A fall semester course in the Near Eastern studies (NES) department sparked controversy — and letters of concern, including from the rabbi at the University’s Center for Jewish Life (CJL) — for a reading list that includes a book that claims Israelis intentionally and systematically maim Palestinians and harvest their organs.

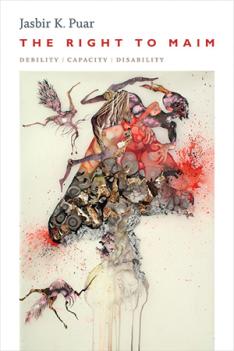

The 2017 book, The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, and Disability, was written by Jasbir Puar, a professor of women’s and gender studies at Rutgers University. The publisher’s website describes the book as culminating “in an interrogation of Israel’s policies toward Palestine, in which [Puar] outlines how Israel brings Palestinians into biopolitical being by designating them available for injury. Supplementing its right to kill with what Puar calls the right to maim, the Israeli state relies on liberal frameworks of disability to obscure and enable the mass debilitation of Palestinian bodies.”Satyel Larson, an NES assistant professor, included Puar’s book in her course, The Healing Humanities: Decolonizing Trauma Studies from the Global South, which currently has 13 enrolled students. Larson and Puar did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

In a letter to the CJL community sent earlier this week, Rabbi Gil Steinlauf ’91 said that Puar’s “unsubstantiated and harmful accusation that Israel aims to physically disable Palestinians as a means of control” has led to fear “about the negative impact of Jasbir Puar’s damaging and unproven views on the discourse on our campus, as well as the safety and well-being of our Jewish and Israeli students.” Steinlauf also said Puar “has previously and falsely accused the Israeli military of intentionally harming Palestinian children, harvesting Palestinians' organs, and other crimes reminiscent of classic antisemitic tropes stemming from the blood libel of the Middle Ages.”

Steinlauf said he wrote to Larson and NES department chair Behrooz Ghamari-Tabrizi “asking them to reconsider the impact of this text and to explore alternative ways to teach the course without including an author whose rhetoric and writings have deeply hurt many in the Jewish community.”

In an interview with PAW, Steinlauf said “my role is not to make demands. My role is to ensure that we have an atmosphere and a culture on campus that is constructive, that is sensitive to the experiences of everyone, and is safe for all groups.”

“Thank God we live in a free country where ideas can be expressed freely, but with freedom comes obligation and responsibilities to ethics,” said Steinlauf. He is of the mind that “we all have an ethical obligation when we present information to do it responsibly, and to do it in a way that takes into consideration the potential hurt, pain, and even harm that ideas and the way that ideas are presented can impact others.”

Princeton’s Alliance of Jewish Progressives (AJP) took a different stance, stating in an open letter in response to Steinlauf that “this latest attempt to silence educational discourse related to Israel-Palestine is part of a pattern in which the CJL aims to interfere with academic and co-curricular events, inquiry, and debate on campus.”

AJP stated further that “rather than contending with the horrific fact that Israel, like other countries, engages in human rights violations — having illegally harvested the organs of both Palestinians and Israelis, which is well-documented — the CJL perpetuates a rhetoric of Jewish and Israeli exceptionalism, which is deeply problematic.”

PEN America, a nonprofit that champions free speech, published a press release in support of the professor’s decision. Jonathan Friedman, director for free expression and education at PEN America, said the inclusion of the book on the syllabus is not “an invitation for antisemitic violence.”

“University education is meant to challenge minds and be a place for open exchange about global political issues, even when they are contested. It would be highly misguided — not to mention an overt violation of academic freedom — if Princeton acted on calls to remove the book in question or fire [Larson] for teaching it,” said Friedman.

Ronald Lauder, the president of the World Jewish Congress, called for Larson to be fired in comments made to The New York Post.

The University declined to comment on Larson’s course or the objections to the inclusion of Puar’s book in its syllabus. At the September faculty meeting, President Christopher Eisgruber ’83 reaffirmed the University’s commitment to academic freedom, which he said “protects your right to decide what to teach and how to teach it. That right, like the right to free speech on campus, is very broad indeed, and we will protect it.” He added his hope that criticism of syllabi is made “in constructive spirit appropriate to this scholarly community.”

Princeton’s Rights, Rules, Responsibilities states that “the University is committed to free and open inquiry in all matters” which “guarantees all members of the University community the broadest possible latitude to speak, write, listen, challenge, and learn.” However, Princeton also reserves the right to “restrict expression that … constitutes a genuine threat or harassment.”

Steinlauf declined to say if he thinks that sort of restriction applies in this case. He told PAW that Puar’s book “is viewed as deeply problematic and potentially harmful by many strong and reputable voices in the Jewish community,” though he said those views are “unsubstantiated in some areas.”

In a 2020 op-ed in The Daily Princetonian, Eisgruber wrote that “freedom of speech allows not only for genteel conversation but also for harsh language, impassioned argument, and provocative rhetoric. Of course, it also permits all of us to criticize statements that we find offensive or irresponsible, even if that speech is fully protected from punishment or discipline.”

The College Fix first reported on Puar’s book being included in the class, and soon headlines appeared from news media outlets such as the New York Post, Fox News, and The Jewish Journal.

Amichai Chikli, the minister of diaspora affairs in the Israeli government, wrote a letter dated Aug. 9 to Eisgruber and Dean of the Faculty Gene Jarrett ’97 condemning the book, which he called antisemitic propaganda, and others, such as Arsen Ostrovsky, CEO of the Israel-based nonprofit International Legal Forum, have also written to Princeton administrators expressing concern.

Earlier this year, Palestinian writer and activist Mohammed El-Kurd was invited to give a talk on campus that also caused controversy and prompted Steinlauf to speak out at the time against “the incendiary and hateful language about Jewish people that Mr. El-Kurd uses,” according to The Daily Princetonian.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to include the Aug. 22 comments by PEN America and the Sept. 11 faculty meeting comments by President Eisgruber and to expand upon the comments in Rabbi Steinlauf’s letter.