JEREMY NOBEL ’77 — PHYSICIAN, POET, public-health crusader — is scrolling through his phone, hunting for the snapshot he took a few days earlier: New York’s Washington Square Park at night, its famous arch bathed in floodlights whose reflected glow illuminates the intersecting paths below.

The photo’s meaning came to him only later, he says. “When I took this, I didn’t see the crossroads,” Nobel tells me, as we gaze at his screen together. “Because I wasn’t saying, ‘Oh, I’m at a crossroads in my life.’ It wasn’t that. It was, like, ‘Wow, there’s a kind of pretty Arc de Triomphe in the light.’ But the crossroads were there.”Did he perceive them subliminally? “Who the hell knows?” Nobel says cheerfully.

The moment encapsulates Nobel’s vision of how artistic expression can help heal the aching loneliness of modern life: first, by directing focused attention to a moment of experience; next, by encouraging further reflection on the meaning of that experience; and finally, by forging new human connections as you share that meaning with another person.

Nobel, 64, a board-certified internist and preventive-medicine specialist who teaches at Harvard’s Medical School and School of Public Health, is best-known as a pioneer in the development of electronic medical records. But in the wake of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, he rediscovered artistic passions that had lain dormant since his student days and turned his attention to the role the arts can play in combating trauma and loss.

Today, however, the Foundation for Art and Healing, which Nobel launched 14 years ago, has a new focus — the UnLonely Project. It’s an effort to address a less visible and dramatic public-health crisis: the widespread loneliness that characterizes our technologically intertwined, yet curiously isolating, cultural moment. The UnLonely Project’s targets include college campuses like Princeton, where a design class is spending the semester devising ways to decrease students’ loneliness.

“More people on the planet than ever before, more digitally connected than ever before, lonelier than ever before,” Nobel says. “What’s going on?”

SOCIAL ISOLATION IS A CONDITION that can be quantified — this many friends, that much daily interaction. Loneliness, by contrast, is inherently subjective, the perception of a gap between the social connections you want and those you actually have. One person’s desolate solitude may be another’s blissful peace and quiet.

Yet these subjective perceptions of social connectedness can have concrete impact, suggests research by Julianne Holt-Lunstad, a professor at Brigham Young University, who in 2010 published a trailblazing study about the links between social connectivity and morbidity. Both social isolation and loneliness increase the risk of premature death from illnesses like cancer and heart disease by nearly 30 percent, a greater mortality risk than obesity, Holt-Lunstad has found. Combine those two factors with a third — living alone — and the increased mortality risk is even greater, the equivalent of smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

“Loneliness won’t just make you miserable,” Nobel says. “It will kill you.”

Loneliness wreaks its havoc through both biological and behavioral pathways. It can trigger a fight-or-flight response and depress immune functioning. People with more supportive social networks have lower blood pressure for their age than those who are more isolated, Holt-Lunstad has found, while a difficult relationship can bring on blood-pressure spikes. Over time, the cumulative impact of such stressors can make the development of disease more likely, she says.

Loneliness and social isolation can also modify behavior, Holt-Lunstad notes, by depriving us of connections that stimulate healthy choices. A parent tells a child to eat her vegetables; spouses remind each other to take their medications. “Having others around can have very powerful effects on health-related behaviors,” Holt-Lunstad says. “There’s so many ways in which relationships can influence us.”

Is loneliness increasing? It’s hard to be sure. But some telling demographic indicators suggest chronic loneliness may be on the rise, Holt-Lunstad says: More Americans are living alone, and fewer participate in religious, social, or civic groups. A recent survey by the health insurer Cigna, based on the UCLA Loneliness Scale, a commonly used research tool, concluded that 54 percent of American adults are lonely — up from 30 or 35 percent on past surveys, Nobel says.

If loneliness is up, there’s no shortage of speculation about the reasons why. Nobel points to an increase in factors that logically seem correlated with loneliness: the geographical mobility of young people, which frays extended family ties; the fragmentation and political polarization of American life; and the proliferation of digital technologies that chain us to personal screens, where social media shows all our friends happily partying without us.

For some struggling Princeton undergraduates, “there’s a little bit of a lament as they are taking an inventory of their social networks,” says John Kolligian Jr., executive director of Princeton University Health Services. “They seem sometimes flummoxed that they have lots of contacts, there’s lots of people who are in their life, who are writing to them and texting them, lots of friends being friended on Facebook, but that, somehow, something else is not happening.”

It’s not just the superficial, arms-length nature of relationships fostered on social media that can promote loneliness, Nobel says; it’s also the self-alienation that comes from striving to present ourselves as click-worthy brands.

“As more and more of your public persona isn’t who you are, you’re clearly going to have some challenges in relating to who you are,” Nobel says. “And if you can’t relate to who you are, you can’t connect with other people.”

IN HIS FIRST SEMESTER AT PRINCETON, Jeremy Nobel was lonely. In retrospect, his emotions seem routine, even banal, “except people rarely talked directly about it,” he says now. “I felt an enormous opportunity, but also a kind of risk that I wouldn’t perform to that opportunity. I felt nervous about exposing myself to other people on an authentic level — afraid of rejection, afraid of abandonment.”

It got better. He did well academically and enjoyed his membership on the fencing team. Although he was majoring in chemistry, he found himself drawn to the arts: poetry, which he had begun writing in high school, and photography, which he discovered in a Princeton course. After two years at the University, he decided to take time off to study with a photographer in Kentucky, but on the way to Louisville, he was seriously injured in a car accident.

“My life was saved by a very skilled general surgeon in a community hospital outside of Cincinnati,” Nobel says. “As I was recovering in that hospital, I just was so interested in the fact that somebody had this skill, this toolkit, that saved my life.” After a year of recuperation at home in Pittsburgh, Nobel finished his Princeton degree and continued on to medical school. He worked in primary-care practice, academia, and the corporate world; earned a public-health degree; and helped to develop some of the earliest electronic medical records and other digital health technologies.

“For 20 years or so, literature, humanism, and the arts were not a big part of my life,” Nobel says. “I still enjoyed the arts, but I wasn’t a maker of art. What changed? 9/11 changed.”

The national trauma reconnected Nobel with his own creative drive. From Boston, he watched as child psychologists armed with the tools of art therapy fanned out across New York City to counsel children traumatized by the attacks.

“The kids got better, and what got my attention was they got better across race and class,” Nobel says. “It wasn’t a cultural effect, so something had to be going on neurophysiologically. Something goes on in the brain when you are purposely looking and trying to pattern-match and think symbolically and non-literally about thoughts and feelings and experiences. I thought that was too important to not pay more attention to.”

To build on this insight, Nobel established the Foundation for Art and Healing, aiming to use the arts to help a variety of sufferers: traumatized children, patients living with chronic illness, veterans returning from Afghanistan and Iraq. The foundation worked with survivors of national traumas like Hurricane Sandy. And it promoted another idea: that creative expression could enhance the life and health of anyone, not just the troubled and the sick.

As the foundation evaluated the impact of its work, participants repeatedly noted that arts-based interventions decreased their feelings of loneliness and enhanced their sense of connectedness. In response, Nobel’s foundation refocused its mission, launching the UnLonely Project in May 2016. The project aims to raise awareness about loneliness and its health effects, reduce the stigma surrounding the condition, and connect the lonely, or those at risk of loneliness, to programming and resources. Its efforts focus on three sites of vulnerability: among older adults and their caregivers; on college campuses; and in workplaces, where the loneliness that workers experience in their personal lives can spill over into their professional ones.

So far, the UnLonely Project has begun collaborations with employers, universities, and social-service agencies, and sponsored two festivals of original short films. Princeton is exploring its own collaboration with Nobel, says Kolligian, the University Health Services director.

Nobel’s efforts “are allowing people not just to talk about the positive side, like the sense of belonging, but the negative side, too, the pain and suffering that goes along with excessive loneliness and disconnection,” says Joseph Behen, executive director of the Wellness Center at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, which is working with the foundation. “It’s a huge service.”

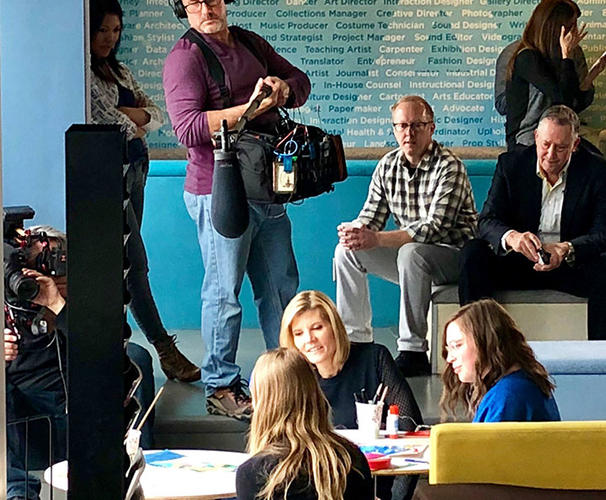

COLORED CONSTRUCTION PAPER, markers, and decorative stickers spilled over the conference table. Inside a Manhattan office, Nobel and a consultant facilitator were giving representatives from two Long Island community centers a hands-on demonstration of what the UnLonely Project calls a “creativity circle” — a support-group meeting centered on an arts-related activity.

Early next year, the community centers plan to run six-week programs of creativity circles targeting caregivers for the elderly and the sick. But on this crisp morning in early fall, social workers and managers bent over their own papers, creating squares for a group quilt. In one quadrant of their squares, participants represented their strengths; in the other three, they portrayed their support systems, the activities they rely on to decompress, and their hopes for the future. Some stuck to words. Others accessorized with stickers. One person drew trees and flowers.

It was interesting, one participant remarked, how the construction-paper square formed a unified picture of the resources available, creating a whole whose outlines might not have emerged in conversation. Nobel nodded. “Sometimes you can see the relationships between things differently if they’re laid out as made objects,” he said.

As the exercise wound down, people swapped stories about grade-school teachers who had shamed them out of making art. “I’m so not creative,” one woman said, describing her initial reaction to the quilt-square assignment. “I was so worried.”

Although Nobel is a serious artist himself — he is working on a book of poems, as he pursues a master’s degree in creative writing — the UnLonely Project’s programming is designed for everyone, not only those with talent. “We all have creative possibilities and potentials,” says Behen. “It’s a matter of engaging them and trying to realize them.”

THIS FALL, AS THEY DO EVERY YEAR, the Princeton students in Engineering 200: Creativity, Innovation, and Design broke into teams to devise solutions to a complex social problem. This year’s problem: mitigating loneliness at Princeton.

Research shows that 18- to 22-year-olds are lonelier than any other demographic group, and the American College Health Association’s annual surveys of college students suggest they may be getting lonelier. Nine years ago, 57.7 percent of those the ACHA surveyed reported feeling very lonely sometime within the previous year; by the spring of 2017, that number had risen to 62.2 percent.

Over the years, in response to the same survey question, Princeton students have reported higher-than-average rates of loneliness — over 70 percent in 2017, in line with results at similar elite institutions, says Sonya Satinsky, Princeton’s director of health promotion and prevention services.

Engineering 200 instructor Sheila Pontis says she chose the topic of this year’s project after four years of office-hour visits from students weeping over academic pressure, family expectations, or romantic disappointments. “They’re a sad bunch,” says Pontis, a lecturer in the Keller Center for Innovation in Engineering Education, who heads a design consultancy. “They feel like they can’t generally say how they feel. They just feel like they are alone, because there’s this kind of political response — ‘How are you?’ ‘Everything’s fine’ — when actually the students know that they’re not fine.”

It’s a phenomenon that Rachel Yee ’19, president of the Undergraduate Student Government, knows well: In her first year at Princeton, Yee says, she led an active social life but had no one with whom to discuss her increasingly troubling family problems. “I didn’t recognize that as loneliness,” says Yee, who has made mental-health issues a cornerstone of her student-government agenda. “I was, like, ‘How could I be lonely if I’m constantly with people?’ That was very confusing to me.”

Beyond the shared pressures of contemporary life, Princeton students face some issues unique to this campus, students say. The process of bickering for the selective eating clubs can ignite anxiety and stoke fears of exclusion; navigating campus life as an independent, without a dining-hall affiliation, can leave students feeling socially unmoored.

And achievement pressures are sometimes suffocating, says Sarah Sakha ’18, who co-chaired the Mental Health Initiative during her University career. “We isolate ourselves based on the fact that we are meant to always be working or be busy,” Sakha says. “Because of the culture of go-go-go, you often just feel alone in your struggles, and you feel that you can’t share them.”

A recent five-year, $5 million gift to Princeton, the Elcan Family Fund for Wellness Innovation, will be used to promote students’ well-being, resilience, and social connectedness, in part by expanding the visibility and reach of campus mental-health services, Kolligian said. Meanwhile, Yee is trying to break down the stigma associated with admitting vulnerability.

“It is perfectly normal not to feel 100 percent comfortable,” she reassured first-year students in an email sent out ahead of Lawnparties. “I remember knowing only a small handful of people and feeling a little lonely at times.”

Loneliness as a public-health issue transcends a single community, a single campus, even a single country: This year, Britain appointed ministers for loneliness and suicide prevention, becoming the first nation to elevate the issue to a matter of government concern. Holt-Lunstad, the Brigham Young researcher, who serves on the British government’s technical advisory group on loneliness, believes the United States needs national guidelines on social connectedness, comparable to those for nutrition and exercise.

“Just as we take our diet and exercise seriously for our health, we need to take our social relationships seriously for our health,” she says. “Everyone knows that they should be eating fruits and vegetables and what the standard is, and they know where they are in comparison. They may not be doing it, but they at least know.”

Nobel feels a sense of urgency about the work: He figures he has perhaps 18 months to create momentum around an anti-loneliness crusade before exhausting the public’s short attention span.

Still, he has no illusions about the likelihood — even, perhaps, the desirability — of entirely eliminating loneliness. “There’s some part of loneliness that probably is tied in to human experience,” Nobel says. “I don’t think it’s part of a healthy, normal psyche to not have some degree of loneliness. So get to know it — make friends.”

Deborah Yaffe is a freelance writer based in Princeton Junction, N.J.

1 Response

Jana Wardian

7 Years AgoTogether We Are Not Alone

I am working with our local JDRF to address depression for people with Type 1 Diabetes. We are simply conducting a series of workshops under the “Together We Are Not Alone” umbrella to connect us to one another. Such a simple intervention.