The Battle of Princeton

An encounter in a farmer’s field 240 years ago changed the course of the Revolution

The following feature originally appeared in the Dec. 6, 1976, issue of PAW, in advance of the bicentennial of the Battle of Princeton.

New Year’s Day 1777 brought mild weather to Princeton, thawing out the frozen ground. In the afternoon the rains came on, and the roads turned into bogs of red mud. The yard in front of Nassau Hall was churned by the hooves of horses, the iron rims of fieldpieces, the feet of British soldiers. Regiment upon regiment had poured into the village during the previous 48 hours, and more still arrived, marching through heavy mire down the Post Road from New York and New Brunswick. By the end of the day some 10,000 British troops were assembled in and about the little college town: green-coated German jaegers armed with hunting rifles, the Black Watch regiment of Highlanders in kilts, blue-coated Hessian grenadiers with upswept moustaches, elite corps of light infantry and dragoons, and, above all, thousands of scarlet-coated foot soldiers. Well-trained and well-disciplined, they represented a third of the largest expeditionary force England had ever raised.

The first year of the American rebellion had not gone well for the British. After the opening skirmishes at Lexington and Concord in 1775, the Boston garrison had been besieged by an army of artisans and farmers twice its size and, suffering tremendous losses in its attempt to break out at Bunker Hill, had finally evacuated Boston in the spring of 1776. Yet, even as the patriots triumphantly occupied Boston, the Crown was gathering together a formidable army to repay their insolence. A few days before the colonies declared independence, this expeditionary force of 32,000 men, under the command of Sir William Howe, landed on Staten Island. A month later it began its campaign, soon demonstrating its vast superiority to the inexperienced American soldiers. Washington was dislodged from one defensive position after another on Long Island, on Manhattan, and in Westchester. His army shrank from about 25,000 to 4,000 men; his supplies were captured; his supporters lost faith. If Tom Paine called this period “the times that try men’s souls,” to a starving teenager in the American ranks it was more properly “the time that tried both soul and body.”

In November, Washington crossed the Hudson into New Jersey and appealed to its citizens to rise up against the British, but fright and disaffection were so great that, in a retreat of more than 100 miles, the Americans were joined by no more than 100 men. To make things worse, whole units of Washington’s already crippled army melted away as their enlistments expired. Civilians scrambled for safety. In Princeton the college was dismissed, and the students left to get home as best they could: many had to depart on foot, abandoning their trunks and other possessions. President Witherspoon saddled a mare for himself, put Mrs. Witherspoon in a two-wheeled gig, and together they headed for Pennsylvania. The Stocktons, after burying their silver in their garden at Morven, fled with their slaves. A third local signer of the Declaration of Independence, elderly John Hart of Hopewell, was forced to leave the bedside of his dying wife and take refuge in the woods.

By December 1, the British, having occupied New Brunswick, came to a halt, waiting for supplies and reinforcements. While they waited, the American army crossed the Delaware and secured its rear by confiscating or destroying every available boat. A relative of Jonathan Dickinson Sergeant 1762 wrote later that the scene at the Trenton ferry “called up the day of judgment, so many frightened people were assembled, with sick and wounded soldiers, all flying for their lives.” Charles Willson Peale described it as the “most hellish scene I ever beheld.” At the ferry Peale encountered a soldier, filthy and half-naked, wrapped in a blanket, his face full of sores; until the soldier spoke, Peale did not realize this was his own brother James.

Only a few hours after the last American soldier crossed the river at Trenton, the British occupied the town and began to scour the banks for boats. If they could get across the river, they could take Philadelphia within weeks, for the city was not even fortified. But there were no boats. Although there was lumber in plenty at Trenton, it did not occur to the British command that its soldiers might quickly build their own transports, and the river was declared impassible. On December 14, General Howe officially ended the campaign, returning to New York City and sending his men into winter quarters in a widely scattered string of garrisons across the two states.

From their side of the Delaware, the vulnerable Americans observed the enemy’s actions with mingled amazement and relief. Howe had held a mortgage on them, as a Virginia colonel wrote a friend back home, but he had not foreclosed it. Howe’s forbearance turned out to be a great mistake, yet a number of factors lent it some justification. First, he had no reason to apologize for a campaign which had already given the British total control over New Jersey and lower New York. Second, we can surmise that the British commander believed time to be on his side. He knew that on December 31 almost all the enlistments among the 3,000 surviving American troops would be up, leaving Washington with only a few hundred men. He also had just captured General Charles Lee, whom one of Howe’s aides called “the only rebel general whom we had cause to fear.” An eccentric former major in the English army who had joined the rebels as their second-ranking general, Lee commanded far more professional respect from the British officers than the fox-hunting Southerner Washington, who during his 16 months as commander-in-chief had not won a single engagement. Finally, Howe did not like to take risks with his troops: they were difficult to replace across miles of ocean, and each soldier represented a considerable investment by the British Treasury. (It was not much less expensive to manufacture disciplined soldiers out of the refuse of England’s slums and jails than it was to buy them readymade, like so many cattle, from German princes.) Howe presumably saw no advantage in taking a gamble. however slight, with these valuable troops now, when he was certain of having even better odds in a matter of weeks.

As the British army of occupation settled into quarters, some officers felt a little uneasy about the distances separating the New Jersey garrisons — the troops in Trenton were nearer to Washington’s encampment across the river than to their own comrades in Princeton and Bordentown — but almost no one could believe that the rabble surrounding Washington represented a serious threat. A Hessian officer in Trenton summed up the prevailing mood in a diary entry on Christmas Day 1776: “That men who ... have neither coat, shoe nor stocking, nor scarce anything else to cover their bodies, and who for a long time past have not received one farthing of pay, should dare to attack regular troops in the open country, which they could not withstand when they were posted amongst rocks and in the strongest entrenchments, is not to be supposed.”

For this lack of imagination the Hessians paid dearly. Washington, desperate to use his troops to some advantage before their enlistments ran out, made his famous crossing of the icy Delaware and, in a swirling snowstorm on the morning of December 26, surprised and captured the Trenton garrison. His first victory was an unqualified success. While inflicting more than 100 casualties and capturing nearly 900 prisoners, the Americans lost only two men of their own, both frozen to death during the march back to the ferries with the Hessian prisoners.

As the British army of occupation settled into quarters, some officers felt a little uneasy about the distances separating the New Jersey garrisons — the troops in Trenton were nearer to Washington’s encampment across the river than to their own comrades in Princeton and Bordentown — but almost no one could believe that the rabble surrounding Washington represented a serious threat.

In New York City, General Howe could scarcely believe the news. Not only had the Trenton garrison surrendered, but the Hessian garrison at Bordentown had fled its post, leaving the whole eastern bank of the Delaware open to the Americans. Then came more bad news: seeing the British posts abandoned, Washington had made a second crossing into New Jersey and the entire strip along the river was in his hands. With a great deal of inadvertent help from the alarmed enemy troops, he had managed to convert an isolated raid into a significant advance on the British front.

Washington could not follow up any further on his success, however, unless he could persuade his men to reenlist. On December 31, he ordered the regiments to be paraded. These were his best troops — not short-term militia, but trained regulars who had fought beside each other for a year. “In a most affectionate manner,” according to a sergeant present, the General “entreated us to stay.” He alluded to the victory at Trenton, appealed to their patriotism, begged them to remain one month more. “The drums beat for volunteers,” recalled the sergeant, “but not a man turned out.” They had done their duty, and they wanted to go home.

Washington wheeled his horse about, rode in front of the regiment, and addressed them again. “My brave fellows,” he said, “you have done all I ever asked you to do, and more than could be expected: but your country is at stake.” A few days earlier the General had ordered Tom Paine’s small pamphlet read aloud to his men, and its words had warmed them on the cold march to victory at Trenton. Echoing its tide, Washington now declared, “The present is emphatically the crisis, which is to decide our destiny.” The drums beat a second time. The soldiers, half-starved and halffrozen, looked mutely at one another. Finally one said, “I will remain if you will.” Another responded, “We cannot go home under such circumstances.” One by one, those still fit for duty stepped forward.

Not every soldier volunteered under the impulse of patriotism, Washington, pledging his personal fortune, promised $10 to each man who would stay six weeks. Lesser officers, such as Major John Polhemus of Hopewell, did the same. Facing the prospect of finding their way home on foot in the dead of winter, without adequate clothing and without a penny to pay for lodgings or food en route, about half of the American soldiers elected to stay on and collect the promised bounty.

While Washington was settling enlistments ln Trenton, the British were responding to the threat he posed by congregating at Princeton 12 miles to the north. This small village of 60-80 houses had been under British occupation since early December. The garrison there had occupied both public buildings and private homes, making themselves thoroughly unpopular in the process, for they did not distinguish among property belonging to the town’s patriots, its loyalists, or its pacifist Quakers. Fences were burned, crops and livestock taken, horses and wagons confiscated, blankets and household supplies pilfered, regardless of the owner’s political sentiments. The troops built a fireplace in the Presbyterian Church and burned the pews; horses were stabled in Nassau Hall; the Stocktons’ library was burned and their wall portraits slashed by bayonets; and Jonathan Dickinson Sergeant’s new house burned down — perhaps through carelessness, perhaps not.

Besides property damage, the local residents had suffered the humiliations of a conquered people. Even though those who remained to greet the advancing British army were for the most part favorably disposed toward the King, they were treated with insolence. Sober Quakers, refusing to uncover to the soldiers, had their hats tweaked down over their noses. Honest farmers were taunted by the armed intruders and dared not reply. Moreover, according to one Princeton resident, not a few women were raped. To compound the general misery, men could not trust their neighbors: a number became secret informers, pointing out to the British here a family that might he safeguarding the property of an absent rebel, there a family with a relative who had joined the militia.

Thus it was an already desolate and terrorized town that now received thousands of additional troops. They sought shelter in barns, sheds, and outbuildings; many — even officers — had to sleep wrapped in their cloaks on the frozen ground. The pace of destruction quickened: to defend themselves from the cold in an open countryside with little timber, the soldiers turned to burning fences, straw, carriages, wall moldings, anything flammable. Supplies of flax were taken for use in making fortifications, and leather was robbed from the town’s tanneries.

Before the British troops could do further damage, how ever, Howe sent General Lord Cornwallis to take charge. He arrived late at night on New Year’s Day after a punishing 50-mile horseback ride from New York and immediately called a candlelit council of war at Morven. Upon hearing the officers’ reports, he ordered the troops to move out before dawn and march on Trenton. He was hoping to force Washington into a full-scale battle, pitting the might of the British army against the feeble handful of rebels. No one could doubt the result of such a battle: the American army would be destroyed and the rebellion forever quashed.

Meanwhile, on that same rainy New Year’s Night, Benjamin Rush 1760 was leaving General Washington’s headquarters and mounting a fast horse. He had urgent orders to deliver. Between re-enlisted regulars and short term militia, Washington had only 3,335 troops under his command in Trenton, but some miles away near the Delaware River was a large, hastily assembled group of Pennsylvania volunteers who had answered his call to arms. Washington wanted them to move up and join him, thereby consolidating all the American forces. Riding through the dark and rain, Rush found the Pennsylvania commanders, and shortly after midnight the militia set off on a long march, stumbling and cursing through mud that came up to their knees. They arrived at Trenton well after daylight, bringing Washington’s troops up to about 6,800 men.

Sniping from behind trees, destroying bridges, felling trees as roadblocks, the riflemen were so successful at buying time for Washington that it was dusk when Cornwallis’s advance guard finally reached Trenton.

Numerically, the American army was now closer to the British army in strength, but Washington realized that almost all his men were simply that: men, not soldiers. With the exception of the 1,400-1,500 re-enlisted regulars, his forces consisted of nothing but tradespeople and farmers who had never fought a battle in their lives, and Washington knew well that such raw recruits could not be trusted in open battle against the British. When he had sent such troops toward British lines — at Long Island, at Kip’s Bay, at White Plains — they had panicked and fled. A frontal assault against the British soldiers now advancing on Trenton was therefore out of the question. Instead, Washington posted his militia in a defensive position on a hill behind the Assunpink Creek, overlooking the bridge to Trenton. Then he sent a detachment of Continental riflemen up the TrentonPrinceton road to harass the British advance.

Sniping from behind trees, destroying bridges, felling trees as roadblocks, the riflemen were so successful at buying time for Washington that it was dusk when Cornwallis’s advance guard finally reached Trenton. While Washington and his army watched from the hillside, the American marksmen dashed from house to house in the town, still contesting the British advance. After the riflemen retreated across the Assunpink bridge, Washington ordered his artillery to open up on their pursuers. Three times the British charged the bridge and were repulsed by the cannonade. The third time, the Americans let the British come nearer, then raked them with cannisters of grapeshot. “Such destruction it made, you cannot conceive,” an American artilleryman wrote later. “The bridge looked red as blood, with their killed and wounded and their red coats.”

Since night was falling, Cornwallis decided to postpone further attack until daybreak. Like his superior Howe, he was reluctant to risk troops unnecessarily. “We’ve got the old fox safe now,” Cornwallis is reported to have said. “We’ll go over and bag him in the morning.” A glance at the map explains Cornwallis’s confidence: New Jersey is simply a large peninsula and, with the British line of march once again extending from New York to Trenton, the Americans were trapped in that peninsula. They could not escape by land without giving Cornwallis the battle he sought; they could not escape by water, for there were not enough boats to carry off the entire army during the night. With their lines of retreat closed, it seemed that the Americans had to accept the battle Cornwallis was forcing upon them.

Over the creek in the American camp, the soldiers understood their dilemma, yet it did not depress their spirits, perhaps because so few of them had ever been in battle before. A young Rhode Island veteran, Stephen Olney, was deeply troubled by their “most desperate situation,” but he could not get his comrades to share his mood. When he asked a fellow lieutenant what he thought now of their chances for independence, the officer shrugged off Olney’s concern, answering cheerfully, “I don’t know; the Lord must help us.” Instead of worrying, most of the men went immediately to sleep, especially the exhausted militiamen who had been marching all the previous night.

At this critical moment, with the fate of the American army hanging in balance, a small miracle did occur. While the men slept, a cold north wind came up, the temperature dropped, and the roads froze over, the snow and ice and mud forming a surface as hard as pavement. The change in weather was a providential gift to the American cause, enabling its commander to see a way out of the British trap. He would take advantage of the cover of darkness and the good state of the roads to march on a wide sweep north roughly parallel to Cornwallis’s army, put himself in Cornwallis’s rear, and attack the small British garrison left at Princeton. If he succeeded, it would put his force north of the enemy line of march, safely extricated from the New Jersey cul-de-sac.

A few hours earlier this scheme would have been patently impossible: daybreak on January 3 would have found the Americans bogged down in mud miles below Princeton, giving Cornwallis ample time either to turn about and fall upon their flank or to hasten up to Princeton on the short, direct road which he controlled and, arriving first, smash the Americans in open battle. But the mobility afforded by the frozen roads gave Washington hope that he might have just enough time to reach Princeton, attack, and move on out of reach before Cornwallis woke up to his disappearance at dawn.

Though it was an exceedingly dangerous plan that aimed the American army directly into the heart of enemy-occupied territory — where it could be sandwiched between the British army at Trenton and the even larger British force in New York City — Washington hoped to slip quickly between these pincers before he could be caught. In truth, he had few alternatives. He did not want a general battle, which promised certain defeat. Neither did he want to fall back across the Delaware, even if that were practicable, since a retreat could snuff out the flickering hopes rekindled at the Battle of Trenton. The march on Princeton might be a disaster, but “One thing I was sure of,” Washington reported to Congress, “that it would avoid the appearance of a retreat.”

The night was calm, but intensely cold, and so dark that the marching line of men could scarcely distinguish obstacles. With no idea where they were going, the men stumbled through heavy woods, across an icy stream, over difficult terrain covered with stunted growth, a stretch of swampland, another stream. Many had no shoes; the ground was literally marked with the blood of their feet.

Shortly after Washington and his general officers committed themselves to this plan, orders were whispered through the ranks. Sleepy men stumbled to their feet, groped for weapons, were cautioned to silence. The wheels of artillery carriages were muffled with rags. Officers tried to herd the men into formation and move them off in small detachments, but there was much confusion. “No one knew what the Gen. meant to do,” recalled one captain. Regimental commanders, as unaware of the overall plan as their men, misunderstood orders passed along in nearly inaudible voices. It was three hours before most of the troops were underway.

A detachment of 400 New Jersey militia was left behind to keep the campfires going and to deceive British pickets into believing the army was digging entrenchments against the next day’s attack. So great was the emphasis on secrecy that none of these men knew where their comrades had gone: their orders were simply to withdraw at daybreak and follow the army’s tracks. If they could not follow, they could return to their homes in nearby counties. Washington was taking no chance that any soldier captured by the British that night would be able to reveal his plans to the enemy.

The night was calm, but intensely cold, and so dark that the marching line of men could scarcely distinguish obstacles. With no idea where they were going, the men stumbled through heavy woods, across an icy stream, over difficult terrain covered with stunted growth, a stretch of swampland, another stream. Many had no shoes; the ground was literally marked with the blood of their feet. During halts, swaying men fell asleep standing up, their arms supported by their comrades’ shoulders. When the army reached the Quaker Road, the march became easier, but dawn on January 3 found them at the bridge over the Stony Brook, about three miles short of their objective.

Here Washington paused to arrange his troops in columns for the attack on Princeton, basing his dispositions on the intelligence reports he had received over the past few days, which assured him that the back side of town was entirely unprotected. On December 30, a mounted scouting party, led by Colonel Joseph Reed 1756, had learned that the roads south of the college were virtually unpatrolled. A day later Washington had actually received a map, prepared by an “intelligent young gentleman” who had just slipped out of Princeton, showing that the British had, in fact, prepared defenses only for an attack along the main highways leading directly into town. Furthermore, this map showed the existence of a disused track, the Saw Mill Road, which branched off the Quaker Road and led through those undefended fields behind the college.

Washington’s exact orders are not known, but the most plausible hypothesis is that he intended to send most of his troops, under General John Sullivan, on the Saw Mill Road to attack the town from the rear, while General Nathaniel Greene led the remainder up to the Post Road to enter the town from the southwest. According to this theory, Greene’s force would attack first and, as the surprised British garrison gathered to repel him, Sullivan would throw his men in on its unprotected flank. Naturally Washington hoped to catch the British napping, just as he had the Hessians at Trenton.

Unfortunately for Washington’s plans, however, not only were the three crack British regiments in Princeton wide awake, but they were actually under arms. In the night Cornwallis had sent orders directing the 17th and 55th regiments to escort supplies to him at Trenton, while the 40th regiment remained in quarters at the college to hold the town. Even as Greene’s and Sullivan’s columns separated, the British were marching down the Post Road, and the result was a moment of sudden surprise for everyone when the two forces spotted each other.

From the van of the British party Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Mawhood quickly decided to split his command, sending most of the 55th regiment back to town with the supply wagons while he led the 17th regiment in an attack on this unexpected group of rebels. Mawhood probably assumed he was confronting a small militia detachment — after all, Cornwallis was supposed to have the American army pinned down in Trenton — and he must have been confident that the 276 men he was keeping under his command could easily handle the situation. Within seconds the 17th regiment had left the Post Road and was racing to intercept Greene’s front guard before they could capture the nearest high ground.

Both forces met on a hill covered with the orchard, house, and barns of a Quaker farmer named William Clark. Kneeling behind a fence, Mawhood’s men opened fire first but their bullets went high, cutting limbs from trees in the orchard to drop in a harmless shower on the Americans’ heads. These Americans — Greene’s front guard — were regulars, some 350 men under the command of General Hugh Mercer. Not yet in formation, they wheeled about to face Mawhood’s position, taking perhaps their first casualty in the process: a corporal who, seeming to bend forward to receive the enemy’s ball, fell dead on the spot.

Supported by two artillery pieces, Mercer’s men formed and advanced. So did the British. “The sun shone upon them and their arms glistened very bright,” noted Sergeant Joseph White of Massachusetts, “it seemed to strike an awe upon us.” Then both sides fired at once, and the smoke from the discharge of the two lines, mingling as it rose, “went up in one beautiful cloud.” The American artillery reloaded with cannister shot, which flew through the air with “a terrible squeaking noise.” Firing their rifles and muskets, both armies kept on marching toward one another.

An 85-year-old farmer in a neighboring house watched the battle start from his doorstep, but he did not stay to see the finish. ‘‘The guns went of [sic] so quick and many together ... ” he reported, “we presently went down into the Cellar to keep out of the way of the Shot.” In the Clark farm house itself, Mrs. Clark lay recovering from a miscarriage, too weak to struggle to her feet. But when shot began coming through her window, her husband and her nurse managed to carry her down to the cellar, bed and all.

The American fire was the most destructive and Mercer’s force seemed to be on the verge of victory when the 11th regiment rose to its feet and charged the rebels with fixed bayonets. Unable to reload before the British were upon them and themselves unequipped with bayonets, the Americans went down before the British onslaught. In distress, General Mercer called “Retreat!” Another moment and he fell on the icy snow as the British slashed at him repeatedly. A wounded 18-year-old lieutenant from Virginia, begging for quarter, was shot deliberately through the chest and stabbed in 13 places. It was savage man-to-man combat, with bayonets against empty rifles and bare hands.

Mawhood’s men seized the American cannon and turned them on the remnants of Mercer’s brigade, now fleeing for their lives. At this point, however, the rest of General Greene’s force came up. This reinforcement consisted of several hundred Pennsylvania militiamen, part of the same group that had had only a few hours sleep in the last 48 hours, accompanied by a battery of cannon manned by 82 boys recruited from the Philadelphia waterfront by Captain Joseph Moulder. The militia, who had never seen a battlefield before, looked with anguish at the blood on the ground and the mangled bodies of the dead and — just as militia had always done in this campaign under similar circumstances — broke away from their officers and ran for safety.

Washington galloped into the battle. Taking in the situation at a glance, he rode toward the British line, trying to rally the terrified militia. “Parade with us, my brave fellows!” he cried out.

Nonetheless, the Philadelphia battery stood firm and, for a few crucial moments, offered the only resistance to the charging ranks of English soldiers. When one piece of grapeshot grazed his elbow tearing his coat, another carried away the inside edge of his sole, and a third nicked his hat, a Delaware volunteer trying to support the gunners was forced to withdraw. Yet Moulder’s young artillerymen, all under the age of 23, held the 17th regiment in check until help could arrive.

During the engagement in Clark’s orchard, most of the American army had halted on the Saw Mill Road. At first they had not paid much attention to the sounds of musketry and cannon, but as the firing continued Washington realized that Greene’s men were engaged in something more than a mere skirmish. Ordering two brigades of regulars to follow him — Hitchcock’s 253 New Englanders and Hand’s 200 Pennsylvania riflemen — Washington galloped into the battle. Taking in the situation at a glance, he rode toward the British line, trying to rally the terrified militia. “Parade with us, my brave fellows!” he cried out, as he rode between the American and British lines, exposing himself to fire from both sides. “There is but a handful of the enemy and we will have them directly!”

Many of the militia, enheartened by Washington’s example, did rally. Others, running into Hitchcock’s and Hand’s brigades, were dragged forcibly into formation by swearing officers. Once again the Americans advanced on the 17th regiment, which fired off musketry and field pieces loaded with grapeshot. To Stephen Olney it was “the most horrible music about our ears I had ever heard,” but again the English had aimed too high and the shot whistled harmlessly overhead. When the smoke cleared away, the Americans were still advancing and at their head General Washington rode calmly, waving the troops on.

The 17th regiment, after turning back two successive waves of Americans, could hold no longer. It had taken heavy casualties and lost most of its officers. Now Mawhood ordered the withdrawal. One last bayonet charge and the survivors of the 17th broke through the American line and fled down the Past Road away from Princeton. Intoxicated by the sight of redcoats in retreat, Washington himself led the pursuit, hallooing exuberantly, “It’s a fine fox chase, my boys!” as he galloped out of sight. So excited was he that many minutes passed before he recalled his duty as commander and turned about to rejoin his men.

Clark’s quiet orchard and wheat field, left in possession of the Americans, had been transformed within 45 minutes into a charnelhouse. More than 100 casualties, most of them British, lay “scattered about, groaning, dying and dead.” According to an eyewitness, “One officer who was shot from his horse, lay in a hollow place in the ground, rolling and writhing in his own blood, unconscious of anything around him. The ground was frozen, and all the blood which was shed remained on the surface, which added to the horror of this scene of carnage.” The survivors began the grim business of carrying the wounded into the farmhouses to be cared for by the local women and hauling the dead on sleds to mass graves and “heaping them in.”

Despite the horror, the soldiers rejoiced in their victory. The old farmer, welcoming them to his house, said some were “laughing out right, others smileing [sic], and not a man among them but showed Joy in his Countenance. It Really Animated my old blood with Love to those men that but a few minutes before had been Couragiously [sic] looking Death in the face....”

The Battle of Princeton was over for these soldiers, but not for the men attached to Sullivan’s column who had been halted all the while on the back road into town. From this position they had been keeping a wary eye on the 55th regiment as it moved back under orders toward the college, while the 55th regiment kept a no less cautious eye on them. Not knowing the other’s precise strength, neither force had taken action at all. Now, with the 17th regiment’s defeat, the 55th regiment moved into position to defend the town, while the 40th regiment marched out from the college to join it.

Led by Mawhood, who had escaped during the retreat, the 55th and 40th regiments made their stand on the edge of Frog Hollow (near today’s Princeton Inn College), it was a good position, but the British troops seemed to be shocked by the realization that they were confronting the entire American army and demoralized by the 17th regiment’s defeat. When Sullivan’s force began its attack, the British put up little resistance. Those who did not surrender within minutes were chased into town, where some took refuge within the strong stone walls of Nassau Hall, knocked out the windows with the butts of their rifles, and prepared to make a last-ditch stand.

Before the soldiers in Nassau Hall could organize, however, the Americans enveloped the building. While young Alexander Hamilton’s battery fired off round shot — one of which is supposed to have decapitated the portrait of King George II in the prayer hall — New Jersey militia, under the command of Princeton resident James Moore, broke in a door and charged into the building. A white flag appeared, and the British — “a haughty, crabbed set of men,” in the view of one American sergeant — surrendered.

The Battle of Princeton ended with this short cannonade. Killing 100 men and wounding or capturing 300 more, the Americans had virtually destroyed three of England’s finest regiments. Although they lost many irreplaceable officers, especially the greatly lamented Mercer, who died after nine pain-filled days, the Americans seem to have taken less than half as many casualties as the British. They also captured, obviously, a wagon train of supplies —a fact Washington did not choose to emphasize in his report to Congress lest that body use it as an excuse for not providing his soldiers with much-needed equipment.

After the battle, the triumphant but tired Americans fell to exploring the town, which they thought a pretty little place, despite the ravages of the enemy. Princeton’s elegant brick buildings, especially the college, were duly admired, but the roaming soldiers were mainly interested in what the town could offer in the way of plunder. A fortunate few sat down to the breakfast that the 40th regiment had been about to enjoy an hour before. Others walked off with silver coins, a pair of silk shoes, hard spirits, a gilt Bible, and other small articles of value. Some believed that Princeton was a Tory village; in any case, the looting American soldiers apparently were no nicer in selecting their victims than the British had been.

By about 10 a.m., shots from the direction of Stony Brook, where a work party was tearing up the bridge, alerted the soldiers in town that Cornwallis, having woken up to Washington’s ruse, was coming up on their rear. The Americans had time to finish swapping their lice-ridden blankets for British issue before they got orders to pull out. The militia straggled as always, but the whole army was away by 11 a.m.

After the battle, the triumphant but tired Americans fell to exploring the town, which they thought a pretty little place, despite the ravages of the enemy.

After a cautious reconnaissance, Cornwallis’s army entered Princeton before noon “in a most infernal sweat — running, puffing, and blowing, and swearing at being so outwitted.” They looted the town yet again, unleashing their infuriation on the hapless citizens, three of whom they arrested and forced to march along with them. “Princeton is, indeed, a deserted village,” wrote Benjamin Rush when he saw it four days later; “you would think it had been desolated with the plague and an earthquake, as well as with the calamities of war.”

Even so, the college town could be grateful at least that the British did not tarry. Having lost his chance to annihilate the rebel army, Cornwallis was now in a quake lest Washington reach New Brunswick, where a small handful of British soldiers were guarding not only an enormously valuable quantity of stores and supplies but also a war chest of silver and gold worth about £70,000. Indeed, Washington would have liked to attack New Brunswick, but his men were reaching the limits of their endurance. Many had not eaten for more than a day, and others had slept only a couple of hours in nearly three days. Moreover, encumbered with the prisoners, wagons, and supplies captured in Princeton, the American army for once could not be expected to outmarch its pursuers. Reluctantly, Washington turned north at Kingston and began a retreat, executed in stages over the next few days, to the safety of the Watchung Mountains around Morristown.

Too worried about his supplies to follow Washington, Cornwallis drove his men all night to reach New Brunswick. There they got little rest, for they were routed out hours before dawn each morning to stand guard: Cornwallis, having learned the hard way about his opponent’s penchant for dawn attacks, was taking no chances.

But the damage was done. Although the American soldiers would never capture the British supplies, they had already captured something far more important: the imagination of their countrymen. As the news of the Battle of Princeton spread through the former colonies, it brought new hope and new adherents to the American cause. Only three days after the victory a visitor in Virginia was writing that “the minds of the people are much altered. Their late successes have turned the scale and now they are liberty mad again.” In New Jersey — that state which a month earlier had supinely awaited British occupation, to Washington’s outrage and disgust — men flocked to join the militia and small units wandered the countryside hunting down loyalists and King’s soldiers in “a sort of continual hunting party.”

Within a month the British had to contract their forces in New Jersey until they occupied only New Brunswick and Perth Amboy. Even those garrisons were so harassed that it became unsafe for small foraging parties to venture far in search of food or firewood. As a result, the large British army in New York, which had expected to feast on the stores of New Jersey’s granaries, lived out the winter on “salt and ship provisions.” By summer New Jersey was entirely back in American hands.

Officially, the British treated the Battle of Princeton as a minor affair. In fact, the New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, the chief loyalist organ, presented it at first as a victory for the 17th regiment. After all, the 276 men of the 17th had stood off successive attacks by more than 1,500 rebels and, when surrounded, had still managed to break through the American lines and effect a reasonably orderly withdrawal. On future recruiting posters the 17th regiment would bill itself, with ample cause, as “the Heroes of Prince Town.”

Nonetheless, the American side was not without its heroes — the gallant General Mercer, the steady men of Hitchcock’s and Hand’s brigades, the brave youngsters in Moulder’s battery —and it had needed those heroes much more than the British needed theirs. Even the Pennsylvania militia came in for a large share of adulation: for the American public the important point was not that their soldiers had run away, but that for once they had rallied and fought again. The news that the armed yeomanry had put professional soldiers to flight dispelled the widespread belief in the invincibility of the British army, a change of heart which Philip Freneau 1771 expressed in these lines:

When first Britannia sent her hostile crew

To these far shores, to ravage and subdue,

We thought them gods, and almost seemed to say

No ball could pierce them, and no dagger slay —

Heavens! what a blunder—half our fears were vain;

These hostile gods at length have quit the plain ...

Furthermore, the Battle of Princeton made a hero of Washington, establishing the public’s confidence in him both as a brilliant tactician and as a fearless leader in the field. His reputation rose to a height that, to the immense benefit of the nation over the coming years, virtually ensured that he would remain as commander-in-chief.

For their part, the British never again felt inclined to underestimate the rebel general. Whatever their official attitude, in private they bitterly acknowledged that by his clever ruse he had saved his army and won through to a strong strategic position in the mountains of northern New Jersey from which he could swoop down and strike at will at the British outposts. One of Howe’s aides wrote regretfully in February that Washington “persists in his tactics of continuous alarms, which make our men very uncomfortable. We shall be considerably weaker in the next campaign.’’

In truth, the position of the two armies was not so much reversed that the British did not manage to hold on for six more years, keeping the Americans on the defensive much of the time. Victory at Princeton did not give Washington’s army enough men, enough weapons, enough training, enough clothing, enough food, enough money to win the war. What it did give them, in Thomas Paine’s words, was the “spirit of conquerors,” the kind of spirit that made it impossible for the Americans ever again to come so perilously close to losing their war.

The 26 Days’ Tyranny: What Happened to Princeton’s Patriots, Tories, and Quakers During the British Occupation

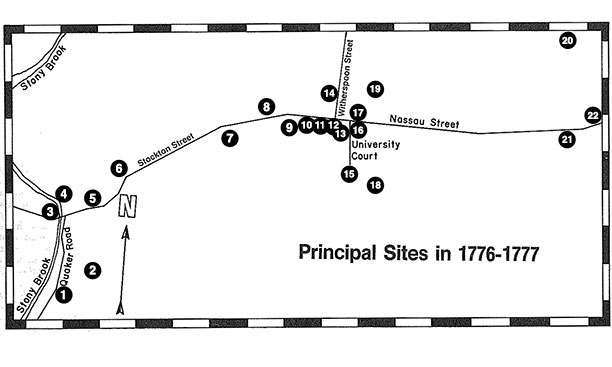

1. Quaker Meeting House. Near the Stony Brook clustered a group of Quaker families, descendants of original settlers who arrived there around 1696. Opposed to the war on religious grounds, they trusted that the occupying army would respect their neutrality. Instead, the British quartered troops in their Meeting House and pillaged their farms and homes. Joseph Olden, for example, lost a mare, five hogs, a ton of hay, fence rails, a side of beef, and a beaver hat, among other items. After the Americans recaptured Princeton, these same Quakers found themselves objects of suspicion, and many stood in danger of losing all they owned because their faith prohibited them from swearing a required oath of allegiance to the cause of independence. At this point, however, several influential townsmen came to their rescue, pledging their own fortunes as a bond for the good conduct of their Quaker neighbors.

2. Thomas Clark house. Following the battle, soldiers carried the wounded Mercer to this Quaker farmhouse to be nursed by Miss Sarah Clark and her black maidservant. That afternoon British soldiers are said to have invaded the sick room, ripped the cravat from the general’s neck, and insulted him as he lay unable to resist. He died there on January 12.

3. Worth’s Mills. During the battle an errant cannonball, probably from an American fieldpiece, entered a house near the mills and hit a woman, severing her leg at the ankle. Though the mills apparently were not damaged, American troops destroyed the nearby bridge to impede Cornwallis’s advance.

4. Johnson, Millette, and Stockton farms. In this vicinity, north of the Post Road, lived a number of prominent families. John Johnson, a large landowner, church elder, and distiller, favored the Revolutionary cause, but when American press gangs came for his horses and wagon in early December, he did not hesitate to hide them in the woods. As a result, with the help of Princeton student Joseph Clark, he was able to get some of his own goods away before the British arrived — fortunately for him, since the enemy did plunder his property. One of Johnson’s neighbors, a French-Canadian and Tory named William Millette, returned to Canada to wait out the war, but he and his wife seem to have missed Princeton. They sent £10 to help repair the Presbyterian Church, damaged by the British, and moved back after the war. A third neighbor was Princeton’s most notable Tory, Joseph Stockton. A cousin of Richard Stockton 1748, the signer of the Declaration of Independence, Joseph joined a Loyalist regiment in August 1776. He escorted Colonel Mawhood to New Brunswick after his defeat at Princeton and was killed a few months later while guiding a foraging party. Joseph’s brother Richard Witham “Double Dick” Stockton also fought in the Loyalist cause.

5. Blacksmith’s home. This may be the site of the forge owned by a 59-year-old Quaker blacksmith who had the misfortune to run afoul of some of Cornwallis’s thwarted soldiers on January 3. They stole his shoes, marched him in his stocking feet to New Brunswick, and held him for a day and a night before allowing him to come limping home.

6. Constitution Hill. So-called because tradition says the Constitution of New Jersey was drafted there in the summer of 1776, this was the site of the house that served as Washington’s headquarters when the Americans were in retreat. It was the home of Major Robert Stockton, quartermaster in the American army and a cousin of Richard Stockton of Morven and Joseph Stockton the Tory. British soldiers did £655 damage to Robert’s house and farm, and looted his tannery business in town.

7. The Barracks. Reputedly the oldest building in Princeton, this early Stockton farmhouse probably housed troops during the French and Indian War as well as during the Revolution.

8. Morven. When he signed the Declaration of Independence, Princeton’s most eminent lawyer and landowner, Richard Stockton 1748, pledged his life, his fortune, and his sacred honor. Within months. all three were in jeopardy. As the British advanced through New Jersey, the Stocktons made hasty preparations to leave Morven, where they had lived graciously in the manner of English squires. They were burying valuables in the garden when Annis Boudinot Stockton remembered that Whig Society members had left behind paper which would hang them all. She brought the documents to Morven and hid them, thereby earning the first feminine membership in the Whig Society. Leaving their property in the care of their 12-year-old son, the Stocktons fled to relatives in Monmouth County. There Richard was betrayed by local Tories, arrested, and according to his son in-law Benjamin Rush subjected to the most brutal and inhumane treatment. While in captivity, his health failed and, apparently to gain better treatment, he signed a pledge to “remain in peaceful obedience to his Majesty.” When released in 1777, he returned to find the British had left Morven in ruins. (Rush estimated his losses at £5,000.) Once renowned for his affability, Stockton withdrew from public life and died at the age of 51.

9. Home of Jonathan Dickinson Sergeant 1762. On the site of today’s Nassau Club. Sergeant built a house for his bride Margaret Spencer in 1775. He was a lawyer, an officer in the Provincial Congress, and a member of the Continental Congress, whose sessions he was attending when the British advances on Princeton in December 1776. Sergeant’s young wife delayed leaving their home until finally her husband’s Tory classmate, Dr. Absalom Bainbridge 1762, took her firmly in hand and sent her off with her baby and sister to safety in Pennsylvania. In their absence, the house burned down and, rather than rebuild it, the family chose to settle in Philadelphia.

10. Home of Jonathan Deare. Another lawyer and active patriot, Deare served in both the Provincial Congress and the militia. During the occupation he lost 50 grafted trees from his orchard as well as furniture and household supplies. Despite his losses, he stood surety for some of Princeton’s Quakers the next fall. Deare’s house, moved from the site later occupied by Commons to Bayard Lane, is now the Peacock Inn.

11. Presbyterian Church. A two-story brick structure with 57 pews, the Church was the spiritual home for many of the town’s leading patriots, including Robert and Richard Stockton, Richard Longstreet, Enos Kelsey, James Moore, William Scudder, John Johnson, and, of course, its pastor, the Rev. John Witherspoon. When Cornwallis’s troops were quartered here, they stripped the interior, inflicting £160 damage. The Church remained a hollow shell until after the war.

12. President’s House. The commander of the occupation troops, General Leslie, used today’s Maclean House as his headquarters, but on January 3 it was occupied by officers of the 40th regiment, who were preparing for breakfast when they were called away by sounds of gunfire. Their breakfast was eaten with great relish an hour later by victorious American officers. Nearly opposite was the store of merchant Enos Kelsey 1760, a member of the Provincial Congress who, as a major in the militia, was one of the few New Jerseyites to come to Washington’s aid in the black days of November 1776.

13. Nassau Hall. In addition to serving as quarters for troops (and as a stable for their horses), Nassau Hall was a hospital and a prison for about 30 local Whigs during the occupation. While the British did not treat the college gently, the Americans damaged it even more when they reoccupied it.

14. Road to Tusculum. Today’s Witherspoon Street leads to Tusculum, a farm owned by John Witherspoon. Although occupied by British troops, his home suffered less than that of his fellow signer, Richard Stockton. The college’s president lost sheep and cattle, but only a few household items, and he evidently never bothered to file a claim for damages.

15. Prospect Farm. Jonathan Baldwin 1755, the owner of Prospect Farm, was also steward of the college and, if undergraduate complaints are to be believed, he was responsible for some of the worst meals ever served up at Old Nassau. He married Sally Sergeant, a daughter of Jonathan Sergeant and halfsister of Jonathan Dickinson Sergeant. Baldwin served in the Provincial Congress and in 1778 was put in charge of distributing balls and cartridges to the army, in which connection he was accused — apparently falsely — of profiteering.

16. Hudibras Tavern. Situated halfway between New York and Philadelphia on the main stage road, Princeton was early known for its inns. The most prominent in Revolutionary annals was the Hudibras, owned by Colonel Jacob Hyer, who kept a horse in his barn for the use of express riders carrying messages between the Continental Congress and General Washington. Hyer fought at the Battle of Princeton at the head of his militia unit, whose ranks included his older son, a veteran of the siege of Boston and the Canadian campaign of 1776. Although the British drank up Hyer’s wines, whiskey, and gin without payment, and stole or damaged his tableware and 11 of his featherbeds, he was open for business again on January 9, hosting a meeting of the Committee of Safety. The tavern proprietor posted bond for several of his Quaker neighbors when they refused to swear allegiance to the American cause.

17. Bainbridge House. Dr. Absalom Bainbridge 1762 rented this Georgian house from Robert Stockton around 1774. A Loyalist, Bainbridge was married to a daughter of Sheriff John Taylor, whom Howe selected as His Majesty’s High Commissioner of New Jersey, and their home served as Howe’s headquarters in early December 1776. After the Americans recaptured Princeton, Bainbridge moved to New York behind British lines rather than take the oath of abjuration and allegiance. His political sentiments, however, were not stronger than his humanitarian instincts. Not only was he largely responsible for Margaret Sergeant’s safe escape from Princeton, he later was able to get Major John Polhemus of Hopewell paroled from British prison. The doctor died in New York, but some of his family returned to Princeton and one of his grandsons, John Maclean, became the college’s 10th president. Bainbridge’s home now houses the Historical Society of Princeton; its former garden is the site of the Garden Theater.

18. Farm of Jonathan Sergeant. Treasurer of the college, Sergeant bought this farm from his son-in-law Jonathan Baldwin 1755 and died there of smallpox during the British occupation. The farm, which was pillaged by the enemy, included the land on which Palmer Stadium now stands.

19. Moore’s Tannery. James Moore, the militia captain who led the charge on Nassau Hall, had a personal grievance against the British: they had looted over £600 worth of hides from his tannery. Moore Street is named after him.

20. Farm of Richard Longstreet. The year 1776 brought much tragedy to the Longstreet family and their connections. In October, their relation by marriage, Philip Vickers Fithian 1772, died of camp fever while serving as a chaplain in the Continental army. In November, Longstreet’s son-in-law Dr. John Beatty and his brother Reading Beatty, both Continental soldiers, were captured by the enemy. In December, Longstreet’s other son-in-law, Lemuel Scudder, had his mills destroyed by the British. In early January, Hessian jaegers are believed to have been quartered in Longstreet’s house. The farmer’s two sons joined the militia, but he himself seems not to have held any Revolutionary office.

21. Castle Howard. Although a retired British officer, Captain William Howard was a good patriot who painted on his mantelpiece “No Tory Talk Here” as a warning to his ardently Loyal wife. But as soon as Sarah Howard’s gouty husband died in 1776, she married Lieutenant Ibbetson Hamer, an English soldier who shared her views, and she frequently entertained his fellow officers during the occupation. As a result, she and her new husband had to leave Princeton; their property was confiscated and eventually sold to John Witherspoon.

22. To Scudder’s Mills. Major William Scudder owned fulling and grist mills at the juncture of the Stony Brook and the Millstone River (now under Lake Carnegie). British troops were quartered there, and Scudder’s house and mills were burned on December 31. (Among his losses was his new regimental uniform.) Further along the Millstone, where it crossed the Post Road near Kingston, Scudder’s brother Lemuel owned mills which were also destroyed by the British. A third brother, Nathaniel Scudder 1751, was a physician who became a colonel in the militia.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Bill, Alfred Hoyt. The Campaign of Princeton, 1776-1777. Princeton University Press, 1948.

Smith, Samuel Stelle. The Battle of Princeton. Philip Freneau Press, 1967.

Stryker, William S. The Battles of Trenton and Princeton. Houghton, Mifflin, 1898.

Wertenbaker, T. J. “The Battle of Princeton,” in The Princeton Battle Monument. Princeton University Press, 1922.

2 Responses

Richard Mawhood

4 Years AgoA Scientific Analysis

For an authoritative and very comprehensive scientific analysis, see the Battle of Princeton Mapping Project: Report of Military Terrain Analysis and Battle Narrative, Princeton, New Jersey, prepared for the Princeton Battlefield Society by John Milner Associates, Inc., September, 2010.

Étienne Johannes Sharp

9 Years AgoYou've rather conflated...

You’ve rather conflated “British” with “English” throughout, which diminishes any academic credence the piece had.