Like many other American boys who grew up watching World War II movies in the 1940s, my old roommate Peter Clapper ’49 came of age wanting nothing so much as to get into the fight.

“I wanted in,” he wrote later. “I wanted action.” But he was just a few months too young.

Eventually, in the Korean War of the early 1950s, he got his chance and, by all accounts, he was a superb and courageous leader.

But the years since Korea brought many disappointments, not so much confirming the old adage about being careful what you wish for as supporting its corollary: Getting what you want most can come at a high and lasting price.

Recently, I spent a couple of days in Denver, visiting Pete and trading old stories. It did not take long to realize that the story that really needed to be told was Pete’s own, beginning two days before Christmas in 1951.

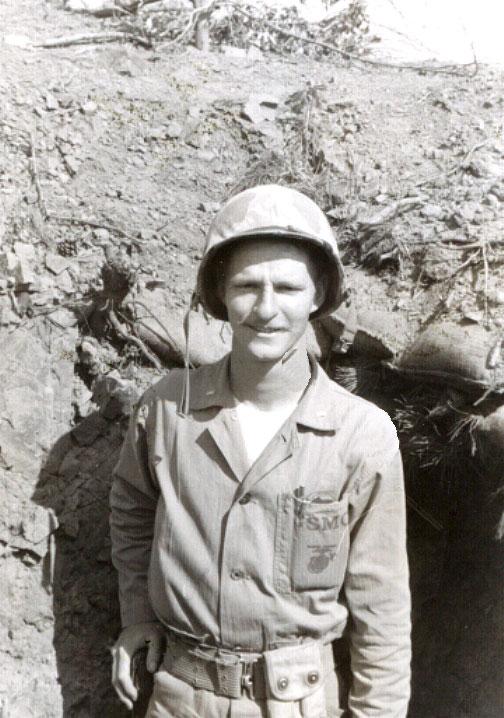

That cold winter Pete was a 24-year-old Marine infantry platoon leader on the Main Line of Resistance dividing U.S. and South Korean troops from the North Koreans. Each side was dug into the frozen ground of the mountains rising on either side of the So Yang Gang River, near the Sea of Japan. Each side sent out patrols to try to surprise and kill the other.

Pete was ordered to take a squad down his side of a mountain called “Hill 854,” looking for any sign of the enemy. He wrote later, “I dropped down a few feet to the left of the trail and became entangled in some rusty barbed wire there at exactly the moment that the enemy opened up on the trail from down in front of us.”

“As the first shots rang out,” Pete continued, “something amazing happened to me. I got out of the wire, onto the trail, and gave a huge enraged shout which echoed down the canyons. I charged straight down the trail toward the enemy.”

Pete was bleeding from his face and hand, but he kept on firing his M1.

“Suddenly it was as quiet as could be,” Pete remembered. The North Koreans had withdrawn.

Two of Pete’s men also had been wounded, but everyone in the squad made it back. “I like to think that my blood-curdling yell scared the North Koreans away,” Pete said. “I know for a fact that it scared my men. They told me so.”

Much later, looking back, Pete reflected, “It is given to few men to successfully charge the fire of his country’s enemy. I was granted that privilege. I still can’t figure out why.”

Pete went on to command a tank company with its ear-splitting guns, and then he came home. He brought with him a thin white scar across his forehead where a bullet had grazed him, frost-bitten feet, and a constant ringing in his ears.

He wrote later, “Sometimes it’s like a railroad whistle. Sometimes it’s like a police siren or bells. Sometimes it’s all of the above, but it’s always there when I’m awake. … These silent sounds inside my head are the echoes of the great 90mm tank guns of which I was so proud and with which we did so much damage.”

It would be many years before the effects of Pete’s combat experiences were diagnosed as post-traumatic stress disorder.

Pete had always lived with a sometimes-fierce intensity. He had a great capacity for hard work and self-discipline, and, like many relatively short men, he stood erect and walked fast. He also had a hair-trigger temper, which seemed to go with his thick red hair.

One day, in a 150-pound football game, an opposing player did something Pete did not like so he punched him, full strength, in the face. Ever after, his teammates fondly called him “Slugger.”

Happily, along with the ferocity, Pete had and still has a winning capacity to laugh, especially at himself. When he made some gaffe or said something ridiculous, he would shake his head and say, “I kill me.”

He also had a talent for drawing, especially cartoons, and when I visited him I was reminded of his knack for one-liners. I had recalled some adventure we had had and he said, “Don’t make me laugh, I’ll cry.”

Later, he noted, “If you live long enough, you’ll never die.”

Pete’s father, Raymond Clapper, a famous newspaper columnist, had been killed in 1944 covering World War II. His mother was a charming, elegant woman who became the head of CARE.

Pete enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1944, during his last year at The Hill School, where I first knew him, and as soon as he graduated he was ordered to Parris Island, S.C., for boot camp.

In the early summer of 1945, “P.I.” was known not only for its domineering drill instructors but for the fateful message being instilled in all new Marines – that they almost certainly would die within just a few months in the looming invasion of Japan.

And then, suddenly, with Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the war ended. Pete was discharged, and he entered Princeton. I do not remember him ever expressing amazement at his abrupt transition from a Marine barracks to Cuyler Hall and a senior thesis comparing Hawthorne and Dreiser. But I do remember him saying that the atomic bomb probably saved his life.

After graduation, Pete became a police reporter for The Washington Post, joined the Marine Corps Reserve, and promptly was called to active duty. He went through Officer Candidate School, was commissioned a second lieutenant, and quickly was flown to Korea and, at last, “his” war.

Pete was almost killed, many times. He wrote later that, over and over, he felt he survived because of “fantastic luck.” But eventually, he remembered, he began to feel “vulnerable.” When his tour was up, he gratefully came home.

Returning to the United States, however, brought Pete a lot of disappointment. He recalls that no one seemed to care where he had been or what he had done, and no one thanked him for his service.

He got a job as a writer for CBS News in New York, but it did not last. He moved to Denver, and ran a copying store for a while. He was married and divorced twice. His mother, in Washington, had to be hospitalized with Alzheimer’s, and she died. His sister also passed away. Pete kept up with his daughter from his first marriage, but they see each other now only occasionally.

He did become a commercially licensed pilot, and worked briefly at the Federal Aviation Administration. He also got a master’s degree in environmental management from the University of Southern California.

When Pete was a senior at Princeton, his G.I. Bill eligibility ran out and he needed financial aid. The University helped, and he since has returned the favor. He had inherited some stock in Procter and Gamble, where his paternal grandfather had worked as a janitor, and he gave it to Princeton to manage, for income for himself until he dies and then, every year, for a needy senior – The Pete Clapper ’49 Scholarship.

Twenty-five years after the Korean War, and shortly after Vietnam, researchers finally named and publicized post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Pete discovered a book about it and wrote the author, Patience Mason, to thank her for getting right what he called “many of my own long-term reactions to wartime experiences.”

“I thanked her for the book,” Pete said, “and she thanked me for my service.” Indeed, it was Patience Mason, a stranger, who was the first person to do that.

Another kind of thanks came from Pete’s former sergeant, William Bussey, who now is retired in Arizona. Bussey wrote a poem about Pete that said, in part,

“He didn’t know fear, or so it appeared to the troops.

“He got shot in the face, not bad, just made him mad.

“He stood there screaming and firing all he had.

“Damn he was good. He did things no one ever figured he would or could.

“But he brought us back …. He was wild, crazy and tough as a boot, with a mind very keen. And after fifty-some years he’s still the best Marine I’ve ever seen.”

Pete always has been known for his straight talk, not least to authorities. Once he was being fitted for hearing aids at Denver’s V.A. hospital, and he was asked to take a test. One of the questions was, “Have you ever considered suicide?”

“Sure,” Pete responded. “Hasn’t everyone?”

When he was diagnosed with PTSD, his reaction was one of unqualified delight.

“Now when I do something strange,” he said, “I can blame it on PTSD.”

But PTSD is by no means of merely casual interest. Pete still hears the “echoes” of those 90mm guns, echoes that recently changed, he said, from their earlier sirens and bells to what Pete called a “lousy men’s chorus.” The sounds in his head have never stopped, and when he commented on a draft of this article he wrote, “The PTSD stuff is real important, and people need to know about it. We keep creating more and more of it, and it does not go away.”

And then he added, “It isn’t contagious, though.”

In his mid-80s now, Pete lives by himself, frugally, in an apartment just south of Denver. He still skis and still plays tennis, and his second ex-wife, who lives just five miles away, looks in on him. They are best friends, and go to the movies together and out to dinner.

Pete told me, “I’m happier than I have ever been.”

Bob Abernethy ’49 *52 is the host and executive editor of the public-television program Religion & Ethics Newsweekly. He was a correspondent for NBC News, and served in the 1970s on the University’s Board of Trustees.