Aaron Burr Jr. 1772 may have killed Alexander Hamilton in their celebrated 1804 duel, but the shot was no less fatal to Burr’s reputation. While the duel didn’t put an end to Burr’s public life, his status as one of the most brilliant, interesting, and far-seeing of the founders has not survived that encounter beneath the cliffs at Weehawken. Making matters worse, there was the small matter of Burr’s trial for treason less than three years later, when he was accused of leading a motley group of disaffected military officers and fortune-seekers on an expedition to conquer Mexico (Burr’s story) or tear the Western states and territories away from the Union (Thomas Jefferson’s story).

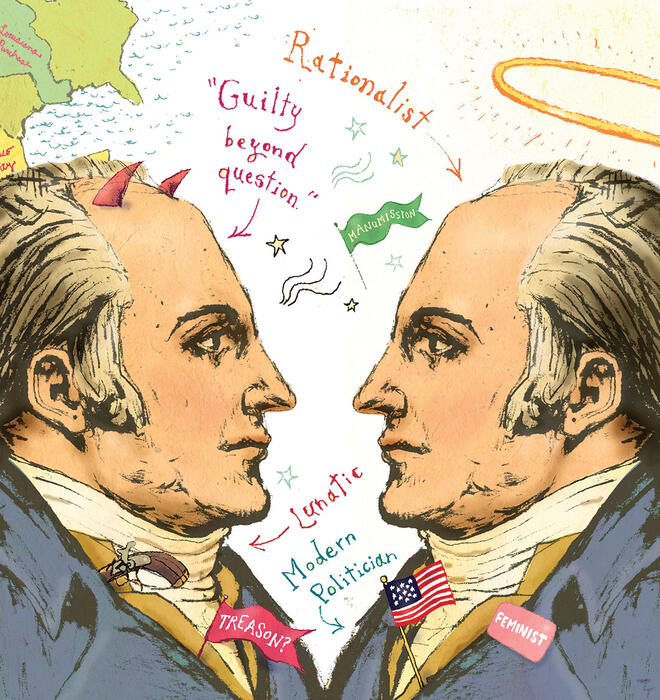

At the hands of Henry Adams and dozens of other historians, biographers, and writers of fiction, Burr — acquitted on all charges — has been portrayed as a conniver, a cynic, and a seducer. He has become an archetype, the “bad” founder, an American Lucifer who fell from grace. While Hamilton adorns the $10 bill, Burr is forgotten except when he is scorned.

Now, 200 years after his return from self-imposed exile in Europe, the third vice president at last is getting another look. During the summer, the Grolier Club in New York hosted a large exhibition of Burr memorabilia, displayed as evidence of his progressive views. In her well-received 2007 biography, Fallen Founder, Lousiana State University historian Nancy Isenberg makes a convincing case that Burr has been unfairly maligned. Sean Wilentz, Princeton’s George Henry Davis 1886 Professor of American History, argues in his Bancroft Prize-winning book, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln, that Burr deserves recognition for pioneering many modern political tactics. While it may be too much to call this attention to Burr a rehabilitation, it is, at least, forcing a re-examination and even something of a reappreciation.

In many ways, Burr is more appealing to us than he was to his contemporaries. The son and grandson of two ministers and Princeton presidents, Aaron Burr and Jonathan Edwards, both of whom died when Burr junior was a boy, he grew up with the Enlightenment’s faith in human reason. Young Burr always was a rationalist, and in later life came to embrace Jeremy Bentham’s Utilitarianism. Even his detractors conceded his genius. He first applied to Princeton when he was just 11 years old, and was accepted at 13.

Physically, Burr was barely taller than James Madison 1771 and already balding as a young man, but he had piercing dark eyes and women swooned for him. Sexually voracious throughout his life, Burr was also a proto-feminist who appreciated Mary Wollstonecraft’s revolutionary book, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, as “a work of genius” and gave his only child, his daughter Theodosia, the same classical education he would have given a son.

Part of Burr’s problem, from a historian’s perspective, is that for most of his life he was content to stand apart — “a faction unto himself,” as Wilentz puts it in his book. He had a distinguished military career during the Revolution but little respect for George Washington’s generalship, and he declined an offer to serve on Washington’s staff. In 1788, he allied himself with anti-Federalists in opposing the new federal constitution and declined to participate in New York’s ratifying convention.

As a state assemblyman, Burr supported laws for the manumission of slaves (although he owned slaves when the practice was still legal in New York). By the time he was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1791, many saw him as a rising national leader. He was promoted as a possible vice-presidential candidate in 1796, and four years later, in 1800, he was Thomas Jefferson’s running mate. It was Burr, in fact, more than anyone who secured the election for Jefferson, although he soon would be accused of trying to steal it from him.

In those days, presidential electors were chosen by the state legislatures, and New York’s legislative elections were held early, in April. By outmaneuvering Hamilton and the Federalists, and briefly uniting the bickering Republican factions, Burr secured New York for Jefferson. He did it by employing what we would admire as a strong political ground game. Rather than affecting to be above politics, as Jefferson did, for example, Burr campaigned openly, made detailed lists of likely voters and party donors, and turned his house into a campaign headquarters.

Then an odd thing happened. Although Burr was Jefferson’s running mate, candidates did not run as a formal ticket, as they do today. The candidate receiving the most electoral votes became president, while the runner-up became vice president. When Jefferson and Burr finished with the same number of electoral votes, the election was thrown, for the first of two times in American history, to the House of Representatives. Although Jefferson’s partisans later accused Burr of maneuvering to steal the presidency for himself, evidence suggests that it was Jefferson who engaged in behind-the-scenes arm-twisting that succeeded, after 36 ballots, in giving him the presidency.

Many assumed that, as vice president, Burr eventually would succeed Jefferson, but the faction of one found himself assailed from all sides. The aristocratic Republican families in New York viewed him as an interloper. Jefferson feared that he might challenge his protégé and fellow Virginian, James Madison, for the presidency. Burr maintained cordial relations on both sides of the aisle, but that only deepened suspicions about him. When the Republicans met in early 1804 to select their candidates, Jefferson arranged to have Burr dumped in favor of another New Yorker, Gov. George Clinton.

Burr’s bitterest enemy was Hamilton, who recognized Burr as a rival to his own political power in the state. Hamilton hated Burr, and the feeling was mutual. Where Burr was direct, though, Hamilton dealt innuendo and character assassination with gusto. Much of Burr’s reputation for being unprincipled and untrustworthy, in fact, came first from Hamilton’s poison pen. Hamilton’s recklessness frequently got him into trouble; he had challenged or been challenged to duels 11 times, though none — until the encounter with Burr — had reached the dueling ground. Indeed, to read Isenberg’s account of Hamilton, it is surprising that no one shot him sooner.

Shortly after Burr lost the New York gubernatorial election in 1804, a small item appeared in an Albany newspaper in which a Dr. Charles Cooper quoted Hamilton making disparaging remarks about Burr’s character. Hamilton had been making such comments for years, but always behind Burr’s back. This was the first time the press reported such words as coming directly from Hamilton’s mouth, and they required an explanation. When Hamilton gave an evasive and unsatisfactory answer, Burr demanded satisfaction.

Dueling was illegal in New Jersey but rarely was prosecuted, so many New Yorkers took their conflicts across the river. Often, duels were a kind of a theater: Both parties would fire into the air, honor would be satisfied, and everyone would go home in one piece. That did not happen at Weehawken. Accounts conflict as to whether Hamilton fired first or even fired at all. It does appear that the guns Hamilton insisted on using had a larger bore than usual and that his had a special hair trigger, which could have given him an unfair advantage. Ironically, Isenberg suggests, if Hamilton had used Burr’s smaller set of dueling pistols, he might have survived his wound.

Although he was investigated for murder in both New Jersey and New York, Burr managed to avoid the law simply by staying out of their jurisdiction. Incredible as it seems, he was hardly a pariah when he returned to Washington. The Federalists shunned him, but many Republicans greeted him warmly, and Jefferson even dined with him at the White House. Indeed, that fall Burr enjoyed perhaps his greatest moment, presiding as vice president with dignity and impartiality over the Senate impeachment trial of Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase. Two days before he left office in March 1805, Burr delivered a farewell address that left many senators, including his political enemies, in tears.

As a future candidate, though, Burr was finished, and his career took a sharp turn. The country buzzed with rumors of war against Spain, which controlled the territory adjacent to the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase. As notions of America’s Manifest Destiny began to emerge, many members of both parties hoped to “liberate” Mexico, whether the Mexicans wanted liberation or not. In the event of war — but only if, Burr later insisted — he proposed to lead a private army into Mexico City and install himself as the head of a free republic.

The term for this sort of freelance expedition was a “filibuster” (it did not become associated with long-winded congressional debates until the 1850s). Throughout 1805 and 1806, Burr traveled around the country assembling about 80 supporters, including Jonathan Dayton 1776 and then-Maj. Andrew Jackson. Burr’s chief confederate was Gen. James Wilkinson, and here was a real villain. At the same time Wilkinson was preparing American military forces for a possible war in New Orleans, he was taking bribes from the Spanish government, and he had participated in an earlier plot to break Kentucky away from the United States.

What was Burr up to? That remains a question. Although filibusters weren’t exactly legal — leading one in peacetime was a misdemeanor — they were not as traitorous or as uncommon as we might think today. During the Revolution, for example, American Gen. Richard Montgomery had led one into Canada to free the Canadians from the English. Furthermore, anyone who could read a newspaper knew that Burr was organizing some sort of armed expedition, and this certainly included President Jefferson, who met with Burr during one of his recruiting trips.

But Burr also spent a lot of time in the wilderness with dodgy characters, and there is at least circumstantial evidence that his intentions were more malign. Anthony Merry, Great Britain’s ambassador to the United States, quoted Burr in one of his dispatches as offering to help the British take western territory from the United States in exchange for half a million dollars. Burr himself made some impolitic remarks — perhaps in jest, perhaps not — about wanting to invade Washington and toss Jefferson and Congress into the Potomac.

Burr arranged to store supplies at a place called Blennerhasset Island in the Ohio River, which would serve as a rendezvous point for the expedition. Rumors that he was up to something led the U.S. attorney in Kentucky to indict Burr for treason, but Burr, with the help of his lawyer, Henry Clay, got the charges dismissed. Wilkinson, though, began to fear that his own illegal activities would come to light and decided to save himself by betraying Burr in a letter to Jefferson. Wilkinson, in fact, painted himself as a hero who had uncovered the nefarious plot.

Jefferson, who had been oddly passive about Burr’s activities, suddenly forwarded to Congress evidence he had received of the alleged conspiracy and pronounced that Burr was guilty “beyond question” — before Burr even had been charged. Burr surrendered to authorities in Mississippi and was taken to Richmond for a trial presided over by Chief Justice John Marshall.

Marshall, a Federalist, was no more a friend of Jefferson’s than Burr was. Treason is the only criminal offense for which the Constitution specifies a standard of proof: an overt act of aggression corroborated by two eyewitnesses. The alleged overt act was a small gathering of Burr adherents, who may or may not have been armed, on Blennerhasset Island. But even the government had to concede that Burr had been hundreds of miles away on the day the so-called army had assembled. To surmount this obstacle, prosecutors alleged that Burr was guilty of “constructive treason” — in other words, that he was responsible because he had set the conspiracy in motion, whether or not he actually had participated in the overt act.

Burr was ably defended by Luther Martin 1766, another longtime enemy of Jefferson’s known as “Old Brandy Bottle,” who characterized the government’s case as “will o’ the wisp” treason. “It is said to be here and there and everywhere,” Martin said, “yet it is nowhere.” Wilkinson, who was involved in the plot up to his eyeballs, avoided Richmond until the trial was almost over, and then was forced to concede that he had altered a key piece of government evidence. Marshall ruled that the government had failed to prove an overt act, and so the jury found Burr not guilty. Burr later was acquitted of leading a filibuster, too, when the government could not prove that it had been aimed at Spanish territory.

Although Isenberg argues persuasively that Burr never intended to lead a secessionist movement, what he might have done had the opportunity presented itself never will be known. Former president John Adams wrote to Benjamin Rush 1760 that Burr must have been “an idiot or a lunatic” to have gotten involved in such a mess, adding, “I never believed him to be a fool.” Even under the most charitable interpretation, Wilentz argues, Burr deserves history’s censure for sowing dissension among soldiers at a time when the American tradition of civilian control over the government was not yet a sure thing.

“Burr spent a lot of time playing on the frustrations the old-order military people had with Jefferson,” Wilentz says. “And that, to me, is dangerous. It may have made sense politically, but in terms of the institutions of American government, it was very dangerous [for Burr] to be fomenting a major’s plot.”

Broke, shunned, and fearing for his safety, Burr spent the next five years in Europe. After the British kicked him out (possibly because of American pressure), he moved on to Sweden, Germany, and France, where he tried to sell Napoleon on his idea of conquering Mexico. Returning to New York in July 1812, he hung out his shingle, representing many widows and orphans and operating what Isenberg calls one of the country’s first family-law practices. Politically and socially, however, Burr remained poison, and tragedy was never far away. His only grandson died at the age of 10, and just months later his beloved Theodosia was lost in a shipwreck. Many of Burr’s papers are believed to have gone down with her, which may explain why he can be such an enigma.

Recent additions to the scholarly literature, such as Isenberg’s and Wilentz’s books, have had a positive effect on Burr’s reputation, says Elaine Pascu, a senior associate editor of the Jefferson Papers project, which is headquartered at Firestone Library. But as for reclaiming his place in history, Pascu adds, “I think that will take a little while yet.”

Isenberg believes that her book has revived popular interest in Burr and will cause future historians to rethink the obloquy that has been heaped on him over the generations. Her portrait of Burr and his dealings with the Founders frees him “from the stranglehold of myth” by focusing on the outsized role that mudslinging newspapers, personal rivalries, and the struggle between the New York and Virginia factions of the early Republican party played in the emergence of the party system. But she does not expect an end to the debate. “Burr’s character will continue to be attacked,” she predicts, “because Americans like simple stories with heroes and villains.”

In the end, Burr outlived his enemies, although he spent the remainder of his life living in obscurity and intermittent poverty. He died Sept. 14, 1836, less than five months after a group of Virginia and Tennessee filibusterers defeated the Mexican army at the Battle of San Jacinto, securing independence for the Republic of Texas. The leader of that insurrection, Sam Houston, became an American folk hero.

Today, Alexander Hamilton lies beneath a splendid obelisk in the graveyard of Trinity Wall Street in lower Manhattan. Aaron Burr is buried in the presidents’ section of Princeton Cemetery, at his father’s foot. The surrounding gravestones are all in neat rows, but Burr’s is the only one in that section that is out of line. It is as if he was squeezed in, an afterthought for all eternity.

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

For the record

This a corrected version of a story from the Oct. 10, 2012, issue. Firestone Library is the headquarters of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson project. The location was given incorrectly in the earlier version.

5 Responses

Norman Ravitch *62

4 Years AgoHeroes and Villains

History demands constant reevaluation, and our founders, good and bad, are not exempt. Still for purposes of civic education some of these founders are useful with exaggeration for our youth. But our youth know less about Washington, Jefferson, or Lincoln than they do about current celebrities. It may be too late for this country. Our violent behaviors and rhetoric would indicate more and more decline. Put not your trust in Americans, my friends, Princetonians or not.

Dale Coberly

4 Years AgoBurr, Hamilton, and Jefferson: A Study in Character

Burr, Hamilton, and Jefferson: A Study in Character (Oxford University Press, 2000), a book by Roger Kennedy, makes essentially the same case for Burr as you make here, maybe better. I would recommend it to anyone who cares about the subject, or subjects.

Paul Matten ’84

10 Years AgoAaron Burr, pro and con

Within the Revolutionary generation, the leader with the best judge of talent and integrity was none other than George Washington. Tellingly, Gen. — and later, President — Washington wanted little to do with Aaron Burr Jr. 1772 (feature, Oct. 10), given the latter’s deserved reputation for intrigue of various sorts.

Whether it be his well-documented moral deficiencies, or his infamous duel with the genius Alexander Hamilton, or his anti-American association with the nefarious James Wilkinson post-duel, Burr cannot be redeemed. He was a scoundrel, and we alumni must accept the fact that he is a notorious Princetonian.

M. Vernon Ordiway ’54

10 Years AgoWoodrow Wilson on Aaron Burr

When reading the Oct. 10 feature on Aaron Burr Jr. 1772, I recalled that Woodrow Wilson 1879 in his multi-volume American history of the early 1900s noted at the time of the Mexican War that Burr’s ideas of decades earlier were not the accepted position. I thought Wilson was expressing approval and saw it as an expression of Princeton pride.

Edwin L. Brown *61

10 Years AgoAaron Burr, pro and con

After reading this careful weighing of Burr’s considerable merits alongside the familiar demerits, I tend to look at him more as I view LBJ, that latter-day “deeply flawed idealist” — to be squeezed among our 25 most influential alumni in place of Donald Rumsfeld ’54?