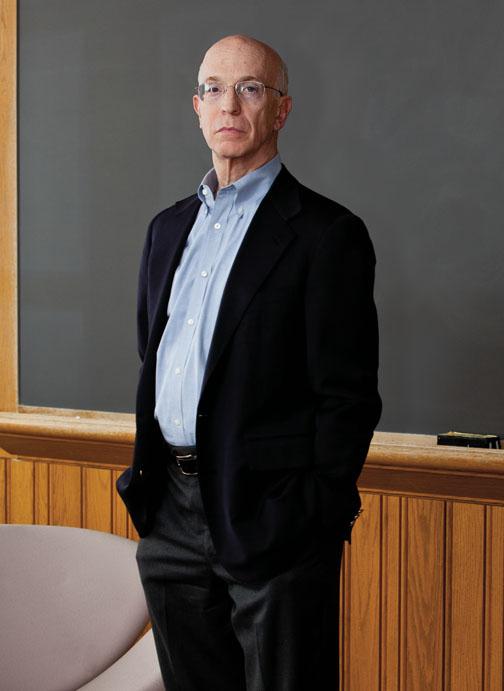

During the worst of the recession, in April 2009, Alan S. Blinder ’67 was invited to dinner at the White House.

President Obama wanted to speak with him and other prominent economists, including Blinder’s colleague Paul Krugman, though the guests didn’t know why. A week later, in the White House family dining room, the purpose of the meeting became clear. Obama sat with his top advisers, including then-chief of staff Rahm Emanuel, then-chairwoman of the Council of Economic Advisers Christina Romer, and Treasury secretary Timothy Geithner, and asked the economists on the other side of the table whether the federal government should seize the nation’s top banks.

At the time, there was great concern that the nation’s leading banks could collapse, possibly leading to a second Great Depression. Krugman, from his perch as a columnist at The New York Times, had been calling on Obama to nationalize the banks — he felt that widespread failure was possible, and with nationalization, the taxpayer could share in a banking recovery. Blinder, like many in the administration, felt that approach was too risky and could worsen the damage. As the economists went back and forth, “you could sort of deduce that Obama wanted to hear the reasons that some of these outsiders had been such vocal critics of the administration, although I had not been,” remembers Blinder. “He wanted to hear the interactions.” (Blinder believes the White House also hoped the dinner would prompt Krugman to become more sympathetic in his Times columns but adds: “History will record that it didn’t work.”)

Blinder’s position prevailed: The banks were not nationalized, and the industry stabilized.

To the public, Blinder, 65, isn’t as well-known as Krugman, his Nobel Prize-winning colleague. Like Krugman, the left-leaning Blinder is a public intellectual who often writes newspaper columns — though his frequently run in the conservative Wall Street Journal and tend to cite more statistics. Blinder has spent time in government service, figuring out how to marry the ideals of economic theory with the practice of diplomacy and political wrangling. Krugman chose instead the route of academic and commentator who embraces a more ideological approach and a sharper tongue.

But Blinder is a towering figure in economics circles, serving briefly as vice chairman of the Federal Reserve Board and influencing the last two Democratic administrations. Recently, he has emerged as a staunch defender of the Fed’s actions to bolster the economy and has met occasionally with Obama and Geithner to discuss ways to stimulate the economy and reduce unemployment.

The White House dinner discussion about the banks was not Blinder’s only contribution to the national debate: He prompted the administration to think seriously about what became one of its signature policies in response to the recession — the Cash for Clunkers program that created a subsidy for consumers to trade in old, gas-guzzling cars for new ones as a form of stimulus. Having encountered the idea in 1992 as a member of President Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers, Blinder began researching it again in 2008 as the economy began a steep decline. “We were grappling with — how do you stimulate the economy, how do you help the environment, how do you help the poor?” Blinder recalls. “With Cash for Clunkers, you had the trifecta.” He extolled the program’s virtues in a column for the Times, and eventually Geithner studied Blinder’s research and endorsed the idea.

Cash for Clunkers became “a turning point in the recession,” says Alan Krueger, another Princeton professor, who became chief economist at the Treasury Department. Overall, economists have been split about whether the program was worth its $3 billion cost, and how much it encouraged people to buy new cars who otherwise wouldn’t have in the near term.

Blinder — the author of one of the top introductory economics textbooks in the country — believes the recent financial crisis and recession have at least two main lessons for the nation.

First is the need for regulation and aggressive supervision by regulators: “The financial markets tend to run to excesses, and if there aren’t zookeepers, the animals dash out of their cages and may do bad things.” The second concerns the outsized role Wall Street has had in the economy in recent years. He is skeptical about the role “fancy finance” plays in American society. “A lot of the modern innovations were designed to create incredible complexity by which the top financial institutions could profit,” he says. “The irony, of course, is that a lot of them got caught when the music stopped.”

Today, Blinder says, the economy continues to improve. He expects 2011 to be “a good but not spectacular year,” perhaps with growth of about 4 percent. Unlike many economists, he has nary a concern about prices rising too fast. He does worry about the ballooning federal debt and deficit, which he warns will explode over the next two decades if action is not taken. But he doesn’t think any short-term steps to raise taxes or reduce government spending would be prudent. “The fiscal situation is paradoxical,” he says, noting that the country needs both government spending and tax cuts now to spur economic growth but needs to cut back spending and raise tax revenues in the long run to rein in the debt and deficit.

He has spent recent months attempting to assess the exact impact of the government’s response to the recession. Last summer, Blinder teamed with another well-known economist, Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics, to quantify what the government’s efforts meant to the economy. In a paper titled “How the Great Recession was Brought to an End,” they found that without the government measures, there would have been 8.5 million fewer jobs, and prices and wages would be falling as the nation experienced deflation.

Using a model developed by Moody’s, the two economists calculated that most of the benefit could be attributed to financial-market policies such as the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program, or TARP; the bank “stress tests”; and a strategy to stimulate the economy carried out by the Federal Reserve called “quantitative easing” — what non-economists call “turning on the printing press.” In particular, the economists wrote, TARP allowed financial institutions to continue operating, helped to shore up asset prices, and “ensured an orderly restructuring” of the auto industry. “When all is said and done,” the authors concluded, “the financial and fiscal policies will have cost taxpayers a substantial sum, but not nearly as much as most had feared and not nearly as much as if policymakers had not acted at all. If the comprehensive policy responses saved the economy from another depression, as we estimate, they were well worth the cost.”

When the paper was published in late July, “Democrats in Congress and the White House started praising us to the sky,” Blinder says of the response. “Republicans started attacking us as being lackeys and incompetent.” One critic, economist John B. Taylor of Stanford University, took Zandi and Blinder to task for acknowledging but then ignoring “poor policymaking” that preceded TARP. “How can one then argue that policy interventions worked, when viewed in their entirety they caused the problem?” he asked in his blog.

Blinder says he would give the Obama administration’s response a B or B-minus based purely on its merits. But “government work needs to be graded on a curve,” he says, because it’s so hard “to get anything sensible done.” And on that curve, he’d give the administration an A-minus.

“Sitting in my office in Princeton, I could have designed a vastly better stimulus,” Blinder continues. He would have included new tax credits for companies to hire workers and created a government agency to hire tens of thousands of people for public-works projects. He also would have favored a far more aggressive plan to help people at risk of losing their homes to foreclosure.

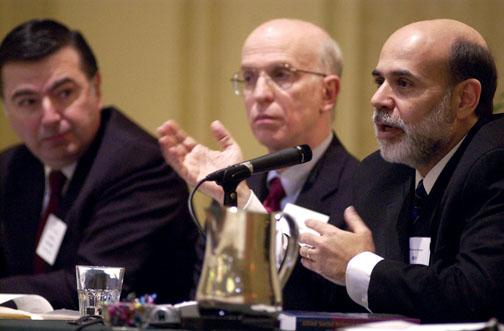

As for the monetary and financial policies overseen by the Fed — led by former Princeton professor Ben Bernanke — Blinder is even more generous, suggesting that Bernanke deserves an A-plus for his most recent actions. But he has not been impressed by all the Fed’s previous efforts, and most pointedly criticizes it for letting investment-giant Lehman Brothers fail, because it was clear that the failure would have wide repercussions through the financial system.

Bernanke has said many times that the Fed did not have the legal authority to save Lehman, but Blinder hasn’t bought the argument. “Ben, who’s a good friend, has said this to me several times, and knows I’m not convinced. When policymakers find something that simply has to be done, they tell their lawyers to kosher it,” he says. And after the collapse of Lehman, the Fed decided it would do virtually whatever was needed to prevent the financial system’s collapse. It announced a variety of programs, many of them stretching the legal limits of what the Fed was created to do. At times, Bernanke suggests in an interview with PAW, the traditional approach is not enough. “Ideological dogmatism or excessive attachment to orthodoxy is always a problem, but it’s particularly a problem in crisis situations where flexibility and aggressiveness are needed,” Bernanke says.

While many academic economists today take a highly theoretical approach to their field, Blinder long has had a personal, real-world interest. He grew up on Long Island, where his father sold garments and vending machines, was a restaurateur, and held a variety of other jobs. “Having grown up in a family that was prosperous one year and poor the next, I vowed to myself I was going to be a salaried employee,” he recalls.

He majored in economics because it was a field in which he could apply his mathematical bent while tackling social problems. While the Great Depression had fueled the field of economics in the 1940s and 1950s, the 1960s was a time of great economic prosperity. Economists were concerned with continuing that prosperity, and influenced by Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society, they hoped to extend that prosperity to the poor.

After Princeton, Blinder was a “young man in a hurry” to become an academic economist. He spent a year at the London School of Economics on a Fulbright scholarship, and another year teaching at a local college near Princeton while waiting to find out if he’d go to Vietnam (he didn’t, because of high blood pressure). He then enrolled at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which was regarded as having the best graduate economics program in the country. He returned to his alma mater as an assistant professor in 1971.

An extrovert, Blinder particularly has enjoyed teaching introductory economics. “It’s where I think my marginal social product — to use economic jargon — is highest,” he says. “You’re taking kids — and a lot of them are very smart kids who know zero about economics — and teaching them most of the important things. You’re giving students, some of whom are going to be corporate executives, congressmen, journalists, and so on, an eye-opening intellectual experience.”

In his Economics 101 lectures, Blinder always has referenced the real implications of economic ideas. “Alan showed how you could use rigorous analysis and evidence to understand the world better and then to adopt policies to make the world better,” says former student Douglas Elmendorf ’83, now the director of the Congressional Budget Office.

The real-world themes that sparked Blinder’s interest in economics can be seen throughout his work. His most cited paper, published in 1973, offers a methodology for determining why incomes differ when comparing two groups — say, men and women, or black men and white men. The formulas he introduced made it easier for economists to assess whether the reasons for unequal wages were due to sex, race, educational background, or other factors.

Blinder’s vision of merging economics and policy was best encapsulated in his 1987 book Hard Heads, Soft Hearts: Tough Minded Economics for a Just Society, which looked to solve social problems by using the principles of economics. He explains: “What motivated me to do it was just listening to a lot of political debates in which the Democrats were all soft-hearted — something I sympathized with — but they barely seemed to care about economic efficiency. The Republicans or conservatives were all about economic efficiency, the joys of markets, and didn’t seem to care about the plight of the poor. It started dawning on me that there’s a standard way of thinking about these things among liberal economists, but not liberals in general, that cares deeply about economic efficiency but also believes in transfer payments to the poor and unemployment.” Blinder wrote approvingly of lower tax rates with fewer deductions and loopholes, and argued against common liberal wisdom that said free trade cost jobs.

In 1992, Blinder served on President Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers, where he helped increase the earned income tax credit — a significant anti-poverty initiative — and tried to make the Clinton health-care plan more market-friendly (he failed). Two years later, Clinton nominated Blinder to serve as the No. 2 at the Fed. He found the experience frustrating because Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan, a Republican appointee, “just ran everything,” he says. “It sort of didn’t matter what Alan Blinder thought about anything.” After a year and a half, Blinder quit: “At the time, I felt I accomplished nothing or next to nothing.”

In 1996, Blinder returned to Princeton, eventually receiving a joint appointment to the Wilson School because he had grown estranged from the highly theoretical approach of the economics program. On his

return, Blinder, whose two sons also attended the University, started two consulting businesses on the side — one for banks, and one for wealthy investors and money managers who want to distribute savings over many bank accounts to avoid limits on federal deposit insurance. (The latter company was criticized by investor and author Nassim Taleb, who claimed it allows “the super-rich to scam taxpayers by getting free government-sponsored insurance,” but Blinder responds that the practice is legal, and federal officials have been encouraging people to open multiple accounts for decades.)

With the passage of the years, Blinder believes history has vindicated his time at the Fed. He pushed the body to take steps to reduce unemployment at the same time it tended to its better-known responsibility of keeping inflation at bay. In one controversial speech in 1994, Blinder insisted it could do both. “I was expressing the outrageous view that we could probably live very nicely in America with unemployment below 6 percent,” he says. “Before Greenspan finished at the Federal Reserve it had got down to 3.9.”

Blinder also “argued extensively and vehemently, with zero success” while Greenspan was chairman, for greater transparency and open communication, which he believed would increase market stability. Under Bernanke, the Fed has become more open, and the chairman says Blinder is one reason for that. “The trend in central bank communication in the last 20 years has been to greater and greater transparency and clarity about policy goals and intentions,” Bernanke says. “[Blinder’s] work, which supports both the theory and practice of communication, has supported that trend and been influential in helping the Fed and other central banks move toward more open policies.”

Over the past two years, Blinder has become the most prominent outside defender of the Fed — which has come under harsh criticism — and of Bernanke himself, often vouching for the Fed’s efforts to stretch its mandate to come up with a host of unconventional programs to keep the economy going. (Blinder acknowledges that the one job in Washington he’d consider is the Fed chairmanship, if Bernanke retired and he were offered the job.)

In November, Blinder’s support for his friend was evident as he opened his Wilson School graduate class. A few days earlier, Blinder had published a column in The Wall Street Journal defending Bernanke’s plan to print $600 billion of new money to give an extra lift to the economy. Now, the paper had published a response: a letter to the editor that accused Blinder of taking Americans “on a mythical excursion to a Keynesian utopia, a mythical land in which endless government spending is an amazingly effective job-creator.” It urged readers to take their “blinders off.” The letter was signed: Sarah Palin.

“What a weird world we’re living in,” said Blinder, seeming surprised that he found himself in a public spat with one of the most controversial figures in American politics. But the exchange was timely, as he had planned to lecture that day about the Federal Reserve’s response to the financial crisis. And it served another purpose, too — showing his public-policy students what life is like in the political realm.

Zachary Goldfarb ’05 is a financial writer at The Washington Post.