$20 million grant supports clean-burning fuel studies

When the U.S. Department of Energy announced a five-year, $777 million commitment to research in clean and renewable energy last April, Energy Secretary Steven Chu said the program would “mobilize the enormous talents and skills of our nation’s scientific workforce.”

At Princeton, that process kicked off in October when researchers from seven universities and two national laboratories met to plan the agenda of the Princeton-based Combustion Energy Frontier Research Center, one of 46 centers funded by the Department of Energy program — and the only one devoted to the combustion of alternative fuels. The center will receive $20 million over the next five years.

Understanding combustion is “an important aspect of the energy equation,” according to mechanical and aerospace engineering professor Chung Law, director of the center, because it could help researchers design and develop efficient, clean-burning fuels and engines.

Chu has told Congress that decreasing America’s dependence on oil and cutting carbon emissions will require “transformational” and “game-changing” advances — the kind of discoveries that win Nobel Prizes. In combustion, that means starting with fundamental science, Law said.

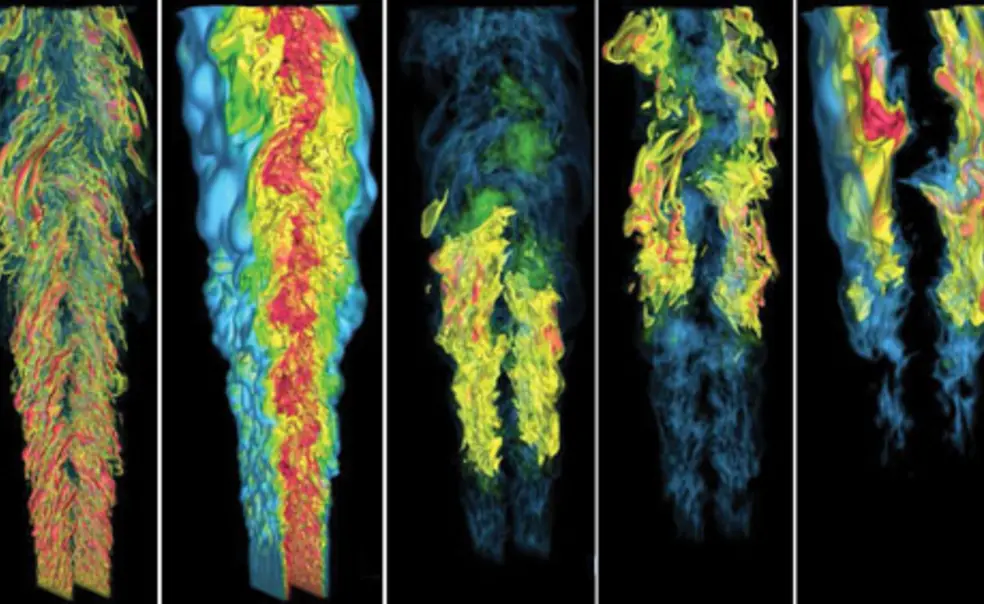

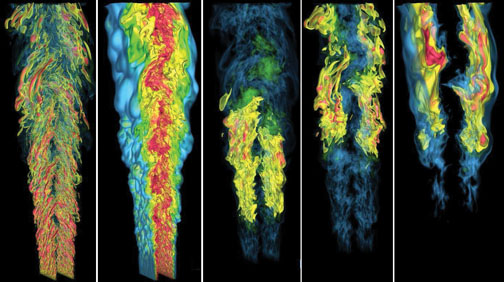

“If you really want to make big improvements, you have to understand the combustion process from the very basics — the chemistry of reactions, the physics of fluid mechanics, and now, of course, the behavior of the biofuels,” he said.

Those fundamentals are complicated because the rate of reaction and heat release from burning a fuel molecule varies with temperature and pressure, according to Emily Carter, a mechanical and aerospace engineering professor and computational science expert who shares the center’s leadership duties. Understanding reactions is important for several aspects of the center’s research, which will examine combustion “from electrons and molecules all the way up to engine design,” Carter said.

The Combustion Energy Frontier Research Center will focus its initial studies on butanol, an alcohol that can be produced from biomass. Law said that the center will use butanol to develop a set of analytic and experimental methods that can be applied to examine the characteristics of a wider range of alternative liquid fuels.

No responses yet