Not long ago, newspapers and magazines considered it their cultural duty to guide readers through the torrent of books that American publishers sent forth. But apart from a few stalwarts, those periodicals — struggling as they are in a Web-oriented world — have decided that book reviewing doesn’t pay. They’ve shed or radically shrunk their literary sections and laid off editors and critics, leaving readers to look elsewhere for recommendations and engaging writing about books. “Twenty times as many titles are published each year than were a quarter-century ago, and we have one-twentieth of the serious print book reviews,” notes the Los Angeles Review of Books, a new website founded for the purpose of filling that gap.

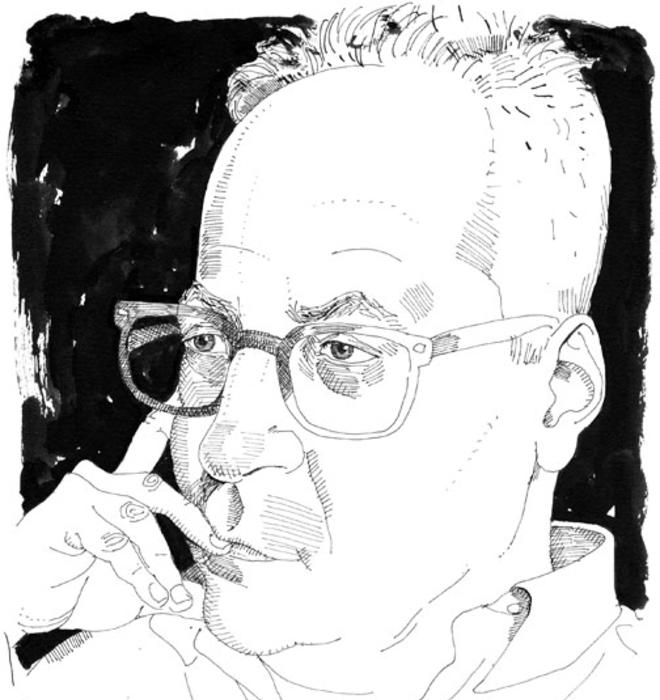

What’s rising in the place of the newspaper book section? James Mustich ’77 presides over one alternative: the Barnes & Noble Review, the book chain’s surprisingly highbrow online book review, whose regular contributors include Robert Christgau, invariably called the dean of rock criticism; A.C. Grayling, the British philosopher and public intellectual; and Michael Dirda, the Pulitzer Prize-winning critic for The Washington Post. “We started this when the decline in newspaper and magazine book reviews was apparent, but that was more fortuitous than strategic,” Mustich says. “Over the years our role as a substitute has become more conscious.”

Other fresh outlets for information about books include the free online quarterly Toronto Review of Books, which debuted in September; Goodreads.com — like Facebook for book people, with 6.5 million members (a figure that’s doubled in under two years); and even NPR, which has decided to make books a prime focus of a revamped website. “Because we are noncommercial, we feel a responsibility to step forward and fill the gap,” says Joe Matazzoni, a senior supervising producer at NPR. But he stresses it was an opportunity as well as a responsibility: From late 2009 to fall 2011, as NPR retooled its site to focus on “book discovery,” it saw its books-related traffic double, to 1.8 million monthly views.

To be sure, some traditional publications retain their power. One 2010 study found that a positive review in The New York Times Book Review increased sales by 32 to 50 percent. For unknown authors, even a negative review in the Times increased sales — though more famous authors took a hit. “You have now killed my book in the United States,” wrote Alain de Botton, on the website of the New York-based writer Caleb Crain, after Crain panned de Botton’s The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work in 2009 in the Times. “So that’s two years of work down the drain in one miserable 900-word review ... I will hate you till the day I die.”

While other newspapers eliminated book sections, The Wall Street Journal launched one a year ago; and then there’s Oprah, whose book club turned modest sellers into juggernauts from 1996 to 2010, and who surely retains some of that clout despite her move this year to cable television.

But the decline of book-review sections has spawned a whole new literary ecosystem: a proliferation of blogs, Twitter feeds, and reviews posted by ordinary readers. Last summer, despairing of review attention, the University of Michigan Press serialized two novels on Facebook. (The Princeton University Press blogs and posts almost daily on Facebook.) Perhaps the most outlandish attempt to get attention for books comes in the form of the book “trailer,” modeled, all too closely, on the over-the-top previews in movie theaters. Potential customers of author Seth Grahame-Smith’s Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter got to see an actor playing Abe take an ax to a fanged White House intruder. To what extent this fuels sales is, as yet, unclear.

When it comes to connecting people and books, Mustich makes an interesting case study. He is a lifelong literary middleman who had to reinvent himself, or at least reorient himself, after the rise of e-commerce. Growing up in Westchester County, N.Y., Mustich used to head to Greenwich Village to peruse its used bookstores. At Princeton, where he majored in English, he wrote some poetry. He recalls a seminar with the late professor Robert Fagles, who just had finished his translation of the Oresteia. “We went through that great trilogy of tragedy line by line with him, and that was just as good an advertisement for the excitement of text and of all it can conjure up as anything I’ve ever done,” Mustich says. Another highlight was a seminar with English professor Maria DiBattista, whom he remembers discussing the themes and tropes of One Hundred Years of Solitude, only to put down her notes and exclaim, “Oh, it’s just a great book to read! It’s why we got into this in the first place.”

In 1986 Mustich founded an artisanal mail-order book catalog called A Common Reader. He and his staff wrote loving descriptions of books they had long adored or just encountered, with few glances at the best-seller list. Books were grouped idiosyncratically, under such rubrics as “Connoisseurs and Confidence Men.” That one included a biography of the art historian Bernard Berenson, William Gaddis’ novel The Recognitions, and books about art forgery and art theft. “Books become tokens of places we’ve been, people we’ve known, wishes fulfilled and maybe forgotten,” explained the July 1993 issue. “In A Common Reader, we hope you will recognize some significant volumes from your own past, and be introduced to some intriguing strangers as well.” The company also republished out-of-print books under the imprint The Akadine Press. Among Mustich’s proudest accomplishments is reviving A Mass for the Dead, a memoir by William Gibson, author of the play The Miracle Worker. Without the book, Mustich told his subscribers, “my sense of self, family, and world would be unrecognizable to me.”

“Jim and his colleagues would have write-ups of the books they were selling that were just terrific mini-essays and appreciations of a great variety of authors,” recalls Dirda, the critic, who still keeps an eye out for Akadine Press volumes in used bookstores. “It struck me that this was a company that showed really remarkable taste.”

But as online retailers like Amazon grew more popular, it became harder and harder for Mustich to compete on price. And it wasn’t a good sign that, on an e-commerce site, Mustich could click on a title he’d recommended and see that online buyers were purchasing books A Common Reader had grouped with it. “There was no reason for these books to be put together, except that we had thought to do so,” Mustich says. “In that sense, [the Internet] was an efficient and powerful enemy.” The company declared bankruptcy in 2006.

Fortunately, Mustich and A Common Reader had an influential fan and longtime acquaintance, the then-CEO of Barnes & Noble, Steve Riggio, who recruited Mustich to start an online review. Mustich says that his marching orders were refreshingly non-bottom-line-oriented: “Create a space,” Riggio told him, “where you or I would go to find something interesting.” It debuted in 2007.

N. Heller McAlpin ’77, a longtime book reviewer who has watched with trepidation as the places she writes for slashed staff and space, says the Review’s appearance was most welcome. “When word got out, it was every critic’s dream to have a site for such intelligent reviews,” she says. Critics can write reasonably long (1,000 words or so), and there are features like “Five Books” on a theme, interviews, and a roundup of literary events on that day’s date in history.

Mustich won’t discuss traffic or sales figures, but says that when the Review sends out its weekly emails highlighting new reviews, sales for even noncommercial books routinely leap into the top 50 on Barnesandnoble.com. “It’s clear that people are treating the emails like they used to treat the Sunday book-review section, circling books and deciding what to buy,” he says.

Some observers think that so-called “crowdsourcing” will replace the traditional review. Are not the opinions of hundreds of readers, on Amazon.com or Barnesandnoble.com, at least as valuable as the squib of a critic in your local newspaper or favorite magazine? Michael Luca, an assistant professor at Harvard Business School, has studied online reviews of restaurants and books, and he has some doubts about that hypothesis. Restaurant reviews do, in fact, seem to bring fresh efficiency to a confusing market, his research suggests: Good restaurants get discovered earlier and bad ones close more quickly. “But people generally agree which restaurants are good, at least within a category,” Luca says. Preliminary work he has done on book reviews finds that books that win literary prizes — to take one example — tend to get lower ratings from ordinary readers than from professional critics. Crowdsourcing may identify the most broadly popular works, but it’s less likely to identify works of great merit that puzzle or turn off a significant minority.

Goodreads attacks that problem in part by encouraging people to share book recommendations online, not just with their friends, but also with strangers who share similar literary tastes. The average user has 140 books on his or her virtual shelf, which can be organized by category, and there are 145 million book ratings overall. The approach is popular, but in September, the company also rolled out a book-recommendation algorithm, partly modeled on Netflix’s formula for movies, to provide suggestions based on a user’s tastes. It’s for people who want recommendations right now, “without doing a lot of work,” says Kyusik Chung, Goodreads’ vice president of business development.

Goodreads is for-profit — “Our main business model is connecting people with books and getting the marketing dollars in the middle,” Chung says. Nonprofit book-review sources offer another alternative, but they, too, are affected by the money woes facing traditional media. NPR’s attempt to pick up the slack in book coverage has only one-and-a-half positions devoted to books, although reporters and editors from on-air shows also contribute. Matazzoni, the senior producer, acknowledges “a continuing sticky economic situation.” The Los Angeles Review of Books relies on the University of California, Riverside for office space — Tom Lutz, a creative writing professor there, is editor-in-chief — and is seeking donors in order to reach its goal of publishing a print version in early 2012. It aspires to be a West-Coast-inflected variation on The New York Review of Books, with a mix of reviews and essays.

“In a perfect world, we would be ‘extra,’ in the way people read The New York Times Book Review and then read a longer or more academic or more critical take in The New York Review of Books,” says Evan Kindley, The Los Angeles Review’s managing editor and a graduate student in Princeton’s English department. “But the thing that is up in the air is whether newspapers are even going to be a part of it.”

Talk about periodicals and online book reviews omits one important way that people get introduced to new books: bookstores themselves. “Bookstores are a very underappreciated mechanism of book discovery,” says Michael Norris, a senior analyst with Simba Information, a consultant to media and publishing companies. In a recent survey of 100-plus independent stores, Norris says, 40 percent reported that former customers of theirs return to browse “often” or “very often” but leave to buy online. “It goes beyond independent bookstores stomping their feet in disgust,” he says. “It’s a pending crisis in the publishing industry because you have the entities who are paying for the showrooms not getting a piece of the action when the sale is made.”

Independent stores are fighting back, partnering with Google, for example, which gives them a percentage of e-book online sales, and deploying print-on-demand machines, which give instant access to some back titles. They also are playing up a role they’ve always served: providing personalized recommendations. Politics and Prose, in Washington, D.C., goes so far as to sell a “concierge” service, through which subscribers each month get a book that has been handpicked by a staff member. But Lissa Muscatine, co-owner of the store and a former top aide to Hillary Clinton, cautions against making too much of that special offering. “Bookstores themselves are a concierge service,” she says.

Though he now runs an online book-review site, Mustich says there always will be a place for the serendipitous discovery that physical bookstores enable. “Bookstores are a place where people go not just to find a new book, or an old book, but to have a fundamental conversation with themselves about who they are and who they aspire to be,” he says.

If you’re looking for a less existential way to find a good read, however, Mustich will be providing yet another option soon: He’s working on a book, due out in 2013, titled 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die.

Christopher Shea ’91 writes The Wall Street Journal’s Ideas Market blog and Week in Ideas column.

No responses yet