Best Friend

Lem Billings ’39, confidant to the Kennedys, was always present — in the background

Lem Billings ’39 was John F. Kennedy’s funny friend. Funny as in humorous, sure: Lem was always quick with a joke, especially at his friend’s expense. “Haven’t you found any girl that will have you, Kennedy?” he jabbed in a 1945 letter. “You know, you’re no spring chicken any longer — 28 in a couple of weeks, as I recall — and when I last saw you your hairline was receding conspicuously.” Lem, in contrast, reported “looking very well, with a bronzed and stern appearance.”

Lem, said Ethel Kennedy, “saw the ridiculousness of the human condition, and parodied it until tears came down his cheeks and an asthmatic coughing fit ended his glee.” Bobby Kennedy Jr. remembered him this way: “Whenever I felt lonely, or sad, or left out, I would call Lem and laugh.”

But Lem was also funny in other ways. Funny as in different. Funny as in flamboyant. Funny as in queer.

Which is to say: Have you heard the one about JFK’s gay best friend?

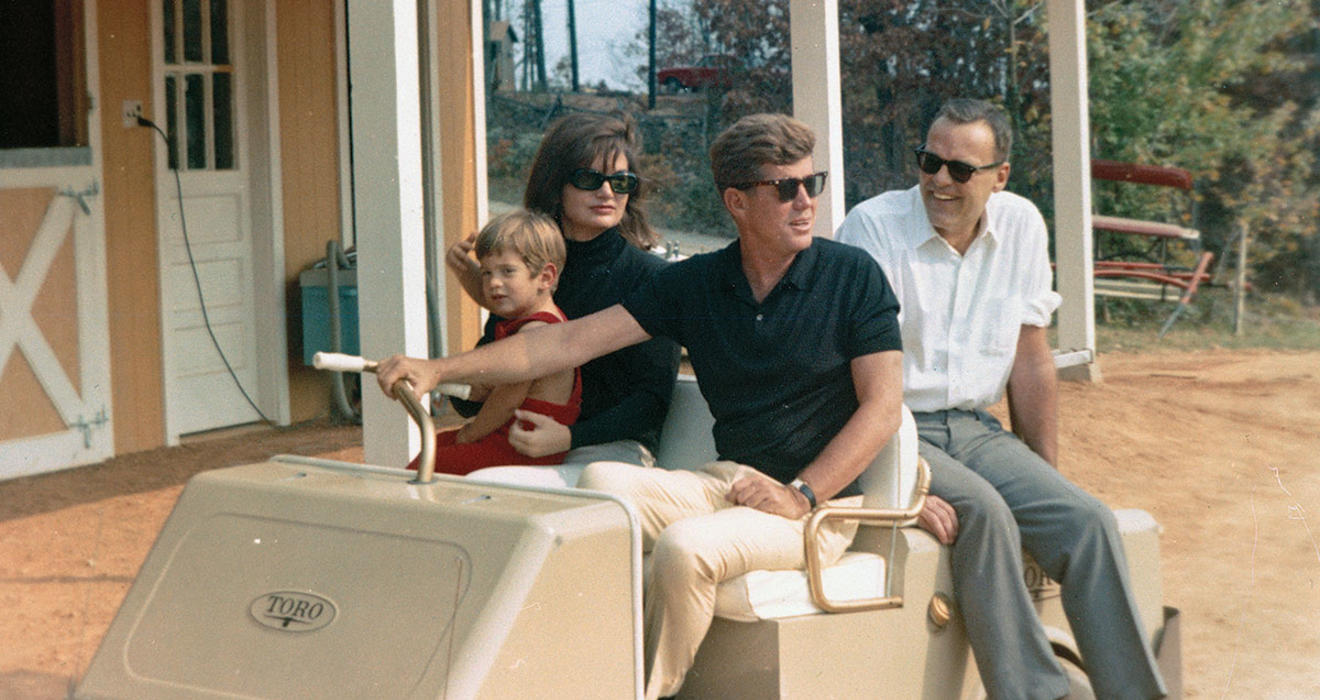

Lem Billings was there. He walked with John F. Kennedy through the halls of Choate and Congress; he nursed Jack through sickness (and hangovers) from Princeton to Washington, D.C. His was such a constant presence at the Kennedy compound in Hyannisport that Ted Kennedy later remembered, “I was 3 years old before it dawned on me that Lem wasn’t one more older brother.” An exasperated Jackie Kennedy once complained that “Lem Billings has been a houseguest every weekend since I’ve been married.” Sure enough, he had his own bedroom at the White House.

If he had been a heterosexual man, you would have seen him on TV, burnishing the Camelot myth alongside JFK protégés like Ted Sorensen and Arthur Schlesinger Jr.

Instead, Lem could only be Lem: 6 foot 2, stocky and asthmatic, with a high-pitched voice and a piercing laugh. He hated the Kennedys’ afternoon football games but came alive at cocktail hour, belting out bawdy Mae West numbers at Jack’s behest: “Make that low-down music trickle up your spine, baby / I can warm you with this love of mine / I’m no angel.” He loved art as much as Jack loved politics, even dragging a college-age Jack to Florence to admire Michelangelo’s David. (Lem described it in his journals as “the most beautiful statue I’ve ever seen or hope to see.” Jack merely noted that he was “quite impressed.”) Two decades later, President Kennedy took his friend along on his administration’s first trip to Europe. While Jack fretted about how to impress Nikita Khrushchev, Lem was in charge of buying objets d’art to give to the Soviets as diplomatic gifts.

There are lots of little stories like this — stories where Lem stands proudly in the background as Jack commands the world stage. Still, I have sometimes noticed gay men dropping Lem’s name like a charmed token. Some treat his friendship with JFK as a badge of honor: Lem was here, they marvel, he was queer, JFK got used it. Others fashion him an emblem of gay heartache — of that formative, unrequited yearning most queer boys feel for a straight friend.

Gay history in America has often been hidden history. But now that the country is more open to queer identities, Lem deserves his moment in the light. He may not have been a famous, great American, but he lived a great — improbable, historic, melodramatic — American life.

Lem’s moment almost arrived in 2007. That year, the journalist David Pitts released Jack and Lem, an account of the pair’s 30-year friendship that drew on exclusive access to their correspondence. Unfortunately, the publishing company in charge of releasing Jack and Lem folded just as the book was set for release. Pitts’ work went largely unpublicized and unreviewed. It’s nevertheless an important study — most of the anecdotes in this article are drawn from it, with the author’s permission — and it’s by reading Jack and Lem that the contours of an extraordinary friendship emerge.

Jack and Lem met at Choate in 1933. Kirk LeMoyne “Lem” Billings was a bumbling giant, the offspring of a prominent but cash-poor Protestant family. Jack was small and inquisitive, a scion of the Catholic, new-money Kennedys. In Lem, Jack found a confidant and caretaker; Jack was frequently ill while at Choate, but Lem kept his spirits high with jokes and gossip. Lem, meanwhile, relied on Jack not just for friendship, but for stability. He’d arrived at school reeling from the recent death of his father, which left the family destitute. He was also newly separated from his siblings: His sister Lucretia recently had married, and his older brother, Frederic “Josh” Billings ’33, had moved to England to study on a Rhodes scholarship. Lem was grateful for the chance to embed himself in the Kennedy clan. “Things were in upheaval,” says his nephew Frederic III ’68. “The Kennedys provided family and support and so forth.”

Lem always put Jack first in life. Jack, meanwhile, put Jack first — but to his credit, never left Lem behind. After Choate, the pair briefly attended Princeton together in the fall of 1935. Then Jack got sick and decamped to Harvard. They reunited a year later for a summer road trip through Europe, adopting a dachshund named Dunker together while motoring through Nazi Germany. Then came graduation, war, and separate postings — Jack in the Pacific, Lem in North Africa. Afterward, Lem embarked on a long career in advertising and cultivated a passion for interior design. JFK plotted his political career.

Whenever Jack needed him, Lem would rush to his friend’s side. In 1946, Lem moved to Boston to be with Jack for his friend’s first congressional run. In 1960, he helped run Jack’s campaign for the Wisconsin presidential primary. Later, as First Friend, Lem stayed with Jack during the Bay of Pigs and Cuban missile crises. Through it all, Lem had a singular ability to put Jack at ease. “It’s hard to describe it as just friendship; it was a complete liberation of the spirit,” Eunice Kennedy Shriver recalled to Pitts. “I think that’s what Lem did for President Kennedy: President Kennedy was a completely liberated man when he was with Lem.”

In keeping with this liberated spirit, a large portion of Jack and Lem’s correspondence — there’s no way around it — centers around sex. While at Choate, the friends traveled to New York together to lose their virginity to a prostitute. (Lem didn’t go through with it, he later told a friend.) Later, Pitts writes, “Jack’s dates would be managed by Lem,” who would make and cancel arrangements and bring women to Jack when Jack was ready for them.

Did Jack ever know Lem was gay? Almost certainly, Pitts demonstrates, even if JFK might not have named it as such. One telling moment occurred in 1934, at Choate. As Pitts tells it, there was a tradition at Choate where “boys who wanted sexual activity with other boys ... exchanged notes written on toilet paper to indicate their interest. Toilet paper was used because it could easily be swallowed or discarded to eliminate any paper trail.” Lem sent Jack a toilet-paper note. Jack’s response was captured in a letter written from a hospital in Rochester: “Please don’t write to me on toilet paper anymore. I’m not that kind of boy.” He then continued detailing his medical ordeal as if nothing major had happened. “My virility is slowly being sapped,” he complained. “I’m just a shell of the former man.”

Lem’s toilet-paper message wouldn’t necessarily have been received by JFK as a declaration of strict homosexuality — such propositions were common enough in boarding schools at the time. But Lem did go on to have (furtive) homosexual relationships with several men throughout his adult life, Pitts reports, and spoke of his homosexuality to gay friends later in life. And though Lem never publicly declared himself a gay man, Pitts’ interviews with Kennedy staffers indicate that Lem’s homosexuality was treated by White House personnel as an open secret. “This goes back to the way that homosexuality was treated at the time, which was as something that liberal people tolerated but didn’t want to talk about. So he was kind of cast to the sidelines because of that,” Pitts says. For Lem, the price of Jack’s friendship was absolute discretion, if not repression.

Sex, and sexuality, are key to understanding JFK’s closeness to Lem. Jack’s sexual conquests — before and during his presidency — are legendary and legion. “Women were kind of sex objects to JFK, not to be taken too seriously,” Pitts says. So it makes sense that his closest relationships were with men. And among these men, it figures that JFK’s closest relationship of all would be with a man unburdened by the demands of married life or fatherhood. A man who’d be able to devote himself totally to his friend: a closeted, unmarried homosexual like Lem.

When David Pitts set out to write Jack and Lem, he was mainly interested in Lem Billings’ life for what it said about John F. Kennedy’s. I was curious about what Lem was like when he wasn’t in Jack’s shadow. I took a train to Princeton to find out. His four years at Princeton, I figured, were his before years: that brief period before he became the official best friend of a war hero, a congressman, a president, a martyr. College was a time when he was separated from Jack and — perhaps — had to forge a separate identity for himself.

The most prominent artifacts of Lem’s time at Old Nassau are, of course, those related to his famous college roommate. A cheeky Chrismas card from Lem, Jack, and a third Choate boy, Ralph “Rip” Horton ’39, who lived together in Reunion Hall from October to December 1935. A snapshot of Lem, Jack, and Horton in their preppy best outside a Princeton drugstore. A framed photo of Lem and Jack at Ivy Club, displayed in that club.

From there, the archival trail grows more faint. Lem had friends at Princeton, but he was not a joiner. Unlike the classmates who surrounded him in the Class of 1939 Nassau Herald, Lem was not a member of The Daily Princetonian, nor the Triangle Club, nor Whig-Clio. He passed on student government, Orange Key, and the German Club. His sole lasting affiliation was his eating club, Ivy. Lem’s low profile is particularly noticeable when set against that of his older brother. While at Princeton, Josh was captain of the football team, president of the Undergraduate Council, and a winner of the Pyne Prize.

Princeton-era Lem comes alive only in his senior thesis, written about Tintoretto for the art history department. Lem had seen works attributed to the Venetian master while traveling with Jack in Europe. He concluded that Tintoretto had been unfairly overshadowed by “Venice’s apparently unapproachable favorite,” Titian. It was Tintoretto, not Titian, whose work “came from his innermost soul,” that was “beautiful not only because of a splendid surface, but also because of the presence of feeling far beneath the surface,” Lem wrote. It’s impossible to read Lem on Tintoretto’s hidden depths without wondering about the writer’s own subsumed feelings of longing and inadequacy: “[As Tintoretto] himself expressed ... ‘The further you go in, the deeper is the sea.’”

David Pitts hadn’t visited Princeton while researching Jack and Lem, so I called him and shared what I’d found. He wasn’t surprised by the lack of material. Lem spent most weekends in college away from Princeton, visiting Jack, Pitts explained: “I found all the telegrams. If they weren’t meeting in Cambridge, they were meeting in New York.” When Jack and Lem weren’t together, they were writing each other teasing letters.

Even at Princeton, it seems, Lem’s first priority was his best friend, Jack. At Choate, Lem had been captain of the crew team. At Princeton, Lem briefly rowed on the freshman boat, but that soon took a backseat to his Kennedy family obligations. “When spring vacation came around, the team was going to Florida to row because Lake Carnegie was frozen,” said Lem’s nephew Frederic. “But my uncle was invited to go to Hyannisport with the Kennedys. So he told the crew coach that that’s what he was going to do. And the crew coach said, ‘Well, when you return, you won’t have a seat in the boat.’ That was the end of his crew career at Princeton.”

As for how, and whether, Lem might have found an outlet for same-sex desires while on campus, one can only guess. Queer historians paint the 1930s as a time of repression at Ivy League universities. Look at photos of students from the 19th century, Yale history professor George Chauncey notes, and you’ll see that they’re all over each other. By the 1920s or so, the poses had stiffened out. Not coincidentally, psychoanalytic theories had entered public consciousness for the first time after World War I, leading people to newly consider sexuality, and homosexuality, as “identities” central to their being. Male intimacy gradually came to mean something that it hadn’t meant before. At best, it was a phase that upper-crust boarding-school boys could grow beyond. For those who couldn’t shake them, though, homosexual acts transmuted during this age into a character flaw — suggesting to psychologists, and to the public at large, a tendency toward depravity and criminality.

That’s not to say that homosexuality wasn’t present at Princeton and its peers in the 1930s. (Chauncey, for instance, has surfaced reports of an all-gay Yale fraternity at this time.) But many students with same-sex leanings had no one to confide in. One alumnus wrote this in his 50th-reunion yearbook: “As a homosexual member of the Class of 1938, who, perforce, had to remain in the closet throughout his university years, I look back with mixed feelings at my time at Princeton. Throughout my four undergraduate years I imagined I was the only gay person in the class. ... In truth, I feared if my sexual orientation were ever discovered, I would be expelled from the university.”

As Lem moved away from Old Nassau and into the world, the consequences for homosexual behavior remained severe. Soldiers fighting in World War II could be, and were, court-martialed for same-sex relations. In the 1950s, Sen. Joseph McCarthy led witchhunts to out homosexuals in the Army and the State Department. Lem would have been well acquainted with this threat: Robert Kennedy briefly worked for McCarthy during the Red Scare, and Eunice and Pat Kennedy both dated him.

Though McCarthy eventually disgraced himself, the dangers of being outed persisted well into the 1960s. Had Lem been publicly exposed as gay during that time, it would have been a major scandal for the Kennedy White House. President Kennedy could have lessened this risk by distancing himself from Lem. But Jack stayed loyal: “He took political chances to maintain his friendship with Lem,” Pitts says, although Kennedy himself might not have seen it as quite so grand a gesture. To him, Lem was first and foremost his best friend. A “don’t ask, don’t tell” attitude toward homosexuality (common among upper-crust Americans at that time) suited Kennedy equally well in the White House as it had at Choate.

JFK’s murder in 1963 shattered his best friend. “In many ways, Lem thought of his life as being over after Jack died,” Robert Kennedy Jr. told Pitts. Lem continued to play the clown in public, especially when around Jack’s children, nieces, and nephews, to whom he was devoted. But behind the scenes, friends said, he suffered from mood swings, depression, and heavy drinking.

Lem died of a heart attack in 1981, at age 65. The young generation of Kennedy men served as the pallbearers at his funeral. Eunice Kennedy Shriver memorialized him fondly: “I’m sure he’s already organizing everything in heaven so it will be completely ready for us — with just the right Early American furniture, the right curtains, the right rugs, the right paintings, and everything ready for a big, big party. Yesterday was Jack’s birthday. Jack’s best friend was Lem, and he would want me to remind everyone of that today. I am sure the good Lord knows that heaven is Jesus and Lem and Jack and Bobby loving one another.”

Lem’s family didn’t see his life quite so rosily. “All of them thought he was far too close to John Kennedy and far too attached to him, that [Jack] was almost an obsession to him,” says Pitts. They saw Lem’s life as tragic because Lem had sacrificed so much to become close to Kennedy. Today, Lem’s nephew says he’s not “necessarily proud or unproud” of his uncle’s relationship with JFK. “My uncle was not someone you could have a reasonable conversation with about what was going on with the Kennedys. He did not want to hear one negative syllable, and there were a lot of negatives going along.”

There’s no easy way to compare Lem’s life to the ones he might have lived. Some gay men of his era suffered through empty marriages and ruinous affairs rather than come out of the closet; others came out and suffered terrible consequences. More happily, some came out and found romantic love with other men, of the kind that Jack could never give Lem. Few gay men will ever have the option that Lem did: to serve as jester, confidant, and friend to one of history’s most storied figures — at the cost of keeping his private life utterly private.

Because of this compulsion toward privacy, Lem’s life has been inscribed in history as little more than a footnote to his friend’s. But on this matter, at least — the question of whether his life was better or worse for having been devoted to John F. Kennedy — Lem deserves the last word. “Jack made a big difference in my life. Because of him, I was never lonely. He may have been the reason I never got married. I mean, I could have had a wife and a family, but what the hell — do you think I would have had a better life having been Jack Kennedy’s best friend, having been with him during so many moments of his presidency, having had my own room at the White House, having had the best friend anybody ever had — or having been married, and settled down, and living somewhere?”

David Walter ’11 is a freelance journalist in New York. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Economist.

4 Responses

Michael Collins ’67

8 Years AgoA fascinating article. It reveals...

A fascinating article. It reveals so much about what is hidden or publicized, then and now.

Norman Ravitch *62

8 Years AgoLem Billings ’39’s Life

Published online July 6, 2017

The story about Lem Billings ’39 and JFK was very interesting and even moving (cover story, April 12). I have one additional comment, probably to be regarded as politically incorrect.

Billings remarked (at the end of the story) that had he married and settled down, he would not have been happier than he was as JFK’s best friend. I wonder, if the attitude toward gay men today had been the case when he was young, whether he would have been any happier having come out of the closet. I suspect that it is not only social and legal conventions that make homosexuality difficult; I think homosexuality will necessarily result in unhappiness no matter how society feels about it. It involves feelings of abnormality and difference that no law can abolish, no psychologist can overcome, no change in attitudes can remedy. It is inherent in the soul of the homosexual: that he is not like most people and cannot be. I say this with no negative opinion about homosexuality except that it is a misfortune no matter what anyone says about it.

Charles Scribner III ’73 *77

8 Years AgoJFK’s Loyal Friend

I got to know Lem Billings ’39 (cover story, April 12) in my Princeton days through my wife’s cousin Francis McAdoo ’38, a close friend of Lem’s and JFK’s at Princeton. When Lem learned that I was getting my Ph.D. in art history, he launched into an animated account of his senior thesis on Tintoretto. When I found and read it in Marquand Library, I was nonplussed. I had expected Lem’s unbridled enthusiasm but not the solid scholarship, the elegant, passionate prose, and the depth of art historical insights. It might have been written by a young Bernard Berenson.

Lem had marshaled all his critical powers to establish Tintoretto’s primacy among Venetian painters (move aside, Titian!). Most poignant was his intimate identification with the old Tintoretto, through whose paintings Lem conjured up the inner thoughts, aspirations, and spiritual resonance of the artist approaching death.

Like Merlin, Lem lived his life backwards. As he himself grew old and frail in health, Lem grew ever younger in spirit and outrageous in behavior, playing Falstaff to a succession of Prince Hals with the surname Kennedy. Yet as a youth he had revealed an uncanny insight into the soul of an aging master. For Lem, both youth and age were fused in a man of extremes who reveled in contradictions — a man too complex to be fully understood. But for me, a hint of an explanation came through his early self-revealing portrait of Tintoretto, who was a master of chiaroscuro — of shadows and light.

Gary Walters ’64

8 Years AgoJFK’s Loyal Friend

What a shocker. And what a pity that David Pitts’ book attracted little attention when it was released. Perhaps it now will. At Princeton in the fabled ’60s, the consequences of coming out were as described in David Walter ’11’s article. But as always, the rules were easily circumvented, though with some risk. On the day of the Dallas shooting, a friend and I were staying at the Biltmore in New York and saw that tragedy televised as we made love. Where was Lem Billings on that particular day and place?

Lem was the one person with whom Jack could actually be honest about sex, it would seem, and without censure. I don’t agree with Mr. Walter, however, when he writes, “it figures that Jack’s closest relationship of all would be with a man unburdened by the demands of married life or fatherhood ... a closeted, unmarried homosexual like Lem.” I think, as the ever-more-complex history of gay love is revealed, that this was a love affair of the very sort we find in ancient Greece and elsewhere: Male bonding with or without sex, an understood intimacy and an absolute loyalty, particularly in fights, not to be found with female friends or lovers — or not then.

In this regard, times have changed. The media can’t leave anything alone. The delicate, the intimate, and the private are eviscerated. All the more reason to admire this piece by Walter, who gives the facts, the preppy context, but leaves the relationship to stand within a personal and necessary ambiguity.