‘YOU MAKE ME FEEL LIKE AN ORACLE, the way you ask these questions,” Fred Buechner ’47 says, with some irritation, from his patio chair on Wind Gap Farm, the Vermont home where this writer and preacher has lived for more than 40 years.

Having just turned 86, and with 30-plus books to his credit, Buechner has earned the right to decide what he wants to talk about: perhaps about his career as a writing wunderkind who left the trappings of New York literary life behind to become a Presbyterian minister. Or about leaving a job in the ministry to return to writing, and winning the devotion of writers such as John Irving, Garrison Keillor, and Kathleen Norris. Or maybe about having a literary festival devoted to your work and your words printed on coffee mugs.

Buechner (whose full name is Carl Frederick Buechner, pronounced “Beekner”) is happy to talk about any of these subjects. He is not, however, interested in playing the role of sage. He does not want to talk about God or the afterlife or how to achieve literary success. Instead, sitting outside on a July day with the Green Mountains in the distance, he repeats the mantra that has come to define his life and work: “Pay attention to your life.”

“Because otherwise it’s just a lot of wasted effort,” explains Buechner, a cane by his side. “To live is to experience all sorts of things. It would be a shame to experience them — these rich experiences of sadness and happiness and success and failure — and then have it just all vanish, like a dream when you wake up. I find it interesting, to put it mildly, to keep track of it and think about it.”

Buechner may resist the role of oracle, but that has not stopped people from seeking him out. His books have earned him a large audience among both believers and skeptics. His writings are widely quoted and anthologized. Recently first lady Michelle Obama ’85 cited Buechner’s description of vocation: “where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet.” He has a large following in Christian colleges, and has delivered sermons at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., and at Westminster Abbey in London.

“He is just so eloquent and thoughtful,” says Bob Abernethy ’49, the host of Religion & Ethics Newsweekly, a PBS program that aired a profile of Buechner in 2006.“He sits up there, on that hill in Vermont, and he comes up out of himself, out of his own feelings and thoughts — that’s his greatest resource.”

“Probably right now, if you went around the country from Sunday to Sunday and listened to ministers, Buechner would surely be among the two or three most quoted,” says Dale Brown, director of the Buechner Institute at King College in Tennessee, a program that seeks to foster conversation on faith and culture. But beyond the pulpit, one of the most common refrains Brown hears about Buechner is: “I’m surprised I never heard of him before.”

If Buechner is not as well known as, say, his late contemporary Gore Vidal, perhaps it is because he is, in his words, “too religious for secular readers” and “too secular for religious ones.” That may be changing. Last year King College held a “BuechnerFest” exploring the various ways artists of faith engage the culture. A second festival is planned for 2013. The school sponsors an annual lecture, also named for Buechner, which has been given by the writers Ron Hansen, Barbara Brown Taylor, and Marilynne Robinson, among others. For Brown, the founder of the festival, the annual gathering was a natural way to honor Buechner. He believes Buechner’s work will continue to grow in popularity as more people discover it.

BORN IN NEW YORK CITY, Buechner attended the Lawrenceville School in New Jersey before matriculating at Princeton. His father also had attended Princeton and knew Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald — a literary connection, one family member suggests, that Buechner quietly treasures. Entering his library, a visitor and fellow alumnus is greeted with the question, “Have you read This Side of Paradise?”

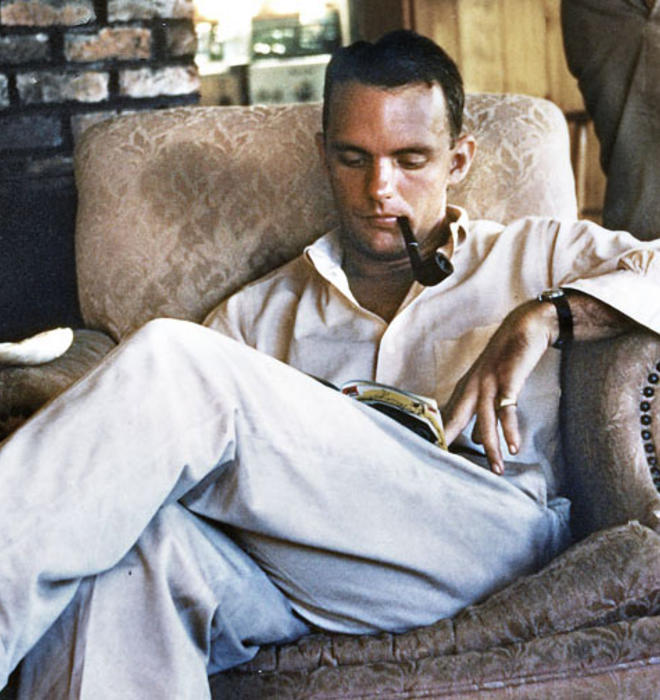

“I really knew two Princetons,” says Buechner, resting in an armchair and surrounded by thousands of books. “The first one was during the war, when everybody was being drafted or enlisting. It was just one drunken farewell party after another. Nobody did any work. I didn’t learn anything at all. I was in the Army for two years. When I came back, I was so delighted to be free again that I buckled down and learned a few things.”

In his second stint at Princeton, Buechner began work on A Long Day’s Dying, a novel that served as his senior thesis. His advisers were reluctant to allow him to write a novel, but he convinced them, and the book was published after graduation to wide acclaim. The novel, which Buechner describes today as “tortured, labyrinthine, elusive,” was compared to the work of Henry James. It was a New York Times best-seller and remains Buechner’s most commercially successful work. His second book, The Seasons’ Difference, was a critical disappointment, but he enjoyed a measure of reprieve when his short story “The Tiger” was published in The New Yorker in 1953 and won an O. Henry Award. It is about a Princeton undergraduate who dresses up as the mascot at a football game; later, at a party, a girl asks him to tell her about tigers. He never gets the chance. “If I had, it would probably have gone something like this,” the narrator says. “Tigers are wild-hearted creatures of great strength and dignity who are to be found in jungles or in zoos and nowhere else. There was a time when every once in a while you’d see one parading around, unhurried and in superb control, at a football game, but that was 25 years ago, so if you think you see one there nowadays, you can be sure it’s only a fake.”

Buechner did not remain among the New York literati for long. After he began studying for the ministry at Union Theological Seminary in New York, moved by the example of the pastor of the Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church, one reviewer commented that “Mr. Buechner has put his foot in it.” Even at a time when Union was home to luminaries like Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich, Buechner’s choice was greeted with puzzlement.

“It was the kiss of death, in a way,” Buechner says of his decision to be ordained. “When book reviewers saw that I was a minister, what they read was not the book I had written, but the book they thought a minister would write.”

According to Brown, Buechner’s journey fits a pattern. “It is the [C.S.] Lewis model,” Brown writes in The Book of Buechner: A Journey Through His Writings. “Erudite academic sheds the robes of the dons for the cloak of Christ.” However, he notes, “the story is more complicated and more interesting than the formula suggests.”

In fact, Buechner served only for a short time in formal ordained ministry. From 1958 to 1967 he served as chaplain at Phillips Exeter Academy, where he also taught English. At Exeter he had to find new ways to present the Christian story to disaffected teenagers with a budding disrespect for authority. (John Irving was among his early students.) In a way, his career as a Christian writer has been the same ever since: finding ways to tell a religious story to a secular society.

“Every minister should start off with a hostile congregation, I think,” he muses, “because they just don’t accept it all.”

In the preface to Secrets in the Dark, a collection of sermons published in 2006, Buechner writes: “It seems to me there is an Exeter student in each of us, even those of us who are churchiest and most outwardly conforming, who asks the ultimate question, ‘Can it really be true?’ and every time I have ever preached, I have tried to speak to that question.”

IN 1967 BUECHNER MOVED TO VERMONT, where he returned to writing full time. He and his wife, Judy, raised three daughters on Wind Gap Farm, and the daughters and grandchildren are frequent visitors. If Buechner’s life is not quite monastic, it is quiet and reclusive. He does not use email and still corresponds with his readers in longhand. At the height of his career he wrote a book a year, but he no longer is so prolific; his last collection of essays, The Yellow Leaves: A Miscellany, was published in 2008. Asked how he spends his days he says, impishly, “I stare into space.” “I can’t seem to write anymore, unfortunately,” Buechner says. “I hope it will come back.”

Buechner still writes letters, but his diminished productivity is frustrating. After all, this is the man who wrote in his 1992 memoir Telling Secrets: “After 40 years of writing books, I find I need to put things into words before I can believe they are entirely real.”

For Buechner, the process of writing about his life is sacred: “My story is important not because it is mine, God knows, but because if I tell it anything like right, the chances are you will recognize that in many ways it is also yours. ... It is precisely through these stories in all their particularity, as I have long believed and often said, that God makes himself known to each of us more powerfully and personally.”

Buechner turned to memoirs to explore a troubled family past. When he was just 10, his father committed suicide. In his memoirs The Sacred Journey and Telling Secrets, he circles back to this event again and again to explore its significance. “If ever anybody asked how my father died, I would say heart trouble,” he writes. “That seemed at least a version of the truth. He had had a heart. It had been troubled.”

Despite the difficult subject matter, Buechner found joy in writing about his life, especially his youth. “It gives you back a part of your life that you might never have stopped to think about,” he says. His library is filled with mementos of his youthful passions: the Oz books by L. Frank Baum; a glass pair of ruby red slippers; drawings from the Uncle Wiggily cartoons. The Magic Kingdom, as he calls his library, is a place of both seriousness and whimsy. Children’s books are shelved along with the works of Anthony Trollope and Augustine. One wall is filled with rare books he bought in Europe on his honeymoon. Buechner spends most of his days in his study or the writing room that adjoins it. Here are “books I’ve known all my life and love to have about me,” he says, “even if I don’t read them all the time.”

Amid the books sits evidence of his friendships, both real and literary. Next to his chair is a bust of the poet James Merrill. They met at Lawrenceville and remained friends until Merrill’s death seven years ago. On the wall hangs a letter from William Maxwell, a writer whom Buechner much admires and considers underappreciated. A picture of Graham Greene smiles from across the room. Buechner never met the man, but he feels a strong kinship with his work, especially the novel The Power and The Glory. The central character of that novel is an inept and sinful “whiskey priest” who somehow manages to do God’s work. Leo Bebb, the protagonist of four novels Buechner wrote during the 1970s, is a similar character: a charlatan preacher who still bears witness to the presence of God. “It was really the great literary romance of my life,” Buechner says of the four Bebb books. “When I took the pen it was as if there was a hand inside my hand ... I didn’t have to stop and imagine. They were very alive in my head. And very good company.”

Though Buechner’s books generally have been well received, there have been negative reviews. Writing about Treasure Hunt in 1977, Edith Milton commented in The New Republic that Buechner’s characterizations remind one of “those Broadway comedies of the ’30s, in which funny people, easily recognizable from the second balcony by one large but harmless peccadillo, enter, collide, and exit, without major social or dramatic consequences.”

But Buechner’s next novel, Godric, was a finalist for the 1980 Pulitzer Prize in fiction. Dale Brown teaches the book regularly at King College, and believes it will be Buechner’s most lasting work. It tells the story of a 12th-century saint who embarks on a journey of self-purification late in life. Buechner’s fans regularly cite quotes from the book. “What’s prayer?” Godric asks. “It’s shooting shafts into the dark. What mark they strike, if any, who’s to say? It’s reaching for a hand you cannot touch.”

BUECHNER MAY BE uniquely prepared for the quiet life that he now lives.

He never was a man of idle chatter, even at the height of his career, and he does not enjoy analyzing his work in public. He never went on a book tour. He is unlike his late friend Merrill, who was known for heady talk. Buechner prefers to let his writing do the talking. At a 2006 tribute at the National Cathedral, he ended the day by urging the audience to stop talking and appreciate the quiet.

“I have a feeling we have talked enough — that we need silence. Not much — three minutes; to spend three minutes not saying a damn thing. Can we do that? Are we brave enough to do that?”

For a man who appreciates silence, Buechner does not claim to be, at this late stage in his life, engaged in deep reflection. He dismisses questions about his prayer life in the same way he dismisses questions about his writing. Nothing serious, he says; nothing disciplined. It is also notable that the Rev. Buechner does not attend church. He finds most ministers to be playing a role rather than being themselves, a pose he finds intolerable. One of the few preachers he considers “authentic” is his eldest daughter, Katherine, a pastor of a church in northern Vermont.

“Ministers are supposed to say religious things, and they say religious things,” he says. “I always think that at some point in their lives they were moved passionately to become preachers, but that passion has been lost under the clutter of their other ministerial obligations. ... What comes out is not very lively.”

Still, while Buechner may not be a churchgoer, or even a regular man of prayer, he is known for writing eloquent prayers. His son-in-law, David Altshuler, remembers fondly a prayer Buechner wrote for the funeral of his father, John H. Altshuler. Marking his 50th reunion, which coincided with the University’s 250th anniversary celebrations, Buechner offered a reflection that tried to honor both his Christian identity and the school’s diverse population: “Whether or not they call upon his name or even honor it, may [Christ] be present especially in the hearts of all who teach here and all who learn here, because without him everything that goes on here is in the long run only vanity. May he be alive in this place so something like truth may be spoken and heard and carried out into the world. So that something like love may be done.”

WHEN HE IS NOT IN HIS STUDY, Buechner often sits on his patio. Today he is reading The New York Times. A copy of The New Yorker is by his side. He wears a crisp collared shirt, slacks, and a hat, with a button that reads “Jesus loves you, but I’m his favorite.” Up the hill is his wife’s garden, and farther up a grove of trees known for their maple syrup.

The conversation drifts from the Latin quotation on his ring (Vocatus atque non vocatus, Deus aderit, meaning “Invoked or not invoked, God is present”) to his lifelong struggle with doubt regarding whether he thinks about the afterlife. (Not really.) Before long he grows tired of these subjects. Earlier in the day, he confided, “I get tired of my own words, I get tired of my own voice, I get tired of my own patterns of thought,” and now it seems to be coming true. He would prefer to talk about his family or a visitor’s plans for summer break. In other words, he wants to be himself.

“The secret of literary success, I think, is to end up sounding like yourself, which is hard to do,” he says. “It’s as soon as you start writing, or making a speech, you want to sound like what you think is going to sell best, or what people will listen to most acutely, what will remind them most of things they say to themselves.”

The sentiment is captured in King Lear, a play Buechner taught at Exeter and returns to again and again. For a moment, he tries to recall the final lines of the play. He drums his fingers on his leg, tapping out the notes to a half-remembered song. And then it comes to him.

“The weight of this sad time we must obey,” he says, pausing for effect. “Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say.”

Maurice Timothy Reidy ’97 is online editor at America magazine.

No responses yet