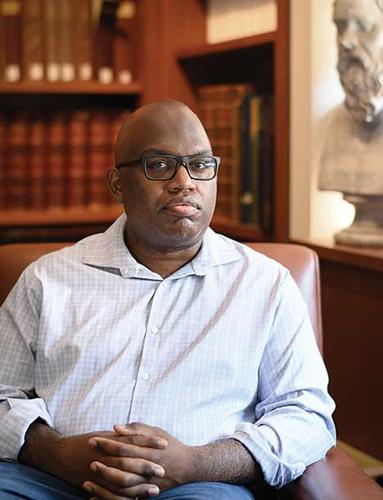

The story has the clarity of a fable: In the library of a New York homeless shelter, an immigrant boy finds a book that introduces him to the glories of ancient Greece and Rome. Years later, after navigating hardship and embracing opportunity, he grows up to teach classics at Princeton.

That story — told in Undocumented: A Dominican Boy’s Odyssey from a Homeless Shelter to the Ivy League, the 2015 memoir of Princeton professor Dan-el Padilla Peralta ’06 — might read as an inspiring testament to the transcendent power of the oldest great books.

But in recent years, Padilla Peralta has articulated a bleaker moral to the tale: His discovery of classics, Padilla Peralta says, marked the start of an education in marginalizing his Black and Latinx identities.

“Classics was a cheat code for mastering whiteness,” he writes in his contribution to a forthcoming scholarly book on race in antiquity. “Mastery of this cheat code would entail … internalization of the sense that my own personhood, and the histories that pulsed through it, had to be subordinated to a body of knowledge that radiated Western authority.”

Padilla Peralta’s public interrogation of his personal history comes at a charged moment for his discipline, as classicists undertake a parallel interrogation of their field’s problematic past and flawed present. A specialist in Roman history and religion, Padilla Peralta has become a leading voice in this struggle over how classics — historically a proudly elitist discipline built on a Eurocentric conception of intellectual inheritance — can remake itself for a changed world.

Especially among younger classicists, there is “a real energy and a real desire to transform the field into something that is avowedly anti-racist and anti-white supremacist,” says Christopher Waldo, an assistant professor of classics at the University of Washington-Seattle and co-chair of the Asian and Asian-American Classical Caucus. “This is a really interesting moment in the history of classics as a discipline, where those questions are being asked.”

Such questioning is nothing new in the academy: Scholars in such fields as history, English, anthropology, and religious studies have spent decades reorienting their research agendas and reimagining their curricula in light of contemporary understandings of race, class, and gender, a process sometimes called “decolonization.”

More than 30 years ago, classics seemed on the brink of a similar reckoning, when Martin Bernal of Cornell, a historian of modern China who had migrated to ancient studies, began publishing his three-volume Black Athena. Bernal argued that Greek civilization had African and Asiatic roots, and he analyzed the role that white supremacist ideology had played in the development of the discipline of classics in the 18th and 19th centuries. But when classicists debunked Bernal’s factual claims about the ancient past, they also tossed out his critique of the discipline’s history.

That was a mistake, some scholars now say. Bernal “may be wrong about Socrates, but he’s not wrong about the way in which the discipline was embedded in this discourse on white supremacy,” says Jackie Murray, associate professor of classics and Africana studies at the University of Kentucky at Lexington. “He was not wrong about that.”

Classics: Enshrined in the very name of the field is an unquestioned assumption that its subject matter — the civilizations of ancient Greece and Rome — represents the best of human culture. But that claim, and its implicit downgrading of ancient civilizations rooted in China, India, Africa, and the Middle East, grew out of a specific historical moment, says Princeton historian Anthony Grafton, who specializes in the cultural history of the Renaissance. “From the late 18th century on, as classics began to form as a discipline, one of the things classicists began to believe was that Greece and Rome were the preeminent cultures of the ancient world,” Grafton says. “In the 16th or 17th century, there were lots of people who didn’t believe that.”

Along with the presumption of Greco-Roman superiority came a story about these civilizations’ uniquely foundational role in the development of European culture — a European culture itself conceived of as superior to the cultures of other regions, especially regions colonized by European powers. Across the British empire, men who had learned Latin and Greek in the schoolroom instituted classical curricula as part of a supposedly “civilizing” mission aimed at remaking indigenous people in the image of their colonizers.

Crucially, the ancient cultures studied by classicists, as well as the European culture those ancients were said to have founded, were understood to be white. Classics, along with Egyptology, “developed as the teaching arm of the ideology of white supremacy,” says Shelley P. Haley, a professor of classics and Africana studies at Hamilton College, who is the first Black scholar to serve as president of the Society for Classical Studies. “We need to examine the context in which classical studies grew up, and that’s what we need to dismantle.”

The racial suppositions implicit in the original conception of the discipline represented a historical distortion, scholars say. Classical historians today agree that the ancients had no concept of “whiteness” in our modern sense: Although ancient societies were hierarchically organized and sometimes oppressive, those hierarchies were not based on skin color. In the Renaissance, “scholars were perfectly aware that ancient Rome was an ethnically varied city and that people of African and Jewish and Arabian descent became Romans,” Grafton says. “In the 19th century, there was a great effort not to recognize that.”

Accordingly, despite the historical truths about the ancient world, genocidal racists and slaveholders across the centuries — from 16th-century Spanish conquistadors to Southern Confederates to Nazi leaders — found authority for their twisted racial theories in such classical writers as Aristotle, who famously argued for the existence of “natural slaves.”

Contemporary right-wing extremists and conspiracy theorists similarly root their identity in an imagined lily-white classical past. In 2016, the white supremacist Identity Evropa movement began blanketing college campuses with recruitment posters bearing a picture of the second-century Roman statue known as the Apollo Belvedere. Some of the rioters who stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 came costumed as ancient Greek and Roman warriors. And Marjorie Taylor Greene, the conspiracist Republican congresswoman from Georgia, wears a facemask emblazoned with “Molon Labe,” an ancient Greek phrase roughly translated as “come and take them,” which has become a slogan of the gun-rights movement.

“An interest in classics is this quick signifier of a certain kind of identity politics — white male identity politics — and a signifier for a set of values,” says Donna Zuckerberg *14, an independent scholar who authored a 2018 book about the alt-right’s embrace of classics.

Indeed, contemporary white supremacists aren’t entirely misreading classical texts, says Curtis Dozier, an assistant professor of Greek and Roman studies at Vassar College who directs Pharos, a website devoted to documenting and debunking hate groups’ appropriations of the classical past. The ancients held slaves, deprived women of civil and political rights, limited the citizenship of immigrants, and glorified the violent imposition of cultural values on conquered peoples. White supremacists “didn’t really need to misrepresent antiquity to support their politics,” Dozier says. “They found in the ancient world a way of organizing society that was very congenial.”

While contemporary scholars may reject the alt-right’s embrace of classicism, presuppositions about the classical lineage of a superior Western culture still subtly permeate the discipline’s self-definition, some classicists say. “Great Books” courses start with Homer and Plato; beleaguered classics departments justify their continued existence by calling their field the foundation of Western civilization. “The whole field has been so myopic. It has been focused on Europe,” says Haley, the Society of Classical Studies president. “We can talk about India, we can talk about Syria, we can talk about China, we can talk about Numidia, Nubia, Ethiopia, Egypt — but we don’t.”

Today, those questioning the discipline tend to put scare quotes around the term “Western civilization,” arguing that the concept obscures the complex lineages of European culture and the ways that classical texts also influenced, and were influenced by, non-European societies. Ultimately, these scholars say, relying on a simplistic narrative of foundationalism carries an implicit message about whom classical texts belonged to in the past, and who should study them now — a message that Waldo, the University of Washington scholar, summarizes as, “We are Western civilization, and you people over here — even if your forefathers were also reading Aristotle and Galen in the ninth century — you aren’t.”

Over the decades, however, scholarship has changed, many classicists say. The horrors of World War II inspired serious study of Greco-Roman slavery. In the 1970s, an influx of female scholars brought new attention to the lives of women in the ancient world. More recently, classicists have studied immigration to ancient Athens and undertaken more so-called “reception studies” examining how classical texts have been used — for example, by the Britons who colonized India.

Classical historians today agree that the ancients had no concept of “whiteness” in our modern sense: Although ancient societies were hierarchically organized and sometimes oppressive, those hierarchies were not based on skin color.

To some, these changes suggest that the current critique is overblown, a response to contemporary racial concerns rather than to anything happening now in the discipline itself. Although much criticism of the field’s history is valid, “they’re points that have been made for decades, and, for the most part, dealt with for decades,” says a U.K.-based scholar who requested anonymity to avoid online vitriol. “No serious classicist thinks that you should draw a line around the Greeks and Romans.”

But the wider world’s understanding of classics hasn’t caught up to the reality in contemporary academia, and like so many aspects of American life, the debate over classics has become angry and politically polarized. Last winter, when The New York Times Magazine profiled Padilla Peralta and explored his critique of the discipline, conservative pundits reacted with outrage (“The moronic social-justice war on classics threatens our civilization,” the New York Post headlined one column), and Padilla Peralta received such alarming death threats that the University removed his email address from the classics department’s website.

“A lot of us are saying, ‘Look, all our scholarship since the 1970s has been moving in this direction of trying to reflect more accurately what’s happening in the ancient world. Why don’t our departments and our hiring and the classes we teach reflect this?’ ” says Rebecca Futo Kennedy, an associate professor of classical studies, environmental studies, and women and gender studies at Denison University. “But when you put that out into the public, and you say, ‘This is who we actually are; this is who we’ve been for decades,’ all those people who have this vision of classics as supportive of elite, white, Christian Western civilization see that as an assault on the Euro-American identity of whiteness.”

Although some scholars believe that the discipline’s problematic history gives today’s classicists a unique anti-racist responsibility, not everyone agrees. “Academic subjects do not exist outside the culture in which they’re studied,” Mary Beard, the Cambridge University scholar who is perhaps the best-known living classicist, told The New York Times Magazine last spring. “So of course classics have a toxic history. Nuclear physics has a toxic history. Anthropology has a toxic history. It’s extremely important to look at it and face up to it, but classics wasn’t responsible for fascism.”

But such formulations oversimplify the nature of the challenge facing the field today, say Padilla Peralta and others: Just because contemporary classicists no longer cite Aristotle to justify slavery doesn’t mean they have fully embraced the contributions of scholars of color. Accurate data on the profession’s demographics are hard to come by, but classicists agree that their ranks are overwhelmingly white. In the past few years, two successive online message boards where classicists shared information about the difficult academic job market shut down after anonymous commenters repeatedly attacked fellow scholars, especially women and people of color. And when Padilla Peralta examined the articles published in three leading classics journals between 1997 and 2017, he found that more than 90 percent were by white authors.

That kind of imbalance hurts the field, he says. “The identities you inhabit have a very powerful effect on the kinds of questions you ask, or choose to ask, about the materials you study,” Padilla Peralta says. “The most richly imagined fabrics of the past are those that involve the greatest number of people from as many different view- and vantage points as possible, and anything short of that is intellectually impoverished.”

Historically, the discipline of classics has prided itself on its exclusivity: Classicists, masters of two complex dead languages and an array of difficult texts, often saw themselves as the most brilliant minds teaching the toughest material to the best students. But today many classicists view that reputation for exclusivity as a burden — even a threat to the field’s continued survival.

Although classics once lay at the heart of the Western university curriculum, it is now a small field, even among the embattled disciplines of the humanities. A 2017 survey of four-year institutions, conducted by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, found an estimated 269 classical studies departments nationwide, with an average of seven faculty members and eight graduating majors apiece. By contrast, the same survey found an estimated 1,062 English departments, with an average of 23 faculty members and 31 majors, and 921 history departments, with an average of 17 faculty members and 26 majors.

Princeton’s classics department, with 19 faculty members, is far larger than the national average but graduates about the same number of undergraduate majors — eight in 2021. Two years ago, in an effort to diversify the ranks of its graduate program, the department began offering a predoctoral year of funding to promising students who need extra time to prepare for advanced study. Four students have been admitted under the program, Princeton classics professor Joshua Billings says, and other universities have followed Princeton’s lead and set up similar programs.

But a more recent initiative has been far more controversial. Last spring, the classics department announced that, in an effort to attract a larger and more diverse cadre of students, it would no longer require undergraduate concentrators to study Latin or Greek. Although the department is still offering the same number of language classes, the move drew fire, with online critics arguing that eliminating the requirement represented either a retreat from rigor or a patronizing suggestion that students of color couldn’t master difficult languages.

In fact, says Billings, the department’s director of undergraduate studies, the change is a way of ensuring that talented students won’t be discouraged from studying classics because they lack high school preparation in ancient languages. A 2017 study of foreign-language education, sponsored by the U.S. Defense Department, found that about 210,000 high school students were enrolled in Latin courses nationwide, compared with 7.3 million studying Spanish and 1.2 million taking French. Although the study did not parse its data by school sector, classicists say it is common knowledge that private schools are far likelier than public ones to offer Latin and Greek. For students who arrived at Princeton without a background in either language, the mandatory four semesters of language study, on top of the concentration’s other requirements, were “really a barrier to our recruitment of students,” Billings says.

But if eliminating language requirements is a controversial approach to modernizing the discipline, alternative reform strategies — sometimes promoted with rousing rhetoric about “burning down” classics to build it back better — also have their critics.

Perhaps the least radical suggestion amounts to rebranding: Replace the elitist label “classics” with a more neutral designation, such as “ancient Greco-Roman studies” or, ideally, “ancient Mediterranean studies,” to reflect a more inclusive approach to the subject matter.

Padilla Peralta embraces this proposal — to a point. “I am for renaming because I think it’s a good idea to be more honest in advertising,” he says. But renaming “is usually understood as a way of heading off more comprehensive, and potentially much more intrusive, readjustments to the scope of departmental practice,” he says. “It is for me important not to let that stand as lip service to transformation.”

More radical is the suggestion that existing interdisciplinary classics departments should be eliminated entirely, with their faculty members redistributed to more specialized departments — literature, history, philosophy, archaeology. “There are many things worth studying that the Greeks and Romans have produced,” says Walter Scheidel, a professor of classics and history at Stanford. “It’s just not obvious that it should be configured the way it was set up 200 years ago, as a separate field that has its own very exclusionary requirements.”

Such suggestions alarm classicists at institutions with less money and prestige, where a confluence of forces — from administrative cost-cutting to student demand for vocational preparation — is already squeezing humanities disciplines. Earlier this year, Howard University announced plans to disband its venerable classics department, the only one among the nation’s historically Black colleges and universities.

“It can be grating for people at smaller universities to hear all this language of dismantling, because that’s exactly what the higher-ups want to do. They’d love to dismantle us. They just want an excuse,” says James Kierstead, a senior lecturer in classics at New Zealand’s Victoria University of Wellington. “You can have that burn-it-down-build-it-up conversation at Princeton, but the burn-it-down conversation at Victoria University of Wellington just looks like smoldering ashes, and then they do more engineering.”

Other classicists want a different approach, a way of placing one of the oldest university disciplines at the center of contemporary conversations about the socially constructed nature of racial categories. A reconceptualized classics could give students a way of examining “how structures of inequality and oppression in the modern world have come into existence, and how they feed themselves, and simultaneously how long they’ve existed and yet how arbitrary they are,” says Dozier, of Vassar.

“The tendency to dominate other groups is something that is one of the human dilemmas,” says Murray, of the University of Kentucky. “The reason why I was interested in studying the classics was because it’s another world, where other people have different solutions. The point is to look at the past as another window onto the human condition, instead of looking at the past as a place to justify current economic and political and ideological points of view.”

For Padilla Peralta, even that reconceptualization may not be enough to rescue classics from its entrenchment in systems of privilege — the socioeconomic privilege that enabled so many classicists to study ancient languages in the first place, and the Eurocentric intellectual privilege that adjudicates which kinds of inquiries count as legitimate modes of academic study, and which do not.

“How are you going to keep this knowledge practice alive in ways that are more inclusive, that are more dynamically open?” Padilla Peralta asks. “What would you have to do? What kinds of redistribution would have to take place?”

Padilla Peralta’s engagement with such issues stretches beyond the bounds of his discipline: In the summer of 2020, he co-authored an open letter to Princeton’s administration calling for wholesale changes — to curriculum, hiring, training, and recruitment — aimed at making the University “for the first time in its history, an anti-racist institution.” The debate over classics, he suggests, implies another, deeper question: What role should extraordinarily wealthy universities like Princeton play in a radically unequal world?

“The fact that I had to latch onto this Greek and Roman business in order to get out of the ’hood — this is not something to be happy about,” Padilla Peralta says. “What it speaks to is the inherent precarity of the lives of those folks for whom these kinds of opportunities are never, ever going to materialize.”

Deborah Yaffe is a freelance writer based in Princeton Junction, New Jersey.

Editor’s note: This story has been slightly revised since its print publication.

18 Responses

Douglas P. Seaton ’69

4 Years AgoA Place of Pride for Greco-Roman Classics

I read “The Color of Classics” (October 2021) and Douglas B. Quine ’73’s letter (December 2021), continuing the polemic against the classics, with disappointment.

The Greco-Roman classics should be studied in an entirely different way than the other ancient civilizations Mr. Quine mentions, for very good reasons.

With the exception of the Hebrew bible, the epic of Gilgamesh, some calendars, ruler lists, astronomical notes, palace and merchant inventories, and a few inscriptions and treaties, and virtually nothing at all in the case of the ancient Indian societies, the Etruscans, the Mycenaeans, and the Mayans, there are very few surviving other ancient writings to study and provoke thought, except for ancient Chinese Society.

But in the case of Greece and Rome, there is an enormous body of written work, from history, biography and poetry, to philosophy, epic and mythic stories, available to all, irrespective of race or national heritage. What is more, these are works which continue to shape Western Civilization.

The histories, law, and political commentaries of Greece and Rome, for example, were the source of our founders’ ideas on constitutions, separation of powers, super majorities, checks and balances, republican and democratic institutions, and the rule of law, restraining all, even the rulers.

Unless you despise and seek to erase 3,000 years of Western Civilization (and there are many who do), to be replaced by a to-be-determined absolutist left-wing (or right-wing) paradise, you should fervently hope that the Greco-Roman classics continue to be studied and given pride of place, as well, over the study of other ancient societies.

Meredith Davis

1 Year AgoRemoving Distortions from Study of the Classics

The entire article is about advancing the study of the classics by removing some of the distortions to that history from the 19th century onwards. No one involved is suggesting the cessation of that study. A person does not pursue a Ph.D. in classics — learning several ancient languages along the way — because they do not want to further knowledge of the classics! Right?

R. Carlton Seaver ’68

4 Years AgoDissolving the Department

On reading your recent “The Color of Classics” in the October 2021 issue, it is obvious that the only way to deal with the concerns raised by younger faculty in the classics department is to dissolve the department, sending faculty involved in the Greek and Latin language to whatever department deals with older, usually extinct languages (think Hittite and Aramaic), Greek and Latin history professors to history, classics philosophy faculty to the philosophy department, and so on. Of course, tenure, endowed chairs and offices in East Pyne should follow those former classics professors.

The idea of classics was always an anomaly. The “glory that was Greece” only lasted a century (arguably, 506 to 403 BC), and the influence of Rome was also short. But educated men thought that Greece and Rome intellectual thought was the basis of modern Western civilization. Certainly, the founding fathers, now in bad odor, thought so. And Oxford and Cambridge called the study of Greek and Latin language, history, philosophy and literature the “greats.” But, those, of course, were the bad old days before modern sensibilities straightened us out on the limitations of western European culture and its racism, sexism and colonialism.

With all of this in mind, why should we have a classics department? Perhaps the only impediment to getting rid of it is that faculty in departments to which former classics faculty are transferred might be wary of what those former classics faculty who, with recent success under their belts, might do to their new departments.

Lloyd Axelrod ’63

4 Years AgoWhat About the Renaissance?

While it may be true that “classics’ focus on Greek and Roman cultures began in the 18th century, as the discipline was forming,” the influence of Greek and Roman culture in Europe began in the 15th and 16th century during the Renaissance. Indeed, the term Renaissance, or rebirth, refers directly to this influence. Inspired by the discovery of sculpture, architecture and texts from Greece and Rome, artists, sculptors, writers and others transformed European civilization by the study of these secular cultures. In Italy and other countries these secular influences stood side by side with the dominant Christian culture, usually with no sense of conflict between the two. The Renaissance with an important step in the transition from the domination of European culture by the Medieval Church during the Middle Ages to more secular European cultures since then. In that sense, the influence of Greek and Roman culture continues to this day.

To date the influence of Greek and Roman culture in Western civilization to the formation of the discipline of the classics is to take a narrow and poorly informed view. A more complete understanding of our roots and of who we are requires an understanding of the influence of Greek and Roman culture.

Jay Tyson ’76

4 Years AgoA More Expansive View of the Ancient World

“The Color of Classics” was a fascinating article. It highlights how, as Princeton aspires to be a universal university, the department will need to (a) change its name to something like “The European Classics” or (b) expand its curriculum, bringing in courses on the classic wisdom of Chinese, Indian, Persian and other ancient civilizations. I favor the latter approach, which would do a better job in preparing young people for their future world — a world in which their ability to work closely with people of other cultural backgrounds will be a necessity.

Dan Caner ’86

4 Years AgoFiring Up the Imagination by Studying Ancient Cultures

As a former Princeton classics major and professor at a state university, I found the discussion of Greek and Latin studies in “The Color of Classics” disappointing.

I agree that it is no longer appropriate to apply the name “classics” exclusively to these subjects, especially at postmodern universities, where knowledge practices are not meant to privilege one subject over another. But the idea that the study of Greek and Roman cultures should not exist as a distinct field at all, even as an “area study,” like other language-based cultural fields, is exasperating. The article discussed the current field solely as if it were a mechanism for sustaining privilege or hindering or helping upward mobility. I think these claims are dubious, but more to the point, the article made no mention about the value of studying such unusually complex and interconnected material as Greek tragedy or Greek philosophy (to state just my own preferences) as subjects on their own, or in relation to the ancient cultures that produced them, or as pedagogical tools for thinking about or critiquing sensitive topics such as race, gender, or ethics in modern society from a safe distance.

Over time I have only become more convinced about the value of studying ancient Greek (and to a lesser degree, Roman) culture, and wish it were more vigorously promoted at our universities. Few things at Princeton equally fired my imagination or got me interested in other fields of study.

Ramsay M. Harik ’85

4 Years AgoStudying Classics vs. Studying Racism

Pity the wide-eyed freshman who signs up for Classics 101, looking forward to discovering the wonders of ancient Greece and Rome, only to be subjected to a semester-long harangue on the evils of racism. If this is what a Princeton education is becoming — the reduction of complex worlds to a simple thumbs-up or thumbs-down dictated by the latest single-lens ideological fashion — then what’s the point? You can get as much by spending an afternoon with one of the countless “anti-racist” books now flooding the market, and for a much better price.

As a lifelong progressive, I am sickened by this betrayal of the ideals of both higher education and social justice.

Douglas B. Quine ’73

4 Years AgoThe Richness of Ancient Civilizations

The cover story of the October 2021 issue, “The Color of Classics,” observes that academic study of the “classics” concentrates on Roman and Greek culture. As a Roxbury Latin School graduate, I am familiar with that focus, but as a traveler to seven continents, I also appreciate that other highly developed civilizations existed with writing before the Romans. A number come to mind, including the Mayans (in the Americas), the Egyptians (in Africa), the Jews, Mesopotamians, Chinese, and Indians (in Asia), and Etruscans and Mycenaeans (in Europe). Other cultures in Australia, Europe, and North America maintained cultural identities through oral traditions, petroglyphs, and cave paintings.

The Roman and Greek focus reflects a narrow worldview. Classics departments should remove their blinders and embrace the richness and diversity of ancient civilizations around the world. Classics shouldn’t be a niche department; they are the portal to the longest part of human history! While the lack of poetry and prose may preclude the study of Linear B literature from Mycenae, the study of art, architecture, governance, religion, and literature from ancient civilizations will enrich us all. Where data is lacking, research opportunities abound. Some lessons from the sustainable practices (and failures) of the past might also even help us manage climate change.

Avalee Cohen s’65

4 Years AgoOn Learning Languages

In regards to requiring Latin and Greek for classics majors, I can certainly understand the pros and cons. But it seems that the soul of the English language resides in both Latin and Greek and should be required along with English courses.

A common argument to do away with Latin requirements seems to be that public school graduates don’t have the advantage of taking it in high school. It should be as it would not only help with dissecting English but help those learning a second language. Higher educational institutions should be at the forefront to work with high schools to encourage the taking and learning of many languages, not just English.

Donald McCabe ’68

4 Years AgoReasons for Studying Classics

Deborah Yaffe writes in her October 2021 cover story “The Color of Classics” as though students could only have been motivated to study classics in past years because of racism. And I take it that that is also the view of her subject, Professor Dan-el Padilla Peralta ’06.

Nowhere in her piece do the words “gay” and “homosexual” appear, even though I know the desire to study a culture where homosexuality was not stigmatized has for centuries been a major reason why people have studied the subject.

Terry L. Whipple ’67

4 Years AgoHere’s to Colorblindness

It is an interesting article on “The Color of Classics.” Yaffe quotes Christopher Waldo saying, there is “a real desire to transform the field [of classics] into ... anti-racist and anti-white supremacist.” She further states that in ancient societies, “hierarchies were not based on skin color.” Hear, hear ... here!

For the thousands of you reading this who do not know me, you cannot tell whether I’m Black or white. I could be either. William Whipple, Jr. signed the Declaration of Independence as a New Hampshire founding father, and Prince Whipple, a slave from Guinea, fought for the Union Army to earn his freedom. But Black or white, what difference should it make? You also cannot tell any other things about my DNA; nor that I was raised in a single-parent family. And my name is even bisexual. Ah, the advantages of the written word without video or color graphics.

The point is: Princeton University has always aspired to recognition as an elite institution. So it should be judged only on its merit. So, too, should its students and its faculty be selected and judged only on their merit, “not based on skin color.” Welcome to the new Alumni Council Officers (October issue, p. 8). May they add new energy to the “classical” theme of merit at Princeton, lest we become so focused on race and color that our efforts at inclusion actually become exclusionary. Don’t step over the diamonds. Meritorious achievement and fulfillment of one’s potential should be colorblind, as in the classical ancient societies.

Donald Catino ’60

4 Years AgoA War on Classics

I found the article, and Professor Padilla Peralta ’06, an example of a contemporary woke, politically polarized social justice war on the classics — a kind of “CCT” (Critical Classics Theory) alleging that “whiteness” is embedded in our hearts, minds, culture, and understanding of the classics.

I am so glad that I graduated 61 years ago and did not have to deal with this nonsense.

Amelia Brown ’99

4 Years AgoThe Diversity and Value of the Humanities in 2021

I grew up in rural Vermont, dug purple glass and broken china up out of the old stone wall behind our house, and decided to become an archaeologist in 2nd grade. There were no foreign-language classes at my school, so my first love was for Egypt and King Tut’s Tomb, and it was only in 7th grade when I started to study Latin that I turned to Rome, and then when I attended the Ithaka program on Crete, to Greece.

Diversity in Vermont was much more about where your parents came from (here or not), or what religion you were (protestant, Catholic, Jewish), than about race. Some of my schoolmates were adopted from Korea, while others were refugees from El Salvador, whose fathers were ministers like mine. When my father completed his degree in ministry at B.C., there were many new and diverse churches to visit as his classmates were ordained — in New York City, Boston, or back in Vermont.

My mom had a classmate from the Dominican Republic, and we went to her poetry reading and learned about the dictator she had fled. Besides my parents, family, and teachers, I looked up to the Red Sox, and especially the captain. When two refugee boys from the Caucasus murdered Boston Marathon runners, it was Big Papi, David Ortiz, who made me feel safe again in my own city, confident of our shared community.

My sacred sites as a kid were the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the MFA, and Fenway Park, as much as the churches, synagogues, or other more free-form worship spaces we went to in the quest to build a new sort of Christianity in harmony with ecology and humanity. My dad had the Blue Marble image of Earth from space on his wall, and the motto “Think Globally, Act Locally.”

That’s still what I’m trying to do now, as a professional classical archaeologist, a scholar of Hellenism in late antiquity, and a university senior lecturer of both Greek history (in English) and Greek language. I’m a sort of minority, as the only American among my eight wonderful colleagues in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Queensland. We teach majors in ancient history, and also majors in the classical languages, and we’re thrilled to do both. In Australia and New Zealand the spectre of professionalisation of the university sector is very real — just last year the national Senate voted to increase the fees for students studying the humanities. We have to justify our existence every week, and in every forum imaginable.

And we do, because we love what we do and our students love it. But it’s great to teach classics not just because it’s an intrinsically interesting field, and it stretches from Spain to India in antiquity, and much farther later in time. It’s also because it makes students think about humanity, what it is capable of, for better and worse, in deep detail, glowing colours, endlessly fascinating stories.

There are always new mysteries to solve — the horizon is limitless — just as in microbiology or astronomy. You don’t need to study ancient history, Latin, or Greek to pursue classics, all you need is curiosity and opportunity. That means the support of your parents, or your society, but it also means that those subjects are offered — that primary-school history can lead to Greek history and language at uni and a career drawing mythological comics, or primary school English can lead to a philosophy Ph.D. and an Antigone in translation feminist reading group.

It’s more important than ever that we all work together to preserve diversity of opportunity, and academic offerings, so that these subjects are taught by scholars who have found their academic community, and so that kids can grow up to know as much about humanity — for better or worse — as about volcanoes or insects. Then they will ask questions, look for evidence, and not accept anything at face value.

Bill Taylor ’80

4 Years AgoA Global View of Classics

I read the article on reforming the classics department (“The Color of Classics,” October issue). My father was a classics major in the Class of 1933. I recall a conversation with him in the 1980s. I was telling him about the yoga I was practicing and he said, “The only real civilization is Western civilization.” A moment later, after reflecting, he said, “Actually there is some value to yoga.” Change and revision are good things. I think reorganizing the Department of Classics to include Chinese, Indian, Arabic, African, and Native American and other indigenous wisdom, whether written or oral, would create a complete “classics department.” After all, this is human civilization.

The book The Man Who Loved China by Simon Winchester depicts the life of Joseph Needham, who brought awareness to the West the many advances in knowledge and technology created first in China. Other breakthroughs in math and astronomy came in the Arab world. Likewise, the Indus River culture created yoga and much more, and many cultures around the world understand the value of mastering breath and ate a diet that required effort to chew as a way to preserve good health, straight teeth, and strong bones. These were lost in the soft “civilized” diet that followed agriculture and exploded in the industrial revolution in which so many suffer from crooked teeth and degenerative disease (depicted in the book Breath by James Nestor).

A revamped classics department could advance all this knowledge for the benefit of all. A survey of the many cultures through coursework could be followed by thesis work in the student’s area of interest in which they could go deeper into a culture and its philosophy, science, art, or health. Princeton could then be a leader in bringing these ideas into greater circulation, in the world’s service.

William S. Barker ’56

4 Years AgoJudeo-Christian Influences in Classics

The article on contemporary classics departments was fascinating (“The Color of Classics,” October issue). At Princeton I majored in history but had what could be considered a “minor” in classics. As one who has taught Western Civ to college freshmen for almost 15 years and church history (ancient and medieval, Reformation and modern) at the theological level for more than 25 years, I found it interesting that one of the rebranding possibilities for the classics department is “ancient Mediterranean studies.”

Left out from the traditional Greco-Roman focus is not only potential African and Asian influences, but that other primary influence on European and early American institutions and culture: the Judeo-Christian biblical strand. That biblical influence can scarcely be a basis for “white supremacy” since Jesus himself and the writers of most of the New Testament (including the apostles Peter, John, Matthew, and Paul) and of the Old Testament were Middle Eastern Jews, and one of the main purveyors of this ancient civilization to the later world and the present, Augustine of Hippo, was born a fourth-century North African.

Editor’s note: The author is a former president of Covenant Theological Seminary in Creve Coeur, Missouri.

Malcolm Ryder ’76

4 Years AgoIntellectual Colonialism

I think the most brief, portable statement about the article and its subject should be that intellectual colonialism is a real thing; that colonialism is not the exclusive territory of peoples now identified as “white”; and that the relationship of power to certain cultures historically reflects distinctive capabilities that the given culture had and used. This combination of features should on no level be difficult nor unfamiliar to anyone who expects to hold an undergraduate degree from Princeton; and I don’t think it describes an existential crisis in what can be called “Classics.” Obviously, what merit there is to being able to distinguish something a “classic” versus “not classic” should be criteria immediately applicable beyond Greco-Roman history, and if it can’t or won’t be then that’s why the term “Classics” ought to go away. But the notion of “inherited intelligence” is pretty interesting, and why on earth would anyone want to dispense with that? The history and philosophy of science should always be complemented by the philosophy and science of history.

Michele Valerie Ronnick

4 Years AgoWilliam Sanders Scarborough’s Visits to Princeton

The photo featured on this flyer is a former slave named William Sanders Scarborough (1852-1926). He was not only a classicist affiliated for 44 years with the American Philological Association and the presenter of 24 papers at its meetings, but also the first Black member of the Modern Language Association. In 2000 I established this point in the millennial edition of the PMLA, and in 2001 Professor Eddie Glaude *97 was the first to win the book prize the MLA had set up in Scarborough’s honor.

In addition, Scarborough visited Princeton at least twice. In my edition, The Autobiography of William Sanders Scarborough: An American Journey from Slavery to Scholarship (2005), Scarborough describes stopping at Princeton in 1875 shortly after graduating from Oberlin to visit his friend, Matthew Anderson, at Princeton Theological Seminary:

“My arrival created some anxiety as well as curiosity on the part of Princeton officials. No negro had ever entered the college proper, though some were in its seminary . . . It was rumored that I had come to take post-graduate work in the college. I have often wondered what would have happened had I made the rumored attempt, but I was only reconnoitering.” (p. 56)

Sixteen years later he was back in Princeton to present a paper, “Bellerophon’s Letters,” at the meeting of American Philological Association held there in July 1891. (p. 115)

Thus with Scarborough as example in Princeton and beyond, there is significant history of Black engagement with classics prior to the 21st century, and the Alumni Weekly could have given at least a nodding reference to it through Princeton’s own history.

Editor’s note: The author is a distinguished service professor in the Department of Classical and Modern Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at Wayne State University.

Preston Kavanagh ’81

4 Years AgoWrestling With a Text

I take classics seriously and continue to think about the texts. I’m not sure the author has done the same. Below I present the reality of a classics education, ask if it innately oppresses other views, and address how the texts may have been repurposed. Greece and Rome were very different but remain worth close study.

I spent a lot of time in the classics department, and separately I spent six months studying in Rome and a post-graduate year in Athens. For the past 40 years I re-read Homer, Thucydides, et al., getting through at least one serious text each year. I continue to do what I did as an undergraduate — wrestle with the text and seek to understand both the author’s intent and the context in which it was written. I compare that to other majors and it’s not much different from many academic departments. I don’t see why the daily substance of a classics education deserves any particular opprobrium.

The next question seems to be whether a classics education, in and of itself, oppresses other views. That doesn’t fit my experience. The field allows a student to select from multiple distinct civilizations, and the history of interactions between them gets a lot of attention: Greeks and Romans were in awe of the Egyptians and the Persian empire. Carthage generated as much respect as fear. And it’s darn hard to be a Princeton classics student and somehow miss Byzantium, the Sanskrit texts underlying Hinduism, or medieval Islam. You see the sweep of history and gain a vocabulary for talking about events.

The last question seems to be whether Roman and Greek texts have been used to justify past sins of European powers. Well, of course, and it’s naïve to think we can apply texts without understanding them in context. High school Latin ends with the Aeneid, a great poem and a justification of Roman imperium. The political goals are obvious and discovering them was a great part of being 17. The Bible is commonly used to support someone’s agenda. It is still a worthwhile read, but I don’t endorse wandering in the desert. Celebrate the Iliad without endorsing the treatment of Briseis. Read widely, think deeply and you might end up getting educated.

Finally, I wonder if the author missed a big point. The study of Greece and Rome is of wildly different societies. We don’t model our society on the ancients — we compare and contrast, occasionally pulling out a good idea. (One worthwhile idea is to try to understand before judging. I apologize if I misunderstood the author’s intent. I ask that others tolerate my enthusiasm for the texts, many of which I encountered at Princeton.)