The lawmakers who enact the federal budget work in marbled splendor on Capitol Hill. But just a few blocks away the Congressional Budget Office, which analyzes those budget figures and ensures their integrity, is tucked away on a middle floor of the utterly nondescript Ford House Office Building.

There, where D Street leads into the on-ramp for I-395, the décor is fluorescent lighting, dropped ceilings, and linoleum tile, which is a bit underwhelming considering that the CBO is one of the most useful arms of the legislative branch. On a chilly Wednesday in early January, just a few hours after the 112th Congress took office, CBO director Doug Elmendorf ’83 issues an analysis of the country’s fiscal future that is as spartan as the government-issued table he sits behind. A tall, lean man with glasses and a closely trimmed beard, Elmendorf looks very much like the policy wonk he is. His job is to be analytical and nonpartisan, so he chooses his words carefully.

“Predicting the deficit is very difficult, because you are trying to predict the difference between two very large numbers,” he says, referring to government revenues and outlays. “But I think there is no doubt that the underlying structural factors affecting the budget deficit are adverse under current policy.”

Translation: We are deep in red ink and getting deeper.

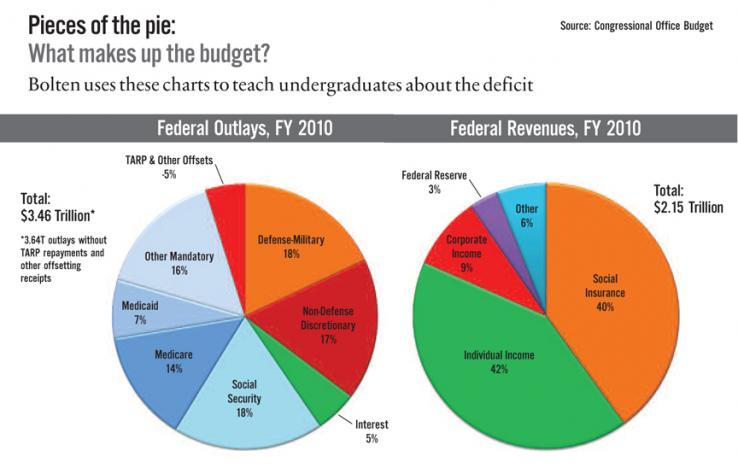

Several weeks later, another Princetonian, Joshua Bolten ’76, gave much the same assessment — this time, in an underground classroom in Robertson Hall. Bolten, who served as director of the Office of Management and Budget (the budgetary arm of the executive branch) from 2003 to 2006 and as White House chief of staff during the last three years of the Bush administration, taught a six-week graduate course, “Averting the U.S. Fiscal Crisis,” this semester in the Woodrow Wilson School. (Bolten taught a companion course for undergraduates last fall.) Fifteen students studied the budget — how it is developed, what goes into it, and how the gaping fiscal imbalance might be fixed. At the second class meeting, Bolten laid out the bad news in a series of PowerPoint slides.

According to the CBO, he showed, the federal government last year took in $2.15 trillion but spent $3.46 trillion, leaving a deficit of $1.31 trillion. In the current fiscal year, the deficit is expected to go even higher, to about $1.5 trillion, and under the Obama administration’s proposed budget for the 2012 fiscal year, which Congress already has begun debating, the deficit would be $1.65 trillion.

Numbers that large are difficult to imagine, but a trillion one-dollar bills stacked on top of each other would reach more than a quarter of the way to the moon. A more informative way to look at the deficit, though, is as a percentage of the country’s gross domestic product. Bolten’s slides show that over the last half-century, the annual deficit has averaged about 2.5 percent of GDP. Even during the 1980s and early 1990s, when many were calling for a constitutional amendment to eliminate Reagan-era deficits, it never got above 6 percent.

But last year’s deficit was 8.9 percent of GDP, down slightly from 2009’s 10 percent, which was the highest it’s been since the Cold War. Under the CBO’s worst-case scenario it could rise to more than 32 percent by 2035. The national debt — the cumulative total of all the deficits we have run over the years, offset by any surpluses — jumped from 36 percent of GDP as recently as 2007 to 62 percent last year and could, the CBO projects, go as high as 185 percent by 2035. Even if it remains in its current range, most analysts agree that such a level of debt is not sustainable.

Some economists dismiss the notion that the deficit requires massive budget-cutting immediately and at any cost. Princeton professor Paul Krugman, winner of the Nobel Prize in economics, wrote in The New York Times on March 10: “The nation is not, in fact, ‘broke.’ The federal government is having no trouble raising money ... So there’s no need to scramble to slash spending now now now; we can and should be willing to spend now if it will produce savings in the long run.” Krugman argues that the nation’s long-term deficit problem is driven mainly by health-care costs, so policymakers “should be looking for ways to rein in health spending over the long term” — by spending on things like prevention and research.

“The deficit we have right now is not a massive national threat, but the deficit that is projected for the future is a massive national threat if we don’t deal with it,” says Peter Orszag ’91, who served as CBO director from 2007 to 2008 and as OMB director in 2009 and 2010. “The challenge that we have is that we don’t tend to deal very well with problems before they become crises. We are on an unsustainable path, and it’s not clear how we get off of it without suffering severe injury.”

What might that “severe injury” be? The CBO helpfully laid out such a doomsday scenario last summer in a policy paper, “Federal Debt and the Risk of a Fiscal Crisis” (available online at www.cbo.gov). Currently, when the country runs out of money, it simply borrows more by selling government debt (Treasury bills) to private and institutional investors. Much of it is bought by foreign governments, especially China, which is now the largest single foreign holder of U.S. government debt.

If the financial markets concluded that our debt had grown beyond our ability to repay it, investors might stop buying it. The government would have no choice but to raise interest rates to whatever level was needed to lure those investors back. If interest rates on Treasury bills were to rise by even 4 percentage points, the CBO estimates, federal interest payments would increase by 40 percent — which would only make the deficit even bigger and accelerate what Orszag calls a “vicious feedback loop.” An increase in interest rates also would reduce the value of government bonds that already have been sold, which might force some of the mutual funds, pension funds, banks, and insurance companies that hold them into bankruptcy.

Alternatives would be, as the CBO puts it, “limited and unattractive.” They include rampant inflation, if the country chose to print still more money; large, overnight tax hikes, which could shove the economy into another deep recession; or deep and immediate cuts — perhaps 25 percent or more — in Social Security and Medicare. With the government’s credit cards maxed out, so to speak, there also would be no way to spend additional money in response to an unexpected national emergency.

At what point would things collapse, and how much time do we have? “That,” Bolten jokes in an interview, “may be the $64 trillion question.”

“A lot of it is a function of market psychology,” says Gregory Mankiw ’80, a Harvard economist who chaired the Council of Economic Advisers from 2003 to 2005. “In general, the bond market has tended to give the U.S. the benefit of the doubt.” That is to say, investors keep buying our debt because we have the biggest economy, the dollar remains the world’s reserve currency, and we are perceived as a safe, politically stable place for their money.

Panics, however, tend to happen during economic downturns, and when they happen, they often arrive suddenly but with sickening speed. The CBO suggests that the United States is not facing a Greek-style collapse — yet. But the longer we wait to address the deficit, the greater the risk — and the less room for maneuvering if a crisis comes.

Orszag agrees that it would be a grave mistake to cross our fingers and hope for the best. “People assume that we’re the United States, it can never happen to us,” he says of a fiscal collapse, “but we have never on a sustained basis run excessive budget deficits over an extended period of time, outside of a war.”

One crucial decision would have to be made this spring. Federal law limits how much the government can borrow, and we were expected to reach that “debt ceiling” as early as March 31. But there have been rumblings — particularly within the Tea Party — about not doing that this time. Economists feared that a refusal to raise the ceiling, or even a credible threat to do so, could be the event that saps lenders’ confidence that they eventually will get their money back.

“We don’t have any recent experience in this country at defaulting on the federal debt,” Elmendorf says. “And I don’t know any analysts who think we should experiment and see what happens.”

There are, economists explain, two parts of the deficit problem. Much of our current deficit is attributable to the 2008–09 financial meltdown (the 2007 deficit was just $161 billion, a little more than a tenth of what it is now). Tax revenues fell, automatic stabilizers such as unemployment insurance kicked in, and the government administered a strong dose of Keynesian stimulus to jolt the economy out of recession. As the economy improves and tax revenues pick up again over the next few years, the deficit is expected to shrink, although the budget would be nowhere near balanced. But over the next 20 years or so, the deficit will begin rising again — and this will be a much harder problem to address, because it is structural. Most of that gap will be caused by rapidly rising expenditures on health care, particularly Social Security and Medicare, as the baby boomers grow old.

Last December, the Obama administration reached a deal with congressional Republicans to extend the Bush tax cuts for two years in exchange for measures designed to stimulate the economy and create jobs. In the short term, that added almost another trillion dollars to the deficit. That might seem to be exactly the wrong move, but Elmendorf is among the economists who say a short-term stimulus when the economy remains weak is not inconsistent with long-term fiscal restraint, even if it is paid for with more borrowed money. The problem is that the borrowing occurs now, and the belt-tightening is put off again for another day.

There are two main ways to reduce any deficit: Cut spending or raise revenues. Conservatives tend to favor the former; liberals, the latter. Any solution almost certainly will have to include both. Simply allowing the Bush tax cuts to expire in 2012 would cut the projected deficit by $600 billion. But doing so now could stall the economic recovery and would face strong Republican opposition. Although many have focused on cutting discretionary spending — that part of the budget that funds everything except defense, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, interest on the debt, and other mandatory payments — such spending accounts for only about 17 percent of the budget. Another suggestion, eliminating congressional earmarks, accounts for less than 2 percent of federal expenditures. Both Congress and the administration are learning just how hard the choices really are.

Orszag says that the health-care reform legislation enacted last year will curb the growth in health-care expenditures and reduce the long-term deficit — assuming it is funded and implemented. There also have been at least a dozen serious proposals to reduce the deficit going forward, and Bolten’s class was to examine each of them and assess their strengths and shortcomings. Bolten admits to being partial to a plan by Wisconsin Rep. Paul Ryan, the new chairman of the House Budget Committee, whom Mankiw, another fan, praises as “the most serious person on the Republican side.” Ryan would make vast changes in the way government operates, privatizing part of Social Security and Medicare; providing a refundable tax credit to pay for health insurance; eliminating the estate, corporate income, and alternative minimum taxes; and placing a binding ceiling on total government spending.

Last December, the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, chaired by former Republican Sen. Alan Simpson and former White House Chief of Staff Erskine Bowles, a Democrat, issued a long draft report that advocated, among other things, cutting defense spending, increasing the gasoline tax, raising the retirement age for Social Security, and limiting Social Security and Medicare benefits for the wealthy. Mankiw has written favorably about some proposals to raise revenue by broadening the tax base, eliminating such sacred cows as the deductions for mortgage interest and state and local tax payments, and taxing employer-provided health-care benefits. (Though it drew some bipartisan praise, the commission’s draft report drew criticism and could not command enough support from its own members to be issued officially.)

Around the same time the Simpson-Bowles draft came out, the CBO issued another paper, “The Economic Impacts of Waiting to Address the Budget Imbalance,” in which it pointed out that straightening our fiscal house in 2015 would require tax hikes or revenue cuts equal to about 2 to 2.5 percent of GDP. Wait another 10 years until 2025, though, and we will have to raise or cut about 8 to 9 percent of GDP. “Ultimately the fiscal imbalance will have to be addressed,” the report concludes, “whether quickly or gradually, and the longer the necessary adjustments are delayed, the more drastic they will need to be.”

“Our political system has never dealt well with gradual long-term problems,” Orszag observes. “It deals with crises. You can’t credibly go to a member of Congress today and say, ‘If you don’t fix this problem now, the bond market’s going to collapse tomorrow.’ You can continue to [use that rationale] tomorrow, and the day after that, and the day after that, and the day after that.” Until the day finally arrives when it does collapse.

Mankiw, for his part, cites with hope Winston Churchill’s observation that Americans will always do the right thing — after they have exhausted all the alternatives.

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.