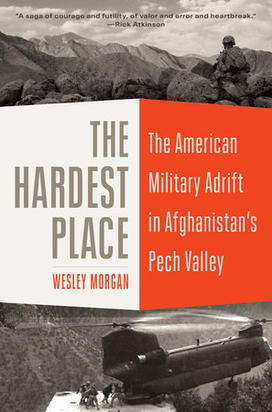

Wesley Morgan ’11 Unravels History and Future of the U.S. in Afghanistan

The book: The Hardest Place: The American Military Adrift in Afghanistan’s Pech Valley (Random House) narrows in on a small, remote area of Afghanistan at the heart of the war on terror occupied by the United States. The book began as a Princeton senior thesis in 2010, after Morgan spent the summer before senior year embedded as a freelance journalist with U.S. troops. Morgan, through hundreds of interviews with Americans and Afghans in the area, discusses the drawn-out history of the U.S. presence in Afghanistan, failed missions, manhunts, and the lives of the soldiers he encountered. While the war in the East is continually changing with new technology, four different presidential administrations, and more, something remains constant: The war will continue to drag on so long as we keep with the status quo.

The author: Wesley Morgan ’11 is a military affairs reporter who most recently covered the Pentagon for two and a half years at Politico. He previously worked as a freelance journalist in Washington, D.C., Iraq, and Afghanistan, contributing stories to The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Atlantic and other publications.

Opening lines: As Lt. Col. Christopher Cavoli stood among the conifers on the eastern slope of the Abbas Ghar, with the Korengal valley over the ridge and the Shuryak behind and below him, he could hear the sobs over the radio of the first of many men his soldiers would kill.

It was April 10, 2006, day one of Operation Mountain Lion—the largest offensive in northeastern Afghanistan since 2003, the first big mission for Cavoli’s 1-32 Infantry battalion, and the start of an ambitious new phase in America’s war in the Pech. From here on out, the Pech and its side valleys would be the day-in, day-out focus and home not just of a Special Forces A-team or a few dozen Marines but of the bulk of a 700-man battalion.

A cerebral 41-year-old with two Ivy League degrees, Chris Cavoli had been waiting for his turn to fight in Afghanistan since September 11, 2001, when, as a major working at the Pentagon, he had spent the day helping man the main triage point outside the smoking building. He had spent his summers as a boy climbing and skiing around the village in the Italian Alps where his father’s family lived, and he relished each day he spent in the mountains; Kunar was no exception. But the hike up the Abbas Ghar was a grueling shock for soldiers who, despite the “Mountain” tabs above their 10th Mountain Division shoulder patches, had trained in the cold flatness of upstate New York.

Cavoli and his men had driven up the Shuryak in pickup trucks as far as the road went. Now they had a day and a half to ascend the Abbas Ghar before the main phase of Mountain Lion began and helicopters started delivering hundreds more troops onto the heights around the Korengal. The soldiers were wearing gray camouflage fatigues, which, far from helping them blend in, stood out brightly against the greens and browns of the mountain. On the slopes of neighboring ridges, insurgent spotters were tracking their slow ascent and comparing notes over the walkie-talkies that were essential gear for guerrillas and goatherds alike in Kunar.

The Americans’ Afghan interpreters were listening in, and when one spotter revealed his location, Cavoli encouraged his fire-support officer to call for help from the battalion mortarmen waiting down on the Pech road. The interpreters gave a blow-by-blow as the spotter reported in to his comrades.

“I’m behind a rock,” the invisible man reported after the first salvo missed him. “I’m safe.”

The next group of shells were white phosphorous rounds, packed with a waxy pale chemical that produced billowing white smoke. Troops in the Pech had been pairing high-explosive rounds with white phosphorous ones for months, using the harsh clouds from the WP shells to smoke enemy fighters out of their caves and crevices and into the open where the standard high-explosive shells could kill them.

On the radio, the spotter’s tone changed from fearful to despairing as shells peppered his patch of mountainside. “I can’t breathe,” he gasped. “I must move.” Wounded in the barrage, he died as Cavoli’s soldiers, amped up by their first contact with the enemy, listened in.

Cavoli and his men spent that night in the mountainside before continuing their ascent. Struggling up the steep slope, sometimes hoisting themselves up by hanging on to exposed tree roots, the soldiers of the 1-32 Infantry battalion were getting their first taste of the unforgiving, usually low-tech war that would be theirs for the rest of a deployment that would run 16 months, almost three times as long as any other American troops had spent in the Pech. Facing an enemy who didn’t wear body armor or other heavy gear and was expert at vanishing into the trees and the folds of the mountains, Cavoli’s soldiers often felt as if they spent their days locked in firefights not with people but with rocks and cliffs. For all the U.S. military’s technological prowess, the grinding day-to-day combat would be more like something out of Korea (where 1-32 Infantry had earned the nickname “Chosin” during the vicious December 1950 battle at the frozen Chosin Reservoir) than the higher-tech war that the American public expected. The key weapons available to Cavoli’s soldiers were not drones or smart bombs but machine guns, mortars, and artillery.

The waves of helicopters came the next night, ferrying hundreds of 10th Mountain soldiers and Marines—along with troops from the infant Afghan National Army—into clearings along the Abbas Ghar and in the higher mountains to the Korengal’s south. Over the next few weeks, the plan went, the Chosin battalion and the other troops involved in Mountain Lion would scour the Korengal and leave behind a small outpost there, manned jointly by American and Afghan soldiers, which would become the center of a new counterinsurgency “ink blot” and deny militants like the Egyptian al-Qaida operative Abu Ikhlas al-Masri the use of the Korengal as a safe haven.

The first gunshots to ring out on night two were some harassing rounds aimed in the direction of the snow-coated Sawtalo Sar summit, where Col. John “Mick” Nicholson, Cavoli’s superior, had set up a hasty command post. The rest of the night was quiet as the troops deposited in the mountain landing zones prepared to descend into the Korengal.

“I think they’re hiding,” Nicholson told a journalist who had flown in with his soldiers. “They think this is like other operations where we come in for three or four days. This will be different.”

The two officers made an odd-looking pair—Cavoli five feet six, his round, expressive face topped by a balding crown; Nicholson gaunter, much taller, with a brush of silver hair that looked dignified even in crew-cut form. Nicholson had an almost aristocratic bearing befitting a former first captain of his West Point class, and his manner of speech was polished and succinct. Cavoli talked in sentences so long and complex (and often studded with profanity) that they sometimes struggled to hold the multilayered ideas he was trying to express.

There were similarities too. Both men were Army brats. Both had attended elite universities: Nicholson had left West Point for Georgetown, intending to take premed classes there, only to change his mind and go back to the military academy after earning his civilian bachelor’s degree; Cavoli had done ROTC at Princeton and later earned a master’s degree at Yale. And Afghanistan was each man’s second war—Nicholson’s first had been Grenada in 1983, Cavoli’s Iraq in 1991—but a war to which they were already connected by virtue of where they had been on September 11. Like Cavoli, Nicholson had been working at the Pentagon at the time; when American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the building’s northwest side, it destroyed Nicholson’s office on a day when he happened to be out moving into a new house.

Headed for a forgotten and foundering war, Nicholson had attempted to impose direction onto his brigade’s deployment in the weeks preceding it. With more than a dozen Afghan provinces to cover, the brigade would have to concentrate somewhere, and he chose to plunge into Kunar and Nuristan, starting with the Korengal during April 2006’s Operation Mountain Lion and then leapfrogging north into Nuristan, building new outposts as they went.

Kunar and Nuristan were where Nicholson felt his soldiers could make a difference. In the other hot spot he considered, farther south in Paktika and Khost, the Taliban-led insurgency’s base areas were inside Pakistan and therefore untouchable. (A huge militia force answering to the CIA also guarded the border there.) In Kunar, the Korengal presented a promising target for action on the right side of the border, where his troops could build a new outpost and a new ink blot.

There was another dimension to the decision too. Some rank-and-file troops who flew into the Korengal for Mountain Lion were under the impression that al-Qaida operatives had planned the September 11 attacks there, or somewhere nearby. That wasn’t true, but it was a distortion of a real consideration that played heavily into Nicholson’s and Cavoli’s planning. Of all the provinces in eastern Afghanistan, Kunar and Nuristan were the two where the U.S. intelligence community believed al-Qaida maintained the most regular presence, and they bordered a region of Pakistan that the CIA suspected was the hideout of the top al-Qaida leaders whose trail had gone cold four years earlier.

That was of self-evident importance to officers who had witnessed the destruction of September 11. Both men knew the rough outlines of the intelligence about Osama bin Laden’s suspected escape route from Tora Bora that had pulled special operations forces to Kunar and Nuristan in 2002 and 2003, and had been briefed about Abu Ikhlas, the main al-Qaida figure the military and intelligence community were aware of in Afghanistan. Years later, evidence would emerge that al-Qaida advisers were working quietly with Afghan guerrillas in other parts of eastern Afghanistan at the time too, not just in the two provinces the 10th Mountain leaders zeroed in on. But the intelligence available to military commanders like Nicholson and Cavoli at the time didn’t reflect that; it highlighted Abu Ikhlas, with his higher profile and long history in Kunar.

“Our purpose as a nation for being in Afghanistan in the first place was al-Qaida and terrorist organizations, and the only place in all of Regional Command East that had a known al-Qaida operative was Kunar, where Abu Ikhlas was,” remembered Nicholson.

The CIA played a role in aiming the 10th Mountain Division toward the Pech, too, affirming to division officers visiting Washington before their deployment that Kunar was a good place to go to fight enemies connected to al-Qaida. More than that, it was the gateway to Nuristan, and a heavier U.S. military presence in both provinces might create opportunities for the CIA to recruit new sources in the parts of Pakistan they bordered—Chitral and Bajaur Districts, which there were indications that it might be a hub of upper-level al-Qaida activity. Some in the intelligence community also believed that after his 2002 stint in Kunar, bin Laden had moved there; at Langley, a team of analysts was poring over imagery from potential compounds in Chitral “square yard by square yard,” according to a former senior intelligence officer, looking for clues.

New military offensives on the Afghan side of the border could push militants around and force them to talk to their leaders back in Pakistan, where the NSA was intercepting more communications than ever. And new outposts in remote Nuristani districts could create new opportunities for case officers to recruit local agents, like smugglers or merchants, who spent time in the Pakistani districts the intelligence agencies were interested in.

“Our interest in Kunar was as a means to an end,” said paramilitary officer Ron Moeller, the CIA’s liaison to 10th Mountain. “We gave lip service to Kunar because the conventional forces wouldn’t expand into Nuristan until after Kunar and the Pech. Mountain Lion became this convenient foundation.”

“We weren’t that interested in people in Afghanistan, but you had to develop source networks aimed to the east,” in Pakistan, added another CIA officer who was in Afghanistan at the time. “Everyone believed that bin Laden would be in Chitral or Bajaur, but we couldn’t set up bases there. The closest place the military could set up bases was in Kunar and Nuristan.”

The theory was misguided, at least partly. Bin Laden wasn’t in Bajaur or Chitral; he was already living in Abbottabad, in Pakistan’s developed interior. As in the fall of 2003, top-level pressure to pick up bin Laden’s trail was causing U.S. intelligence to look in the right direction too late and helping draw American troops there as a result. This time it wouldn’t be a few small special operations teams that stayed behind after the offensive but the bulk of Cavoli’s Chosin battalion: hundreds of soldiers, enough to dot the Pech with many new ink blots.

Review: “The definitive account of America’s heroic but ultimately doomed effort in one of Afghanistan’s most rugged regions.”—Sebastian Junger, author of Tribe

Reprinted from THE HARDEST PLACE: The American Military Adrift in Afghanistan’s Pech Valley Copyright © 2021 by Wesley Morgan. Published by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC

1 Response

Byron Gillory

4 Years AgoMoving and Powerful Book

Your book The Hardest Place was great. Very moving and powerful. Really enjoyed it on audiobooks and purchased a copy as well. I have listened to 26 books on the war on terror. Yours is one of the best!

Thank you,