Sophia Echavarria was the kind of kid for whom Princeton seemed an impossible dream.

As a fifth-grader, she found herself struggling in a school that she describes as an unfortunate relic of the 1970s — a “school without walls” where one class could be struggling to complete a spelling bee within sight, earshot, and smell of a pizza party for the class next door. “It was very distracting,” Echavarria says.

At home, she recalls, “there were a lot of fights.” Eventually, her father left and her mother worked two, sometimes three jobs to support three children. Echavarria’s older sister dropped out of high school.

But Echavarria beat the odds. She graduated from Princeton in 2009 with a degree in English. Now living in California, she’s saving up for graduate school. Her goal: to obtain a master’s degree in fine arts and become a published science-fiction writer.

Echavarria credits her success to an innovative inner-city boarding school co-founded by another Princetonian, Rajiv Vinnakota ’93. Without Vinnakota’s SEED School, “I’d like to think I would have graduated high school,” says Echavarria, a member of SEED’s first class. “But I can’t say I would have ended up at a four-year college — at least not an Ivy League school like Princeton.”

The documentary Waiting for Superman, in which the SEED School plays a starring role, has added to a national debate about whether education reformers like Vinnakota are offering solutions for the nation’s public school systems, or just helping the relative handful of students lucky enough to get into their pedagogical boutiques. Charter schools — which receive public funding but generally are run independently — serve about 3 percent of the nation’s public-school children.

Princeton graduates are in the front ranks of the nation’s school-reform movement. Several are in top jobs at the U.S. Department of Education. Many others are pushing at a local level to close the achievement gap, founding schools, and leading nonprofit groups that are incubating examples of how good teachers and good principals can help even the most disadvantaged children succeed.

Education reformers believe they can change the system by creating what they call “proof points”: successful schools that explode the stereotypes about disadvantaged kids being unable to succeed academically and that can be models for the nation’s public schools. Very often they’re talking about charter schools, which are freed from the rules, policies, and union contracts that can restrict experimentation. (Not all charter schools, it’s important to note, are successful: A 2009 study of several thousand schools by Stanford University found them to be a mixed bag, with 17 percent reporting academic gains that were significantly better than traditional public schools, 37 percent reporting smaller gains than the traditional schools, and 46 percent performing at about the same level. Overall, charters serving low-income students appeared to be making the greatest difference — and that is where many Princetonians interviewed by PAW have focused their efforts.)

It’s easy to be cynical about the reformers’ chances for success, given that so many similarly well-intentioned efforts have foundered in the past. Vinnakota wasn’t even born in 1970 when Robert Burkhardt ’62 headed to San Francisco to launch what then was known as a “free” school — part of the then-in-vogue effort to break away from traditional curricula and classroom settings and promote more creative thinking. “I was going to change the educational system,” Burkhardt recalls ruefully. “You see how much it’s changed.”

Yet Burkhardt — who now runs a Colorado private school for disadvantaged students that aims to share effective practices with educators from around the country — and other reformers believe the system finally is changing.

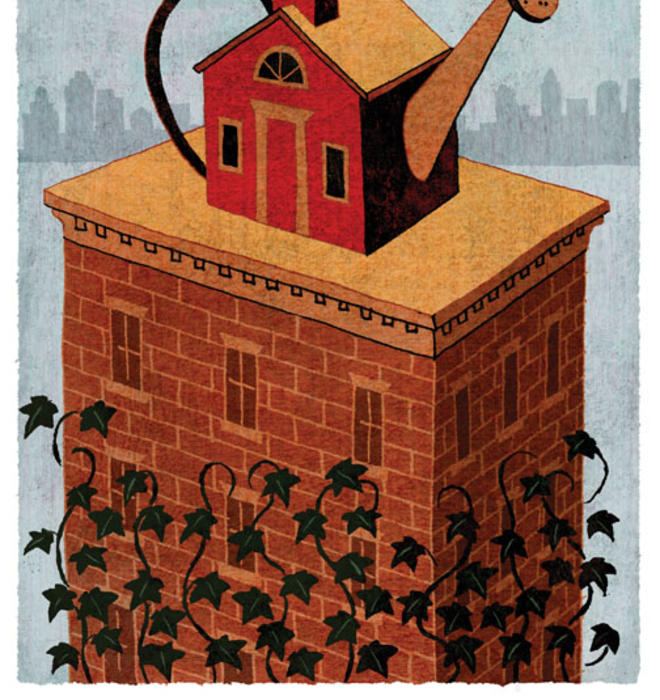

As its name implies, the SEED school is part of an effort to grow an education-reform movement from the ground up. It seems to be taking root: The first school opened in Washington, D.C., in 1998 and spawned a partner in Baltimore, with others in the works. Like the public school systems it seeks to change, the movement is decentralized and, at this point, disparate. But Princetonians who are involved in it believe it is gradually achieving what decades of presidential commissions and congressional legislation have striven for: fundamental change in schools that, according to all-too-many studies, are not working for the nation’s most disadvantaged children — and may not be providing adequate preparation even for middle-class students to compete in a global economy.

“I’m more optimistic,” says Dan Challener ’81, an education-reform veteran who heads the Public Education Foundation in Chattanooga, Tenn., which provides small grants and other support to local public schools. “I think the nation increasingly understands the importance of improving the public education system. It has gone from being an education imperative to an economic imperative. That’s important.” As a result, the nation’s governors “are starting to take education very seriously,” says Joanne Weiss ’79, the chief of staff to U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan. An effort by states to adopt “common-core” education standards — already endorsed by 43 states — will turn out to be “a watershed moment” in education reform, Weiss predicts.

Finding ways to help students of all socioeconomic backgrounds meet high standards is a preoccupation of many Princetonians who have been trying to reform education one school at a time.

At Eagle Rock, his highly acclaimed boarding school founded in 1994 and funded by the American Honda Company, Burkhardt has distilled the lessons he learned beginning in the 1970s into a program that combines demanding academics with an Outward Bound-like physical culture to turn around the lives of struggling students — all of whom promise to live without cars, alcohol, tobacco, and drugs, and to forgo sexual activity. “We’ve taken the kids who everyone has given up on — they’ve given up on themselves,” he says, “and impelled them to make changes in their lives.”

Burkhardt believes Eagle Rock has affected more than the lives of the students lucky enough to have gone there. Though the school can house fewer than 100 students a year, Burkhardt says he has entered “a larger conversation about the culture of expectation” by hosting as many as 1,500 education professionals a year, giving them an opportunity to study Eagle Rock’s methods and to consider how they might adapt those methods to a public school setting. “We’re effectively a private school in the public interest,” says Burkhardt.

Taking another approach, a 10-year-old organization started by Jon Schnur ’89, New Leaders for New Schools, has placed 700 principals in schools across the country. Graduates of the yearlong program run 25 percent of the schools in Washington, D.C., 20 percent of the schools in Baltimore and Memphis, and nearly 15 percent of the schools in Chicago, Schnur says.

Even more influential, say its fans, is the Teach for America program founded by Wendy Kopp ’89, which celebrated its 20th anniversary in February. Critics have charged that Kopp’s program is producing education-reform dilettantes who spend a year or two in a classroom before moving on to more lucrative fields.

Not so, insists Katherine Bradley ’86, whose CityBridge Foundation worked with TFA to make Head Start available for every child in the nation’s capital. More than two-thirds of TFA alumni remain involved in education, says Bradley, though not necessarily in the classroom. Weiss believes that the movement of TFA graduates into leadership positions in school reform is stoking the reform movement’s momentum.

One example: TFA-trained Jason Kamras ’95. Named national teacher of the year in 2005 by then-President George W. Bush for his successful efforts to teach middle-school math and social studies in Washington, D.C.’s underperforming school system, Kamras now directs “teacher human-capital strategy” in that school district and has been implementing a controversial new teachers’ contract that allows for merit compensation, reduces the role of tenure and seniority, and ties teacher evaluations to student achievement. The changes won Kamras’ former boss, ex-D.C. schools Chancellor Michelle Rhee, national recognition — but might have cost her and Mayor Adrian Fenty their jobs when voters turned off by Rhee’s take-no-prisoners style and confrontational approach to the local teachers’ union rebelled in the November election. Rhee resigned, but Kamras has remained at his post, convinced that Rhee’s reforms will outlast her.

In Los Angeles, another TFA alum, Brian Johnson ’99, founded the Larchmont Charter School, which tries to recruit a racially and socioeconomically diverse student body. “We have the children of network presidents and Oscar and Emmy nominees along with children of first-generation immigrants,” he says. Johnson believes his school, which has now expanded to two campuses, has an impact on the larger public school system by demonstrating what’s possible. “It begins to chip away at the excuses that exist to preserve the status quo,” he says.

Interviews with Princeton alumni involved in education reform suggest a consensus on what it will take to turn around the nation’s public schools: staffing them with strong principals and teachers; providing a variety of opportunities to match the diversity of student aptitudes; having high expectations for all students, including those whose ZIP codes do not appear to destine them for success; and using data — not just to evaluate how students are doing, but to figure out which teaching methods work and which don’t.

At Brown University, where he obtained his master’s degree in education, Eric Westendorf ’94 imbibed a “very anti-testing” view of how to measure student achievement. Now the chief academic officer of a growing charter school in Washington, D.C., he has changed his mind. “Before No Child Left Behind, there was no sense of urgency,” says Westendorf, referring to the landmark — and controversial — education-reform law enacted under President Bush to provide national benchmarks for student progress. “While standardized testing is a two-dimensional measure, it is a measure,” Westendorf argues. “If you can’t measure anything, you don’t know what’s working.”

Initiatives pioneered in charter and other innovative schools already are finding their way into large school systems, says Marc Sternberg ’95, deputy chancellor of the New York City schools. As a former White House fellow, Sternberg worked on the Race to the Top program championed by President Obama, which provided $4 billion to districts willing to make reforms such as establishing merit-based pay. That program helped foment change even in districts that didn’t win, he says. “I think it’s a significant milestone in the reform movement,” Sternberg says. “Things that were outside the mainstream suddenly are being embraced.”

Here are three stories of alumni in the forefront of change:

Rajiv Vinnakota ’93

FOUNDER, SEED SCHOOL AND FOUNDATION

The seed for Vinnakota’s innovative education concept — a college-prep boarding school located in an inner city — was planted in a conversation at a 1994 Princeton reunion. Vinnakota, then a management consultant in Washington, D.C., was making his first trip back to campus since graduation, and the conversation with classmates turned to the poor quality of urban education and how to give inner-city kids a chance at a place like Princeton.

“One of my friends said, ‘There are boarding schools for privileged kids, why not ... ?’” Vinnakota recalls. He couldn’t stop thinking about the question. In 1996, he took a leave from Mercer Management Consultants and spent two months traveling the country, to talk to educators about whether the concept would work. “I was very skeptical,” says one of his bosses at the company, Vasco Fernandes ’77. “But I thought that if anyone could make it work, he could.”

The following year, Vinnakota and Eric Adler, a Penn grad and fellow consulting veteran, left their jobs to begin making the idea a reality. They worked 18 months without salaries. Today, they preside over a foundation that has created a thriving charter school in one of Washington’s toughest neighborhoods and a foundation that gets daily inquiries from education leaders across the country interested in franchising the model. SEED has opened its second school in Baltimore, and conversations are under way about opening schools in Cincinnati, Miami, and New York City. The program, which began its life as Schools for Educational Evolution and Development but now goes by the acronym, got rave reviews on CBS’ 60 Minutes, and had a starring role in the documentary Waiting for Superman.

Fernandes is the chairman of the school’s board; Pyper Davis ’87 is the chief operating officer. Major financial backers include Jack LaPorte ’67, Katherine Bradley ’86, and Marc Miller ’69. Vinnakota also credits former Princeton Alumni Association president Brent Henry ’69 with helping him find education experts during the 18 months he spent refining the concept before he and Adler began fundraising. “It’s a whole Princeton juggernaut,” Vinnatoka jokes.

The idea behind SEED, says LaPorte, is to provide a “24-hour-a-day, five-day-a-week” supportive environment for disadvantaged students.

The original SEED school, which houses 325 students in grades 6 through 12, is built literally on the foundations of an abandoned public school that, Vinnakota says, repeatedly was torched by the crack addicts who occupied it before SEED took over. The Washington school, which opened its doors in 1998, receives about three applications for every available slot. Students are chosen by lottery.

The four buildings that now occupy the site include a gym, a cafeteria, and dormitories that include three adult apartments per floor. About 16 adults live in each building, providing round-the-clock supervision for the students from Sunday evenings, when they check in, until Friday afternoons, when they return home for the weekend. The school offers mental and physical health programs and other social services.

There’s no question that the boarding-school model is pricey. SEED’s per-pupil cost is $35,000 a year — almost three times what it costs to educate a child in Washington’s traditional public schools. And the school would not exist without extensive contributions. Vinnakota says he and Adler raised $20 million and financed another $14 million to launch the SEED school in Washington. For the Maryland school, they raised $35 million and financed $25 million.

But “the payback is tremendous,” Fernandes argues. In Washington, about 90 percent of SEED students come from families without a college graduate; in Maryland, students must meet two of 10 risk factors to qualify for admission to SEED. These include having a record of truancy or suspensions, coming from a household below the poverty line, or having a parent who is incarcerated. Fernandes insists that SEED more than recoups the social investment by turning at-risk youths into productive taxpayers.

“Obviously you wouldn’t want the whole population going to a boarding school. That would be tremendously expensive,” he says. But for “kids at the margin,” he says, it’s worth the investment in students who might otherwise end up on the unemployment line or in jail. “Look at the costs that might hit society otherwise.”

Some lessons from SEED could be adapted for traditional public schools — most involving expectations. SEED students are inculcated with the idea that they will go to college from the minute they walk through the school’s doors. The dorms are divided into “houses,” each named after a university that a SEED alum has attended. (The Washington school’s Princeton house is named in honor of Echavarria.) Students are required to research their house’s university and present papers about the schools. College pennants line the school’s hallways, and university tours are part of the curriculum.

The library and a faculty lounge above it offer more ideas for improving public education. One wall of library shelves holds books in bins labeled from A to Z, designating their level at reading difficulty. Students are required to read every day and are told what letter of the alphabet matches the grade level at which they should be reading. They are, one faculty member says, encouraged to “own” their path to progress.

Upstairs, a big bulletin board in the faculty lounge tracks students’ reading progress. The chart is color-coded to make clear which teachers are responsible for which students. So the achievements and the shortcomings of everyone — teachers and students — are in plain view of the entire faculty. When students begin to lag behind, a team effort is put in place to help them.

Vinnakota is pleased with the success of his experiment, but not satisfied. “I feel like we have proven the success of the model: 91 percent of our 9th graders graduate; 97 percent of them get accepted to a four-year college,” he says. “We are on our way, but we need to build more schools.”

Marc Sternberg ’95

DEPUTY CHANCELLOR, NEW YORK CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS

At Princeton, Marc Sternberg never imagined a career in education. He majored in politics and wrote his thesis on “an obscure bus boycott” in his hometown of Baton Rouge, La.

But Sternberg also was an active leader in the campus Jewish community, which “was very much about service.” He worked for the Student Volunteers Council tutoring kids in Trenton. He briefly considered law school after graduation, but decided to sign up for Teach for America instead. His starting salary in the Bronx high school where he was assigned: $28,000. “It ended up being the single best decision I have ever made,” says Sternberg, even though he recalls a “very rough” first semester.

Sternberg spent three years teaching social studies to middle-school students in the Bronx, and then headed to Harvard to obtain a master’s degree in education and an M.B.A. His application essay described his vision for opening a charter school in the Bronx: Sternberg believed the kind of reform he envisioned best could be achieved in a smaller environment.

After Harvard, he went to work for Victory Schools, a New York-based company that was helping to operate charter schools in the Northeast. In 2003, Sternberg got a chance to realize the vision he had outlined in his Harvard essay: Then-New York City Schools chancellor Joel Klein asked him to launch a new public school in the Bronx, not far from the middle school where he began his teaching career.

The Bronx Lab School, which opened in 2004, occupies one floor of the phased-out Evander Childs High School, a 3,000-student factory that had a 40 percent graduation rate. Today, the Lab School is one of several smaller schools that operate on what’s now known as the Evander Childs campus. Each has a special focus: The Lab School, for example, focuses on college preparation.

As the Lab School’s founder, Sternberg had wide latitude. “I hired my own teachers. I decided what the curriculum should be,” Sternberg says. “My vision was that the kids going to Bronx Lab would have the same college-prep experience that I had.” Today, Sternberg says, the graduation rate at the Bronx Lab is 85 percent — a result he says he achieved by recruiting good teachers who had high expectations.

Meanwhile, Sternberg is now effecting change on a wider scale as a deputy chancellor of the city’s schools, a job he took in 2009. As deputy chancellor for portfolio planning, he heads “the team that evaluates how schools are performing.” His team also decides which schools will be shuttered for poor performance. “We make the tough calls,” he says.

It’s part of a systemwide overhaul, implemented by Klein, that allows students to choose schools based on their aptitudes and interests and forces schools to compete based on their results: graduation rates, college admission, or job placement. Before Klein imposed high school choice, a student could attend only the neighborhood high school, which meant “an eighth-grader’s ZIP code essentially determined their likelihood of going to college,” says Sternberg.

So far, Sternberg’s team has closed 91 New York City schools and opened 474 in their place. Not all the schools Sternberg closes are old public high schools. The New York Times recently chronicled his ongoing efforts to close a stylish Manhattan charter because the students weren’t measuring up on test scores. The vast majority of the new ones — 365 — are not privately run charter schools, but traditional public schools. It’s proof, Sternberg says, that reform is possible within the public school system. Even in traditional public schools, he says, “we’re producing charterlike results.”

Ron Brady *92

FOUNDER, THE FOUNDATION ACADEMY

When Ron Brady earned his master’s degree from the Woodrow Wilson School, his ambition was to teach in a New Jersey public school. He was willing to obtain the necessary certification and, “being an African-American male, I thought I’d make a pretty important contribution,” he says.

Out of the scores of inquiries Brady made, he says he received exactly one offer. It came in June. The school-district official who made the offer told Brady he could have a job but added, “I can’t tell you where, or what you’re going to teach.” Because of rules relating to seniority and teacher transfers, Brady might not know those things until a week before school started. Brady protested that it would leave him no time to prepare.

“That’s an example of a system that doesn’t work well,” Brady says. “It should be no surprise to anyone that I said no to that.”

Instead of joining the system, Brady set out to change it. He joined Edison Schools, the for-profit school management company founded by entrepreneur Christopher Whittle, and later worked as a special assistant to the chancellor of the New York City schools helping to restructure failing schools. From there he moved to New Jersey where, after working in the state education department, he served as principal of the Trenton Community Charter School. Four years ago, he helped to found his own charter school in the same city.

The Foundation Academy’s name comes from its mission: Brady’s goal is to give every student the fundamentals he or she will need to succeed in college. His target audience is huge: Of every 100 students who enroll in Trenton schools, Brady says, only eight emerge prepared to start college — a figure he bases on the number of dropouts plus the students who fail to pass both parts of New Jersey’s high school proficiency exam.

Foundation Academy serves 200 students in grades five through eight, but Brady has big plans for expansion. His ultimate goal: 1,000 students in a school that will begin with kindergarten and run all the way through 12th grade. The school has added one grade per year since its 2007 opening; Brady hopes to offer slots for 340 students in the fall.

Brady pushes his students and staff hard. The Foundation Academy keeps longer hours than its traditional peers — the school day begins at 7:30 a.m. and ends at 4:30 p.m. — and operates on a longer year: 200 days of classes, compared to the standard 180. It’s a non-union shop, he points out, and “our staff does whatever it takes to meet the needs of students.”

Students are tested every six to eight weeks in language arts, math, science, and social studies, which also ends up being an evaluation for teachers. “We sit down with our teachers every six to eight weeks,” says Brady. Based on the students’ test results, the discussion revolves around “where the teaching needs to improve.”

There’s one unusual requirement: All Foundation Academy students must learn a stringed instrument and participate in the school’s string orchestra. Brady, who took up cello as an adult, believes that it inculcates one of his core principles.

“When you have your entire school performing in a string orchestra, all it takes is one person to play the violin a half-measure too long or one person to mess up a note, and you notice it,” he says. The exercise of learning to play a “challenging instrument” as part of an ensemble “epitomizes the notion that all of our students together are achieving success.”

Brady does all of this on a budget that provides him about 70 percent of the per-pupil stipend that Trenton’s mainstream public schools get. Nonetheless, Brady says he pays his teachers — whom he recruits nationally — about 10 percent more than what they’d make in a traditional New Jersey public school. He makes up the difference by pinching administrative costs, and takes a salary that’s “considerably less” than what he would earn in the public school system.

The school’s proximity to Brady’s alma mater has helped. Todd Kent, the director of teacher certification in Princeton’s Program in Teacher Preparation, is a board member. Foundation Academy students attend the Princeton Blairstown Center, where they engage in outdoor learning activities designed to build character and encourage teamwork. And the University’s Student Volunteers Council provides up to 20 tutors each week.

How’s it going so far? “We are outperforming the Trenton school district at all grade levels,” Brady says. But he won’t consider his experiment a success until his students can match the achievement levels of surrounding suburban communities. “We’re not there yet,” Brady says, “but that’s the goal.”

Kathy Kiely ’77 is managing editor of politics at National Journal.

6 Responses

Eileen H. Bakke ’75

10 Years AgoCreating great schools

Kathy Kiely ’77’s “Schoolhouses rock” (cover story, March 2) highlights the impressive achievements of numerous Princeton alumni dedicated to changing education. Many of us aren’t Waiting for Superman. In 2004, my husband and I founded Imagine Schools, a national operator of public charter schools, to bring educational choice to families who otherwise would be trapped in failing zoned schools. In our seventh year, nearly 40,000 students in 73 charter schools are part of the Imagine “school system.”

One reform deserving of additional focus is the performance tool used to evaluate students, teachers, and schools. To make merit pay work and to individualize education, Congress should adopt a learning-gains approach to replace No Child Left Behind’s Adequate Yearly Progress designation. NCLB tests provide an incomplete performance picture, especially for students who are below grade level. At Imagine Schools, we test all students at the beginning of the year to provide baseline academic information and again in the spring to assess how much each student has progressed. Same-student learning-gains data enable us to measure each teacher’s effectiveness and to celebrate each student’s academic growth, not simply their proficiency at a point in time.

As I expressed as a participant on last year’s Reunions education panel, charter schools’ most potent contribution to reform is offering choice and competition. Parents know quality and will vote with their feet. Parents understand that there are elements in addition to strong academics that create great schools: character development, leadership, a loving environment, and effective teachers who serve as positive role models. Our reform efforts will be successful when students graduate being both good and smart.

Mark Peevy ’92

10 Years AgoSchool-reformers' impact

A great article. I’m doing similar work in Georgia as the executive director of the Georgia Charter Schools Commission (our state’s authorizer of charter schools), and it is very encouraging to see the impact that Princeton alums are having in the education-reform field.

Reed Dyer ’94

10 Years AgoWanted: More alumni in education

As another alumnus who has spent his career engaged in bringing underserved children a high-quality education, I was heartened to see the PAW give voice to Princeton’s role in education reform. Or was I?

While I appreciate the hard work being done at the student, school, and district level, I can’t help but wonder what Princeton alumni could accomplish if more than a smattering of our ranks decided to take up the proper treatment of our children as a cause worthy of their attention.

Education has always had pockets of excellence. While these examples are inspiring, they represent no significant movement toward truly providing children — especially those whose families have always been underserved — with a more effective, more humane, more empowering system. I go back to your earlier report (Campus Notebook, Nov. 17) that of the members of the Class of 2010 who had jobs by graduation, 60 percent took positions in financial services or consulting. If that many Princetonians decided to do something truly valuable with their lives and throw their energy and talent toward education, then not only would you have something noteworthy to report, but we actually might start treating our youngest, most vulnerable citizens with the dignity they deserve.

Charles M. Smith ’59

10 Years AgoLooking beyond academics

A recent article in PAW describes how Princeton graduates are working to improve education through creating an optimal learning environment.

In addition to the learning environment, the overall circumstances of a child’s life impact the ability to learn. Extreme poverty, low expectations, homelessness, poor health, absent positive role models, and poor nutrition are but a few of the factors that can profoundly influence the success of educational efforts.

In Santa Fe, N.M., a community-based organization led by Bill Carson ’50 was formed to provide general support to students in two elementary schools. Volunteers serve as role models, mentors, and tutors. Books, atlases, and dictionaries are given to all children. An affiliation with a community health center has facilitated access to medical, dental, and preventive care. A program coordinator develops a variety of activities. Parents are encouraged to participate. An extraordinary outdoor athletic facility has been installed at one of the schools. Extensive vegetable gardens are tended by the students. The organization has raised money to support school nurses, physical education teachers, administrative support, and a librarian. A family center has been established to deal with the social and emotional problems of the children and their families.

The benefits of these efforts are apparent. Staff morale and the learning environment have improved. Parental involvement has increased. The health of the children has improved. Academic performance has improved. And graduates of these two schools seem to be doing better in middle school than graduates of other elementary schools.

This experience in Santa Fe demonstrates the importance of providing general as well as academic support as part of a comprehensive program to enable students to derive maximal benefit from their educational experience.

Willis Freemantle ’82

10 Years AgoImproving the schools

Kathy Kiely ’77’s enthusiastic article about education reform (cover story, March 2) prompts me to write from a tempered perspective. One of the most troubling aspects of the current trend, seen in the programs she highlights, is that few reformers have actual teaching experience. At most, they trained (to varying degrees) for the classroom, and taught only for a short time. In other professions, this would create a credibility gap. But it seems that any type of academic background is considered adequate qualification for being an expert in education reform.

I have taught for 16 years in the public schools. Like millions of my colleagues, I work every day to improve lives. Now my profession has become a lightning rod for national reformers trying to correct the injustices of society. The teachers I know feel that such a mission is unrealistic and unfair. We strive to maintain excellence under increasingly challenging conditions: shifting demographics, “readiness to learn” issues, large class sizes, special populations, etc. Believing in the worth of all of our students, we struggle to give of our increasingly rationed selves. It now appears that we, as a profession, are being held responsible for the very problems we have been facing down every day.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m grateful for the young, fresh innovators featured in PAW. I think some reforms are needed, and it’s always important to try to make a difference. I just wanted to speak up for all of us teachers who find ourselves in a difficult spot. Most of us are doing all we can. We need support, not blame.

Jasmine Alinder ’91

10 Years AgoCharter schools help only a few

As a parent of a child in public school, I found this article to be appallingly uncritical of the charter-school movement. In Wisconsin, where I live, independent charter schools strip $57 million from public school aid. These charter schools exacerbate the squeeze on public schools by siphoning money away from them, and for what? Because they outperform comparable public schools? No.

Even if boutique charter schools were the magic bullet, they are neither sustainable nor viable for the vast majority of kids. Rajiv Vinnakota ’93 deems the $35,000 he spends per pupil for his full-service SEED charter as worth it for “kids on the margin.” I couldn’t agree more. But in my daughter’s school district here in Milwaukee, we have about 85,000 K-12 students, and 82 percent (or 69,700) of those children qualify for free or reduced lunch and therefore would qualify as “kids on the margin.” Multiply that number by SEED’s per-pupil expenditure, and you have an annual cost of over $2.4 billion. That’s about twice the budget of the entire Milwaukee public school system. Our newly elected governor has proposed severe budget cuts, however, and new policies that will further break the public school system by expanding independent charter schools and the voucher program.

I celebrate SEED’s successes with individual students no less than anyone else. But if we want to save public education, we need to find a way to do so for all of our country’s children, and stop blaming underfunded public schools for not living up to superhero standards. A high-quality public education is a right for all of our children, not the privilege of a few.