Hey, Brooke Shields ’87

You’ve spent your whole life in the public spotlight as a model, entertainer, and author. Tell us … Now what?

In early 2021, in the heart of the pandemic, Brooke Shields ’87 suffered a serious break to her femur, requiring multiple surgeries. Then came a potentially life-threatening staph infection. “It gave me a lot of time because I was in the hospital for a month by myself,” Shields says. “I thought, ‘If you die, what will you not have done?’”

Shields, the world-famous model and movie star who studied Romance languages and literatures at Princeton, had accomplished more in her first 18 years than most people do in a lifetime. But lying in that hospital bed, she cycled through how much more she wanted to do.

The list included an online community for women over 40 called Beginning is Now, which she launched later that year. Meanwhile she’s working on a possible beauty brand. She’s also continued to act and perform while writing a new book that redefines the experience of aging. And this year she raised her first round of financing for a new company.

“Starting your own business is a marathon,” she tells PAW. “So many of the things I’ve done have been versions of sprints, like jumping into a show you have to learn in nine days. This is taking patience and endurance.”

Last year, she launched a podcast called Now What? about what people do when life doesn’t go according to plan. It seems like a surprisingly democratic choice for someone who’s floated among the glitterati since before she could drive. But many actors are turning to the medium, both for its creative freedom and the chance to connect directly with audiences.

“I’m fascinated in how people decide to continually pivot,” says Shields. “We [can] get so stuck in what we want [our life] to be, or what we think it should be, or what it has been in

the past.”

Shields knows from pivots. After shooting to fame as a child, she made the unusual decision to slow her career to go to college — and then faced crickets. She eventually found her way back into entertainment via Broadway, followed by a hit TV show that earned her two Golden Globe nominations. She’s since written two memoirs (and two children’s books), while continuing to work as a model and spokesperson, and more recently plunging into Netflix rom-coms. “I often look at my life as a kaleidoscope where all these perfect pieces fit, and then you shift it just a little bit, and it’s chaos. Then you have to either stay settled in that chaos, or shift it just a little bit more, and a new pattern arises.”

Shields, 58, started Beginning is Now, whose conversations take place on Facebook and Instagram, after reaching midlife and noticing how the broader culture starts ignoring women right at the point they’re finally becoming comfortable with themselves. “Nobody talks to us,” she says. “Nobody markets to us. Nobody says you can be sexy. Nobody says you can try new things. Nobody says you don’t have to give a shit anymore.”

This year has been a turning point for Shields. While she’s never been out of the public eye, Hulu released a documentary in April that has propelled her back to the forefront of the national consciousness. Pretty Baby: Brooke Shields examines the media’s sexualization of girls and young women through the lens of Shields’ early life — and in doing so invites viewers to rethink their conception of who she is and how their ideas got cemented.

In the ’70s and ’80s, Shields sat at the top of the cultural pantheon. (Think: covers of Vogue, box office smashes like The Blue Lagoon, and the notorious Calvin Klein ads.) But it came at a price: Shields was frequently attacked for projecting an overly sexualized image of teenage girlhood. The Hulu documentary unpacks the behind-the-scenes dynamics at work in that era, when the women’s liberation movement had turned its back on conventional notions of femininity, and in response, the advertising industry turned to ever-younger models. When the public didn’t like what they saw, it was the girls who were attacked, not the photographers and filmmakers using them as canvases for their own ideals.

“There was this pivot toward young girls to sell lip gloss and Calvin Klein jeans, and nobody said, ‘Wait a second, this is not OK,’” says Ali Wentworth, producer of the documentary, which takes its title from the 1978 film of the same name. Director Louis Malle cast the 11-year-old Shields as a child prostitute in early 20th century New Orleans. The film was based on a true story, but its subject matter generated intense controversy — and put Shields and her mother in the hot seat for taking the role in the first place.

The podcast Now What? offers a more expansive view of Shields as well, even from the person the public has come to know in the decades since. The voice in your earbuds isn’t the poised beauty icon, or the genial talk-show guest, or the goofy comedian. Instead, it’s a warm, curious, and deep-hearted interviewer, with a wry sense of humor and a down-to-earth fearlessness about exploring the most wrenching of topics. Whether she’s talking with Good Wife actor Julianna Margulies about the challenges of growing up under a deeply flawed parent, or with Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt star (and former Princeton Quipfire! improviser) Ellie Kemper ’02 about both Wawa runs and the pain of professional rejection, it feels like a curtain is being pulled back, and we’re finally getting a glimpse of the real Shields, in all her complexity and colors.

“I just interviewed [singer-songwriter] Sara Bareilles, and she practically brought me to tears because she talked about doing the things that scare you and realizing where your limitations are, but [not making] them who you are,” says Shields. “She talks about finding your voice and what that means to all of us differently.”

Before she came to Princeton, the teenage Shields rarely felt she could have a voice of her own. Social media didn’t exist yet, and the journalists and talk-show hosts who interviewed her struck her as more interested in advancing prevailing narratives than hearing what she actually thought. In one such interview, when she was about 12, “I say to this woman, after she’s asked the same question four times, just slightly changing the words” — about whether Shields thought Malle’s Pretty Baby had robbed her of her childhood (she didn’t) — “and I’m trying not to be rude — I say, ‘Excuse me, ma’am, but I don’t think you want my answer.’”

On sets, Shields remained focused on delivering what was asked. “The pride I derived from my job stemmed primarily from being liked and accepted,” she wrote in her 2014 memoir, There Was a Little Girl. Princeton, though, marked a turning point. It wasn’t so much a life-changing experience, Shields emphasizes, as a life-revealing one. Her experience on campus helped her tap back into herself — her own ideas and sensibilities. “I needed to reveal myself to myself,” she says. “I needed to learn that I could have an opinion.”

When shields moved into Mathey College in the fall of 1983, she was probably the most famous freshman the school had ever seen. Taking time out to go to college wasn’t typical of young celebrities, but it’d always been part of Shields’ plan. Both her parents cared deeply about education: Teri Shields, who hoped for more for her daughter than she’d had from her own working class upbringing in Newark, and Frank Shields, a University of Pennsylvania graduate from New York’s Upper East Side. When a brief marriage ended in divorce, Teri waived alimony, asking only that Frank, a business executive, pay for their daughter’s schooling.

Shields, for her part, wanted time away from the fickle worlds of modeling and acting, where she knew her worth was often based on arbitrary qualities, like her much lauded beauty. “I remember thinking, ‘This will be the one thing that can’t be taken away from you,’” she told Minnie Driver on that actor’s podcast.

With plans to stay close to home and dreams of ivy-covered Gothic buildings, Shields fell in love with Princeton during a fall football game. “The atmosphere made me giddy,” she wrote in Little Girl. “I could feel an excitement for knowledge … . I was so comfortable with these people [who] were extraordinarily genuine and smart, but not affected.”

Soon after matriculating, however, Shields was consumed with loneliness. “People tried to be so nice. They just tried to give me my space. And I was like, ‘I don’t want space … . I want friends,’” Shields recalls in the documentary.

An elitist skepticism was probably also at work. After women’s lib, serious women were no longer supposed to be interested in makeup and fashion — the very things Shields symbolized. A woman from the Class of 1973, Princeton’s first fully coed cohort, wrote a scathing letter to PAW. “Who, one wonders, is the talented and intellectually superior student who has not been admitted to Princeton this year so that Brooke Shields might be?” It seemed doubtful, the letter continued, that Shields’ “film and modeling experience” would be “likely to enrich campus life.” (Several other alumni wrote in later, challenging those assumptions and defending Shields’ right to attend.)

What her classmates may not have realized was that Shields actually had a lot in common with them. Studio 54 snaps notwithstanding, Teri, with whom Shields lived most of the time, had always insisted her daughter lead a normal life. Resisting the lure of Hollywood, Teri kept them in the New York area and sent her daughter to regular schools, including Dwight-Englewood School in New Jersey. Work was mostly restricted to after classes and weekends and vacations. Shields routinely spent time with her father’s second family, first in Manhattan and then on Long Island, including her five step- and half-siblings. “All of those things that were associated with being these sexy personas just didn’t feel like who I really was,” Shields says in the documentary. “The nerdy, kind of dorky person who was creative and intelligent was at the core of who I was.”

Working in fashion and films, Shields had developed a strong work ethic to balance it all with school. James W. Wickenden Jr. ’61, Princeton’s director of admission from 1978 to 1983, later said Shields’ academic qualifications were never in doubt. The admissions committee mostly worried that such a successful actor and model wouldn’t stick it out all four years and wouldn’t participate in campus life. A conversation with Shields convinced Wickenden her interest was genuine.

Still, the loneliness that freshman fall nearly knocked her off course. Shields went home every weekend and soon started talking about dropping out. Teri convinced her to stay, insisting that “if I quit, I would never, ever forgive myself,” Shields wrote in Little Girl. And Teri was right. When Shields keynoted Class Day in 2011 (wearing her 1987 beer jacket), she told the assembled seniors, “I graduated more confident and more proud of myself than I had ever been … . Without the four years of learning and growth that culminated in my degree, I would have never survived my industry, a business that predicates itself on eating its young. I would have become a cliché. I never would have been able to adapt or reinvent.”

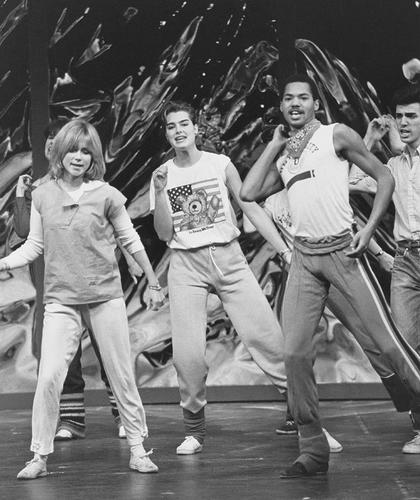

On an early episode of now what?, Shields shared with Wentworth that one of her earliest “now what” moments was trying out for Princeton’s eXpressions dance company her freshman year — and not making it. “It was so embarrassing … to really put myself out there and not be good enough,” she said. “I just thought, maybe it’s true, maybe I’m not good.” The following summer, Shields threw herself into dance classes in Manhattan, and the next year, she made the troupe. “Those were the things that were the most revelatory for me,” she tells PAW. “It’s not that it always works out. But it’s that you have to put the work in and see where that takes you.”

Shields was most known on campus for performing with Triangle Club. “Triangle was this unbelievably safe, nonjudgmental environment where I could grow, and be challenged, and know what it feels like to be a part of a team,” she says. The close-knit community also gave her the freedom to experience the social aspects of college life. “They were protecting me,” Shields says. “No one was going to write about it or secretly photograph me and release it to Page Six.”

Since Princeton didn’t have a film studies department, Shields chose to major in Romance languages and literatures, with a concentration in French. One day junior year, one of her professors, Karl Uitti, called her into his office. “He saw me not trusting any of my instincts, or my opinions, and waiting and watching to see what other people said,” Shields says. “He wanted to stop that and say, ‘No, you actually have opinions. So why don’t you just allow yourself to have them and see what happens?’”

It was a defining moment for Shields, who credited Uitti in her senior thesis for “helping me to have faith in my own hypotheses.”

“He had seen this very hardworking person who wanted to do better and keep growing,” Shields says. “He seemed to just ask more of me.”

In her thesis, Shields examined two of Malle’s films through a literary lens, in part to reclaim the meaning and artistry of Pretty Baby from the desecration it had received at the hands of American critics. (“I think it’s possibly the only really beautiful film I’ve ever been in,” she told an interviewer this year.)

Shields was particularly interested in the theme of lost innocence, and she analyzed how Malle was using film not strictly as entertainment but more as an artistic medium to provoke contemplation. Screenwriter Polly Platt had written Pretty Baby as an allegory for what she was seeing in 1970s Hollywood. “Malle holds a mirror to society and asks us all to take a good look,” Shields wrote. “He wants to shake [the audience] out of complacency and force them to re-evaluate certain conventionally accepted attitudes.”

After graduation, Shields lost her footing in the film industry. “I had no idea that going away from the Hollywood game for years while getting an education would have such a negative effect,” she wrote in Little Girl. She struggled to find her way back. In 1994, she was tapped to play Rizzo in a Broadway revival of Grease. Two years later, a guest spot on Friends as Joey’s demented stalker put her comedic chops on display. Then she got her own sitcom, Suddenly Susan. “I used to think that I would only be credible if I went to those dark places and was a ‘thespian,’” Shields told Kemper on Now What? “And then I got older, and I [realized] I don’t enjoy it. I only enjoy comedy.” (“Music to my ears,” replied Kemper, who performed with the Upright Citizens Brigade before snagging her breakout role on The Office.)

Shields says her memoirs are among her proudest accomplishments, including 2005’s Down Came the Rain, about her postpartum depression and her path to recovery with help from therapy and medication. An agent suggested she write about her experiences, given how little the condition was understood at the time, but Shields hesitated, dubious that people would want to hear about the struggles of a celebrity. During her first year at Princeton, a publishing house had approached her about doing a book on college life for young women, only revealing after the contract was signed that they wanted to use a ghostwriter. Instead of going deep, On Your Own ended up being “a very silly book with short sentences about important things like the versatility of leg warmers,” Shields wrote in Little Girl.

Shields insisted on writing Down Came the Rain herself. The book received rave reviews and was widely praised for raising awareness about a much-overlooked condition. “Had I not gone to Princeton, I wouldn’t have been able to pitch a book and make it to The New York Times bestsellers list,” she tells PAW. “You have to be taught how to think, how to write, how to see what you think.” The concepts she learned in her college psychology classes, along with her own experiences in therapy, “allowed me to have authentic views of my experience and myself and get them down on paper.”

Shields’ ceramics instructor, the celebrated Toshiko Takaezu, also planted seeds that influenced her writing. “She taught me to get out of my comfort zone and stop trying to be perfect,” Shields says. Sitting at her pottery wheel, Shields would try to force her clay into perfect shapes. Takaezu would walk by and knock them over. “That’s not how the flow of any artistic endeavor works,” Shields recalls Takaezu saying. “The tighter you hold, the less you are free.” Takaezu’s guidance, Shields says, “allowed me to write a book about postpartum depression and not be overly maudlin or, ‘poor me.’” (Shields keeps a pot she made with Takaezu on the landing of her New York home.)

Unexpectedly, after the book came out, the actor Tom Cruise took a swing at it. A member of the Church of Scientology, which looks askance on psychotherapy and medication, Cruise attacked Shields as “dangerous” and accused her of spreading “irresponsible misinformation.” Shields stood up for herself with a New York Times opinion piece dismantling Cruise’s claims and arguing his comments were “a disservice to mothers everywhere.” Cruise eventually backed down and apologized.

“She goes a thousand percent,” Wentworth says. “That is part of how she has remained sane and sustained a career and a life. You can knock Brooke down, and she will get back up. There’s no lying under her duvet and feeling sorry for herself.”

The hulu documentary came about as a result of conversations Wentworth and Shields had about her early work experiences. “The documentary was a huge act of trust on my part because I hadn’t, maybe ever, not been reduced to whatever the lowest common denominator was,” says Shields, who had no say over the final cut. Others had previously approached her about doing a project on her life, but “it was always thin,” Shields says. Lana Wilson, the film’s director, who also helmed the Taylor Swift documentary Miss Americana (and who received an Emmy nod for her direction of Pretty Baby: Brooke Shields), suggested something more ambitious. “I wanted it to be about a bigger topic,” Shields says. “This ignites other conversations.”

And ignite it has. Shields has made the rounds this year of morning shows, podcasts, magazine articles, and even a long interview in The New Yorker. Since the #MeToo movement, audiences seem open to recontextualizing what was happening to young models and actors in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s in general, and in Shields’ life in particular. “What happened to [Shields], and the way people talked about her, and the perception of her, isn’t really about her as an individual,” BuzzFeed culture writer Scaachi Koul says in the documentary. “It’s just about women.”

The film also allowed Shields to take stock of herself. “I’ve never seen my whole life all together. I just lived it,” she says. “And seeing it all together, I was proud of how I came through it.” It also created an opening to break from the persona cast in the public eye years ago and fully own her identity. “This is a level of my voice I’ve been wanting to inhabit,” she says.

This fall, Shields screwed up her courage to create a solo performance of stories and songs at New York’s famous Café Carlyle. “It’s not what I do,” she says, but “whenever there’s something that scares me, I have to do it.” A week later, she was on stage at the Irish Rep, starring in Love Letters opposite Mad Men’s John Slattery.

When asked what she wants to see in her next few decades, Shields talks about her two daughters, acting, and her mission to bring the lives of midlife women out of the shadows. “Career-wise, I just hope I’m still working. I’ll play the Maggie Smith roles. I’ll learn how to roll a wheelchair if I need to,” she jokes.

She’s also gamely embracing new avenues for sharing parts of herself on her own terms. During the COVID lockdown, Shields partnered with her trainer to broadcast workouts on Instagram — unself-consciously fumbling with her phone to figure out how to split the screen. After her older daughter left for college, Shields shared her grief on TikTok, tears and all. And when Jordache tapped her for a jeans campaign last year, including a photo featuring her bare back, she had one requirement: No retouching. “It was important for you to see this is my 56-year-old body,” she told People magazine. “There is something about owning your sexuality at this age that is on point for where we are today.”

“She finally understands her worth and her power,” Wentworth says. “Now is not the time she wants to be shushed or told, ‘Your time is up.’ She’s just finding her voice.”

E.B. Boyd ’89 is currently working on a book about women entrepreneurs.

2 Responses

Martin Schell ’74

1 Year AgoPersonal or Promotional?

E.B. Boyd ’89 deserves praise for quoting a wide variety of sources in her interview of Brooke Shields ’87 (“Now What?,” November issue). And Ms. Shields certainly has shown courage in maturing beyond the limited image that was marketed by her mother, various agents, etc.

But to paraphrase the question Ms. Boyd quotes at the end of her first paragraph: “If you write this article, what will you not have done?” One answer: Name the interviewee’s children and their father. In contrast, “self” appears 18 times in the article.

Another answer: Describe the downside of Teri’s aggressive promotion that was noted in the press at the time, but now merits only a passing “deeply flawed parent” comment amidst several plaudits about her that seem like airbrushed nostalgia.

Admirable as the alumna’s dedication to her new direction is, I can’t avoid the feeling that this is a promotional interview intended as a repackaging of celebrity status.

George Angell ’76

1 Year AgoAn Idea for Brooke Shields

PAW asks, “What now?” concerning Brooke Shields ’87 and the new ways she can put her creative gifts, ambitions, and generosity to work. May I make a suggestion, with the Princeton community in mind?

Now and then, we everyday mortals have a random encounter, out of the blue, with famous people. In all likelihood it has happened to you, maybe at a restaurant or ballpark, maybe in a hotel elevator. If so, you know that the experience can be awkward and, if a verbal exchange is called for, positively unnerving. Face to face with the celeb, we turn into tongue-tied dopes. All the more so if the person is one of those supernovas of talent and glamor who have become icons of the culture. I’m no stranger to the phenomenon of brain freeze in the presence of a demigod adored by millions. In my case, Ms. Shields did the honors.

Ten years after graduating, I returned to Princeton for a few months on the dime of my employer to do specialized research. It was fall term of Ms. Shields’ senior year at Princeton, 1986-87. The semester zipped by, Christmas came and went, and I had caught only fleeting glimpses of the University’s most gawked-at undergraduate around campus. That changed on a morning of leaden skies and heavy snow in late January, a few days before my wife and I would be wrapping up our stay and returning to our rowhouse in Baltimore with our son, not quite 2 years old.

It was my habit to take my reading materials to an elegant but cozy reading room on the third floor of Firestone Library, which for some reason was lightly used by students. The walls were lined with original paintings by Frederic Remington. A library employee sat at a desk watching over the place. On this morning, however, I found the door to the reading room closed and locked. Figuring that the blizzard outside had probably stalled the arrival of the attendant with the keys, I stood in the deserted hallway considering where else to park myself and my texts. As I weighed my options, I heard a woman’s voice behind me. “Excuse me,” she said, ”when will the reading room open?” I looked around and beheld a tall, slim young woman, no less drop-dead beautiful for being casually dressed. She was instantly recognizable. There was no way to play dumb and act like I thought she was speaking to someone else — we were alone in the hallway. The question had been put to me. By Brooke Shields!

If you have ever been driving on a busy highway in late afternoon and suddenly found your vision obliterated by the setting sun dead ahead as your vehicle barrels forward, you know how I felt as I looked blankly at Ms. Shields, my mental faculties blinded. “Keep your cool,” an inner voice told me, but it was a panicked voice. I was worse than addled. My intellect was stripped away as unceremoniously as a straw hat on a blowy beach. All I had left was the baseline cognitive capacity to answer her question by sheepishly grinning and then mechanically reading out the room’s hours of operation printed in big black letters on the door, as though she couldn’t read them for herself. It wasn’t a conversation starter. She surmised that I was not, as she had mistakenly thought, a library employee — or even someone with a lick of sense — and she said nothing more. She turned to go elsewhere, but just as she did, the actual attendant came rushing up, shaking snow from his hair and apologizing for his tardiness. His frozen fingers futzed with his key ring, and he opened the door. Ms. Shields, all business, went in and sat down to study. I followed and took a spot on the far side of the room, feeling arch-foolish but no longer hyperventilating.

Students on Ivy League campuses are much more subject to this kind of impromptu brush with fame than the average person. Princeton attracts the leading lights of the arts, politics, science, sports, medicine, commerce, and any other endeavor you can name, some as faculty members, some as visitors, and a few even as fellow students. You may bump into one when you least expect it, around any corner, like the time, as an undergraduate, I quite literally ran into Golda Meir in a campus doorway.

Ms. Shields would be doing a great service if she set aside one day every fall, preferably during the freshman orientation period, to meet with the incoming class and hold a sort of tutorial on the subject of everyday people’s interactions with VIPs. She could impart her well-earned insights and also answer the freshmen’s questions, drawing them out and trying to put them at ease. Besides explaining some do’s and don’ts, she could help give students a sense of how these encounters play out from the perspective of the celebrities themselves and how they, too, have their anxieties, inadequacies, and discomfort to contend with. After all, they have to handle these situations all the time, not just on rare occasions like the rest of us.

As a postscript, I should report that my wits did rally on that snowy morning in 1987, at least to the point that, after settling into my seat in the reading room and staying put for a decent two or three minutes, I had the gumption to head down to the lobby and call my wife on the pay phone. Ann had been a bit disappointed never to have laid eyes on Ms. Shields during our months in town. Now I knew exactly where she could find her. Duly tipped off, Ann bundled herself and our toddler up and gamely pulled him in his Radio Flyer red wagon through the driving snow all the way to Firestone — a good long trek from our rental down Prospect Street. I met her in the lobby, took our son in my arms, and sent her up to the reading room. Entering quietly, she had no trouble spotting Ms. Shields, still the only person in the room other than the attendant. Ann slowly strolled around the room’s perimeter, sneaking glances at the object of her visit between leisurely inspections of the Remington paintings. When she was halfway around, the attendant got up and approached her. “Can I help you with something?” he asked. “No thanks,” she said. “I’m just looking at the paintings.” “Yeah, right,” said he.