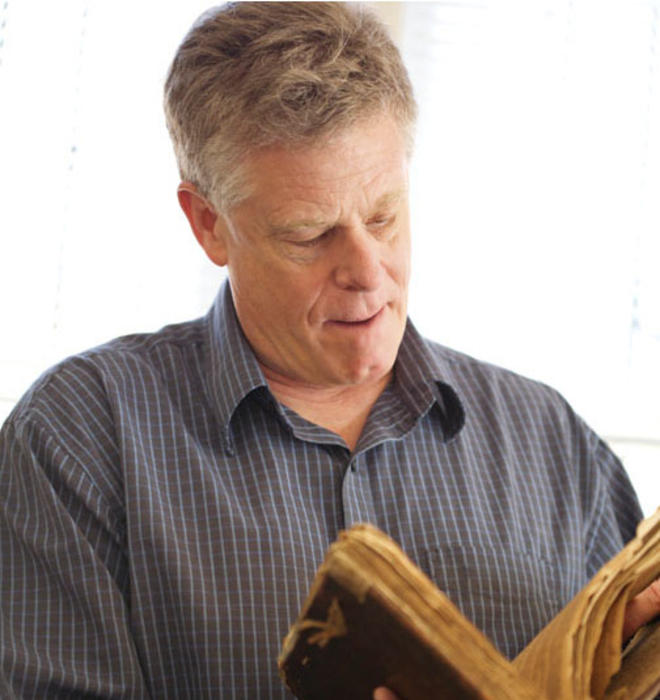

ON BOOKS: The bookman

Internet, be damned: Nicholas Potter ’73 sells books the old-fashioned way

On Palace Avenue in Santa Fe, Nicholas Potter ’73 has been selling used books for more than 35 years, just down the street from the 400-year-old Palace of the Governors and St. Francis Cathedral. Bookselling is in Potter’s blood. His father was a bookseller in Chicago before the family moved to Santa Fe in 1969. “Summer vacations I worked at my dad’s bookshop,” says Potter, “because I thought it was a cool life with interesting people. ... As a history major and English minor, books meant something to me.”

That has never changed in all the years since Nicholas Potter, at 23, took over the shop after his father’s death. “From day one, I realized it was exactly what I should be doing with my life — the interaction with people and exposure to ideas and concepts,” he says. Today, despite radical changes in publishing, bookselling, and retailing in general that have forced other booksellers to close their shops — “Believe me, the last couple of years have been very tight,” Potter says — he has resisted major changes to his way of doing business.

A self-described “old-school bookman,” Potter works amid shelves and stacks and boxes of used books. Classical or jazz music plays in the background. While other independent booksellers have employed the Internet for promotion and sales, Potter has made few concessions to the electronic age. There is no computer in sight, no cell phone ringing, and although he does use email, Nicholas Potter, Bookseller, does not have an active website and neither lists nor sells books on the Internet. “It is just counter to the way I’ve always wanted to do business,” he says. “It’s not browsable, it’s not personal. I want to have a relationship with the person who’s buying the book. Every day I have the pleasure of putting a book in the hands of someone who is going to appreciate it. I’m sort of the keeper of that book, until I find the right home for it.”

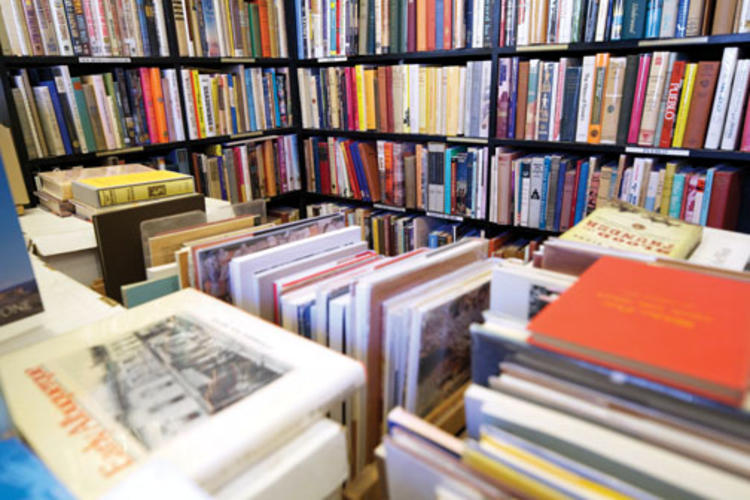

Potter is a general used bookseller, not a rare-book dealer, not a specialist. Wander the six rooms of the old adobe house that he rents for his business and you’ll find a regional room of New Mexico and Southwestern titles; another of literature; a room of art books that reflect Santa Fe’s long and vibrant art scene; a room for history and travel; cookbooks in the old kitchen; and Potter’s office up front. Doorless closets throughout are packed with books: Latin American titles, leather-bound books, music, a “metaphysical closet” in the back. Though the world has moved toward downloaded music “content,” Potter sells used CDs near the register — “a good impulse item because they’re $10 or under” — since Santa Fe has an extensive performing-arts community. A few photographs are for sale, but you won’t find maps, prints, or other paper items, nor any best-sellers, business titles, or self-help books. There are no author readings, poetry open-mike nights, or book-club meetings.

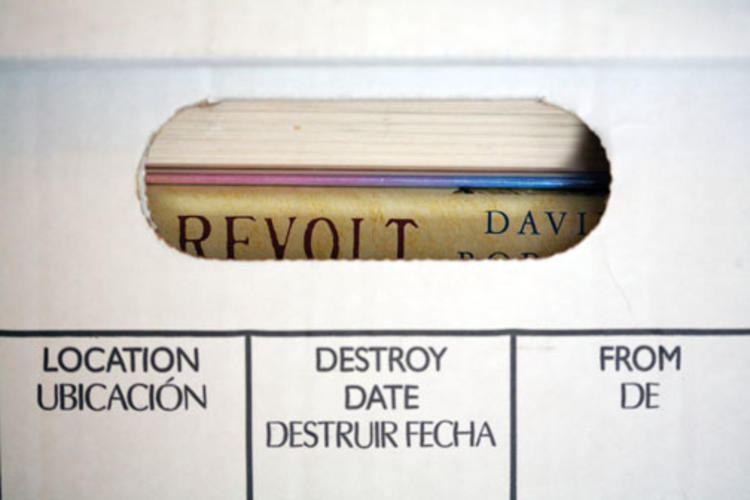

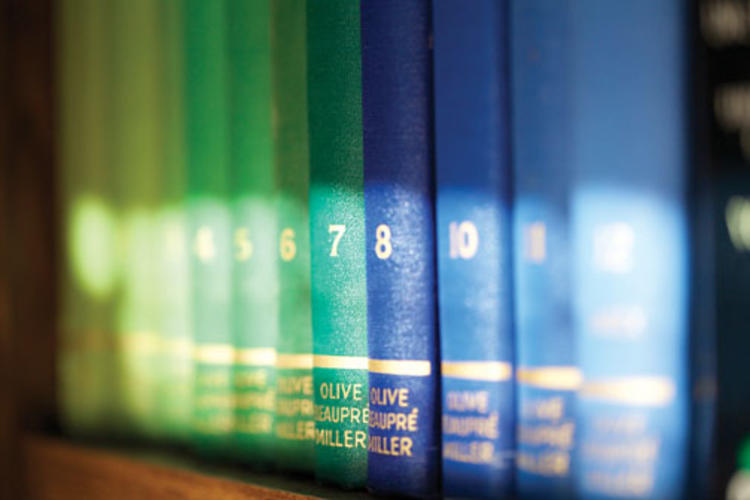

Potter does not sell new books. The used-book business, he says, is “much more infinite. ... In used books, not only is there the breadth of virtually everything, but there’s also the history of it.” A letterpress first edition of Leaves of Grass can resonate in ways impossible for a contemporary paperback to achieve, much less a download viewed on a Kindle or iPad, Potter says, with rewards that flow from the book’s aesthestic (leather binding or some aspect of book-making that is no longer being employed), history, and perspective: “It’s about either seeing how someone else viewed something at a different time, or about something that changed the course of time — this is an important book because. Not necessarily a popular book, not necessarily a successful book, but important. Important in mankind.”

Potter estimates he has 12,000 titles in the store and another 25,000 in storage. He can’t turn them over like Wal-Mart or Target can, though he has outlasted the local Borders, one of the chain stores that drove many independent bookshops out of business. To make room for inventory, which is necessary but expensive to maintain, he recently held a sale — his first since 1997. But the ascent of online book sales and e-books is a challenge of a different order, since efficient overhead, inventory, and delivery systems offer consumers “products” more conveniently, at better prices. Book sales actually increased in 2009 and 2010, according to the Association of American Publishers, but much of that growth came from e-books. (Bookstore sales were unexpectedly strong during the holiday season, The New York Times reported.) Amazon announced this year that it sells more Kindle books than hardbacks and paperbacks combined.

“Obviously, things are changing rapidly,” says Potter. But he insists that traditional booksellers offer something that the online book market cannot: the ability for people to browse the shelves. It is, he says, analogous to Firestone Library’s open stacks. “I think all of us can come up with some experience where we didn’t know what we were looking for, [but it] came our way through browsing.” Potter believes that such serendipity cannot be replaced by computer-generated “personal” recommendations and reviews by unknown customers. “Heart and soul and personal passion are things that are not quantitative,” he says. “You need to be able to browse. Whether you check the index, look at how well illustrated [a book] is, or read a paragraph and see the writing style of the author — there are so many tactile, subjective, personal aspects in the book. You can wander and explore beyond your horizons. Maybe you pull out a book, and the one that is next to it on the shelf is actually the one you are meant to see.”

It matters greatly to Potter that he is part of a community, and that is his hope for the future. Though Santa Fe lacks a major university that can support a used bookstore and has a permanent population of only 68,000 (a number that swells significantly with book-loving tourists each summer), Potter relies on his shop’s reputation and the relationships he has developed over decades in the business. Writer Cormac McCarthy, a Santa Fe resident, has been buying nonfiction books from Potter for 35 years. Filmmaker Ethan Coen ’79 shopped in the store when he was in New Mexico to film McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men. “I have a lot of locals I see every day whom I don’t necessarily sell something to, but we’ve become friends, and this is a place where they stop. I want them to feel like they are welcome. A store, as opposed to a website, has always been a place. It has a personality; it is an interactive experience.”

Potter has “heart and soul and passion” for books. He and other iconoclasts fully recognize the trends — bottom-line consolidation of publishing, the demise of independent (and now chain) bookstores, the rise of e-books and virtual storefronts — but they carry on nonetheless. “If the screen becomes the way we get our information,” says Potter, “the only way that we will be able to pursue something is to know what it is we want. By definition that narrows our horizons. Which would be ironic — this tool [the Internet] supposed to give us the entire world at our fingertips. ...

“The idea in a used bookstore is you never know what you might find — the store has its own identity and personality because it reflects the personality of the proprietor,” he says. “What I’m doing may not make a great living, but it is a great life.”

Michael Pettit ’72 is the author of Riding for the Brand: 150 Years of Cowden Ranching, which won the New Mexico Book Award for Southwest History.

No responses yet