About-Face on Grading?

Faculty to consider ending targets for A’s, relying instead on departmental standards

Princeton soon may abandon its controversial policy aimed at curbing grade inflation, following recommendations by an ad hoc faculty committee that the University drop its numerical grading targets and focus instead on providing better feedback for students’ work and establishing clearer grading standards at the departmental level.

The current guidelines, adopted in 2004, seek to limit A grades to 35 percent of undergraduate coursework. Though they are recommendations only, the targets are “too often misinterpreted as quotas” and contribute to student anxiety and a culture of competition on campus, the committee concluded in a report released in early August. The group was appointed by President Eisgruber ’83 to review the policy.

Eisgruber has endorsed the committee’s proposals, which likely will come before a faculty vote in October. “It’s my strong feeling that we should be known for the quality of our teaching and the distinctiveness of our commitment to undergraduate education, not for the severity of our curve,” he said. “The committee wisely said: If it’s feedback that we care about, and differentiating between good and better and worse work, that’s what we should focus on, not on numbers.”

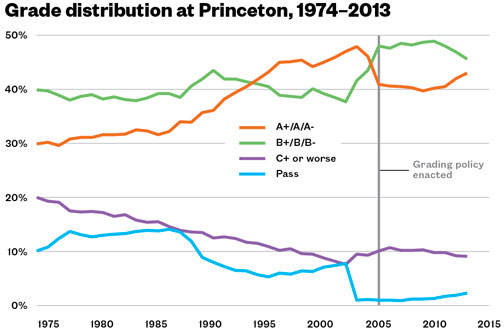

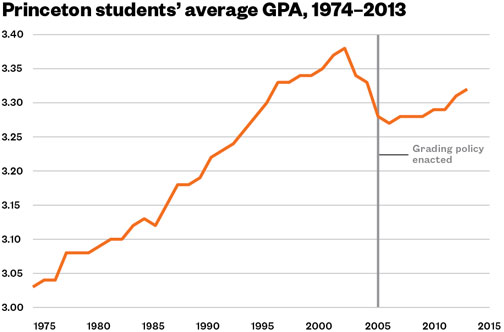

Since the policy was adopted, the percentage of A’s awarded has dropped from 47 percent in 2001–04 to 41.8 percent in 2010–13. As a result, a larger share of grades shifted into the B-range, while the fraction of grades C and below held steady.

Despite student complaints that the “grade-deflation” policy puts them at a disadvantage, the committee found no evidence that it had harmed most graduates’ job prospects or success in gaining admission to graduate or professional schools or winning competitive fellowships. (The exception, the committee found, was ROTC students, whose first assignments are awarded based on GPA rankings.)

Nevertheless, the perception that A’s were in short supply has turned classrooms into pressure cookers, the committee concluded.

Shawon Jackson ’15, president of the Undergraduate Student Government, welcomed the proposals. “I think the shift away from quotas will have a huge impact on the student body,” he said. “It will show that you don’t have to fight with your peers to get an A or A-minus in a course. If you meet the standards that are established from the beginning, you’ll get the grade you deserve.”

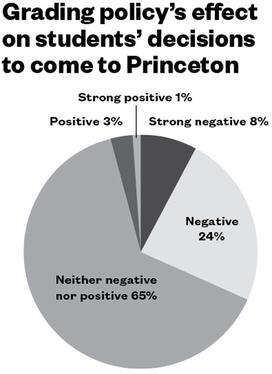

Fear of low GPAs may deter prospective students from attending Princeton, the report suggested. Coaches reported that perceptions of the grading policy handicapped them in recruiting student-athletes, the report said. Janet Rapelye, dean of admission, told the group that applicants and their parents fixate on the grading targets and that the grading policy was the “most-discussed topic” among prospective students at the Princeton Preview days. “The committee was surprised to learn that students at other schools (e.g. Harvard, Stanford, and Yale) use our grading policy to recruit against us,” said the report.

What’s more, the committee concluded, the numerical targets may have been only partially responsible for reversing a pattern of higher grading. After a period of “substantial grade inflation” from 1974 through 2003, the report noted, grades fell sharply in advance of the current policy’s implementation in 2005. The fraction of A grades continued to decline a bit for a few years, then increased between 2009 and 2013 as monitoring of the policy grew more lax.

The fact that the steepest drop in grades occurred in the two years before the policy took effect suggests that sustained conversation about grading may be as effective as numerical targets in keeping rising grades in check, the report concluded. It recommended that departments develop grading rubrics — similar to those created for assessing senior theses — to give students a clearer sense of what distinguishes A-level work.

Rolling back the grading policy would end an experiment that has been hailed in academe as both successful and courageous. When the policy was adopted, Princeton had hoped that other elite schools would follow suit. None of the Ivies did, though Wellesley College in 2004 instituted guidelines that the mean grade for 100- and 200-level classes should not exceed a B+.

An analysis of Wellesley’s guidelines published in The Journal of Economic Perspectives found that, although the policy brought down grades, it also widened racial gaps in grading trends and reduced enrollments in departments most affected by the changes. “Any institution that attempts to deal with grade inflation on its own must consider the possibility of adverse consequences of this unilateral disarmament,” the Wellesley researchers warned.

Princeton’s willingness to take bold actions ahead of its peers paid off in the case of its “no loan” financial-aid policy, Eisgruber said. But in terms of grading, he said, “being out there alone increased the stress around our policy.”

If the faculty committee had found that “there are huge pedagogical benefits to numerical targets, we would have stuck with numerical targets,” he said. “But what they’ve said is that this may be unusual, but it’s not bold in the sense of improving our education in any way.”

“We continue to be bold in doing things that innovate on our campus,” he said, citing the bridge-year program and the University’s commitment to keep tenured faculty in the classroom.

A survey for the committee showed faculty members split on their view of the grading policy (47 percent in favor, 37 percent opposed, 16 percent neutral), with natural sciences expressing the strongest support and the humanities the widest opposition. But the survey found only minor shifts of opinion in the past decade; when asked about their position at the time it was adopted, 50 percent of faculty who were on campus in 2004 reported they had been in favor of the policy, compared with 35 percent opposed and 15 percent neutral.

The committee’s recommendations are “muddled thinking,” said physics professor Daniel Marlow, who said that the targets successfully have steered Princeton away from the inflated grades seen at other universities. “Absent a numerical target, it will be hard to avoid an upward drift,” he said. “I don’t think we can give students high grades just to lower their stress level.”

English professor Esther Schor has long opposed the policy’s “one-target-fits-all” model. “Although these targets were not quotas per se, the dean’s office clearly intended that department chairs implement them, not simply recommend them,” she said in an email. “I feared in particular for junior faculty and graduate instructors, who were most likely to feel pressure (and be pressured) to grade according to targets rather than according to their own best judgment.”

“I’ll be happy to wave it goodbye,” art and archaeology professor Jerome Silbergeld said of the policy. “If all my students deserve good grades, I should be the first one to know that, not somebody else establishing policy from beyond.”

Professor Stanley Katz of the Woodrow Wilson School expressed mixed feelings about the committee’s proposals. While he agreed that the 35 percent cap on A’s was too rigid, he said that grade inflation is “educationally a bad thing” and that if the policy “is to be left to departments, I would describe that as an act of despair — in other words, I think it’s giving up.”

Many expect that grades will creep upward if the faculty votes to abandon the grading targets, although not everyone believes that’s a problem. “I think in the current climate, where our peer institutions have grades that are so far above ours, it’s fine if our grades rise a little bit,” said Clarence Rowley ’95, a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering and chair of the ad hoc committee.

If grade inflation were to become a problem, Rowley said, it might be corrected by discussions between the dean of the college and department heads. “If it does start to get out of control,” he said, “I think those conversations are a better way to rein things in than the numerical targets.”

5 Responses

William E.L. Grossman ’59

10 Years AgoWrong Way on Grading

The following is an expanded version of a letter from PAW’s Nov. 12, 2014, issue.

I am very disappointed by the proposed discontinuance of the grading policy as described in PAW (On the Campus, Sept. 17), and by what seem to me to be red herrings in some of the arguments against that policy.

First of all, it is upsetting that there should be a need for such a policy. It cannot be the case that, even in the highly selected Princeton student body, a Lake Wobegon group in which every student is above average, there should not be a distribution of performances in a course.

One red herring is the idea that Princeton grades are a measure of comparison with other universities. When I graded my students at Hunter College, I did not grade them as if they were at Princeton. How could I? Course grades reflect an assessment of the students’ mastery, broadly speaking, of the material presented to them. The level of that material will properly vary with the capabilities of the students. One would expect that it would be set such that only the very best students would be able to master most of it, and that some minimum effort would be required to achieve a passing grade.

Naturally, that level is not set in a vacuum. From discussions with colleagues at other universities, among other things, one can judge how one’s course level compares to similar ones elsewhere. One can express that judgment in recommendations, written or verbal. The students’ grades, however, can have reference only to standing in the course.

The pedagogical benefit to a student in knowing that standing is considerable, if not the “huge” one that President Eisgruber ’83 seems to require. It is a major factor in telling a student to what extent improvement is needed and how his/her study regimen is working. (In the bad old days, when Princeton accepted any old clodpoll — you only had to ask nicely — our grades were posted anonymously. I found that very helpful.) Contrariwise, uniformly high (or low) grades are of no help to either the student or the adviser.

The idea that the instructor should best know what grade a student deserves, expressed by Professor Jerome Silbergeld in the PAW article, is certainly true. His statement’s implication, that no one else has a stake in that grade, is completely wrong. Course standards are set by the instructor, but Princeton’s reputation as an educational institution is based largely on the perception that its exit standards are high. If those standards are set at a point at which a lesser effort still earns a high grade, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that the students are not being challenged sufficiently. This should be a matter of great concern to the institution and to the students, whose outside assessments depend very much on the perceived quality of the institution.

Another argument that seems to me to be completely beside the point is the one that couples the grading policy to an increase of student stress. The purpose of grades is educational; they are not given to alter the psychological state of the student. Princeton is not a rest home. Moreover, students should be aware that one is competing with one’s peers all of one’s working life. That competition is commonly pass/fail: One person gets the job, or the promotion, or whatever, and the rest do not. How about that for stress? A competition for grades is a relatively benign one — a grade of C will not cost you a job, or make you go hungry.

Finally, there is the astounding argument that the grading policy is bad because it affects the recruitment of students. What kind of student does Princeton want to recruit? Does she want students who are willing to work to grow intellectually, or ones who want the cachet of a Princeton education without the effort? What is the benefit of having more weak student applications? Why lower the University’s exit standard, and ultimately its reputation, to change from an acceptance ratio of one in 10 to one in 11 (or whatever the numbers are)? Astonishing.

What is not surprising is the revelation that places like Yale and Stanford are using the current policy as a recruiting tool “against us.” Well, of course; and they probably can get football players that Princeton cannot. Surely Princeton can use their grading policies against them. Do you, as a student, want fellow students who are intellectually curious and active, or do you want to sit in lectures where you can’t see over the heads of the athletes in the front row (here I am talking only about athletes at places like Yale and Stanford – not Princeton)?

Seriously, and basically, the reasons for a change in policy seem both weak and wrong-headed. The result will be that Princeton’s academic quality — and reputation — will be lowered, not enhanced. It is a move in the wrong direction.

Jay Granzow ’93

10 Years AgoDownsides of Grading Policy

My wife and I both read “About-Face on Grading?” (On the Campus, Sept. 17) with concern about the faculty committee’s finding that there was no evidence the grading policy has harmed graduates in seeking a job or applying to graduate school. My wife is an attorney at a Fortune 500 company who previously had worked at a large U.S. law firm, and I am an associate professor of surgery at UCLA. In our experiences, it’s been absolutely clear that grade deflation hurts applicants. Whether it’s law firms hiring attorneys or faculty ranking medical students for residency positions, grades matter. Sure, we and everyone else think those reviewing résumés or transcripts should look at each institution’s grade distribution and weigh accordingly. But, in practice, this doesn’t happen. Applicants with higher GPAs tend to rank higher. A 3.7 GPA simply looks better than a 3.3 GPA when reading through hundreds of prospects’ files. This has been confirmed in a recent article by researchers from UC Berkeley and Harvard Business School.

Like it or not, a school that deflates grades using “grading targets,” another name for curves, hurts its students’ chances. And anyone who ever has taken a class with a curve knows that a curve also fosters negative competition for the top marks. While everyone would like to see a uniform grading standard among different institutions, it simply isn’t going to happen. Do Princeton students the favor: Dump the curve, and let the professors give out the marks they think the students deserve.

David W. Pratt ’59

10 Years AgoGood Grades vs. Real Learning

I am dismayed by the letter from Jay Granzow ’93 and his wife seeking change in the grading policy at Princeton (Inbox, Oct. 22). Our student “customers” and their families are putting huge pressure on schools and their faculties to give good grades so they can get into good schools and get good jobs, and real learning is suffering as a result. If it is normal for law firms and medical-school faculties to focus on GPAs for hiring lawyers or filling residency positions, then it is not surprising that our political, business, and health-care institutions are in such bad shape. When will such institutions learn to focus on other, more meaningful accomplishments, such as apprenticeships and research experiences that teach problem-solving skills and prepare our students to meet the challenges that lie ahead? It is time that parents, admission officers, and employers realize that this focus on GPA and other quantitative measures of “success” is destroying the quality of the educational experience that we want our children to have.

I applaud my alma mater for working hard to prevent continued grade inflation and to ensure that the value of a Princeton education is not diminished.

Stewart A. Levin ’75

10 Years AgoDownsides of Grading Policy

After reading the recent “Report from the Ad Hoc Committee to Review Policies Regarding Assessment and Grading,” I was most saddened to read that a “common theme was that the grading policy harms the spirit of collaboration,” illustrated by this passage:

“I have experience[d] multiple negative effects from the grading policy. Because of grade deflation it has been extremely hard to find any kind of collaborative environment in any department and class I have taken at Princeton. Often even good friends of mine would refuse to explain simple concepts that I might have not understood in class for fear that I would do better than them. I have also heard from others about students actively sabotaging other students’ grades by giving them the wrong notes or telling them wrong information. Classes here often feel like shark tanks. If I had known about this, I very probably would have not attended Princeton despite it being a wonderful university otherwise.”

Such a shame! One of the nicest memories of my Class of 1975 days was seeing how quickly my classmates and I sloughed off our high school attitudes of competing over each one-hundredth-of-a-grade-point as we dived into a world of sharing the knowledge and concepts we came to learn, simply for the beauty of learning and applying new ideas and passions. And all this in an environment with only about 30 percent of grades being A’s.

Christine Adams Osborn ’87

10 Years AgoDownsides of Grading Policy

I urge the University to end the grade-deflation policy. In 2011, when my daughter was considering Princeton as her No. 1 choice, we attended an information session in Greenwich, Conn., where she had the opportunity to meet with alumni and admission representatives. I asked if the grade-deflation policy would be continued, since it appeared from our multiple visits to the school that it was creating an overly competitive culture among the student body. While the admission representatives commended the policy, the alumni who had students at Princeton overwhelmingly responded negatively and solidified our perspective.

As a result, she did not even apply to Princeton because she wanted a school that fostered a collaborative and supportive approach to academics, rather than one that was cutthroat. One of the best parts of Princeton was learning from peers — which, in my opinion, is stifled with the grade-deflation policy. Please end it.