ON BOOKS: What Princeton students are reading

An undergrad’s search for the book of her generation

When I was 12, I was that sort of voracious reader who ran up against the public library’s 40-book borrowing limit every week. Reading meant one thing: disappearing into Green Gables or some post-nuclear society as soon as I got home and emerging only in time for dinner.

At Princeton, reading is more nuanced. You’ll most often find students “doing reading,” highlighting packets of printed-out chapters at a slightly uncomfortable pace. Reading for fun — the kind of reading that defined my life between grades five and 10 — is less common, and a lot more complicated.

Recently my editor came to me with a question: What books are students reading? In the 1970s, collegians learned about love from Love Story, took inspiration from Jonathan Livingston Seagull, and embarked on journalism careers after reading All the President’s Men. For a certain set of 1980s collegians, Bright Lights, Big City, Jay McInerney’s tale of being young and in New York, was practically required reading.

But in the search for the book of my generation — the tail end of the Millennials — I’ve struggled to find the one must-read on campus. And not only because I hadn’t picked up a non-assigned book since September. What made it really difficult was that I’m not alone.

“I want to know what the definition of ‘reading for fun’ is,” a friend says when I mention my assignment one night. We are sitting on the couches at Murray-Dodge Café, where you can pick up free cookies and tea after 10 p.m. It’s the perfect place to settle down with a good book, but most of the students are frantically “doing reading” instead. “Because I read articles every day,” she continues, “but I never commit to books, because I never know when I’ll be able to get back to them.”

“I read short stories and stuff,” another friend says. “I think that counts, even if it’s not a book.”

It’s not that my peers and I don’t read. We read all the time — essentially, whenever we’re on the computer. A recent study at the University of Arkansas found that students spent an average of just under an hour reading non-required online sources every day, but that sounds shockingly low to me.

Here’s how I read: My homepage is the website of The New York Times. I open my browser several times a day, and I read a few articles each time. I read screenplays, essays, and blogs about fashion, food, economics, technology, and journalism. I check my Facebook and Twitter feeds and my Tumblr dashboard multiple times a day. There I might find a link to a magazine feature about squid jigging (how you catch the slippery cephalopod), which will lead me to a Wikipedia article on giant squid, and eventually to a news article about thousands of Humboldt squid washing up on the beaches of San Clemente.

I do have several books I’d like to read. They’re sitting in a stack by my bed, waiting in vain for the campus WiFi to go down so that I finally might open them.

“Books have at least the illusion of commitment, in a way that articles don’t,” says Oren Lurie ’13. Opportunities for reading often come in 20- to 30-minute chunks — or, as Trayvon Braxton ’14 explains, “in between homework.”

Almost every Princeton student I spoke to professed a love for reading, typically with great enthusiasm and a tinge of nostalgia. But nearly as many also said that they read books for fun only during school breaks. A 2007 study by the National Endowment for the Arts found that 74 to 80 percent of college freshmen and seniors read four or fewer books on their own during the school year. In a 2010 survey of college librarians, nearly 70 percent reported that the largest barrier to recreational reading on their campuses was “too much reading for class.”

Reading for fun during the school year is “hard to justify” if you have work to do, one student tells me. On a campus obsessed with productivity, the idea of “justifying” books seems to come up often, even among those of us who spend hours on Facebook or the television site Hulu.

“The act of reading a novel for enjoyment’s sake is not a particularly useful act,” suggests Alex Meyer ’12. “It’s purely recreational, whereas reading a Facebook post or an article ... it’s reading, but as a tool for something else.”

“I know students read,” says Mathey College Director of Studies Kathleen Crown, who organizes the college’s book group, one of two residential-college book clubs on campus. “I’ve seen it happen.” The group, started by Elyse Graham ’07, offers free books during school breaks — when students might have a few hours to spare — to those who are willing to meet for a discussion afterward. “I think students are really scheduled, and they’re doing productive things all the time,” Crown says. “But it’s hard to schedule time for reading.”

A recent hit in the club was Bumped by Megan McCafferty, a “young-adult” take on Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novel The Handmaid’s Tale that attracted 25 to 30 readers, most of them female. Like me, many had read McCafferty’s best-selling series, which, from 2001 to 2009, followed New Jersey teenager Jessica Darling all the way to her mid-20s. Like the Harry Potter series, the writing grew older with the readers.

At Princeton, reading for fun, when it happens, is driven by several factors: interest, of course, but also — a little bit — the desire to keep up with the students around you when someone makes some erudite comment about Nabokov, or at least look like you could. “I’m not reading Proust because I want to know whether Swann’s romance works out,” one straight-talking senior tells me. “I’m reading it because it’s Proust, and it looks good on my coffee table.”

While we haven’t lost the desire to read, the cultural center of our generation has shifted away from books, toward social media, Hollywood, and TV, notes Justin Cahill ’11, an English major who works as an editorial assistant at W.W. Norton & Company. When books dominated the spread of ideas, what people were reading said something about them. Today, the relationship between books and the cultural zeitgeist is less clear because the book faces greater competition.

“We in publishing worry about that,” says Sandy Thatcher ’65, former editor-in-chief of the Princeton University Press, who continues to work for several academic publishers. “There have been studies that track generational reading habits, and there are some clear signs that it’s going to be tough times for the book-publishing world.”

The Internet has vastly expanded our cultural options, giving students in Princeton a chance to watch Al Jazeera or read The Guardian. Can contemporary fiction lure readers away from the thousands of options on Netflix and Hulu? Can anything compete with Zooborns.com and its photo galleries of baby cheetahs?

The feeds, streams, and dashboards that deliver customized content straight to our laptops and phones are convenient. But they also mean that we’re all living in our own media bubbles, formed by both taste and algorithms. So there seems to be no single book that bonds my generation in our college years — no book that’s being passed around the eating clubs and dining halls.

“These collective moments that we used to have, that Americans did as a culture — nowadays, those things don’t exist,” says Don Troop, who for the last seven years surveyed college bookstores for the “What They’re Reading on College Campuses” column in The Chronicle of Higher Education. Once in a while, he says, a book still comes along that everyone wants to read — like the Harry Potter books — “but those things are rarer and rarer.” The Chronicle feature fizzled out last spring, after tracking college students’ reading habits for four decades — a reflection both of the fragmented nature of our reading choices and of changes in the bookselling business (with shops closing, college stores increasingly serve nonstudents).

What do Princeton students read when they have time? There are a few perennial trends, because there’s no better place to read This Side of Paradise than in the window of a freshman dorm room. Books that have anything to do with Princeton, a genre that includes novels written by professors and alumni, will keep our interest long after we’ve graduated.

The classics are also top sellers. The cart of $4.95 paperback Oxford classics that sits in front of the Labyrinth bookstore on Nassau Street constantly is being restocked, as are the gem-toned hardcovers, says Virginia Harabin, the store’s general manager. Students often tell shop employees that the books are not required reading, but “just for me.” It’s not unusual to find Moby Dick or One Hundred Years of Solitude on dorm-room bookshelves.

“On campuses, all sorts of people talk about new music. You get ‘cred’ if you say, ‘Hey, I found this new band,’ and they turn out to be great,’” says Seth Fishman ’04, a literary agent. “That doesn’t happen with books in college.”

Instead, you start working on the canon — the books to read before you die, or even better, before you graduate — to be “an educated member of society,” as many students say. There’s a reluctance, several students tell me, to engage with books that aren’t tried and true. “You don’t know what will stand the test of time,” one senior explains. “It’s like, ‘Oh, man, I dedicated myself to reading the collected works of some author and two years later, everyone’s like, who?’ You don’t know who’s going to be the John Steinbeck or F. Scott Fitzgerald of our time.”

So unless it has been welcomed into the ranks of Established Good Literature, contemporary fiction is less popular on campus. Students I spoke with were reading books such as Middlesex, by Princeton creative writing professor Jeffrey Eugenides; American Pastoral, by Philip Roth; The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, by Junot Díaz. All Pulitzer Prize winners. While they’re not classics, they could be, someday. Eugenides’ newest novel, The Marriage Plot, a coming-of-age novel about three Ivy League students navigating love and post-grad life, might seem like bait for the Class of 2012. So I read it, in preparation for this article. But I could find only one other student who had done the same.

Other books that have found an audience here — and at other colleges — typically are aimed at teen readers, such as the Twilight series (about vampires, romance, and the high school prom) and the science-fiction drama The Hunger Games. “A piece of advice to would-be authors: If you want your books to appeal to the college crowd, aim low,” Troop wrote in the Chronicle in May.

“You’re more likely to hear a werewolf howl than Allen Ginsberg,” wrote Washington Post book critic Ron Charles in March 2009. “Here we have a generation of young adults away from home for the first time, free to enjoy the most experimental period of their lives, yet they’re choosing books like 13-year-old girls — or their parents. ... Where are the Germaine Greers, the Jerry Rubins, the Hunter Thompsons, the Richard Brautigans — those challenging, annoying, offensive, sometimes silly, always polemic authors whom young people used to adore to their parents’ dismay?” Critics of Charles’ thesis suggest that books topping the list in previous generations — starting with Love Story, the leading book in the Chronicle’s very first survey —– were not exactly intellectual tomes, either.

Popular “young-adult novels,” which typically feature teenage protagonists, are becoming grittier and more appetizing to the college palate, though they don’t offer the rebellious, change-your-life ideas for which Charles waxes nostalgic. As a result, the genre — once geared toward younger teens — has become more appealing to older readers, Fishman says.

There’s another, simpler reason busy college students read young-adult fiction: “It takes less thinking power,” says Maia ten Brink ’13. “And less time,” adds Stephanie Tam ’13.

The obvious candidate for the book of my generation is J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. Harry and his friends are of our cohort — we grew up with them. The books grew as we did, in size and complexity, from 309 pages to 784 pages, from funny-tasting jellybeans to the ultimate sacrifice.

College marks a transition between young adulthood and adulthood. The childhood left behind can be an intellectually fascinating thing, says English professor William Gleason, who teaches a wildly popular course on children’s literature. Of the 450 or so students who generally enroll (the number is capped), only a few have not read the Harry Potter series, he says. The last time the course was offered, in 2010, as many as 20 or 30 students who were not enrolled in the class also showed up for Gleason’s lectures on Harry Potter.

“When we got to Harry Potter [in precept], everyone was tripping over each other to talk about it,” says D.J. Judd ’12, who was enrolled in the course. “You don’t have to be an English major to know about the greater ramifications of Harry Potter ... because Harry Potter is us.”

By that, he means that our generation was J.K. Rowling’s target audience, the first to experience the phenomenon. My parents drove me to the bookstore at midnight four times so I could stand in line to get the latest Harry Potter book. Almost all my friends did that — and then came home and read for nine straight hours.

“Harry Potter was almost like a lifestyle,” Judd says. “There was a period of time where you think you are Harry Potter, when you’re 11.”

There’s no doubt students still love the series. When the final movie came out last summer, some dressed up in robes and threw a party in the Rockefeller College Common Room, taking full advantage of Princeton’s resemblance to Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. We love Harry Potter today not because of its coming-of-age themes or even because of the wonderful story. We love it because of how we felt when we were reading it, and how we were willing to read it under the covers with a flashlight if we had to.

“In college, particularly at a place like this, the ironies of your education and the demands that are placed on you — the need to read and read more and at a certain level — it makes people think about the days where they used to read for pleasure and not for academics,” Gleason says. And so the books and authors that we love today are often the ones we loved when we first discovered a passion for reading. When Gleason gives the students in his “American Bestsellers” course the chance to pick their final book assignment, they often pick a Harry Potter novel.

So perhaps Ron Charles had a point when he said that my generation chose our books like 13-year-old girls — he just didn’t understand why. At Princeton, we’re not all after the newest young-adult release in the teen section. College students are adult readers, Seth Fishman tells me, just ones who are catching up on our Dostoyevsky before jumping into the rest of the bookstore. And for now, we’ll return occasionally to the stories that we once loved, maybe as 13-year-old girls. It’s not the candy to required reading’s Brussels sprouts — it’s comfort food. As Bobbie Fishman, who manages the children’s section at Labyrinth, tells me, the college students who venture into her section are often there to visit “old friends.”

“I sometimes think we never escape the 13-year-old reader we were,” says author and creative writing professor Chang-rae Lee. “That’s when everything forms — passion, knowledge, a certain sense of aesthetic, direction, an affinity begins to form. And maybe it’s also the time when we’re most open.”

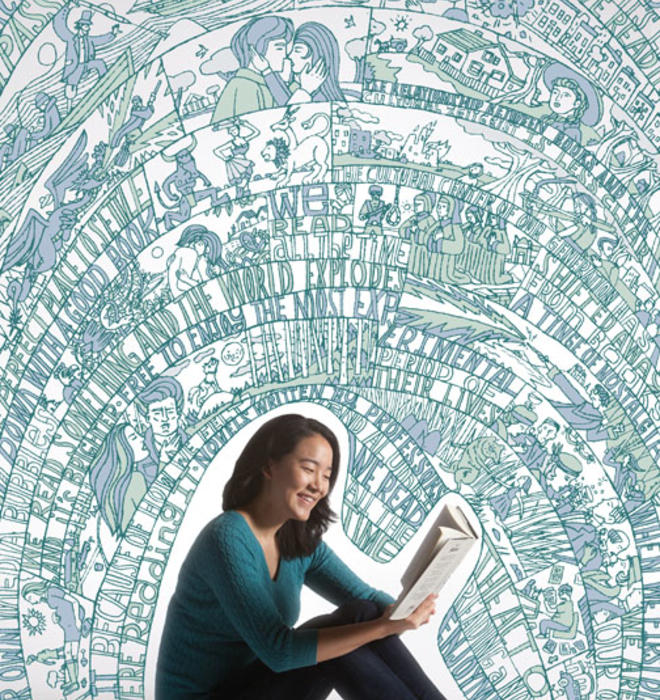

“We all have a primal moment of reading, where we read something and the world explodes, and it’s brighter and all that,” he says.

That is the moment to which students try to return, again and again. We can engage with current events and big ideas online. When it comes to literature, we love the books that remind us what it’s like to love reading.

Angela Wu ’12 is a PAW On the Campus columnist and a freelance journalist.

No responses yet