Freddy Fox goes to war

How a favorite son took his talent for theater to the battlefields of Europe

Three U.S. Army jeeps roared through the small Luxembourg village, just a few miles from the front lines near the German border. It was early September 1944, three months after D-Day. The vehicles in front and back bristled with guards and machine guns. The one in the middle bore the distinctive red license plate of a major general. In the backseat sat a ramrod figure sporting a magnificent military moustache and general’s stars. All three jeeps were clearly identified by their markings as belonging to the 6th Armored Division.

(This is a corrected version of an article published in the March 21, 2012, issue. The correction appears at the end of the story.)

The convoy pulled up to a tavern run by a suspected Nazi collaborator. The general and his lanky, bespectacled aide strode inside. With the help of their bodyguards, they “liberated” six cases of fine wine, loading them onto the general’s jeep. The little convoy then took off, leaving the seething proprietor plenty of incentive to get word to the Germans about what he had just witnessed: that the American 6th Armored was moving in.

But in fact, the whole bit was a carefully choreographed flim-flam. The 6th Armored Division was far away. The commanding presence in the back seat was no general, but a mustachioed major playing king for a day. His dashing young aide was Fred Fox ’39, who later would become known as Princeton’s Keeper of Princetoniana and favorite son. As an undergraduate, Fox had trod the boards in college musicals and dreamed of making it to the big time. Now he found himself playing a leading role in a top-secret piece of performance art designed to help win World War II. And his flair for the dramatic would prove instrumental in its success.

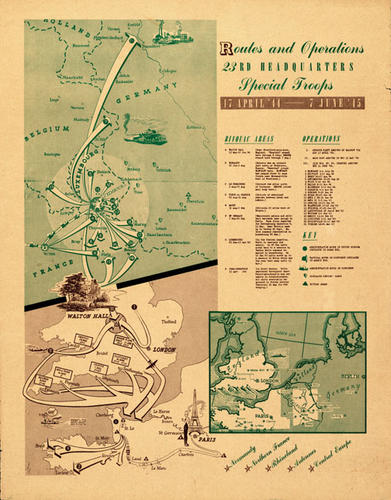

The unit to which Fox was assigned in January 1944 was unique in the history of the U.S. Army. Officially, it was called the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, but eventually it became known as the Ghost Army. Its mission was to stage frontline deceptions designed to dupe Hitler’s legions — and avoid getting killed by the audience while doing so. Instead of artillery and heavy weapons, it was equipped with truckloads of inflatable tanks, a world-class collection of sound-effects records, and a corps of radio operators trained in the art of impersonation. “Its complement was more theatrical than military,” Fox wrote long afterward, in an unpublished manuscript now cherished by his son Donald. “It was like a traveling road show that went up and down the front lines impersonating the real fighting outfits.”

Fox found himself right at home in this high-stakes off-Broadway show. After graduating from Princeton, he had set his sights on Hollywood. “He wanted to be the next Jimmy Stewart,” Donald Fox says. And why not? Like Stewart ’32, Fox had been a star of Triangle Club musicals that played in New York and other East Coast cities to great acclaim. In 1938 he portrayed King Charles II in the show Fol-De-Rol, directed by a young alum starting to make a name for himself on Broadway: José Ferrer ’33.

Upon arriving in Tinseltown, Fox signed on with NBC Radio. But the closest he came to stardom was writing commercials for Clapp’s Baby Foods and editing an in-house newsletter. After Pearl Harbor, he enlisted in the Army and was selected for Officer Candidate School. Fox thought he was leaving showbiz behind, but his stage training soon would prove invaluable on the battlefields of Europe.

“Fred was a Hugh Grant personality,” says Al “Spike” Berry, who served with Fox. “He was very innovative and creative.” He was surrounded by plenty of other creative types, especially the artists handling visual deception. Among the unit’s 1,100 men was a 21-year-old with a perpetual grin from Indiana named Bill Blass, who later became a fashion icon. Art Kane was the Brooklyn kid who later would take a legendary photograph of 57 jazz greats on a stoop in Harlem. Ellsworth Kelly would gain fame as a painter and sculptor. They were just a few of the many artists, recording engineers, and others recruited for the unusual deception mission. Blessed with a sharp wit and a gentle, curious nature, Fox was quick to make friends with many of his fellow deceivers. Together they rehearsed for a dangerous world premiere on the European continent.

Once they landed in France, the men of the 23rd would be expected to conjure up phony convoys and phantom divisions to mislead the enemy about the strength and location of American units. To pull this off, they were equipped with truckloads of inflatable tanks, trucks, artillery, jeeps, and even airplanes — enough to simulate two divisions. Each lightweight dummy could be set up and taken down in about 20 minutes, and from several hundred yards away looked indistinguishable from the real thing. The men also had specially outfitted halftracks, carrying speakers with a range of 15 miles, that could project the sounds of armored columns moving in the darkness. Dozens of radio trucks could create faux networks that sounded utterly like the real thing to eavesdropping enemy officers. In theory, they could impersonate a division of 15,000 soldiers holding a spot in the line, while the fighting division was moving someplace else to launch a surprise attack. But Fox and his fellow performers had no idea if they could put on a show that would prove convincing to their German audience.

On June 6, 1944, nearly 175,000 Americans landed in France in one of the most momentous military operations in history. D-Day found Lt. Fred Fox aboard the troopship John S. Mosby under bombardment from German shore batteries, waiting to go ashore with a 24-man radio platoon. It took several weeks before the entire Ghost Army landed in Normandy and was ready to operate.

In early July, the Ghost Army conducted its first full-scale deception, Operation Elephant. It pretended to be the 2nd Armored Division staying in reserve, while the real unit secretly moved up to join the frontline fighting near the Normandy town of St. Lo. Fox, with his background in theater, was less than impressed with what struck him as a half-hearted embrace of the role. Once the inflatable dummies were set up and the radio networks operating, no thought was given to what else the soldiers might do to make their illusion convincing. In early July, he sat down at his typewriter and pounded out an impassioned critique. “The attitude of the 23rd HQs towards their mission is lopsided,” he wrote in a memo to his superiors, reproduced in a 2002 book by Jonathan Gawne, Ghosts of the ETO: American Tactical Deception Units in the European Theater 1944–1945. “There is too much MILITARY ... and not enough SHOWMANSHIP,” Fox wrote. He believed that the 23rd needed to think of itself less as a strictly by-the-book Army outfit and more as a theater troupe ready to put on a show at a moment’s notice.

Fox decried what he called “bad theater” and argued that, to be truly convincing, the men had to throw themselves into their parts. “The presentations must be done with the greatest accuracy and attention to detail. They will include the proper scenery, props, costumes, principals, extras, dialogue, and sound effects. We must remember that we are playing to a very critical and attentive radio, ground, and aerial audience. They must all be convinced.”

The Ghost Army had gone to France prepared to conduct a multimedia show using three kinds of deception: visual, radio, and sonic. That was not enough, argued Fox, who proposed a fourth type of deception that became known as special effects. It was, in essence, playacting. If they were portraying the 75th Infantry, they should wear 75th Infantry patches on their uniforms, put 75th markings on their trucks, and drive them back and forth through towns. The men should be versed in the details of the 75th so they could talk about it to civilians. There should be a phony headquarters bustling with officers. “Road signs, sentry posts, bumper markings and the host of small details which betray the presence of a unit should be reconnoitered and duplicated with special teams of the 23rd,” Fox wrote.

A blistering memo from a young officer can make or break an Army career. In this case, the higher-ups embraced Fox’s ideas. The memo went out to the entire unit under the name of its commander. Although Fox remained relatively low on the totem poll, Lt. Col. Clifford Simenson, the operations officer, turned to Fox to provide the stagecraft needed to make the special effects come to life.

“Behind every operation was a touch of Fred Fox,” says Spike Berry. Fox took on the role of scriptwriter and director. “Members of the decoy unit were trained to spill phony stories at the local bars and brothels,” Fox recalled in his manuscript, “which didn’t require much training.” Berry remembers that Fox would coach the men before each deception. “He’d get us in a huddle and say, ‘This is what’s going to happen, and this is what we want you to say, and just be natural.’ For example, guys went to the bakery, got some rolls, and said, ‘We’ve got to get an extra supply because we’re moving out tonight,’ that kind of thing.”

Fox was adamant that the soldiers in the unit needed to impersonate generals. “Nothing gives away the location of an important unit quicker than a silver-starred jeep,” he wrote. The fact that such an impersonation was a court-martial offense carried no sway with him. “Is not the whole idea of ‘impersonation’ contrary to (Army regulations)?” he wrote. “Remember we are in the theater business. Impersonation is our racket. If we can’t do a complete job we might as well give up. You can’t portray a woman if bosoms are forbidden.” Once again, the young lieutenant carried the day, and in operations to come, captains and majors in the unit frequently would portray generals. Fox enjoyed playing the part of a general’s aide, but he later wrote that he lived in fear they would run into a real major general and be unable to explain themselves. (The unit was so secret that members couldn’t even tell other Americans what they were doing.)

From June 1944 to March 1945, the Ghost Army ranged across Europe, staging more than 20 full-scale deceptions, each choreographed down to the smallest detail. The men frequently operated within earshot of the front lines, and took casualties when they succeeded too well in drawing enemy fire to their position. Three men were killed and nearly two dozen wounded over the course of the war. In September 1944, they helped hold a critical part of Gen. George Patton’s line along the Moselle River. That December, they barely escaped capture by the Germans in the Battle of the Bulge. In March 1945 the unit executed its most dazzling deception, misleading the Germans about where two American divisions would cross the Rhine River.

This was the Ghost Army’s grand finale, and the men of the 23rd went all out, puffing themselves up to look like 30,000. Radio operators following a minute-by-minute script set the stage, creating the illusion that a convoy was moving to the point of the fake attack. Hundreds of fake tanks were inflated overnight and clustered around farmhouses in the villages of Anrath and Dülken. Enclosed farmyards were turned into phony repair depots, and a grove converted into a decoy motor pool. A phony airstrip complete with dummy aircraft was laid out in a farmer’s field. Sonic trucks projected the sounds of bridge-building all night, as if engineering battalions behind the line were assembling the pontoon structures needed to bridge the Rhine.

On March 24, 1945, with Winston Churchill and Dwight Eisenhower among those looking on, two divisions of the 9th Army crossed the Rhine with few casualties. The 23rd earned a special commendation from the 9th Army commander, Lt. Gen. William Simpson — a glowing review of the final performance of the Ghost Army. By then Fox himself had been promoted to captain, and he would finish the war with a Bronze Star for meritorious service.

As the war wound down, Fox was selected to write the official Army history of the 23rd. He joked that he got the job because of the compelling citations he wrote for other men’s medals, and the volumes of letters he penned to his fiancée, Hannah Putnam, back home. It is safe to say that the resulting document is among the most entertaining unit histories ever written. On page after page of the once-secret but now declassified history, which can be found at the National Archives in College Park, Md., the reader can see the twinkle in Fox’s eye.

On working with inflatable dummies:

Officers who had once commanded 32-ton tanks, felt frustrated and helpless with a battalion of rubber M-4s, 93 pounds fully inflated. The adjustment from man of action to man of wile was most difficult. Few realized at first that one could spend just as much energy pretending to fight as actually fighting.

On the week the unit spent bivouacked just outside a newly liberated Paris:

Paris was put OFF LIMITS and ON LIMITS so often that everyone in confusion visited it whenever possible. It was a great town. The girls looked like delightful dolls, especially when they whizzed past on bicycles with billowing skirts. ... the Parisians were very happy to see us.

Fred’s son Donald says his father was embarrassed that he had such a good time in the Army. But Fox’s war wasn’t just a lighthearted farce. In the days after the D-Day landing, he found himself attached on temporary duty with the 82nd Airborne in Normandy. The disturbing things he witnessed put him in closer touch with his own budding pacifism. “The company was too rough for me,” he wrote home. “I did get some more strong antiwar material — especially from boys who had just killed Germans or were just going out to kill some more.”

On June 10, 1944, he wrote, he was reading in his jeep, waiting for the troops to move out when he smelled a pot of coffee being brewed by some paratroopers. He headed over to see if he could get some. Then he noticed two American soldiers working over a smoldering staff car with the bodies of two German officers inside. The paratroopers were using their commando knives to gouge gold fillings out of the corpses’ teeth.

That was the moment he decided to become a minister.

Years later he wrote about the meaning it held for him: “There is hope for the world if Churchmen would leave their storybooks and climb out of their jeeps. Fires have to be put out and men — even enemies — treated as human beings.”

Fox married Hannah Putnam in July 1945, eight days after the Ghost Army returned home. That September the unit was disbanded. “Its ashes were to be placed in a small Ming urn and eventually tossed into the China Sea,” wrote Fox playfully in the closing paragraph of the unit history.

By 1949, Fox was an ordained minister for the First Congregational Church in Wauseon, Ohio. Itching to write for a wider audience, he contacted the War Department to see if the top-secret story of the Ghost Army could be told. The Army informed him in a memo that “much of the material is still confidential or secret.” Fox turned to other topics instead. He became a prolific contributor to The New York Times Magazine and other publications, a “reverend reporter,” in the words of his son. Upon the 10th anniversary of the Battle of the Bulge, he wrote a Times article that lightly touched on his unit’s deception without divulging too many details. “It reminded me of a production by Cecil B. DeMille,” he wrote, “only we had fewer extras to carry spears.” One of his articles caught someone’s eye at the White House, which led to four years as an aide to President Dwight Eisenhower. But he never forgot about telling the tale of the Ghost Army.

In 1967, by then Princeton’s recording secretary, Fox made another attempt to get the official history declassified, enlisting former Secretary of the Army Stephen Ailes ’33 to help in the effort. Still, he failed. Fox never got to tell the full story, which wasn’t made public until after his death in 1981. It remains largely unknown today.

Fox seemed more amused than impressed with his unit’s wartime exploits. “I think we have traveled more and done less than any other unit” in the European Theater, he wrote Hannah after the war. While there certainly was a touch of the absurd to the whole venture, an Army analysis 30 years later was far more positive. “Rarely, if ever, has there been a group of such a few men which had so great an influence on the outcome of a major military campaign,” wrote Mark Kronman in a report available through the U.S. Army Center of Military History. One of Fox’s fellow deceivers, John Jarvie, who went on to work as an art director at Fairchild Publications and is now retired, put it a different way in 2006: “You know you saved lives. You don’t know how many you saved, but you know you saved them.”

A significant part of the credit for that belongs to Fred Fox. “He was, in my view, maybe the most significant person in the entire 23rd Headquarters Special Troops,” said Bob Conrad, who served alongside him and died in 2010. Fox was, after all, the experienced thespian who gave the show the few daubs of greasepaint and the showbiz spark needed to make it ready for the big time.

Rick Beyer is the author of The Greatest Stories Never Told series of history books, and is making a documentary film about the Ghost Army. Learn more at www.ghostarmy.org.

For the record

The original version of this story misstated the length of time between D-Day and a Ghost Army operation in September 1944.

4 Responses

Richard G. Rebh ’76

2 Years AgoCongressional Honor for Veterans of the Ghost Army

Referencing your March 21, 2012, article “Freddy Fox Goes to War,” I was aware of Freddy Fox ’39 at Princeton through the Princeton University Band, where I was the photographer one year (through my roommate, drum major Bill Jerome ’76), because Freddy supported it — like all things Princeton — with great enthusiasm. I showed the PAW article to my dad, who as a new West Point graduate had commanded the combat engineers of the Ghost Army (one of four field units) and been sworn to silence for 50 years, only talking about it in the late 1990s. He said, “Sure, I’d met with Fred when I reported to headquarters. Great guy.”

Fast forward to March 21, 2024, when the Ghost Army will receive a Congressional Gold Medal for distinguished contributions to the nation in a ceremony at the Capitol. Only 184 such medals have been voted by Congress since the Revolution, and about 10 World War II units have been so honored. Rick Beyer, who wrote the PAW article, led the charge to recognize the Ghost Army’s contribution to victory in the European theater. I’ll be at the ceremony representing my dad — and Freddy.

Editor’s note: The U.S. Army’s 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, aka the Ghost Army, used inflatable tanks, sound effects, false radio communications, and other stagecraft to deceive German troops in the months following the D-Day invasion. This issue went to press before the March 21 ceremony at the Capitol.

Broadus Bailey Jr. ’51

10 Years AgoFox and the Ghost Army

What a delight to read about Fred Fox ’39 (cover story, March 21). I heard of him as an undergraduate and later from a member of the 1981 football team — Fox was evidently an enthusiastic football supporter and attended every practice.

The exploits of the “Ghost Army” were fascinating — and what a shame to have kept the story classified for so long. I seem to remember that there was another ghost army in the United Kingdom before the Normandy invasion — commanded by Gen. George Patton, who was very much afraid that was to be his only contribution to the invasion of Europe!

There is one “infidelity” (as “Buzzer” Hall once commented about my senior thesis) in the discussion of the three jeeps. The major general is unlikely to have ridden in the rear seat of the jeep. The senior officer in a jeep, then and now, rides in the front seat, beside the driver.

We have a senior historian of the Defense Department living in our retirement community, and I will pass this PAW along to him. I am sure he will enjoy it as much as I did. Many thanks, and keep up the good work.

Jay Cady ’78

10 Years AgoAnother Fred Fox tale

Reading about Fred Fox ’39 and the Ghost Army (cover story, March 21) gave me perspective about the time I met Fred in 1976 in his capacity as Keeper of Princetoniana. My roommate, Mark Schaeffer ’78, had founded the Princeton Mime Company, and I was publicizing its first show. I arranged to meet Fred, and asked him if there was any history of students performing mime on campus.

He thought for a minute and said, “How about this. Let’s say that Jimmy Stewart had laryngitis one night and had to perform his part in the Triangle Show in mime.” Taken aback, I asked, “Did that really happen?” Fred replied, “No, but if you tell people that I said it happened, they will believe you.”

Our youthful idealism kept us from using Fred’s fabrication, but reading about how he duped Hitler makes me understand why he had no qualms about a little white lie to help a fledgling student theater company.

Anonymous

10 Years AgoBUZZ BOX: Ghost Army tale sparks fond Fox recollections

The March 21 cover story on Fred Fox ’39’s role in the Ghost Army unit of World War II drew appreciative comments from readers at PAW Online.

“Another feather in Freddie Fox’s much-festooned Tiger hat,” wrote KERRY BROWN ’74.

“For alumni of a certain age, it is virtually incomprehensible that there could be generations of Princetonians whose lives have not been blessed with an exposure to Fred E. Fox ’39,” said JAN KUBIK ’70, citing Fox as “a consummate Princetonian and Keeper of Traditions.”

“What a fabulous story to add to our recollections of the day in June, 40 years ago, when Freddie Fox married my husband Phillip and me in the Princeton Chapel,” wrote KATHRYN WILLIS WOLFE *77. “We still remember him whispering, ‘We foxes and wolves get along well together!’ just to put everyone at ease.”

BOB DAHL ’78 added: “I’d love to see Princeton host the Ghost Army exhibit during Alumni Day or Reunions!”