The senior-thesis requirement is Princeton’s great leveler, a lonesome valley nearly every senior must walk on the road to graduation. It can be a curse or a blessing, usually both, sometimes in the same afternoon. All who have gone through it have war stories to tell. Here’s mine.

Professor emeritus Arno Mayer was my adviser in 1983 when I wrote my thesis about relations between the British Labour Party and the United States in the years just after World War II. Mayer may have been one of the world’s great scholars of modern European history, but he was an indifferent adviser to me, telling me later that he never read the draft chapters I gave him because I had printed them on extra-wide, green-lined computer paper. One winter afternoon I needed to see him, and I found Professor Mayer as he emerged from Dickinson Hall wearing a beret and a long woolen scarf and chewing on a piece of candy. He told me he was late for a meeting, and that if I needed to talk I would have to walk with him.

We crossed McCosh Courtyard with long strides, stopping just outside the entrance to Firestone Library. After delivering a benediction, he put out his hand and I stuck out mine in return, thinking that he wanted to shake it. Instead, he put a small scrap of paper in my open palm, closed my fingers on it, patted my shoulder, and walked away. As he disappeared into the lobby, I looked down at the gift he had given me.

It was a Tootsie Roll wrapper.

Writing a thesis may be the capstone of one’s independent work at Princeton, but mine was going to have to be more independent than most. In the end, though I enjoyed writing my thesis, I cannot say that it influenced my decision to become a writer. A bound copy still sits on a shelf in my office, but on the few occasions I have tried to reread it I have slammed the cover shut in embarrassment. It reads, to be honest, like student work.

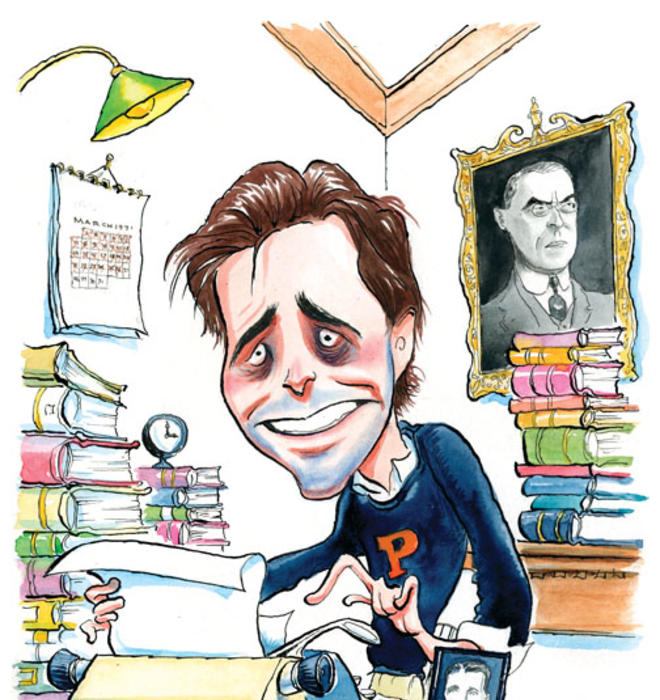

Others, however, can point to their thesis as a defining moment in their lives. The most famous stories are well known. Wendy Kopp ’89 used hers to outline the organization that became Teach for America. Jack Bogle ’51 wrote about mutual funds and went on to found Vanguard, the largest mutual-fund company in the world. Some alumni have turned their theses into books: Barton Gellman ’82 wrote about diplomat George Kennan ’25, published Contending with Kennan two years later, and launched a career as a Pulitzer Prize-winning (twice) journalist. A. Scott Berg ’71 decided he wanted to write about literary editor Maxfield Perkins when he was still a freshman and worked throughout his undergraduate years with Professor Carlos Baker *40. He turned his research into a prize-winning thesis, then spent another seven years expanding it into Max Perkins: Editor of Genius, for which he won a National Book Award.

“Even though Princeton only promised me an education,” Berg says, “it also delivered a career.”

Over the last 87 years, more than 63,000 theses have been submitted, all of which are housed at Mudd Library — except for approximately 300 discovered in the 1990s to have gone missing when they were kept on the open shelves at Firestone. One of those missing theses belonged to Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito ’72, who wrote about the Italian constitution. Fortunately for posterity, his adviser came forward with a copy when Alito was nominated to the Court. Beginning with this year’s seniors, the library will only save electronic copies (though some departments will continue to require bound theses).

Theses have taken many forms and covered almost every topic imaginable. Topics close to home are perennials; at least 482 theses over the years have addressed Princeton in some manner. The two most popular individual subjects are favorite sons: Woodrow Wilson 1879, the subject of 56 theses, and F. Scott Fitzgerald ’17, close behind at 53.

Jean Faust Jorgensen ’76 was one of those who chose Fitzgerald as her subject, and her 756-page thesis holds the record as the longest ever submitted. Jorgensen, however, insists that she has gotten a bum rap; her thesis was a compilation of short stories by Fitzgerald published in various magazines, with a 25-page analysis at the front. “So, in other words, F. Scott Fitzgerald is the author of my thesis,” she explains. “I simply wrote the introduction.” At the other end of the scale, the three-page thesis submitted by Gianluca Tempesti ’91 is the shortest on record. The electrical engineer explained in the thesis that he had wanted to write about “Opto-Electronic Integrated Circuits,” but was thwarted when computer chips he needed did not arrive until a few weeks before his deadline. He expressed hope that he would continue to work on the idea. “The testing,” he wrote apologetically, “has just begun.”

It is usually a fool’s errand to search a senior thesis for clues about its author’s future beliefs, but that does not always dampen the temptation to play “gotcha.” During the 2008 presidential campaign, conservative pundits pored through the thesis submitted by Michelle Robinson Obama ’85 — on “Princeton-Educated Blacks and the Black Community” — for anything that might paint her as a militant radical. Donald Rumsfeld ’54 wrote about President Harry Truman’s seizure of the steel mills in 1952 and offered eloquent warnings against executive overreaching during a national crisis, words he might have felt differently about when serving as defense secretary during the Iraq War 50 years later.

Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor ’76, who wrote about Luis Muñoz Marin, the first elected governor of Puerto Rico, says the project helped hone her cultural identity. “Some part of me needed to believe that our community could give birth to leaders,” she wrote in her recently published memoir, My Beloved World. “Of course I knew better than to let emotion surface in the language and logic of my thesis; that’s not what historians do. But it kept me going through the long hours of work.”

Angela Ramirez ’97, chief of staff to Rep. Ben Ray Luján (D-N.M.) and former executive director of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, recommends caution when trying to hold someone accountable for a college paper assembled decades earlier under less-than-optimal conditions. “You’re writing it when you’re sleep-deprived and looking for a job and somehow, magically, you’re supposed to write this masterpiece,” she points out, referencing her own thesis on the 1965 Immigration Act, which she admits she hasn’t read in 16 years. For every thesis that gets published, a thousand more are turned in and forgotten.

“The best theses are more ambitious than used to be the case decades ago,” Professor Nancy Weiss Malkiel, former dean of the college, tells PAW in an email, “but I think the overall quality — best and least good — is pretty much the same.”

Contrary to the theory that the thesis was created to give seniors something to complain about, its purpose was to get them out of the classroom and into the library, the archives, and the field. Most of the credit for the requirement belongs to mathematician Luther Eisenhart (later dean of the graduate school), who in the early 1920s served on a faculty committee considering whether to reinstitute honors courses, which had been discontinued during World War I. Rather than carve out a special curriculum for top students, Eisenhart recommended lightening the course load for all upperclassmen and requiring everyone to devote the extra time to independent work.

“The theory of the plan,” he later wrote in PAW, “is that at graduation a student shall have gained at least a moderate mastery in the field of knowledge he has chosen for his main effort; that his mastery shall mean more than a mere assemblage of facts stored by memory from the courses taken; that he shall have gained by his method of study an appreciation of the relations of various parts of the subject, shall have organized his knowledge, and shall have developed the power of expressing his conclusions in a clear and convincing manner.”

Princeton’s “Four Course Plan” (so named because of the number of courses upperclassmen would take per semester) was hugely controversial when it took effect in 1924 and for years afterward. Eisenhart, however, had not defined what form the independent work should take. In 1926, the English and biology departments first required seniors to write theses, and other departments quickly followed. Today, every student seeking an A.B. degree must write one, although departments have different rules about lengths and deadlines. Though all B.S.E. students are required to do some form of independent work, only the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering requires a thesis.

Virtually everyone who has gone through the experience remembers it with pride and a bit of a shudder. As for many before and after him, one of the first things that comes to mind for James A. Baker III ’52, a Cabinet secretary under two presidents, is the memory of “so many cold winter nights in a green metallic carrel in Firestone Library sweating it out. I think that was a really important part of the Princeton experience.” To the chagrin of many, those carrels recently were torn out as part of the library’s renovation, to be replaced by a combination of open carrels and lockers.

Given that one of the purposes of the thesis is to engage students in areas they find interesting, it is no surprise to discover, for example, that Brooke Shields ’87 wrote about the films of director Louis Malle (one of which she had acted in) or that Chris Young ’02, who has pitched for several major-league teams, chose a topic having to do with baseball. But a thesis topic doesn’t necessarily foretell a career. Carl Icahn ’57 became a billionaire business magnate, but he majored in philosophy and has described work on his thesis — “The Problem of Formulating an Adequate Explication of the Empiricist Criterion of Meaning” — as “exhilarating.”

Many enduring lessons are learned between the lines, so to speak. Ralph Nader ’55’s thesis on Lebanese agriculture would seem to have nothing to do with his subsequent career as a consumer advocate, but he has said that his research exposed him to the problems faced by rural workers. In a similar vein, George P. Shultz ’42 spent two weeks living with a poor family in the mountains of North Carolina while working on his thesis about the Tennessee Valley Authority. Spending time in the field taught him several lessons that would serve him well as a professor and as secretary of labor, treasury, and state — perhaps the most important of which was to respect his subjects. “There are,” he found, “a lot of innately capable people who are working hard doing something constructive.” Sitting on the front porch of his host family’s rundown farmhouse, he learned how to conduct an interview and, in talking to people affected by large government programs, came to appreciate that official statistics about those programs were not always as precise as they looked.

Writing a thesis can teach a student how to work — or how not to work. Berg admits that he spent so much time on his research that he had nothing written a month before his deadline. “You’re going to get a book out of this,” he remembers his adviser warning him, “but you’re not going to graduate.” Holing himself up at Cottage Club, Berg managed to crank out 10 pages a day for four weeks and emerged with a 262-page thesis.

Paul Volcker ’49, the future Federal Reserve chairman, wrote his thesis about ... the Federal Reserve. But he, too, found himself halfway through his last semester with little to show for it. To jolt him out of a bad case of writer’s block, Volcker’s adviser, Professor Frank Graham, suggested that he write first and edit later. That is what Volcker did, setting down a more or less stream-of-consciousness chapter each week on long legal pads, submitting them to Graham on Fridays and getting corrections back the following Mondays. He graduated summa cum laude.

Not only did Volcker find a subject that would occupy much of the rest of his career, he found a way of tackling big projects, which he calls “procrastinate and flourish.” As he told a biographer years later, “I found that it worked, so I never changed. Besides, it gave me time to think and to get it right.”

Josh Kornbluth ’80, on the other hand, might be the poster boy for the “just procrastinate” camp. He still has not finished his thesis, although fortunately for him, there is no limit to how late one can be submitted. Last year Kornbluth, an actor and comedian, finally submitted a monologue from his show Citizen Josh, but he says it was rejected by the politics department. “I will write some more standard-thesis-y-type stuff, which I will then append to the script of the theater piece,” he says in an email, “and if I pass, I will finally graduate from Princeton! My mom will be so pleased!”

One might say, then, that the point of a thesis is the journey, not the destination. Again and again, alumni return to this point.

As a student, Sally Frank ’80 started a long and ultimately successful legal battle to force the all-male eating clubs to admit women. She wrote her thesis on “Strategies and Tactics Used by the Women’s Movement to Create Radical and Reformist Change,” but says that the litigation had little influence on her thesis or her becoming a law professor at Drake University.

“What I found most interesting was doing original research,” she says, recalling trips to the Library of Congress and to the Smith College archives, where she was able to examine Susan B. Anthony’s papers. “That piece, where I could actually handle a piece of history — that stuff is pretty exciting.”

So it was with me. I managed to get a small stipend from the history department that enabled me to visit Oxford’s Bodleian Library, where former Prime Minister Clement Atlee’s papers are held. There I found gems that had little to do with my thesis topic but fascinated me nonetheless — including a letter from Winston Churchill outlining what became his Iron Curtain speech, and another letter urging Indian independence, written neatly in green ink and signed, “M.K. Gandhi.” I learned the challenges and rewards of writing a small book. I learned to set my own deadlines and stick to them. I learned something about editing. And I learned how much I loved to study history.

“It’s the work that needs to go into it” that makes the thesis important, believes Ramirez, the Congressional aide. “It’s thinking about something in an intense way and then moving on it.” As Shultz says, those often unpleasant months serve a purpose because the finished product “puts you on your own to identify something worth working at, doing some research, pulling it together, and presenting a product.” He, Berg, and several others have endowed scholarships so that other students will have the same opportunities they had to do independent research.

The seniors who have just emerged from the bowels of Firestone or shaved their thesis beards have good reason to feel relieved, but they also should be grateful. The words I wrote 30 years ago gather dust on a shelf. What I learned while writing them, however, helps me nearly every day.

Mark. F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

1 Response

Peter Bogucki

10 Years AgoEngineers write theses, too

In an otherwise excellent feature on the senior thesis (May 15), PAW perpetuates the misconception that very few engineering students write a thesis, stating that the requirement is confined to civil and environmental engineering.

In fact, a thesis is also a requirement in chemical and biological engineering and operations research and financial engineering, although these departments have a rarely used option to do a one-term project plus an extra departmental course. Electrical engineering recently has made a senior thesis mandatory, effective with the Class of 2016. In mechanical and aerospace engineering, many students do either a senior thesis (done by a single student) or a senior project (done by a group of students, such as building a working jet engine), while others organize their independent work by doing multiple one-term projects. Many B.S.E. computer science students do senior theses as well.

Combined with design courses that have substantial self-directed projects, almost all B.S.E. students do as much independent work as an A.B. student, the major difference being that in some engineering departments, there is greater flexibility in how it is structured and how it articulates with the rest of the curriculum.