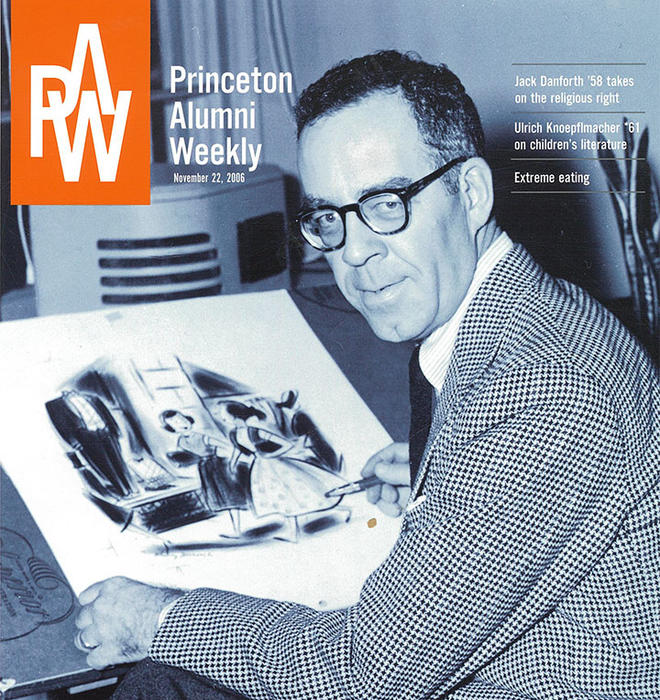

One of the secrets to the long success Whitney Darrow Jr. ’31 enjoyed as a cartoonist and illustrator, in addition to his elegant drawing style and dry wit, was that he so resembled the people he drew. The well-educated child of a well-to-do family, an avid golfer and traveler, and a longtime resident of suburban Connecticut, he was in many ways himself one of the upper-middle-class, decent yet worldly businessmen whom he so gently but incisively satirized for almost half a century in the pages of The New Yorker. He even kept his studio for many years near the Saugatuck train station, the better to catch the train into Grand Central with his Cheever-esque neighbors.

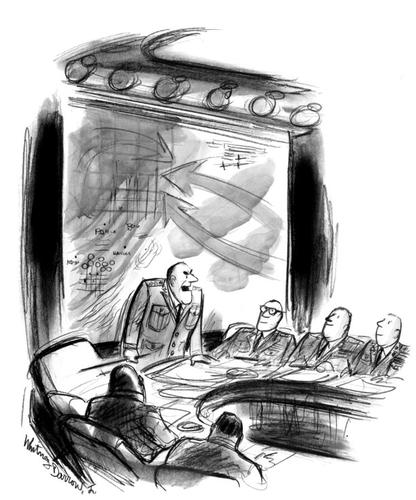

Darrow died in 1999, but his family recently donated more than 1,000 of his original drawings to Princeton, where they are housed in the Rare Books and Special Collections reading room at Firestone Library. The gift — which follows a smaller donation of his work made soon after his death — includes 325 New Yorker cartoons drawn between 1936 and 1982 and 746 drawings for 18 books that Darrow illustrated, including Louise Armstrong’sA Child’s Guide to Freud (1963) and Johnny Carson’s Happiness Is ... a Dry Martini (1965).

A Princeton native, Darrow was the son of Whitney Darrow 1903, who was business manager of PAW and a founder of the Princeton University Press. Young Darrow was a born cartoonist, and from his earliest school days he would decorate his class books with doodles. Nevertheless, Alastair Cooke reported in an appreciation of Darrow done in connection with a 1999 Firestone Library exhibition that Darrow lacked the confidence to submit his work to the undergraduate humor magazine, the Princeton Tiger. A friend finally persuaded him to slip a drawing under the door of the magazine’s editorial office. It was accepted, and after Darrow became the Tiger’s art editor, he changed his major from history to art. Honing the wit that later would enliven his work at The New Yorker, he also wrote a humor column for The Daily Princetonian.

Though he graduated in the middle of the Depression, Darrow appears never to have considered a career path with more job security than that of magazine cartoonist. Cartoon-ing, says his daughter, Linda Darrow, “is all he ever did,” and he did it with the diligence of a professional. After graduation he attended classes at the Art Students League in New York, studying under the great American painter Thomas Hart Benton, among others, and submitted drawings to popular magazines such as Judge, Life, and College Humor before his first cartoon was accepted by The New Yorker a year and a half after he left Princeton. Though Darrow soon was under contract to the magazine and eventually produced 50 cartoons for them a year (more than 1,500 in total, between 1933 and 1982), he continued to take art classes.

That habit of constant practice would stay with him for life. Long after he became successful, Darrow would carry a small sketch pad and draw people wherever he went. Whether working in New York or, later, in Connecticut, he would rise at 6 a.m., exercise, eat breakfast, and then go to his studio — invariably dressed in a sports jacket and tie. “He was the only person I’ve ever known who worked every day,” his daughter recalls. Unlike some of his colleagues, who turned the job over to an editor, Darrow also wrote the captions for his cartoons. Fellow cartoonist Henry Martin ’48 says that Darrow’s work inspired him to draw for The New Yorker, as well.

Darrow’s artistic style and humor, all the more piercing for its subtlety, proved a perfect fit for The New Yorker at mid-century and beyond. “He has an essentially benevolent view of humans,” Cooke wrote of Darrow, “and, as with Damon Runyon, even his villains ... are only pretending to be in charge; they are transparent, and they are adorable.”

Images courtesy Princeton University Library, Rare Books and Special Collections

No responses yet