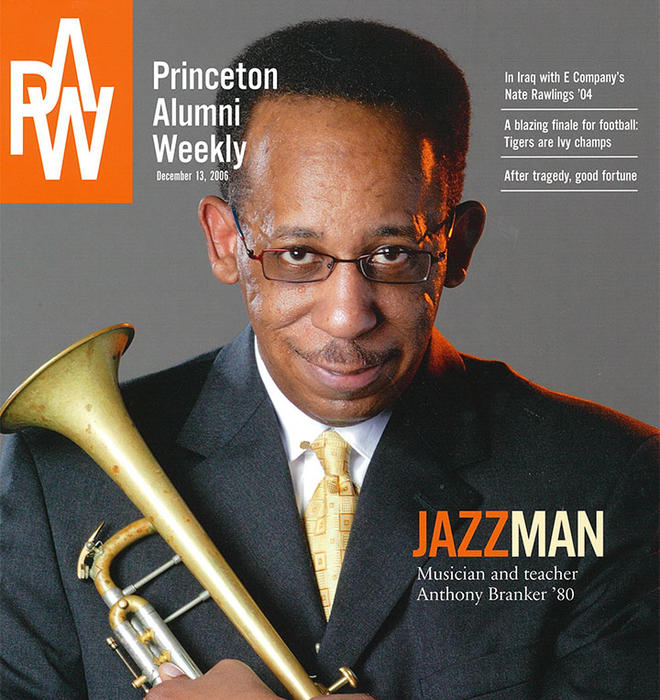

Improvisation is the jazz musician’s calling card. As a veteran trumpeter in the jazz clubs of New York City and the conductor of student ensembles all over the world, Anthony Branker ’80 knows a thing or two about improvising. But even he was not prepared for what he found when his wife, Lisa, summoned him to the basement of their home near Princeton after a heavy rainfall in October. The sump pump had failed, and the place was flooded.

“My heart just sank,” says Branker. “The covers and liner notes of old records were a soggy mess. And I had all these old issues of DownBeat, JazzTimes, Jazziz, and some other, scholarly journals. I was happy that most of the DownBeats were saved, because they go back to when my father got a subscription in the late 1960s. But the rest were under water and ruined.”

The loss came at a particularly bad time, just as Branker was preparing to take five members of the Princeton University Jazz Composers Collective to Estonia. For Branker, the tour was to be a triumphant return: He’d spent the previous fall at the Estonian Academy of Music in Tallinn as a Fulbright fellow, composing, conducting, and mentoring the eager students there. The Princeton quintet had been scheduled to play three shows, but would wind up playing more, including an appearance on the Estonian equivalent of the Today show. They would perform in a Tallinn nightclub and at the Academy itself, giving the premiere performance of “The Eesti Jazz Suite,” which Branker had composed during his residency there.

But before all that could happen, the Brankers had to deal with the mess in their basement. They put a huge Dumpster in the driveway and set about filling it with clothes, furniture, and sodden piles of papers and possessions. Then, with a serenity born of hard knocks and inborn grace, they moved on.

Cleaning up “gave me a chance to go back and look at my life,” Branker says, “because I’m finding stuff from one of my first teaching jobs ... and little cards that students have sent throughout the years.” The cards and notes took Branker back through a career that has inspired musicians of all levels, from high school students eager to learn their first Charlie Parker solo to some of the top pros in the business.

Beneath Branker’s mellow exterior are extraordinary focus and energy. In Tallinn, he used his spare time to write 32 works for small jazz groups, 24 of which he has slated for three more albums. Last January he and his band, Ascent — which includes pianist Jonny King ’87 — released Spirit Songs, a mesmerizing set of eight original Branker compositions. Some pay tribute to idols like Miles Davis (“Sketches of Selim”) and John Coltrane (“J.C.’s Passion”), while others explore his family’s island roots. “Parris in April” is a lovely, lyrical tribute to his daughter, Parris, whose arrival in April 12 years ago presented him with a song title too delightful to pass up. Listening to Spirit Songs, the listener gets a strong sense of Branker’s quiet but deeply felt spirituality. “Being religious is different from being spiritual,” he says. “But a sense of connection with God or with a higher being, a higher source — however one wants to define that — is really integral to who I am and everything I try to do.”

Since Branker’s return to Princeton in 1989 as the part-time director of the Concert Jazz Ensemble, he essentially has built from scratch a program that is the envy of all but the top professional music schools. “Princeton jazz under Tony Branker’s direction is a model program for teaching jazz in a university setting,” says Chris Chafe, a music professor at Stanford who sits on the Princeton music department’s advisory council. “Across all the stages, lectures, and late-night sessions, it’s tremendous for the students who take part.”

Officially, as music department chairman Scott Burnham points out, “there is no Princeton jazz program with a capital ‘P.’ We have everything but.” Branker, he says, teaches courses, leads ensembles, publishes occasional papers for jazz educators, and still manages to compose, record, and work on a doctorate in education at Columbia.

Most schools have one, or at most two, jazz groups. Princeton, under Branker, has six this year. There is the Concert Jazz Ensemble, with 21 musicians; a “Swingtet”; an Afro-Latin Ensemble; an Ornette Coleman Ensemble; a Jazz Vespers Ensemble; and the Jazz Composers Collective. Over the years Branker has directed an ever-changing variety of small groups, each delving into a different area of jazz, such as the music of New Orleans or Ellington/Strayhorn or fusion. Over the last seven years, two ensembles have won top awards in the DownBeat student music competition. On Oct. 14, after just four weeks of rehearsing twice a week, the Concert Jazz Ensemble presented a concert of music by Count Basie in Richardson Auditorium. “The kids were swinging hard,” Branker says. “Basie would have been proud.”Branker on stage, dressed in a natty suit, baton in hand, is a man possessed. “The atmosphere at those concerts is like no other concert on this campus,” says Burnham with a chuckle. “Tony’s got this whole different kind of charismatic energy that’s vastly entertaining. There’s always a monologue, and these guys in the audience seem to know him and interact with him. It’s like a home-field sports audience. I was surprised because I’ve sat next to him at faculty meetings and know how quiet and soft-spoken he can be. ... He comes out on the stage and it’s almost like watching Johnny Carson come out or something.”

To appreciate what Branker has accomplished at Princeton, consider that when Jonny King was a student in the mid-1980s, there was one jazz survey course offered and not much performance-wise beyond a large student ensemble that played mostly classic big-band music. “It wasn’t all Glenn Miller, old-fashioned stuff,” says King. “Some of it was modern. But it just wasn’t the stuff I was into.” As a musician eager to work as much as possible, King had to fend for himself, either by traveling to Greenwich Village or Trenton or New Brunswick to find gigs or recruiting New York musicians to come down and play in the student pub or the eating clubs. “They’d get a couple of hundred bucks and we’d feed them,” he says. There are still students working the way King once did, though now it’s in addition to the thriving scene Branker has created. Drummer Chuck Staab ’07 is playing three and four nights a week, often in Philadelphia, while alto sax player Irwin Hall ’07 has a regular gig with the Oliver Lake Big Band.

“I really didn’t know how good the program was until I left,” says Marissa Steingold ’98, who sang with the University’s Monk/Mingus Ensemble before going on to study jazz singing at the New England Conservatory. She now works in Los Angeles as a studio singer, recording material for movies, television, and commercials.

“He’s the best rehearsal director I’ve been around,” says Staab. “He’s got a great sense of humor and runs [the ensembles] like a big family.”

Though he demands professionalism from his students, Branker also understands that most of them are not going to be working musicians. “He was very supportive of the fact that I was pursuing both music and engineering,” says Keigo Hirakawa ’00, who played piano at Princeton. When Hirakawa moved to Cornell to pursue a Ph.D., he helped run the jazz program there. After getting a graduate degree in jazz piano at the New England Conservatory, Hirakawa now considers himself to have two equally important careers, one as a musician, the other as a postdoctoral researcher in statistics at Harvard.

Above all else, Branker sees himself as a teacher. That’s a result of a nasty surprise he got back in 1999, when he had a seizure and collapsed in the music building. Doctors said he had an arteriovenous malformation, or AVM — “sort of tangled blood vessels in the brain,” Branker explains. To repair it, he underwent several surgeries. After the final craniotomy he was unable to play for six or seven months — long enough to lose his spot in the Spirit of Life Ensemble, the group he’d been playing with for years. He was hired full time at Princeton in 2000.

It’s in education that Branker feels he “can make my biggest contribution: to excite students and to get them to learn a little bit about the tradition, get them to think about the creative process.” He has led student groups in Japan, Germany, Israel, and all over the United States. He has continued to go back to Piscataway (N.J.) High School to help with summer band camp at his old high school, and he makes teaching visits to the independent Bullis School outside Washington, D.C., where his former trumpet student, Cheryl Terwilliger ’92, teaches music and leads several jazz ensembles. “He’s one of my idols, someone who made a great role model for me wanting to be a teacher,” Terwilliger says.

Branker’s own musical education began in Plainfield, N.J., and Piscataway. His father was a business agent for the garment workers union in New York, his mother a medical secretary. Though she had a nice voice in the church choir and he played some pop tunes and calypso on harmonica, the Brankers were not the sort of family that sits around the living room playing music every evening. It was only later that Tony learned of the family’s deep musical roots: An uncle, Rupert Branker, was the piano player and musical director for the Platters; a cousin who lives in Barbados, Nicholas Branker, is a bass player, writer, and producer who was nominated for a Grammy; and yet another uncle, Roy Branker, had collaborated with the composer and arranger Billy Strayhorn.

Young Tony wanted to play drums, but was persuaded by friends that the trumpet was the cool instrument. His first horn was a little school rental, which inspired in him a mixture of excitement and fear. “I was really fascinated by it,” muses Branker. “I was also scared of it because it was really difficult to get a good sound out of it.”

When he was a sophomore in high school, he went to his first live jazz concert, featuring the Maynard Ferguson Big Band. “I just was floored by the spirit, the precision, the passion that the band played with,” recalls Branker. “They had this amazing trumpet section and it made me say, ‘Yeah, I really want to pursue this jazz thing.’ ”

He started listening to jazz records — above all to trumpeters Miles Davis, Woody Shaw, and Freddie Hubbard — and his love for the music grew exponentially. “Those were my Big Three,” he says. “The thing I loved about Miles was just his sense of lyricism, the beauty of his sound, his use of space, and just his being aware of creating great drama in a solo, largely by that sense of space. Whenever I get a chance to turn kids on to music, the album I always say they should check out is Kind of Blue.”

In the summer before his senior year of high school he began practicing five and six hours a day. “I had to work at it,” he says. “People talk about gifts. I think my gift was that I was persistent.” He also spent time each summer at jazz camp at Towson State University in Maryland, where the Stan Kenton Orchestra was the band-in-residence, and a pioneering educator named Hank Levy was building one of the very first college jazz programs in the country. When two of his best music buddies from high school went off to Towson for college, Branker nearly followed them, with the goal of majoring in music and mathematics. But when word came that he got the financial aid he needed to attend Princeton, he quickly changed course. At Princeton he did all the preliminary course work necessary to major in math — just in case his parents would not allow him to major in music — but he persuaded them that there was more to music than just the tough life of a touring musician.

The mid-1970s jazz scene he found at Princeton was sketchy. Even Stanley Jordan ’81, the guitar wizard who’s probably the best-known Princetonian in jazz, came not for the jazz but for the computer music. Alto sax player Bennie Carter would come every three years to lead the Concert Jazz Ensemble. But there wasn’t much in the way of an organized program until Branker returned to Princeton in 1989.

At the time, the ensemble was nothing more than a student club. It had no outside funding, which meant that the band had to find paying gigs to support itself and pay Branker. Indeed, his full-time job from 1986 to 1996 was teaching at Ursinus College in the northeast suburbs of Philadelphia. That overlapped with his job playing trumpet with the Spirit of Life Ensemble, which he still recalls as a highlight of his career. The group toured the world and for five years had a Monday-night residency at Sweet Basil in Greenwich Village; it was not unusual for the biggest names in the business to come by and sit in.

“I made about 80 percent of those shows,” says Branker. “It was tough because we had a band rehearsal at Ursinus that ended at 7. I’d jump in the car and get there just in time for the 9 o’clock hit.”

For all the things that might work against Branker’s turning Princeton into a jazz mecca, it’s lucky that the University is near New York City and all the great musicians working there. Most university jazz programs are built around a single figure and rely on adjunct teachers who come in to teach the other instruments. There’s Paul Merrill up at Cornell, Willy Ross at Yale, and Branker’s old high school bandmate, Glenn Cashman, who was at Towson and has been the one-man jazz department at Colgate since 2001.

The fact that exceptional musicians can be attracted to the classroom is due partly to the time-honored tradition of jazz masters passing on their wisdom, but it also hints at a sad irony: Though the music has come to be taken more seriously as art, it has lost some of its commercial viability. Long gone are the days when Louis Armstrong or Count Basie could pack their bands into a bus and travel coast to coast, knowing that in every city there would be packed clubs awaiting them.

“Creative music generally isn’t very commercial. That’s always been a hard fact,” says Jeff Penney ’83, who played drums while an undergraduate and has continued to support jazz in a variety of ways, including running his own independent record label, Sons of Sounds, on which Spirit Songs appears. “Recorded music in jazz is more of a calling card for the musician, something to document their writing and their playing.” He notes that, like Branker, most of the artists on Sons of Sound are involved with musical education. “My view was that if they are donating their time to work with kids, maybe I can donate some of my time and help them with their business career.”

Penney, who is a managing partner at Merrill Lynch in New York, serves on the music department’s advisory council. He also supports The Commission Project, a foundation that pays established jazz composers to write music expressly for student groups. Through that program, two years ago sax giant Jimmy Heath wrote “For the Love Of” for the Jazz Ensemble, and last year Ralph Bowen, who teaches saxophone at Princeton and plays on Spirit Songs, wrote “Little Miss B” for the same group. Branker has been on both sides of The Commission Project equation, composing several pieces recently for his old high school and conducting “Little Miss B.”

Of course, jazz, like the blues and gospel, comes with a lot of baggage, most of it growing out of slavery and racism. Branker explains that in the 1920s “there was this whole primitivist myth of the noble savage with inspiration coming from God. [The idea was that] these musicians don’t know what they’re doing, but they’re creating these great works of art, and God bless them for doing that.” When asked if jazz deserves the same sort of academic scrutiny as, say, the music of Beethoven or Bach, staples whose presence in a university curriculum no one would think to question, Branker doesn’t quite bristle, but it’s not hard to feel how tired he is of the question. He responds: “My question would be: Why wouldn’t it? When you improvise, you’re not so much thinking on your feet as listening on your feet and reacting. The preparation that goes into getting to the point where you can react that way is very cerebral.”

Burnham says that even now, jazz is not studied seriously enough as music. “There hasn’t been a whole lot of attention paid to the notes,” he says, noting that jazz often has been studied for anthropological reasons. As a result, jazz as an academic subject is taught in American studies programs as much as it is in music departments. (That’s true of the one jazz course at Princeton that Branker doesn’t teach: “Bebop — Triumph of the Avant Garde in Pop Culture,” which is in the American Studies department.)

Burnham points out that it’s not just race that makes it hard for the academy to come to grips with jazz. He argues that there also are real differences in the way each type of music is presented: “The way that the Western classical tradition is staged is as though it were some kind of timeless aesthetic force, whereas jazz is more fluid. It doesn’t stand still the way the score of a Beethoven symphony stands still. And so we have a hard time getting the tools we are most comfortable with in analyzing Western classical music to work on jazz music. We have tried-and-true ways of demonstrating the level of interest in Beethoven, but we don’t in some of these other types of music. But there are a few trailblazers who are working these things out” — including Branker, Burnham says.

Even now, the Concert Jazz Ensemble, unlike the University Orchestra and the Glee Club, does not have access to endowed funds. Burnham, who calls the ensemble “one of the most happening things going on,” hopes to change that. “It’s an extraordinary achievement on the part of Tony Branker, and now we desperately need to help him out. He’s created something that’s grown beyond his capability to do it all by himself.” In the fall, Burnham was busy trying to figure out how the jazz program could work with the new Center for African American Studies, perhaps by making a joint appointment or by designing an interdisciplinary jazz program “that would combine the practice of jazz with the study of jazz in a cultural context.”

No doubt, Branker could use the help. As he knows better than anyone, it’s fine to be a soloist but it’s even better when you’ve got some accompaniment.

No responses yet