Bill Rosenblatt ’83 and Howie Singer Explore Technological Advancements in Music

The book: Focused on the last century of the music business, Key Changes (Oxford University Press) highlights the 10 technological advances that came along to shake up the industry. AI, radio, streaming, and CDs are among the advancements authors Howie Singer and Bill Rosenblatt cover in the book. They look not only at the impact of each disruption, but also the patterns that ultimately emerged in the industries’ response to each one. Key Changes includes interviews with Grammy-winning artists, producers, and executives who bring a variety of insightful perspectives to the topic.

The authors:

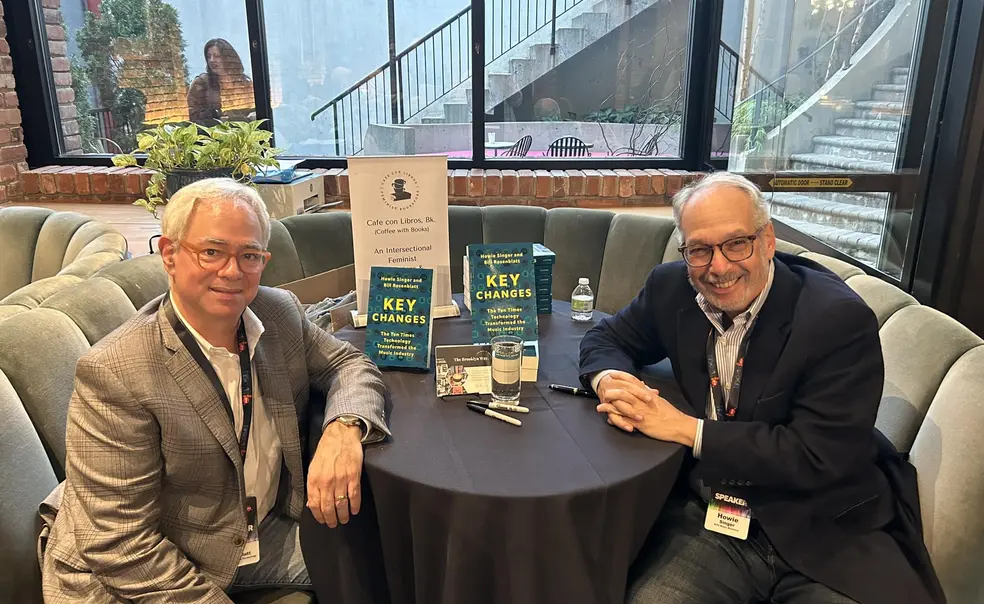

Bill Rosenblatt ’83 is president of GiantSteps Media Technology Strategies, a consulting firm that focuses on technologies related to media and copyright in the digital age. He teaches in the Music Business program at NYU, and he serves as an expert witness in intellectual property litigations. Rosenblatt is also the author of Digital Rights Management: Business and Technology and two other books, and he has written for Forbes and Publishers Weekly. He earned degrees in computer science from Princeton and the University of Massachusetts, and he is a charter trustee of Princeton Broadcasting Service, Inc., the nonprofit corporation that operates WPRB, Princeton’s student-run radio station.

Howie Singer is an expert on music industry technologies and was instrumental in the transition to digital music delivery. He served as senior vice president and chief strategic technologist at Warner Music Group. He currently teaches data analysis in the music industry at NYU Steinhardt. Singer earned his Ph.D. and master’s from Cornell, and his bachelor’s from Stony Brook University.

Excerpt:

From Chapter 4 - Vinyl

Consumers’ use of recorded music changed dramatically with the transition from 78s to vinyl records. The biggest catalyst was audio quality. The breakthrough sound quality of LPs made it conceivable, for the first time ever, that recorded music could sound as good as live. It shifted the perception of pre-recorded music from “Wow, we can hear a music performance!” to “Wow, we can hear a music performance that could sound like the real thing!” It also shifted preferences in the tone quality of phonographs from heavily colored (“soft, mellow, and flabby”) sound to sonic realism.

This shift coalesced with the post-World War II era’s economic prosperity and flight from apartments in cities to houses in the suburbs, as well as with adults’ increasing alienation from radio as it began to court the teenage Top 40 audience. The result was the high fidelity or “hi-fi” craze. Hi-fi equipment makers began to produce components—turntables, preamps, amps, and speakers—that consumers could select and combine into complete hi-fi systems. Entrepreneurs such as Saul Marantz, Sidney Harman, Bernard Kardon, and Avery Fisher started eponymous companies that made only hi-fi components, in contrast to electronics companies like Philco, GE, and RCA that made cheaper record players for the masses or big console systems for the living room. Hi-fi systems originally appealed mainly to classical music aficionados but eventually spread to fans of all music genres.

The market for hi-fi components exploded through the 1950s. One way to gauge how quickly this happened is to look at the catalogs of Lafayette Radio Electronics, a major retail and mail-order chain that ceased operations in 1981. Lafayette’s 1951 catalog listed 12 pages of component tuners, amplifiers, tuner/amp combos, turntables, tonearms, and speakers. But in 1959, when stereo had become available, stereo components took up 76 pages and were featured at the front of the catalog.

With hi-fi components, there was more emphasis on sound quality than on furniture style, more knobs and dials, lighter tonearms, and heavier platters, as well as escalating price tags. Aficionados attended hi-fi trade shows and constructed listening rooms in their houses with optimal placement of speakers and chairs, and acoustic wall treatments. “Demonstration records” were released featuring sound recordings and effects that showed off hi-fi systems’ capabilities. High Fidelity magazine debuted in 1951, followed by Audio (formerly Audio Engineering) in 1954 and HiFi and Music Review in 1958 (later Stereo Review).

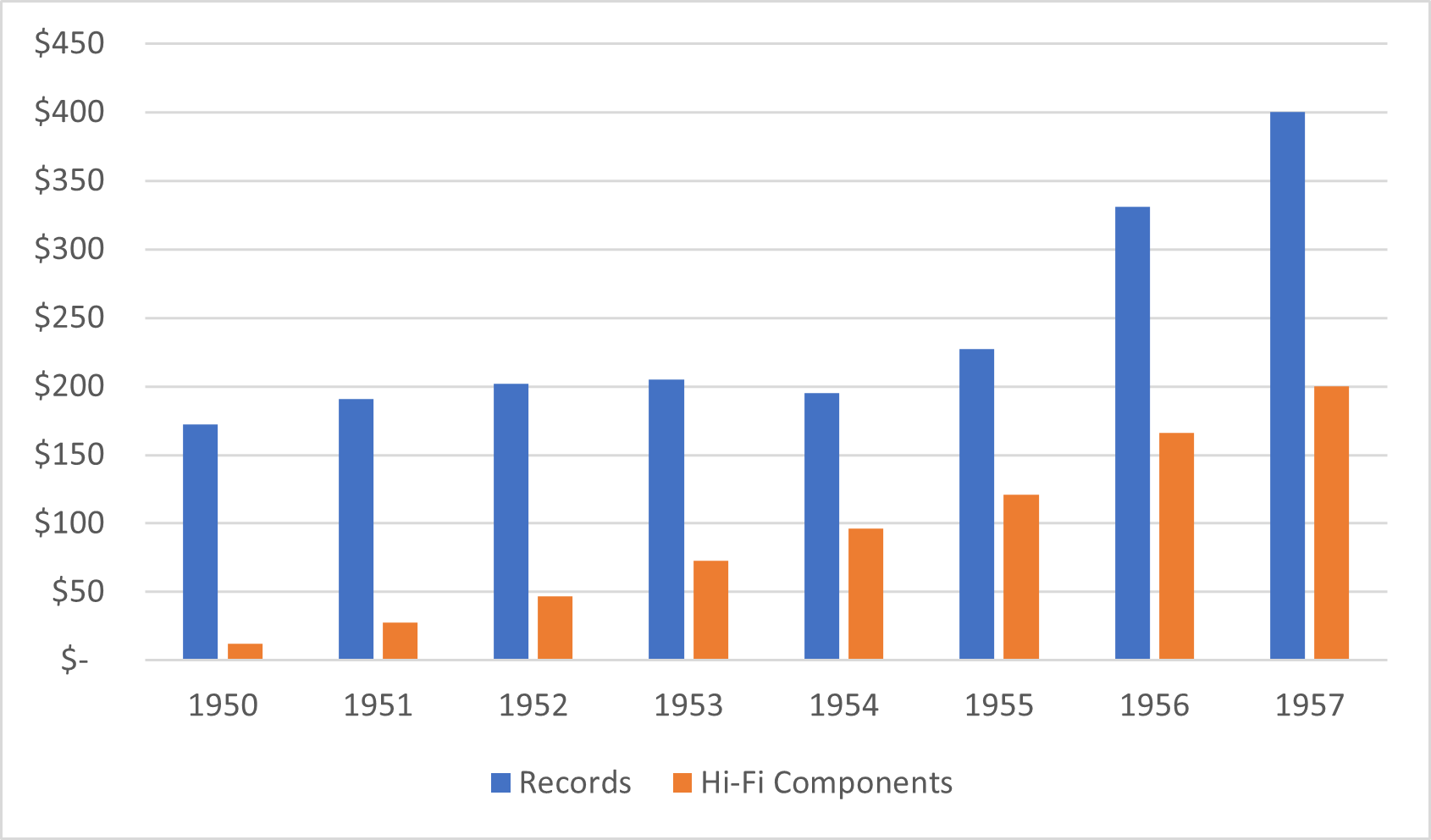

As Figure 4.6 shows, once the record industry recovered from the LP/45 format war in the mid-1950s, the hi-fi-component industry was about half as large as recorded music by revenue and grew at about the same rate. It continued to grow at more than 20% per year into the 1960s. The audio component industry continued in this vein until 1980, when it peaked at $1.8 billion, and then started to decline.

Although hi-fi turntables played 45s, consumers reacted very differently to 45s than they did to LPs. 45s were all about teenagers in the 1950s and 60s; the catalysts for change were low prices and small, portable form factors.

45s were another contribution to teenagers’ ability to listen to their music independently of their parents, the biggest being transistor radios. 45s were cheap: prices started at 65 cents, equivalent to about $6.50 today, compared to LPs, which hovered around the $4 mark ($40 today) in the 1950s. And they were portable, in the sense that you could take a few 45s over to your friend’s house to play them on their record player.

Transistors caused prices of consumer electronics to drop and sizes to shrink, so that teenagers could get their own record players; but the idea of a truly portable record playing experience remained elusive. It was impossible to play records in the car—though not for lack of trying: Columbia and RCA both tried to introduce shock-mounted under-dash automobile record players in the late 1950s, but they could not overcome the inherent mechanical problems of playing a record on a device attached to a vehicle moving down a road. By the 1960s, battery-operated portable record players began to appear, but they had limited uses: you could carry them around, but you had to stay in one place in order to listen to them, and you had to replace the batteries often. Transistorized record players that ran on AC power and were the size of briefcases were introduced in the late 1960s and were more popular; but they were more likely to sit on a teenager’s bedroom shelf than to be lugged over to friends’ houses. The tape cartridge formats that were emerging around that time would eventually supply portable music on demand.

Today’s vinyl renaissance is definitely a consumer-driven phenomenon; it is not a product of technological breakthroughs, changes in economics, or quirks in copyright law. It began as a hipster trend, as one of many quests for post-ironic “authenticity” and “artisanality” that manifested themselves in revivals of fedora hats, craft-brewed beer, fixed-gear bikes, and farm-to-table donuts. But vinyl would not be a billion-dollar industry today if it were still confined to hipsters.

Reasons cited for vinyl’s renewed popularity include its purported better sound quality than digital music. But that’s largely a myth, at least today. It’s true that the first generations of CDs and commercial digital downloads were made with immature encoding technology and/or at low bitrates, so they didn’t sound that great. But nowadays, encoding techniques have improved, bitrates have risen, and audiophile-grade digital-analog converters have been introduced. In other words, digital files can sound superb today. And most young fans’ playback equipment or earbuds aren’t good enough to tell the difference anyway.

The factor that most likely explains the renewed interest in vinyl is that it restores a sense of ownership to music fans. In the 2016 book The End of Ownership, two legal scholars, Aaron Perzanowski of Case Western Reserve and Jason Schultz of NYU, explain that digital files bought online aren’t really “owned” in the legal sense, and they advocate for reforms to establish ownership of digital content in law. They present consumer research that suggests that people expect ownership rights, even though they might not actually get them.

The problem is that consumers don’t feel a sense of ownership in digital files that merely take up space on their hard drives or stream to their portable devices. Despite record labels’ efforts to create digital “packages” out of digital music downloads, piles of bits are impossible to touch, admire, manipulate, sell, trade, and lovingly organize on your shelves. People didn’t feel that they had built a collection of anything after spending 99 cents on iTunes hundreds or thousands of times, and they certainly don’t feel ownership of music they listen to on streaming services.

LPs, on the other hand, are often true physical art objects and collectibles. They also bring an almost ritualistic sense of occasion in playing them, including a modicum of skill necessary to place the tonearm on the platter without damaging it. They make for a more engaged listening experience than tapping a button on a phone to start an MP3 or Spotify playlist, or even than shoving a cassette into a deck or a CD into a slot. LP cover art is much more attractive than the packaging for cassettes and CDs.

In fact, vinyl is far more popular than CDs in the used market, even though LPs’ sound quality deteriorates with use a lot faster than CDs. The online marketplace Discogs.com, for example, lists over 46 million vinyl items in its marketplace at this time of writing, compared to 18 million CDs, and the average price of a used LP is considerably higher than the average price of a used CD.

Finally, it’s worth noting that while the vinyl renaissance was originally mostly confined to classic rock and a bit of jazz, recent monthly sales charts from Discogs have seen more current pop, R&B, and hip-hop titles. This also suggests that vinyl’s renewed appeal is broadening beyond hipsters. Today’s vinyl fans have already picked up their copies of Dark Side of the Moon, Rumours, and Thriller (which were the best-selling albums on Discogs in December 2017); now they’re ready for something new, and record labels are meeting that demand with new releases. And the interest in vinyl has reached the mainstream: Taylor Swift sold 575,000 copies of the four different vinyl versions of Midnights in the first week of its October 2022 release, a unit sales number for a single album that the industry had likely not seen since the 1980s.

From Key Changes by Howie Singer and Bill Rosenblatt. Copyright © 2023 by Howie Singer and Bill Rosenblatt and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

Reviews

“Key Changes is particularly valuable in tracking recent economic developments, where the authors undoubtedly do have expertise.” — Andy Hamilton, The Wire

“A great read. What a pleasure to have the history of recorded music laid out so clearly and succinctly.” — Albhy Galuten, technology executive, Grammy Award-winning record producer, composer, musician, orchestrator, and conductor.

No responses yet