If only for a short time, there was some happiness in Patrick Anderson ’75’s childhood: swimming in a slough off Alaska’s Prince William Sound, eating fresh herring eggs, and picking berries for his large extended family and placing them into empty 3-quart cans. It was a traditional life of Tlingit and Aleut peoples in Cordova, Alaska, in the early 1960s. But when Anderson was 8, his family moved to Seattle, where his stepfather expected to find work. When that didn’t happen, the couple split, leaving Anderson’s mother destitute.

She picked strawberries and vegetables and gathered ferns for a florist, but couldn’t balance the work and child care, and Patrick and his four sisters were removed by authorities. Without a foster-care placement available, Anderson was held at a youth-detention center over a winter at age 10, where he slept on a cot in a huge room and was marched to meals.

“I cried for the first week that I was there. I didn’t want to eat or talk to the social worker,” Anderson says. “You’ve got to survive. You were surrounded by kids who were there for a reason, and you were just there because you didn’t have a home.”

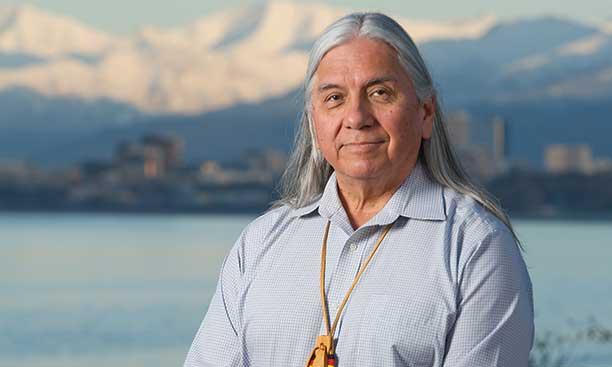

In a sparse office in Anchorage, Anderson tells his story slowly and precisely in a deep voice. The issue of childhood trauma has become a driving force in his life’s work.

His family eventually was reunited, living in extreme poverty, a lifestyle that was punctuated by overcrowding, frequent moves, and his mother’s abusive boyfriend.

“I didn’t like home,” Anderson says. “I would escape by going to the library and reading books.” He also joined school sports teams, a choral group, and band to get out of the apartment early and return late. A high school counselor who previously had placed an athlete at Princeton noticed him and told him she thought he could get in if he applied.

“I said, ‘That’s nice. ... What’s Princeton?’” Anderson recalls.

At the time, Princeton was admitting a growing number of indigenous students, and Anderson enrolled. His memories of freshman year begin with his delight at eating regularly and sleeping in a safe, comfortable room. Anderson lists more than a dozen Native Americans who started at Princeton around the same time he did, but many quickly dropped out, and several of those who made it through had come from elite prep schools. Anderson, in comparison, had never written a research paper.

Fear of failure — and of poverty — got Anderson through, along with help from dorm friends. He paid for college with scholarships and work. The Bureau of Indian Affairs covered half his tuition. He got into an eating club, but couldn’t afford the fees.

After graduating as a Woodrow Wilson School concentrator, Anderson went to law school at the University of Michigan. Native-owned corporations had received a settlement of 44 million acres of land from the federal government not long before he began practicing law, and he was in high demand.

But Anderson says he struggled to find a happy balance in his life. He reached a turning point after a sister died in 2000. She had struggled with drugs and an unhealthy lifestyle, problems endemic to Native communities, which reminded him of his own problems with obesity and failed relationships.

“I re-evaluated, do I really want to practice law? Why did this happen?” he says. “In 2003, I decided I would leave the practice of law and see if I could help remediate what I saw as a problem.”

Anderson has worked in Native nonprofit and health organizations since then. In July 2018, he was appointed CEO of the federally sponsored Rural Alaska Community Action Program, which provides housing, health, and early-childhood services. In Alaska, rural means really rural, as the organization’s clients often come from roadless villages and survive partly by hunting and gathering.

Ten years ago, he read a Centers for Disease Control report on the theory of adverse childhood experiences, the idea that traumatic life events during formative years can predict difficulties later in life. “My world changed very quickly” after reading the report, he says. Anderson had worked with tribal grants on suicide prevention, but now realized more attention was needed on the root cause: childhood trauma.

Anderson says Alaska Natives have double the number of adverse childhood experiences as the rest of the U.S. population. The CDC study shows that the likelihood of adverse consequences later in life — such as smoking, IV drug use, obesity, and suicide — rise proportionally to the number of traumatic events in one’s childhood.Anderson sees his own hardships reflected in the research. He has been addicted to sweets, has had problems with anger, and, after three divorces, has felt crippled in his relationships.

Addressing childhood trauma, he says, is bigger than any one organization. As tribal health director of the Sophie Trettevick Indian Health Center in Neah Bay, Wash., he started a program to address trauma, using the CDC’s rubric to measure adverse experiences to predict patients’ needs. In Alaska, he has given speeches, successfully supported legislation, and worked with tribal groups to increase awareness of the malicious cycle of childhood trauma within the entire Alaska Native community.

Anderson believes that cycle originated with racism and cultural destruction experienced by earlier generations. Anderson’s own mother was taken as a young girl from her home to a government boarding school, part of forced separations during the mid-20th century that emptied Alaskan villages of children.

“The historical traumas have led into an intergenerational transfer of traumas,” he says. “It’s not unusual [for Native Alaskans] to have an alcoholic parent or to have a parent who has been in prison.”

Anderson credits the ways in which Princeton has shaped him, even though in Alaska’s egalitarian society, especially the Native world, his Princeton connection often felt more like a barrier than a boost.

“One thing that really made a difference is I met people who really knew how to think and reason,” he says. And the diploma meant something, too. “It showed I could take on a major challenge in my life and succeed at it.”

Charles Wohlforth ’86 is a writer based in Anchorage, Alaska.