled at the giraffes in the Bronx Zoo. “And maybe I’m better off for it.”

Danny achieved national fame by periodically spinning tales for StoryCorps, NPR’s wonderful oral history project. The most touching tales involved his wife, Annie, a nurse whom he asked to marry on their first date. He left a love letter to her on the kitchen table each morning. As Danny approached certain death at the age of 67 — and I fell into a routine of stopping by his apartment to chew pastrami sandwiches and wisdom — he limped to the StoryCorps booth in Grand Central Terminal and talked. And talked. Many thousands listened across America. They surely wept when he told how Annie would ask him each night if he would like a little ice cream. “Those aren’t very dramatic things to say,” Danny said in his old-time New York accent, “but they stir my heart.”

My boss let me write Danny’s obituary largely because he had appeared in Times stories I had written over the years. His death prompted an avalanche of emails to NPR. A man said the last story Danny told on the radio had persuaded him not to separate from his wife as he had planned. A woman mentioned that her sudden tears dissolved mascara she had just applied.

And, yes, it is possible that I may have shed a tear myself.

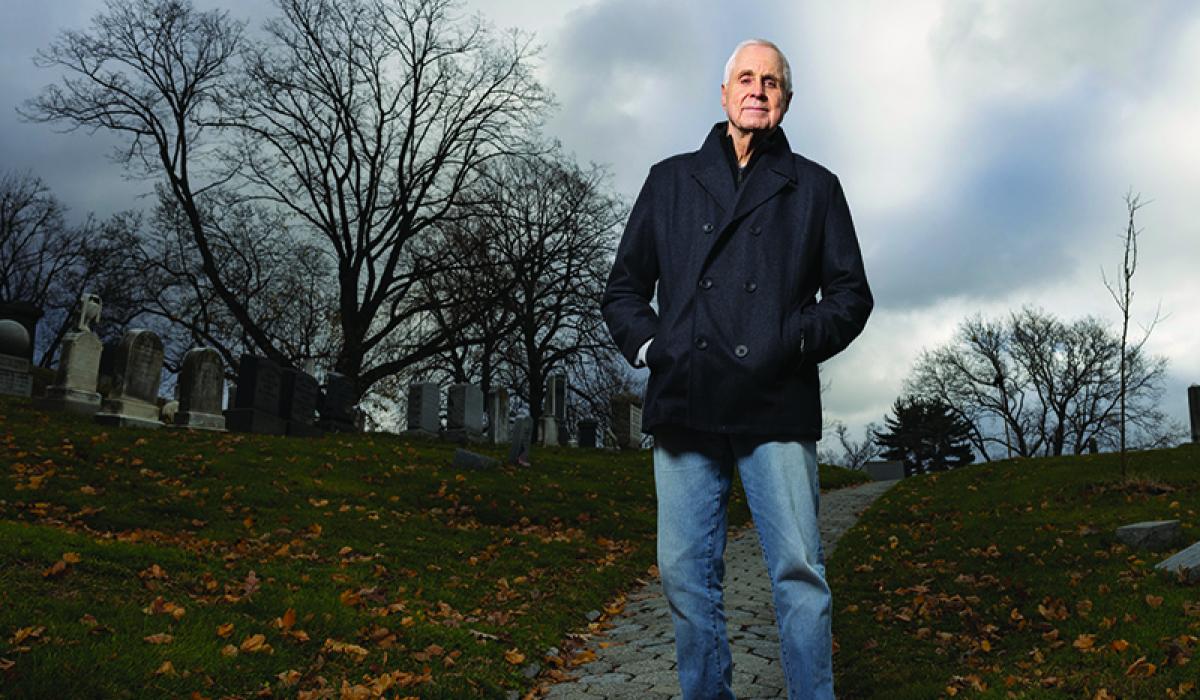

Douglas Martin *74 earned degrees from Dartmouth and the London School of Economics and Political Science before attending Princeton’s public affairs school in 1973-74. He took a buyout from The Times in December 2014. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife, Suzanne O’Keefe, with whom he has two sons, Roy and Guy.