As the world commemorates the 75th anniversary of the Allied invasion of Normandy, we looked back in the PAW archives to see how alumni described D-Day — the anticipation of the operation, the day of the landing, and the months of fighting that followed.

The first mention of D-Day was published in the Class of 1943 notes column June 2, 1944: “Johnny Newbold [’43] is in England with the amphibious forces waiting for D-Day to come along. He says he has been looking for any of the class for three months now, in vain.” Newbold, a Navy lieutenant, returned to civilian life after the war and worked in investment banking until his death in 1968.

In July 1944, PAW shared the story of Lt. George McNeill ’41, a Silver Star and Purple Heart recipient who would come home to New Jersey after the war. McNeill landed with the early waves in the Normandy invasion and was sitting down to eat his K ration on D-Day-plus-3 when he noticed a familiar label on the sugar packets: Princeton Campus Club. “Presuming on neighborliness (he is a member of Tower Club), Lt. McNeill ate the sugar — and subsequently mailed one of the wrappers home,” PAW reported.

The Aug. 11, 1944, issue carried news of a casualty in the Normandy invasion: “On D-Day, June 6, 1st Lt. Jerry Schaefer [’40] was killed in action in France. Jerry was a member of an airborne artillery outfit and had previously seen action in Sicily and in the Allied landings in Italy. To his parents and to his widow, Mrs. Margaret Schaefer, we extend our sincere sympathy.” Schaefer is one of 355 alumni who died in the war. His place of death is listed as Sainte-Mère-Église, France, which is now home to the Airborne Museum, dedicated to the memory the U.S. Army’s 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions.

The Oct. 6, 1944, class notes for 1939 mentioned that classmates Dana Burke ’39, Fred Fox ’39, and Chuck Backus ’39 “were in the same attacking force when they landed in Normandy.” PAW readers would later learn that Fox was part of the Ghost Army unit, which used inflatable tanks, sound-effect records, and phony radio chatter to give the German army false information about where the Allied troops were located. (See story in the March 21, 2012, issue.)

The general tone of alumni dispatches during the war was one of calm reassurance. Descriptions of the fighting were rare. The father of Navy Lt. Jack Daniel ’39 shared news of his son skippering a PT boat on D-Day and enclosed a Stars and Stripes story about a later duel with a pair of German minesweepers off the Island of Jersey. Lt. Daniels described the action: “Shells and machine gun bullets whistled around us as both sweepers tried to repel the attack. We took a few hits but handed out more than we took.” Daniel would go on to become a lawyer and civic leader in his hometown of Jacksonville, Fla.

Alumni featured in The Princeton Class of 1942 During World War II, a book published in 2000, include Capt. Arthur P. Adams ’42, an Army Air Corps pilot who flew missions in England and France. His cousin, Thomas Adams, shared a letter that Arthur had written soon after the D-Day invasion: “D-day found us flying our asses off — a matter of shuttling back and forth between our base and the beachheads. Though we’re having our share of action, it’s nothing compared to the hell the ground troops are undergoing.”Adams added that he’d had a total of two days off in the past three months — though he did “manage to hit the sack for a couple of hours” between missions. On July 18, 1944, he was shot down and killed near Chartres.

Perhaps the most poignant PAW story about the Normandy invasion was published six decades later. Victor Brombert, an emeritus professor of French and comparative literature, fled Paris with his family during the German occupation of France and then returned on D-Day, landing with the American Second Armored Division on Omaha Beach. In 2004, Brombert visited Normandy with a group of Princetonians and wrote vividly about both the haunting memories of his wartime experiences and his earlier, happier days vacationing on the same beaches. Below, read the full text of Brombert’s essay, originally published in the Jan. 26, 2005, issue of PAW.

This story was updated to include the class notes entry about the death of James Gerard “Jerry” Schaefer ’40.

Return to Omaha Beach

By Victor Brombert

(From the Jan. 26, 2005, issue of PAW)

Victor Brombert, a scholar of French and comparative literature who chaired the Council of the Humanities, retired from teaching at Princeton in 1999 and wrote a highly regarded memoir, Trains of Thought: Memories of a Stateless Youth (2002). Born in Germany to Russian-Jewish parents, he grew up in Paris but fled to the United States during the German occupation of France. In 1943, Brombert joined the U.S. Army and later landed with the Second Armored Division on Omaha Beach.

I really did not wish to return to Omaha Beach. Once before, in 1984, on our way to a conference center in a small château near Cerisy-la-Salle, my wife suggested we make a slight detour to visit the nearby military cemetery overlooking the beach where I had landed, in June 1944, with Patton’s Second Armored Division, known as “Hell on Wheels.” But our rented car began to emit weird metallic noises that were diagnosed as coming from the gearbox. We barely made it to Cerisy and gave up the idea of visiting the American cemetery at Colleville. I felt relieved.

Why was I so reluctant to return to the place of the D-Day landing? I have asked myself that question many times during the past 60 years. Perhaps I did not wish to celebrate in any way the memory of war. My parents were determined pacifists and made me read anti-militaristic books. Yet they knew that certain wars cannot be avoided, and that this one, against Hitler, had to be fought and won. But it had to be won precisely by those who hated war.

Perhaps I was reluctant to return for fear of being overcome by emotion at the thought of all the young lives that had been cut short. The count of the dead is painful enough; one always forgets to count the many who are maimed for life. Perhaps I also felt some apprehension and distaste at the thought of facing the pious beauty of this cemetery with its planted trees and shrubs, its rose beds, its reflective pool, its manicured lawns, its colonnade and flagpoles. The official booklet boasts of a million visitors who come each year to admire this cemetery which, as the text claims, is “bursting with life.” I know that no memorial can ever tell the truth, and that stones are not alive.

That is why, when I was invited to join a Princeton conference group that was to visit Omaha Beach in June on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the landing, my first reaction was to find excuses for declining. But my wife, Beth, urged me to accept, and I did change my mind. I knew that it was now or never. Sixty years had elapsed since that day in June 1944 when I came ashore on French soil. I was then 20 years old and thrilled to return to the country from which I had escaped during the occupation. But what really changed my mind about the conference invitation, I believe, was hearing more about the program, the good cheer and intellectual stimulation promised by distinguished colleagues, trustees, and alumni who were to participate, the historic and artistic landmarks we were to visit, and the timely topics that were to be discussed under the general theme of Franco-American relations.

To some extent, the title of the conference, “France and the United States: Old Friends, New Perspectives,” had a slightly ironic ring in view of recent events. But there were deeper ironies for me personally. We were guests of Christopher Forbes ’72, a warm-hearted and knowledgeable host, in the Forbes family’s Château de Balleroy, an early masterpiece of the great 17th-century architect François Mansart — an aristocratic pleasure residence where we were treated to sumptuous food at a black-tie dinner and to regal fireworks in the garden. But I was only too aware that the Château de Balleroy stands at the edge of the Cerisy forest, where a few days after the D-Day landings my unit, hiding in the forest, was heavily shelled, and a corporal in the tent next to mine was hit in the head by shrapnel from the much-feared airburst shells.

This sense of irony became even more intense at the military cemetery the following day. The loggias and the colonnade, the huge bronze statue supposedly representing the “Spirit of American Youth” rising from the water, the plinths and steps of granite, the immaculate lawns of Kentucky bluegrass and the crosses of white Italian marble — none of this was related to my memories of the landing. The neatly aligned tombs in fact stood in sharp contrast to the temporary trenches in the sandy ground — more like mass graves — in which the dead soldiers were placed at the time of the battle, wrapped in cotton mattress covers. I was struck by the lush plantings near the dunes and the well-kept paths leading down easily to the beach, giving the impression of a resort atmosphere. There was irony even in the weather on the day our group visited the historic ground of Omaha Beach. It was an ideal late spring day. The shimmering sea had an almost Mediterranean hue, the sky was cloudless, the rays of the sun and the soft breeze felt like an incongruous caress. I remember distinctly that when we landed in 1944 the weather itself was hostile, the light was foul, the landscape livid.

On the bus ride from Château de Balleroy to the cemetery near Omaha Beach, as peaceful-looking Norman farms and fields glided by, I became aware of the discrepancy between the almost festive atmosphere of our excursion and the grim images I associated with the very fields we passed. It had been on just such a field on the plateau above Omaha Beach, that I fell asleep the night after the landing, too tired to dig a hole, and was brutally awakened by a bright flare and the shriek of a Stuka plane as it came diving toward me. Now everything looked bucolic. Most of the Norman-style farmhouses dated from after the war. They had replaced the scenes I remembered: the gutted houses, the collapsed walls, the burning or still-smoldering shambles, the fields filled with dead cows and roads littered with broken-down vehicles and corpses in uniform.

The beach itself, on the day of our visit, was not easy to recognize. Only the grayish pebbles seemed not to have changed. I had remembered the dunes as barren and forbidding. Now, as I looked up, they were covered with green vegetation, the steep slopes thick with vigorous shrubs. Aware of my perplexity, a colleague suggested that the German units might have cut down the vegetation for better visibility. I did not think that was likely. More disturbing still: I could not figure out where exactly our tanks (and my jeep) had made their way up to the bluff and to the village of Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer. There were several winding beach exits, and memory proved tricky.

Other layers of the past complicated the archaeology of remembrance. The beaches of Normandy — the sandy ones, that is: Cabourg, Deauville, Trouville — had been the vacation playgrounds of my childhood and adolescence. In 1933, the year Hitler came to power, I was building sand castles and collecting seashells on the beach of Cabourg, unaware that the big hotel behind me was an important setting in Remembrance of Things Past, Marcel Proust’s novel describing a peaceful vanished world. In 1939, on the other hand, while playing volleyball and falling in love in Deauville, I was perfectly conscious that this summer before the outbreak of the war was fraught from the start with dark omens, a pervasive feeling of inevitable loss, and a sense of an impending calamity. That September, indeed, Hitler invaded Poland, and the war started. Then came the uncanny eight months during which we settled in Normandy to avoid the expected air attacks against Paris, until that day in May 1940, when the Germans launched their blitzkrieg, routing the French army, and we experienced the Nazi occupation and Vichy regime. And then, in the 1970s and 1980s, in a totally different mood, there were the memorable colloquia on Flaubert and Hugo I attended at the conference center of Cerisy-la-Salle — just a few miles away from the Forbes’ Château de Balleroy and the very woods where my “Hell on Wheels” division was shelled after coming ashore. Finally, years later still, there were the many Easters Beth and I celebrated with friends among the apple orchards near Pont-l’Evêque. How could memory be focused, especially when blending so many periods, so many images and sensations?

It took concentration to disentangle and reclaim precise episodes at the time I was writing the war chapters of my memoir, Trains of Thought. I was troubled by the question of honesty. Events and images of events tended to blur. I was not always sure what was preserved over the years — the moment itself or action shots by war photographers I had seen later, and even accounts in books. Scenes from Hollywood films also intruded. Yet I believe that I could relive quite vividly some of the impressions of the landing: the beach littered with debris, overturned landing boats, demolished vehicles, mired trucks, abandoned equipment and ammunitions belts, and the German defense system quite visible with its beach defenses pointing their teeth toward the sea, its V-shaped anti-tank ditches, its pillboxes that had been stormed by our troops. I recall staring at wounded men with large bandages around their heads, with slits for their eyes, sitting dejectedly while waiting to be evacuated. They had watched their comrades being mowed down by machine gun fire as they were wading ashore, and seen others disappear under the surf.

After the landing came the seemingly interminable weeks of fighting in the bocage countryside of Normandy, with its countless hedgerows enclosing small fields with bristly double hedges and treacherous sunken roads. This was perfect terrain for German snipers and hidden machine gun nests to pin down our soldiers on the move. It was a constricting terrain on which our tanks could not deploy. The breakthrough occurred at Saint-Lô, when wave after wave of our bombers made the earth tremble and transformed fields and hamlets into a lunar landscape.

Images of the Saint-Lô breakthrough continue to haunt me. There was hardly an apple orchard or cattle enclosure where one did not come across dead animals and dead men in uniform. Some of these bodies had fallen over each other, lying in what seemed like a fraternal embrace. Other corpses were more ghastly. These men seemed to have been surprised in ordinary activity; they reminded me of human figures mummified by volcanic lava. Still others lay in contorted poses, with one arm raised as though to curse the sky that had poured down such devastation. The most horrific, perhaps, were the corpses of tank drivers and gunners, their bodies folded over the turrets. Others had been finished off by shells as they were trying to crawl out of their tanks. Often they were burned beyond recognition.

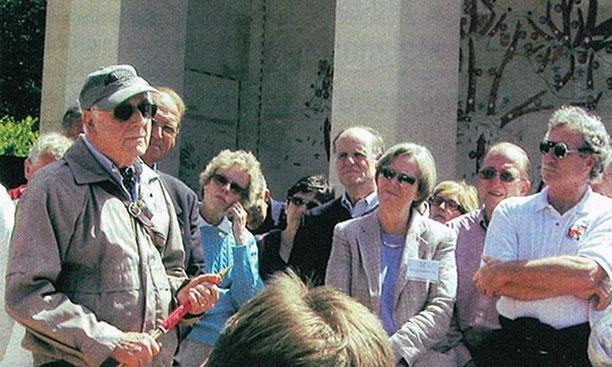

Standing on the pebbles of Omaha Beach last June, holding in my hand one of those pebbles that had been given to me ceremoniously when we arrived at the cemetery, I kept thinking of past fear and trembling, and it occurred to me that soon there would be no more survivors of that landing. It also occurred to me how different a country the United States was at that time, when there was so much good will and common purpose. I felt moved when Christopher Forbes and I laid a Princeton University wreath with orange flowers under the soaring war memorial. (Forbes’ father, Malcom S. Forbes ’41, also came ashore in Normandy.) As happens sometimes, I was also moved by my own words on that occasion, as well as by that moment when I was asked to give President Tilghman a commemorative pebble in honor of her father, who had landed in Normandy as part of the Royal Regiment of Canada.

My feelings were intensified by the indignation with which I had just read in the official booklet a comment made by General Patton a year after the invasion: “It is foolish and wrong to mourn the men who died. Rather we should thank God that such men lived.” That statement seemed to me to illustrate everything that is profoundly wrong about war and warriors.