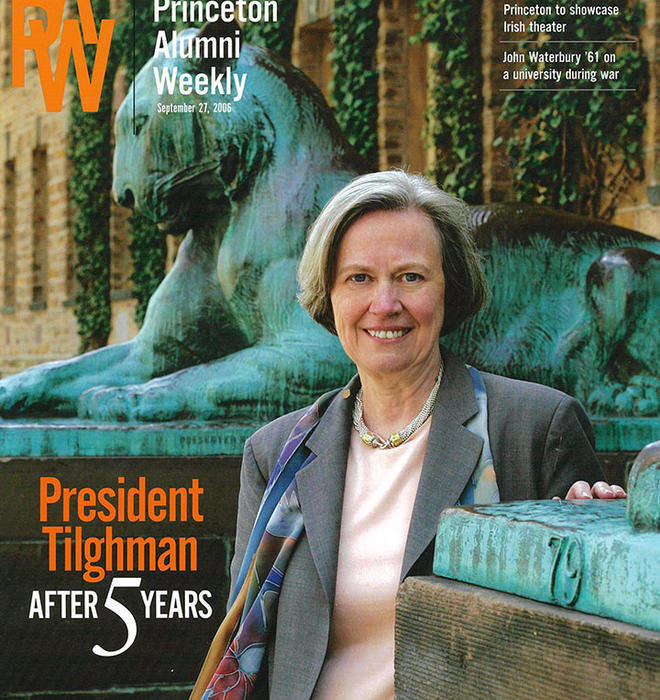

President Tilghman began her term as president under the media spotlight June 15, 2001, as Princeton’s first female chief executive, but the University barely blinked as she passed her fifth anniversary soon after the last academic year ended. Now beginning her sixth academic year as president, she sat down with PAW to discuss her most satisfying initiatives and difficult challenges, her pressure-filled first year, and her views on admissions and other issues in higher education.

She met with PAW’s Marilyn Marks *86 and W. Raymond Ollwerther ’71 in July; following are edited excerpts of their conversation.

In September, you begin your sixth academic year as president of Princeton. As you look back on your first five years, what do you see as the most important parts of your legacy?

The things that — for me — have been the most important are the new initiatives that have been realized in some cases, but also the new initiatives that are just beginning. Let me give you an example of something that I think has really come into fruition: the Lewis-Sigler Institute [for Integrative Genomics]. The success of the institute is really attributed to David Botstein and to his vision of how a research institute at Princeton University can have a profound effect on the curriculum. Not only do we have an absolutely brilliant building — which we do, thanks to Rafael Viñoly — and not only do we have a group of faculty who are really doing cutting-edge fundamental research, but we have a bonus, which is that we have probably the most exciting curricular innovation in science education anywhere in the United States.

Another area that we are one year from launching, but has dominated my first five years, is the four-year college preparation — preparation, most importantly, for the expansion of the undergraduate student body. Like genomics, that has involved creating a beautiful new space on campus. Whitman College is going to become an iconic place on the Princeton campus, and very quickly. But more importantly, it is launching another chapter in the history of residential life at Princeton. I think that none of us can really know how this is going to play out — how popular living in a four-year college is going to be for our juniors and seniors — but our goal continues to be to make it another choice, to give students for whom the current options are just not optimal another way of experiencing the residential aspects of their junior and senior years.

The other academic initiative that is constantly on my mind is the strategic plan of the engineering school. I’m delighted that [new dean] Vince Poor [*77] has such an important role to play in developing that plan and has embraced it, because it means the transition from Dean Klawe [Maria Klawe, who resigned last year to become president of Harvey Mudd College] to Dean Poor is, I think, going to be very, very fruitful. [There is] the neuroscience initiative, which I think is almost the perfect example of something that was identified as essential for a great university in the 21st century. We have already assembled a stellar faculty at both the junior and senior levels, and there will be more of that to come. Neuroscience is where genomics was in 1998, and it will require the same care and attention that genomics required in order to realize the potential that I think is there for Princeton to have a very important place in the very large field of neuroscience today.

And, of course, the creative and the performing arts is the last thing that I might mention — which is, in some ways, a dream come true for me. I grew up caring deeply about the arts, and I deeply believe that they are an essential ingredient of a liberal arts education. I believe that Princeton will be a substantially better place when the arts are more centrally located within our curriculum and campus life.

Peter Lewis ’55 gave $101 million for the arts. How did you convince him to do that?

He is inherently philanthropic — one of those individuals who understands the joy of creating something through generosity. So I didn’t need to convince Peter — what I did was to describe to him my vision for what I thought the creative arts could be at Princeton. And because he shared a passion, particularly for the visual arts, he responded very quickly.

[The process] was relatively short: a month, a couple of months ... and it involved a couple of dinners in New York. Peter had said on many occasions that he likes to enjoy his philanthropy, and he likes to give to institutions that he knows will use it wisely and create value, and value that he can see. Peter is a very big thinker, and what he responded to was the vision, as opposed to minute details about this, that, and the next thing. The details are not unimportant, I should emphasize, but it wasn’t the details that interested him, it was the vision.

You also oversaw Princeton’s move to end grade inflation. What’s your assessment of how that is working?

I think it’s safe to say that the students have been very skeptical about the value to them of grade deflation. That’s probably the understatement of the year. They’re concerned about it. Their concerns focus on the future, on their competitiveness for jobs, for graduate schools, for whatever they’re going to do next. We really have no evidence that their concerns are realized. In fact, I think we have evidence to the contrary. When we began to look at grade inflation at Princeton, one of the things that popped out immediately was that it was extremely inhomogeneous across the curriculum. There were departments where it happened, and there were departments that were grading virtually indistinguishably from the way that they were grading in 1975. So you can then do an experiment, and you can ask if the career options available to the students who concentrated in the non-grade-inflated departments were different over time than those who were in the grade-inflated departments, and the answer is no. I think what students don’t fully appreciate is the meaning of a degree from Princeton University.

The other thing I think [Dean of the College] Nancy Malkiel will tell you is that she has been vigilant in communicating our new policy to deans of admission at the primary [graduate] schools where our students apply, and they have been in large measure extremely grateful, because they were reaching a point at which grades were just meaningless.

Is there anything that you would do differently if you had a second chance?

Certainly, I would have preferred that the Web site event had not happened. [In April 2002, Princeton admissions staff members used the private information provided by Princeton applicants to gain unauthorized access to a Yale University admissions Web site. Yale notified Princeton officials about the activity in July 2002.] I was suddenly faced with a real crisis that did the thing that I would wish for least, which is to have Princeton represented in the press in an unflattering light. On balance, I think we handled that as well as we possibly could have handled it, but while it was being written about in the press, it was very unpleasant.

Shortly after I took office, Sept. 11 came, and I think it colored the first year of my time as president. It certainly changed the way in which students decided on courses: We saw this huge increase in the number of students who were taking courses in Near Eastern studies and politics. I think it was a call on the part of the students to try to understand this extremely traumatic event. So that was certainly a challenge that I wasn’t anticipating.

Something that I would do differently is the seven-week moratorium in athletics. [In 2002, the Ivy League presidents established a seven-week rest period for each sport, during which there would be no required athletic activities.] In hindsight, we should have anticipated some of the unintended consequences of that moratorium. And within a year the presidents faced up to the fact that we probably had acted precipitously, and we modified the moratorium. I think the motivation for the moratorium was the right motivation; I think the execution was less than ideal. And I could have been more effective in communicating to the student body, in particular, the reasons why the presidents had acted and what the implications of it were.

In your work with other college presidents, what do you find to be the most important issues?

The answer is different depending on whether they are select universities, whether they are private or public. For the Ivies, I think that the question remains access. That for me is the most important public policy issue in higher education. I think I wrote in my column [President’s Page in the Feb. 23, 2005, issue of PAW] that one of the most important public roles of a university like Princeton is to create social mobility. I think the challenge for universities like Princeton is the connection that exists between academic achievement and family income. And each one of us [Ivy presidents] is committed to trying to do different things that will help level the playing field — such as PUPP [Princeton University Preparatory Program], our homegrown program that has been very successful over the last five years in creating opportunities for local students. We are now much more aggressive than we were five to 10 years ago in reaching out to schools where there are very, very talented and gifted students who have never even dreamed that Princeton University might be an option for them. We have a lot of work to do to overcome the stereotypes in the popular media that all of us in this Ivy subcategory are places where the privileged go to university.

‘Tell us about yourself’

Hoping to glean every last bit of insight into prospective students, the Office of Admission asks these questions of applicants. PAW asked them of President Tilghman.

Favorite book: Vanity Fair (1917) by William M. Thackeray

Favorite recording: Highway 61 Revisited (1965) by Bob Dylan

Favorite movie: All About Eve (1950)

Favorite source of news: The New York Times

Favorite keepsake: Her children’s childhood photographs

Favorite source of inspiration: Bruce Alberts [biochemist, former president of the National Academy of Sciences] and Harold Varmus [Nobel laureate for studies of the genetic basis of cancer, president of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center]

Two adjectives your friends would use to describe you: “Determined” or “focused,” and “warm”

PAW asked an additional question: Favorite Princeton architect: “I would have to say Rafael Viñoly, because he’s the one I know the best, and I think that the stadium and the Icahn lab are two of the most wonderful buildings that have been built on the campus in the last 25 years.”

Doing things like the Princeton Prize in Race Relations is another instance — a way of reaching out to high school students and saying that Princeton is a place that cares about race relations. This university must be the place that creates opportunity for all gifted students, and not just ones who are lucky enough to be born into a family with means.

What else do presidents worry about?

Number one, which applies to all of us, is the worry that the social contract between the federal government and research universities over the funding of fundamental research is fraying — that the costs of research are increasingly being put on the shoulders of the universities, and very few of us can afford to assume those costs. Norm Augustine [’57 *59] wrote a very important study, Rising Above the Gathering Storm, that nailed what the future of this country will look like if we do not continue to support research in our major universities. With the demise of Bell Labs, we’re all that’s left standing. If it’s not universities conducting research, there’s nobody else.

The other is an issue that is really on the minds of all the public universities — the lack of public support for the great public universities, and the degree to which they are, for all intents and purposes, becoming privatized. I think it’s a looming crisis for public education, because when those universities become privatized, they are going to have to raise tuition. And because they have no endowments to use to subsidize financial aid for those who cannot afford it, they are going to become your worst nightmare of a private university, which is a university dependent on tuition to stay afloat.

Access and admission

You mentioned your concern about access for lower-income students. With the University beginning to admit larger classes, will it use some of the extra spaces for these students?

We are doing that, but we’re not doing it in a numerical and quota way. It’s been said many times that the admissions process at a university like Princeton is a highly individualized and nuanced process, where the wonderful admissions officers that [Dean of Admission] Janet Rapeleye has assembled look at the entire person. One of the things they look at is whether that individual has overcome some kind of adversity, and so it counts. But it doesn’t count in that they’ve got a number of slots and they’re going to fill those slots. I think that’s a wrong way of going about it, the wrong way to think about it.

The Chronicle of Higher Education each year ranks colleges according to the number of enrolled students who have Pell grants (for low-income students). Princeton is not only at the bottom of the Ivies, but virtually at the bottom of the 59 wealthiest private schools. How do you view that?

According to Robin Moscato, our new director of financial aid, the number of Pell grant recipients at Princeton is rising because of the changes we made in financial aid in 2001, but it will take time before those changes are well understood by the lowest-income students, who are Pell-eligible. We need to do a much better job at advertising the fact that our financial aid not only benefits students while they are here, but provides an additional benefit once they graduate with either no debt or, if they choose to take out loans for extras, with the lowest indebtedness in our peer group.

Will there be any changes in admissions, or the students being recruited, because of the larger classes?

The Wythes Report [approving the larger student body] was clear about only one priority for these 125 students, and that is it would not increase the number of recruited athletes. And that makes perfect sense, because the number of recruited athletes at Princeton is approximately comparable to the other seven Ivies. Teams don’t get bigger because you have more students, and so that is the one category where there will be no increase.

After that, we know that the pool that we get is deep enough that the extra 125 students are going to be indistinguishable from the 1,175 who are currently being admitted. Clearly, with the creative arts initiative, we anticipate that there will be more applicants who have interests in the creative and performing arts. We would like to get the number of engineers up to 20 percent. It has been under that for some time now, and given that roughly 20 percent of the University faculty resources are dedicated to engineering, we would like to have that many students. Our financial aid changes for international students have radically improved the quality of the international applicant pool, so I would anticipate more international students. So I don’t think there is a single answer to that question. We are looking in lots of different places, but I haven’t told Janet Rapelye, “We want 50 more of this and five more of this ... .”

Soon after you became president, you said in an interview that you wished Princeton could “begin to attract students with green hair.” What did you mean, exactly, and do you regret saying it?

No, I don’t regret saying it. What I was really referring to is that one of the powerful aspects of a Princeton education is the opportunity to live for four years with students who are utterly unlike yourself. Universities get typecast in high school — all over the world now — so that “Princeton likes this kind of student, Harvard likes this kind of student,” and so on. I think all of us believe that these stereotypes homogenize our student body in a way that admission offices have a hard time fighting against. And I think that having more students who weren’t the obvious Princeton candidates would be a very good thing for the undergraduate student body, because it would give students more opportunities to encounter students with different world views.

Has there been a change?

The faculty tell me yes, and they probably see it in the classroom. They are seeing a greater breadth of intellectual interests than what they were seeing in the past. I think we are getting a broader cross-section of students today, and we think that’s good educationally.

There seems to be a sense that while in the past Princeton looked for very well-balanced students, now Princeton wants a well- balanced class, with different students who are exceptional in different things.

Both [former admission dean] Fred Hargadon and Janet Rapelye have said to me that this is a misrepresentation of what an admission department thinks about and what they face. Because the pool of applicants is so strong, you don’t have to make these kinds of apparently distinctive choices. You can have someone who is an absolutely stellar mathematician, but is much more than that.

Eating Clubs

One thing related to both the four-year colleges and admissions is the eating-club system. There is a concern that more of the clubs will have to close. How important are the clubs at Princeton, and how do you see that relationship between the University and the clubs going forward?

I think the clubs have the potential to be a very positive part of the social life at Princeton University. They provide opportunities for students to have parties, to have a social life that is safe — they’re not getting into cars — and where they can congregate with their friends. And if the eating clubs did not exist, we would have to create such spaces because they are absolutely essential for college life. So at no point have we ever entertained an idea that we would do away with the eating clubs.

The issue is the impact, particularly of the bicker clubs, on the social milieu of this University and the perception of the University outside Princeton, N.J. The eating clubs loom at Princeton in ways that the secret-society clubs at Yale or the finals clubs at Harvard do not because we don’t have a lot of alternatives for feeding juniors and seniors, and so the students don’t have a free choice to join the clubs in the way they do at Yale and Harvard. In a way, you’re devising your way to eat as a junior and a senior, and that makes the clubs loom larger. When you’re 18 years old and you’re thinking, “How am I going to find my place at my alma mater?” I think the idea of having to go through a bicker process that every year leads to unhappiness, that separates friends from friends, that causes real pain and suffering, is problematic. We have to acknowledge it, face up to it, and think about how we could, over time, modify the system so that we retain all of the positives that come from the presence of the eating clubs — which are substantial — but reduce the downside of the eating clubs.

It seems that this would require changes on both sides.

I think so, and I think it will take a recognition by both students and alumni that there are negative impacts of the eating clubs. This is the single most common reason why [an accepted applicant] turns Princeton down.

There’s also the question of students who feel that they can’t afford to eat at the eating clubs. Is the issue of financial assistance on the table?

That issue is still on the table, and it is part of the series of discussions that [Executive Vice President] Mark Burstein is having with all 10 clubs. It will be resolved one way or another in this academic year.

One vision that might be worth thinking about is that all students live in four-year residential colleges and all students have a membership in one of the eating clubs. That might be a scenario that we could strive for down the line. We are asking the clubs to consider joint memberships so that a student can both live in a four-year college and be a member of an eating club, and have some of their meals in the club, and some of their meals in the college.

How’s it going over?

More positively with some clubs than others. Every club is an independent actor and will have its own attitude toward such a proposal.

Robertson lawsuit; fundraising

The Robertson lawsuit has required a lot of your time recently. Many people think that the public airing of ill will has given each side a black eye. How did it get to this point?

It is obviously very difficult to know what is in the minds of the plaintiffs in this case, but had we perceived that there was an opportunity at any point in the past four years to settle this case, we would have embraced the idea. There is nothing to be gained from having this case drag on and on and on.

Has it had an impact on relations with alumni, including alumni giving?

No. I don’t think it’s had any impact whatsoever. In fact, we’re about to announce this week that we broke the AG record this year again [see Notebook, p. 17].

Has the case spurred Princeton to develop guidelines that clarify donor intent so alumni are assured that the money is used as they desire?

Not only do we have guidelines, but the guidelines have been in place for many, many years, and they guide development in every single conversation that we have with the donor. The terms of the gift are laid out in a document that every donor reviews and modifies. And those terms we respect and take seriously, and I would posit that we have done so brilliantly with the Robertson Foundation. We have built up one of the finest schools of public policy and international affairs in the world, and have done so respecting the terms of the gift.

As Princeton gears up for its next major fundraising campaign, there has been talk in general circles about universities with big endowments. People ask, “How much money do they really need?” How do you make a case that universities with such sizable endowments need more?

I think you have to ask yourself what are we using the endowment for. The first thing is access. If you look at how the universities with the largest endowments spent the wealth that was created in the late 1990s during the dot-com bubble, only Princeton really plowed the majority of that gain into financial aid by the elimination of loans. Lots of universities built new buildings, hired new faculty, and did all those kinds of wonderful things, but what we did is make a historic commitment to the elimination of loans. So if you ask me, what does giving to Princeton mean, it means that we will continue to provide access for gifted students, whether they can afford to pay for their education or not.

The second thing that we do is we provide a highly individualized kind of education where students encounter senior faculty all the time. We have a student-faculty ratio that’s under 6:1; there’s no other major research university in the country that comes even close to that number. That’s on purpose. So when people say, “Couldn’t Princeton cut costs?” I say, “Sure, tomorrow I could eliminate the freshman seminar program. That would save us a lot of money.” But what would it mean? It would mean that two-thirds of our freshmen who now can sit around a table with a faculty member will be in McCosh 50 instead.

The third thing I would say is that if we are to do new things, we must raise new resources, because otherwise something will have to go. When we committed ourselves to neuroscience, we didn’t cancel the classics department, right? Neuroscience is an add-on, and when you have an add-on, the resources have to come from somewhere. So I think the major reason that we embark on these campaigns every decade or so is because we are never satisfied with where we are, and we are always looking over the hill to the next way to make this an even more effective educational institution.

You’ve talked about major initiatives. Are there other important things that are not as well known but will be moving forward in the next five years?

Something that we haven’t talked about but which is, for me, extremely important is increasing the diversity of the faculty and the staff — both in terms of gender and in terms of ethnicity. In the words of Arthur Miller, “Attention must be paid,” and that attention has to be pretty unrelenting. If you stop paying attention to this issue you get backsliding, and it happens with extraordinary rapidity. So a lot of the things that we have been doing through the Health and Well-Being Task Force are designed to make Princeton more family-friendly.

We are continuing to think creatively about how we can increase the number of underrepresented minorities in our graduate school, because one of the things we know is that if you look at where Latinos and African-Americans are going to graduate school, they are not schools that we normally recruit from [for faculty positions], which means that we’ve got to be training them ourselves. As a national service, we have to get more underrepresented minorities interested in academic careers. The fact that the number of underrepresented minority students who will enroll in our Ph.D. programs this year increased by more than 50% is really stunning, and it is definitely the result of paying attention.

What made the difference?

I think communicating with other universities where we are likely to find prospective graduate students, and that is often, ironically, in small liberal arts colleges. The statistics show that many future academics come out of these small liberal arts colleges — including high-quality historically black colleges like Howard and Morehouse and Spelman. And you can’t just admit students, you have to then create a very positive educational opportunity here, or else they will leave. Closing thoughts

You are on Google’s board of directors, just as many educators and university presidents are on corporate boards. There are times when corporate interests are not necessarily the same as a university’s values. When there are differences, how do you approach them?

I think you talk about it. There are actually two university presidents on the Google board. John Hennessy [Stanford] is the other one. John and I tend to think very similarly about most issues, and I think that were an issue to come up with Google where we felt as though the company’s very strong commitment to ethical behavior was being compromised in some way or was going to have a really negative effect on universities, John and I would feel extremely comfortable in talking about it and speaking up.

There was a lot of interest in the media about what was happening with Google in China. [In January, Google launched Google.cn, a Web site for China that removed some information from the search results. The standard Google Web site continued to exist in China, though it was slow and difficult to access.] Universities are committed to the free exchange of information. Was there discussion about that?

Absolutely, there was a lot of discussion about that, and a lot of weighing of the options. I think fair minds could disagree about what Google ultimately decided to do. I thought what it did made a great deal of sense in that it left up both sites: You as a user could choose whether you wanted to use the site that you knew perfectly well was being censored, but where you would be able to get quick search results, or you could use the U.S. site where the censorship was less effective, but which was going to be very, very slow. Google never pretended that the Chinese site was anything but a censored site; it was there on the Web site for everybody to see. What it was providing was choice for the Chinese, and at the end of the day I felt comfortable with that.

Since you’ve become president, is there anything that you miss about being “just a professor?”

I miss my colleagues. Science has a bad reputation for being a very reclusive, solitary, lonely kind of profession. Whenever a student told me they were going to medical school [instead of becoming a scientist] because they liked to work with people, I would just howl with laughter because science is a very interactive profession, and I, over many years in the profession, developed deep, deep friendships ... not just with my colleagues here at Princeton, but my colleagues all over the world. I’ve been distanced from them in the last five years and I really miss them. I still read Nature and Science, and every once in a while I read a paper and think, “Oh, it’s such a good experiment!” And I can feel the juices start to boil in me, because the thing I like best is designing new experiments. So that’s a momentary twinge, but I enjoy what I’m doing now so much that there isn’t time or the inclination for regret.

No responses yet