No genre of American music has been more romanticized than the blues. As with most things that are romanticized, though, the treatment elides and airbrushes many inconvenient truths.

To pick from dozens of arresting examples in Whose Blues? Facing Up to Race and the Future of the Music (University of North Carolina Press), a new book by Adam Gussow ’79 *00, even in its heyday during the Great Migration of the 1920s and ’30s, the rawest Deep South blues artists — guitarists like Charley Patton and Son House — received much less favor from the Black record-buying public, North and South, than did Bessie Smith, Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, and other female blues queens who fronted jazzier, horn-driven ensembles.

Gussow, a professor of English and Southern studies at the University of Mississippi and author of five books on the blues, examines the history and culture of blues music in 12 chapters, which he calls “bars,” to mimic the signature 12-bar blues structure. He traces the genre’s origins (the blues may have originated in the Ohio River Valley, not Mississippi); its impact on Black literature in the works of Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, and others; efforts beginning in the 1990s to reclaim the blues as Black music; and the current state of affairs, which is muddied. According to Gussow, the top contemporary blues performers include Ken “Sugar Brown” Kawashima, a Japanese American, and Aki Kumar, an Indian immigrant who sometimes sings in Hindi.

“Adam has been a careful and devoted scholar of blues studies for some time now,” says former Princeton professor Daphne Brooks, now a professor of African American studies at Yale, who has also addressed racial and gender tensions in the blues in her work. “We ought to be able to identify how the blues is forever deeply extricated with its history, but that doesn’t mean that it hasn’t had a transformative impact on modern life. We should take seriously the extent to which Adam’s study calls attention to the obscuring of that history.”

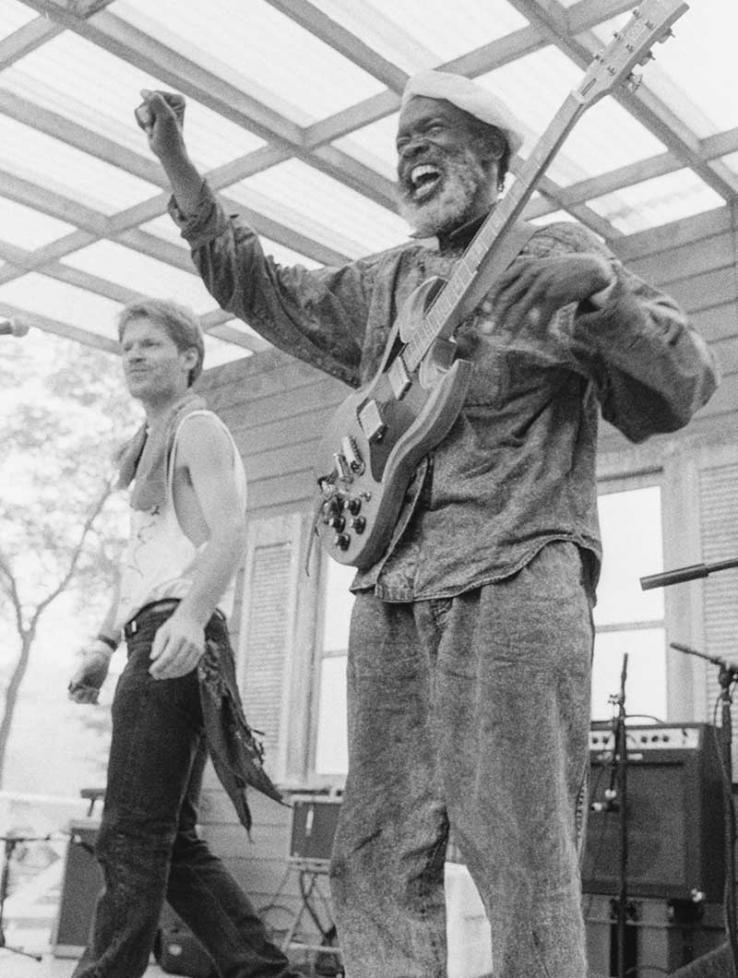

The subject is more than academic for Gussow, who personally stands astride the music’s racial divide. A highly regarded blues harmonica player, Gussow partnered for years with Sterling “Mr. Satan” Magee in the duo Satan & Adam, playing on the streets of Harlem. (Magee died Sept. 6, 2020, after contracting COVID-19.) Like many white blues players, Gussow notes that he apprenticed under two great Black musicians — in his case, Magee and Nat Riddles. Now he is a mentor to several young Black proteges.

At its heart, Whose Blues? addresses a much larger question, one which echoes throughout Black history and popular culture: Who “owns” the blues? Who performs it, curates it, defines it, interprets it — and, perhaps most significantly, makes money off it? In the following excerpt, Gussow defines the two main currents of thought in the contemporary blues world. With a foot in both camps, Gussow refuses to commit himself to either.

“My goal,” he writes, “is to spoil the party for everybody concerned.”

Starting the Conversation

By Adam Gussow ’79 *00

Speaking very broadly, people who have emotional investments in the blues — people who like, play, think about, talk about, and identify themselves with the blues — have two diametrically opposed ways of configuring the blues in ideological terms. An ideology is simply an idea-set: an intellectual orientation that governs the way one sees the world and thinks through the problems it presents. One way of ideologizing the blues is to say, “The blues are black music.” They’re a black thing. When you look at the history and cultural origins of the blues, when you look at who has a right to claim the social pain expressed through the blues — what you might call the “I’ve got the blues” element of the blues — and when you look at who the most powerful performers and great stylistic innovators have been, it’s black people who have a profound, undeniable, and inalienable claim on blues in a way that whites just don’t. The history, the feelings, the music: They’re a black thing. And when whites get involved, as they always do, black people suffer.

This ideological position, a form of black cultural nationalism that I term “black bluesism,” is expressed with great clarity and power by Roland L. Freeman, an African American photographer and cultural documentarian, in a poem titled “Don’t Forget the Blues.” Freeman composed his poem in 1997 to mark the twentieth anniversary of the Mississippi Delta Blues and Heritage Festival — the oldest black-run blues festival in the country — and he read it out loud to the crowd. “Do you see ’em,” the poem begins, “here they come”:

Easing into our communities

In their big fancy cars,

Looking like alien carpetbaggers

Straight from Mars.

They slide in from the East,

North, South and West,

And when they leave,

You can bet they’ve taken the best.

Listen to me,

I’ve been drunk a long time

And I’m still drinking.

I take a bath every Saturday night,

But I’m still stinking.

This world’s been whipping me upside my head,

But it hasn’t stopped me from thinking.

I know they’ve been doing anything they choose,

I just want ’em to keep their darn hands off ’a my blues.

That aggrieved “I,” demanding our attention, is an avatar of the blues, his blackness unmarked but evident, who refuses to say die: Drunk and stinking, beaten down by the world, he is still “thinking,” still conscious and resistant. The poem’s omnipresent “they” is white people — more specifically, white blues tourists, fans, producers, musicians, anybody who seeks pleasure and profit from the music. “They” is the oppressive white world, an all-points barrage (“from the East / North, South and West”) that surrounds, exploits, and unmakes black people (“us”) and their (“our”) world, body and soul. Playwright August Wilson evokes both worlds in his “Preface to Three Plays” (1991) when he talks about how the blues gave him “a world that contained my image, a world at once rich and varied, marked and marking, brutal and beautiful, and at crucial odds with the larger world that contained it and preyed and pressed it from every conceivable angle.”

Like Wilson, Freeman sees the blues as an art form that contains an image of his humanity, but, unlike Wilson, he sees the blues themselves as something that the white world has purloined and profited from, an expropriation anticipated by the earlier refashioning of rhythm ’n’ blues into rock ’n’ roll. “How can we stop ’em,” he cries as the poem rolls on, “or will it ever end?”:

Mama’s in the kitchen

Humming her mournful song.

Sister’s moaning in the bedroom,

Crying some man has done her wrong.

Papa’s in the backyard sipping on his corn-n-n-n . . . liquor,

He’s just screaming, hollering and yelling.

And the old folks on the front porch keep saying,

“There just ain’t no telling

How long it’ll take ’em to leave us alone.”

They have taken our blues and gone.

“Don’t Forget the Blues” speaks to the blues from a beleaguered black nationalist perspective. At the heart of the poem is a contemporary black folk community in crisis. There’s mama, there’s sister, there’s papa and the old folks, and there’s the poet himself; the family is a microcosm for Black America, and everybody is hurting. Freeman’s black family has the blues at the very moment when the surrounding white world is consuming and capitalizing on the blues. That white world, these days, is populated by self-styled blues aficionados who claim to love the music and who shout things like, “Keep the blues alive! Let’s drive on down to Clarksdale, Mississippi, and listen to the real blues at Red’s Lounge! Let’s pay five thousand dollars and take a blues cruise to the Bahamas! Let’s fly our Dutch blues band to Memphis and compete in the International Blues Challenge.” Freeman’s poem articulates the pain created by the juxtaposition of, and the power differential between, two radically different blues worlds: an immiserated but tightly knit black community on the one hand and, on the other, a widely dispersed mainstream blues scene that takes pleasure and profit from the music. When Freeman cries, “There they go, with our gold,” he is, at least implicitly and with prophetic foresight, taking aim at my viewers, my customers, and me — millions of blues harmonica players from 192 countries and territories around the world who enjoy the hundreds of free instructional videos I’ve uploaded to YouTube since 2007, a modest percentage of whom visit my website every year and sometimes buy my stuff.

Freeman’s poem articulates the pain created by the juxtaposition of, and the power differential between, two radically different blues worlds: an immiserated but tightly knit black community on the one hand and, on the other, a widely dispersed mainstream blues scene that takes pleasure and profit from the music.

Freeman’s poem speaks, in other words, to the transformations that mark our contemporary blues moment, even though it was composed in 1997, before the full extent of those transformations had become evident. It evokes the alarm felt by one particular black community advocate at the fact that blues music has moved outward from his community into the larger world, even while black people in those communities are still suffering, still hurting. Black people still have the blues. Young black kids may not particularly like or play blues music. But they and the old folks still have the blues. And something vitally important is being lost, Freeman’s poem insists, as blues music floods outward into that surrounding (white) world. Not just lost: Something is being taken away from black people in an old, familiar, hurtful way. “I know they’ve been doing anything they choose,” he says repeatedly. “I just want them to keep their darn hands off of my blues.”

The black bluesist vision certainly has its virtues. But it is confronted, in any case, by a second and diametrically opposed way of ideologizing the blues, one that holds somewhat more sway in our contemporary moment, at least among denizens of the mainstream scene. I’ll call this second orientation “blues universalism.” The epitome of blues universalism is a phrase — a T-shirt meme — that the Mississippi Development Tourism Authority has put up in the waiting rooms of the welcome centers as you enter Mississippi: “No black. No white. Just the blues.”

As problematic as that phrase is, I understand and appreciate the anti-racist message that it believes it is conveying. One nation under the sign of the blues! No segregation, no overt disrespect, no “If you’re black, stay back.” All that race-madness is behind us now. Blues can be a place — or so the slogan suggests — where blacks and whites and, by implication, a whole bunch of different people, come together. Gay and straight. Men and women. Working-class and middle-class. Americans and foreigners. That’s a good thing, right? Certainly it is a huge improvement over the bad old Mississippi of the Jim Crow era, a place known over the years as “the lynching state” and “the closed society,” where blues got no respect whatsoever from white people. Now, an irritable black bluesist might point out that since an overwhelming majority of the greatest Mississippi blues performers, historically speaking, have been African American, and since Mississippi’s contemporary blues tourism industry is anchored in the reputations of those celebrated performers, there’s something disingenuous about welcoming blues tourists to your state with a slogan like “No black. No white. Just the blues.” Doesn’t that formulation tend to underplay the hugely disproportionate black contribution to the blues — the very reason, in fact, why so many white blues tourists flock to Mississippi in the first place? Wouldn’t a phrase like “Welcome, white blues tourist, to the home of real black blues” be more accurate? But at least the welcome mat has been thrown out, and at least Mississippi’s blues are being celebrated in Mississippi. That’s a good thing, isn’t it?

A black bluesist might point out that since an overwhelming majority of the greatest Mississippi blues performers, historically speaking, have been African American, and since Mississippi’s contemporary blues tourism industry is anchored in the reputations of those celebrated performers, there’s something disingenuous about welcoming blues tourists to your state with a slogan like “No black. No white. Just the blues.”

Why do so many different kinds of people around the world not only listen to blues but sing and play the music? Why is it so receptive to their embrace, so adaptable to infusions of local flavor, even while maintaining its identity as blues? Perhaps the music’s distant African origins offer a clue. Many enslaved Africans in the antebellum South, especially in Louisiana, were brought from Senegal and Gambia. One thing that made that part of West Africa distinctive was the trade routes: a lot of Arab traders coming through, bringing along their Islamic religion and its melismatic vocal music. Melisma is a vocal technique that takes one word or cry and runs it through a long series of pitches; it often takes the form of what ethnomusicologists call a “descending vocal strain.” Melismatic singing — also known as “riffing” in black cultural contexts — lies at the heart of the blues tradition, and black popular and religious music more generally. Field hollers are melismatic. B. B. King is a wonderfully evocative blues singer because he brought gospel melisma into the blues. In other words, one core element of the blues isn’t African per se but Arabic: This is the argument made by German ethnomusicologist Gerhard Kubik in Africa and the Blues (1999). Senegalese musical culture made a space for Islamic melisma, absorbing and transforming that influence even while maintaining its core values. People who live on trade routes need to be quick on their feet, culturally speaking: taking what they like and mixing it into the local stew, even while maintaining that stew’s brand identity. Senegalese culture, in turn, became the generative matrix of blues culture after the crucible of slavery brought Senegalese musicians to the southern United States.

One way of appreciating why Freeman might have felt the need to write his angry poem is to engage in a thought experiment that I call flipping the script. What would the present situation involving whites, blacks, and the blues look like if we picked a “white” folk music — bluegrass, say, rather than blues — and flip-flopped the races, so that blacks, suddenly an overwhelming numerical majority, were the larger world, in August Wilson’s terms, that preyed and pressed on a beleaguered “white” folk-musical community from every conceivable angle? What would that situation look like? It’s a fanciful scenario, one that traffics in stereotypes and exaggerations in order to make a point, but I’d like to play it out, much the way that African American author George Schuyler envisioned the chaos wrought on America by a drug that could turn black people white overnight in his satirical novel, Black No More (1931).

Imagine that you’ve got not just black Americans but also musicians and fans from all parts of Africa, trekking up to the mountains of Kentucky, wanting to hang out with bluegrass banjoist Ralph Stanley, Man of Constant Sorrow. This isn’t Jon Spencer and a bunch of white punk rockers hanging out with bluesman R. L. Burnside in Mississippi, this is Jamal and Dewayne and Ibrahima heading up into the hills and hollers to hang out with Ralph — and Imani and Jada, too, all of them wanting to party with, and document, the mountain man. Imagine that over a fifty-year period, the situation had evolved from a few black folklorists and fans tracking down Ralph, Bill Monroe, and Flatt & Scruggs, to a situation in which hundreds of thousands of black kids are buying banjos, guitars, fiddles, and learning how to play bluegrass, to a point where now, at this late moment, black people actually have a monopoly, or near monopoly, on the means of production. The record labels — Motown and Death Row Records — are up in the hills. They’re doing field recordings of Ralph Stanley and his family, and the hardcore black bluegrass aficionados are publishing a magazine called Keeping the Mountains Real. It’s the analogue to Living Blues, but instead of being written and published by whites, with lots of blues album reviews by white reviewers, it’s written and published by an all-black staff, with lots of bluegrass reviews by black reviewers. Keeping the Mountains Real has a certain number of white subscribers; a handful of them even come from the Kentucky hills. But most subscribers are black urbanites, and, as aficionados, they engage in fierce debates about the music they love. Some of them, the “purists,” argue that black bluegrass players just can’t sing bluegrass with an authentic twang; this invariably produces cries of outrage from another cohort of black bluegrass lovers and performers who insist that it’s not about color, it’s about the high lonesome feeling in your heart. They’ve got a slogan: “No white or black, just some bomb-ass ’grass.”

The contemporary situation of the blues, as evoked by Freeman, is sort of like that. Of course this little thought experiment has an element of fun-house exaggeration, but only enough to make a point: Something weird and unsettling has happened to the blues — at least when viewed from a certain kind of skeptical black community perspective.

If I’m a member of a troubled, unsettled blues community — a white-and-black community, a world community — I want to understand where we are as a community.

I’ve already suggested a way I find myself, as purveyor of a popular blues harmonica instructional website, ethically implicated in the present discussion. But I’m interested in having the conversation for a different reason: As the interracially married father of a black/biracial son, I dwell in a family circle where there is no racial “they.” There is only “we.” At the age of thirteen, Shaun’s musical talents have already made themselves vividly obvious — he plays trumpet and half a dozen other instruments — and I’ve taught him the rudiments of blues tonality, along with the heads for “Watermelon Man” and “Doozy.” At some point in the future, if he realizes his promise, it is entirely possible that he will be able to tell an interviewer that he learned to play the blues from an old white man down in Mississippi. The marvelous absurdity of that statement makes me want to think these issues through. If I’m a member of a troubled, unsettled blues community — a white-and-black community, a world community — I want to understand where we are as a community. I don’t see Freeman, with his black nationalist perspective, as a “they” who is stirring up trouble but as a member of my extended family, as it were, who is doing his best to speak the truth as he sees it. If there’s no black and no white, just the blues, then I want to understand where we, as blues people, really are at this moment in history.

Adam Gussow ’79 *00 is a professor of English and Southern studies at the University of Mississippi.

For the Record

The introduction to “Black and White and the Blues,” in the March issue, significantly understated the historical appeal of blues music among the record-buying public. Female blues queens who fronted jazzier horn-driven ensembles, such as Mamie Smith, Bessie Smith, and Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, were so popular, in fact, that their recordings inaugurated a blues craze, beginning in 1920. The introduction has been revised in this version.