The Day That Changed Everything

Seventy-five years ago, Pearl Harbor transformed the life of every student — and the University itself

Early in the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, Francis Bell ’37, a sailor on the destroyer Phelps at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, was awakened by the sound of machine-gun fire. He looked out his porthole and saw Japanese warplanes rocket by. Not far away, on the U.S.S. Farragut, Jim Benham ’39 “froze at the incredible sight,” he later recalled, and was looking at the battleship Arizona “when it blew sky-high.”

It’s been 75 years since the attack that killed 2,403 Americans and plunged the nation into the Second World War. The impact of that day was especially great on college campuses, crowded with draft-age men. This is the story of how Princeton University responded to Pearl Harbor — and was transformed by it — as recorded in the archives and as remembered by a handful of living alumni who were there.

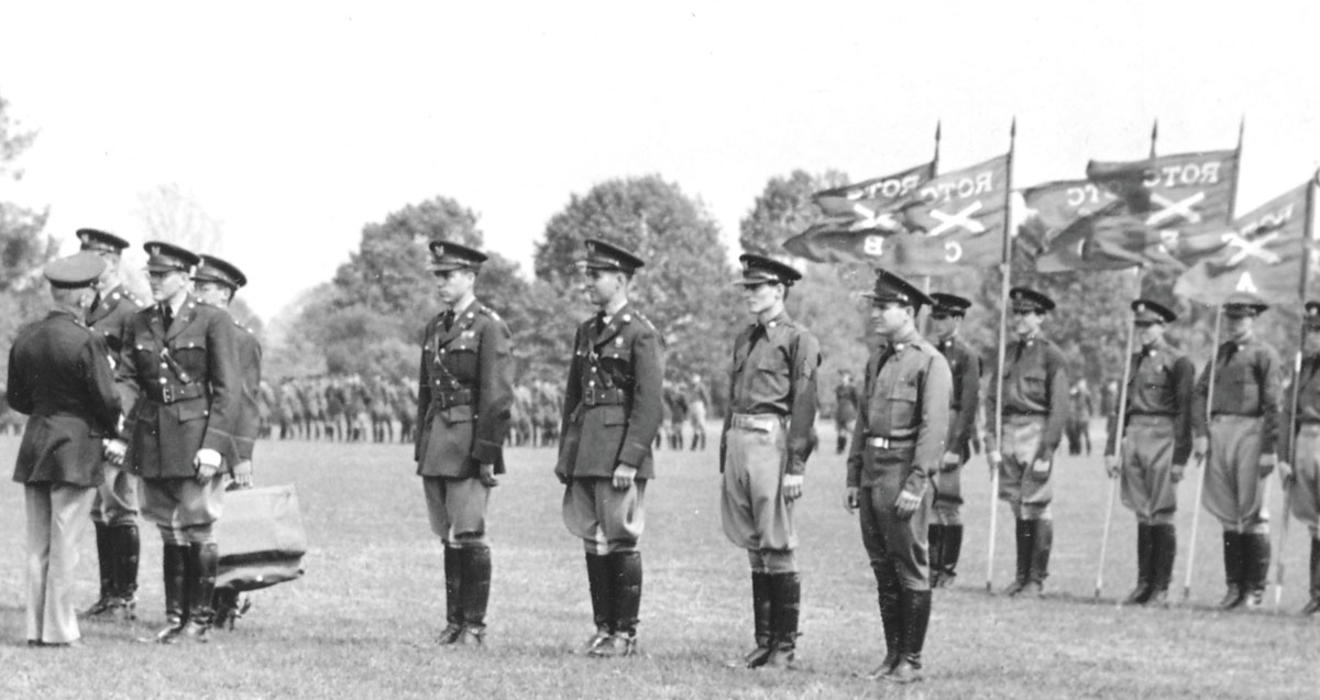

Above, as about 1,000 people watched, 800 Princeton ROTC students took part in Regimental Day exercises in May 1942.

When 2,432 undergraduates started the school year in September 1941, Princeton had largely bounced back from the Depression and welcomed its biggest freshman class ever, the Class of ’45. Students looked forward to the timeworn rituals of collegiate life: puffing pipes while kicking yellow leaves scattered along McCosh Walk, sandwiches at the “Balt,” bicker, and houseparties.

Nothing ever really changed at Princeton, it seemed, except for the marquee at the Playhouse Theater, then showing Citizen Kane, and the hoisting of additional bells to the Gothic tower at the Graduate College. Under the elms, all was placid: The only strife was whether to lower the cost of eating-club memberships or whether faded Prospect House should be demolished to make room for a new library. “It was the last hour of a golden era,” John Kauffmann ’45 later recalled. “We did not know that at the time.”

Yet it was impossible to ignore entirely the distant rumblings of war. German tanks were overrunning the Soviet Union as Royal Air Force bombs hit Berlin. Many alumni were already in the armed forces — 754 of them by Christmastime — and ROTC enrollment jumped by 200, to 825. Princeton’s soft-spoken president, Harold Dodds *1914, constantly warned that America wasn’t doing enough to counter the Nazi threat.

In his address in the Chapel at Opening Exercises Sept. 21, Dodds set aside the usual script about campus goings-on and called on the country “to marshal the full strength of our national power against a totalitarian Axis” that, intent on driving democracy to worldwide extinction, threatened American civilization.

Sunday morning, Dec. 7, was quiet as usual in Princeton. Episcopal services were held in the Chapel at 9:30, followed by the Divine Service at 11, where a Yale divinity professor intoned the sermon and newspapers rustled in the balcony. Three hundred from town and gown made plans to attend a concert of medieval music at Procter Hall that afternoon.

At about 2:30 p.m., a news broadcast broke into the dance music that was playing at Tiger Inn, where everyone looked at one another and asked: Where — and what — is Pearl Harbor? Radios were tilted out of dormitory windows so others could hear the news. “We were speechlessly confounded,” recalled Kauffmann, who died two years ago, “and put down the funny papers.”

The news was perhaps most personal to Ned Kimmel ’42, interrupted in his room while studying: He caught the first train for Los Angeles. His father was commander-in-chief of the Pacific Fleet, wrongly reported to have been killed. Instead, the admiral lived to see himself relieved of his command for having failed to predict the surprise attack — which many now believe was unfair. Ned Kimmel would spend much of his long life campaigning to have Congress rectify what he deemed a great injustice.

After sunset that day, 500 undergraduates ransacked the town to build a mammoth bonfire in the quad in front of Pyne Hall dormitory. They grabbed wooden bike racks and the ticket booth from the gym; mattresses, desks, banisters, and doors were tossed from Pyne windows. As the fire mounted, students shouted, “Let’s go to war!” and set off firecrackers. Proctors ran in to break up the rally, but smaller fires erupted at Holder and by the train station.

By the next day, Monday, Dodds had issued a patriotic statement from Nassau Hall (“Since 1746 Princeton University has never been found wanting”) but urged students not to pack their bags to go fight right away, because the nation needed college-trained men, now more than ever.

Instant steps were taken to protect the scientific facilities of the campus, lest they be sabotaged: Undergraduates guarded Frick and Palmer labs, where the Manhattan Project would get underway months later. Many feared that German bombers would follow the railroad line outside Princeton, targeting New York or Philadelphia. Air-raid spotting posts were set up around town, and within four days 80 students volunteered.

READ MORE: “Princeton Faces the War,” from PAW’s Dec. 12, 1941, issue

As America faced yet another world war, the student body was reeling from the suddenness of events. “Pearl Harbor threw the campus into a disarray that is still vivid to me,” William Zinsser ’44, the master writer, editor, and teacher, recalled years later. “Our tidy plans had come apart overnight; the education that only yesterday had seemed so important suddenly seemed like a frill.”

“It made me think, ‘What do you do?’” remembers Robert Whittlesey ’43, whose father was a professor and who had grown up right behind Elm Club. “Can I finish my degree before I join the Army?” Everyone was asking the same things: How much longer would college normalcy last? Would the student body quickly evaporate and the campus be transformed into a military encampment, as had happened, controversially, in World War I?

The shock and treachery of the Japanese attack were, in a sense, a blessing for morale: They swept away all doubts about right and wrong. Nearly everyone was bellicose now, ready to do his duty. “I was an America Firster and kind of a pacifist, trying to keep us out of the war,” remembers Whittlesey. But Pearl Harbor changed everything: “Now I was totally sold. And I don’t recall talking to anybody who was anti-war.” Charlie Crandall ’42, who had marched on campus for isolationism in 1940, was now “angrier than a wet hen — I wanted to fight!”

All this marked a dramatic shift in student opinion, “like a magic wand had hit,” Crandall says. “I never saw such a turnaround in my life.” Raised during the Depression and a general spirit of debunking, undergraduates of this era were a cynical crowd, and the Classes of 1943 and ’44 had, with black humor, voted Hitler “Greatest Living Person.” A year before Pearl Harbor, a petition to keep the United States out of war was circulated in the Commons dining halls and quickly garnered 300 signatures. But all that was forgotten now.

BY SUMMER 1942, six months after Pearl Harbor, the war was fully underway: 2,251 Princeton alumni were in the armed forces, including nine pairs of fathers and sons.

What did World War II mean for the University itself? Eight days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Dodds called a rare mass meeting of the undergraduates (the first since the automobile ban of 1926) in Alexander Hall. It was so crowded that some stood shivering in the dark outside, listening to a loudspeaker. The walls trembled to the singing of the national anthem and “Old Nassau,” but the silence was profound as Dodds began his remarks from the rostrum where Woodrow Wilson 1879 had once spoken of “Princeton in the Nation’s Service” — Wilson, who had so famously warned of the danger of another world war.

Dodds outlined fundamental changes in the curriculum, aimed at threading the needle between too much military-focused education and too little. There would be no mandatory-for-all uniforms and marching this time. He called upon students to take a long view — “it may be your duty not to do the exciting and spectacular thing at the moment,” but rather to remain in the classroom, in order to meet the country’s urgent need for officers. He ended with a ringing prediction: “There will always be an America. ... There will always be a Princeton.”

In this speech, Dodds rebutted the argument — urged by some parents and older brothers — that patriotic duty meant joining the military right away. Newspapers praised the quickness with which he had reshaped the University. “How he pierced the bureaucratic haze so swiftly I can’t imagine,” Zinsser wrote in The New York Times in 1981. “He seemed to be the only college president who had organized his troops at all,” and thus he “reached a high peak of leadership that night.”

Under Dodds, 195-year-old Princeton changed direction instantly, just days after war was declared. An “accelerated” program was instituted, which 70 percent of students chose to take: Reading period was canceled, and there would be summer school. Twenty-seven war-related courses were established, including gunnery, navigation, and language instruction in Japanese and Russian. Select students entered the Navy V-7 training program. Herb Hobler ’44 recalls that his Spanish “gut course” suddenly became much harder, as Dodds announced that English would no longer be spoken at all in foreign-language classrooms.

LISTEN to Herb Hobler ’44’s memories of 1941 on the PAW Tracks podcast

The great new thrust was in the sciences, and an aeronautical engineering department was founded. But eschewing the “armed camp” approach of World War I, humanities courses remained on the books, a patriotic program in American civilization was instituted, and senior theses were still required. Dodds would tell alumni and parents in the gym on Alumni Day that students should not accelerate too quickly — he hoped to give all of them at least two full years of Princeton courses. But for most, this was not to be.

When Tigers returned for spring semester in 1942, the war seemed ever closer to the snowbound campus. In January, news arrived that a member of the Class of 1938 had been killed serving with the Canadian Air Force over Germany. The drumbeat of the draft was sounding ever louder; exemptions were fewer, and some students vanished suddenly from classrooms. By February, so did a dozen faculty. That month, Crandall found himself standing naked in a line of draftees in his hometown high school, undergoing a medical inspection. It was a line that would lead, for this Princeton senior, to Iwo Jima and beyond.

SEPTEMBER 1942: Undersecretary of the Navy James Forrestal 1915 spoke at the unfurling of the Service Flag over the doorway of Nassau Hall, with 16 stars for Princetonians who had already died.

As Yale covered its buildings in sandbags, the Princeton Art Museum removed some of its treasures to basement storage. Students practiced air-raid drills and were told not to run to landmarks like Alexander Hall or the Chapel if Nazi bombers appeared. All this did not seem entirely absurd: In February, an oil tanker was torpedoed off New Jersey by the German submarine U-578. After the Pearl Harbor surprise, anything seemed possible. On the jittery West Coast, the head of Defense Command, Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt 1900, recommended to President Franklin Roosevelt that all Japanese-Americans be rounded up as a precaution.

By summer 1942, six months after Pearl Harbor, the war was fully underway: 2,251 Princeton alumni were in the armed forces, including nine pairs of fathers and sons. Summer school, once reserved for the academically inept, was required for all “accellerees,” and 1,700 students endured the heat and humidity of the first regular summer term in 98 years. (A summer session was offered in 1918, but only 75 students enrolled.)

Everything seemed strange: walking to class in shorts, to disapproving stares from local matrons. A combat training platoon that “attacked” the town, dressed as Luftwaffe parachutists. Bumbling ROTC maneuvers in local woods that gave everyone poison ivy. Ancient traditions suddenly were tossed out — early-arriving freshmen dared to appear without the customary hats called “dinks” and strolled right in front of Nassau Hall. Most unimaginable of all: The 23 students who arrived to study mapmaking all wore skirts.

In September 1942, with a new school year starting, Undersecretary of the Navy James Forrestal 1915 spoke at the unfurling of the Service Flag over the doorway of Nassau Hall, with 16 stars for Princetonians who had already died. As Dodds listened gravely, Forrestal alluded to Wilson’s dream of world peace, so brutally shattered. All knew the war was going badly.

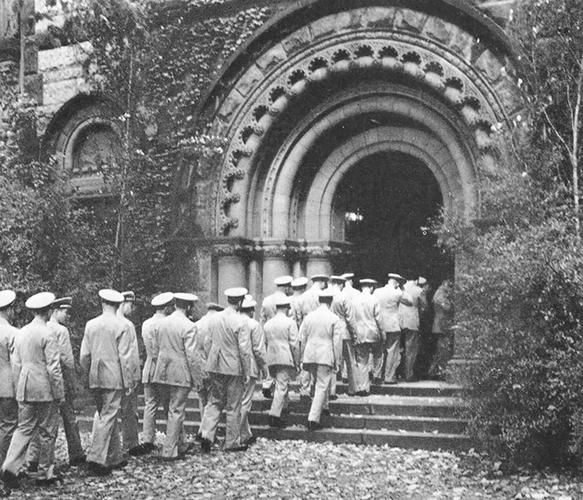

The University was struggling now, running a deficit of $850,000 as students withdrew in masses (according to one rumor, Princeton was readying to close its doors before Christmas). Affiliation with the federal government seemed imperative, so a Navy Training School moved into campus dormitories. In time its ranks would include the first black students to attend the University in modern times — three graduated in 1947.

FALL 1942: The University was struggling now, running a deficit of $850,000 as students withdrew in masses. Affiliation with the federal government seemed imperative, so a Navy Training School moved into campus dormitories.

Dodds knew that the “armed camp” was now unavoidable. The shortage of officers foreseen in 1941 had been eclipsed by the urgent need for 10 million soldiers. In a second mass meeting, he was frank: “One thing can be stated without sugar coating, and that is that all able-bodied students are destined for the armed services.” That fall of 1942, the draft age was lowered to 18, and, Kauffmann recalled, “the bottom dropped out.”

A year and a month after Pearl Harbor, its full implications for the undergraduates were clear. Those who remained from the Class of 1943 graduated months early, in an unprecedented scene amid the snows of January. “Tomorrow, we will be years older,” class historian Alexander Fowler told them. John Boyd ’43 was among the many dozens who missed his college graduation, but his case was tragic: He had not survived the Battle of Guadalcanal.

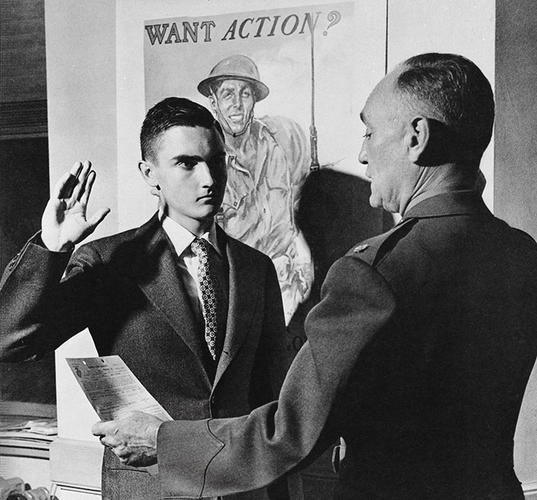

Now throngs of students were called up weekly, including Hobler, who got a letter in February 1943 telling him to report to Trenton to be sworn into the Army Air Corps. The charms of Princeton seemed far away, he recalls, as he was sent to march up and down the Atlantic City Boardwalk in biting cold — “anything to make me feel inferior.” This student who had heard the news of Pearl Harbor on his parents’ car radio, driving the Great Road into Princeton, would go on to fly 10 missions over Japan, including four firebombing raids on Tokyo.

Long gone was the cozy campus dimly remembered from the golden fall of 1941. Pearl Harbor had, in fact, changed everything, from adopting the more rigorous and scientific curriculum, to blending Princeton’s mission with Uncle Sam’s, to opening the door a crack to blacks and women. All these changes eventually would prove revolutionary, post-war.

Every Princeton student had been thrown into academic and personal turmoil by the events of Dec. 7, 1941 — profoundly so. Only a dozen of the 692 undergraduates in the Class of 1945, for example, were left on campus by senior spring. Instead of merrily imbibing at the “Nass” or lounging on the sofas of Prospect Avenue, as seniors had always done, these Princetonians were strewn across the globe, suffering in tents and barracks and foxholes, “lost in the great snarling mass of war,” one recalled in a 1952 reunion book.

Many would return to study after V-J Day, but ’45 remained fragmented, in common with other wartime classes. Forty-five’s graduations stretched across many years: The first accellerees got out in February 1944, but the last to graduate received diplomas in 1950, just in time to attend their fifth class reunion.

One ’45 classmate who came back to the University after the war was Warren Eginton, who had helped liberate Manila by tank and narrowly survived being shot in the chest. Now 93 and a federal judge, he has never forgotten his reaction to hearing the news of Pearl Harbor while playing ping-pong in Tower Club, in December of his freshman fall: “It was the same as I felt on 9/11: ‘Well, the world just changed.’”

W. Barksdale Maynard ’88 is the author of seven books, including Princeton: America’s Campus and The Brandywine: An Intimate Portrait.

TALK BACK

For Christmas 1943, the University sent each of the 1,300 Princetonians then in the military three books each serviceman chose from a list (see below).

If Princeton did the same thing today, which books would you propose as options?

The Education of Henry Adams Adams

American Short Stories of the 19th Century

Confessions St. Augustine

In the Midst of Life Bierce

Lavengro Borrow

The Thirty-Nine Steps Buchan

The Pilgrim’s Progress Bunyan

Collected Stories Lewis Carroll

The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini

Don Quixote Cervantes

Abraham Lincoln Lord Charnwood

The Moonstone Collins

Comprehensive Anthology of American Verse

Lord Jim Conrad

The Enormous Room cummings

The Origin of Species Darwin

The Pickwick Papers Dickens

Crime and Punishment Dostoyevsky

The Three Musketeers Dumas

The Nature of the Physical World Eddington

How Russia Prepared Edelman

Elizabethan Playwrights

English Verse (Vol. III)

English Verse (Vol. IV)

A Passage to India Forster

Fourteen Great Detective Stories

Penguin Island France

The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

Great Modern Short Stories

The Making of the Earth Gregory

A Farewell to Arms Hemingway

The Odyssey Homer

The Purple Land Hudson

Toilers of the Sea Hugo

Man’s Place in Nature, and Other Essays Thomas Huxley

The Varieties of Religious Experience William James

Man; A History of the Human Body Keith

Collected Short Stories Lardner

Arrowsmith Sinclair Lewis

Of Human Bondage Maugham

Moby Dick Melville

Essays Montaigne

Pocket History of the United States Nevins and Commager

Mutiny on the Bounty Nordhoff and Hall

The Conspiracy of Pontiac Parkman

Pensees and The Provincial Letters Pascal

The Grammar of Science Pearson

An Outline of European Architecture Pevsner

The Philosophy of Plato

Pocket Book of Verse

Shakespeare: the Complete Works (Vol. I)

Shakespeare: the Complete Works (Vol. II)

Shakespeare: the Complete Works (Vol. III)

The Seven Plays Sophocles

Tortilla Flat Steinbeck

The Red and the Black Stendhal

Treasure Island and Kidnapped Stevenson

Eminent Victorians Strachey

Christianity and the Social Order Temple

Henry Esmond Thackery

Walden Thoreau

History of the Peloponnesian War Thucydides

Anna Karenina Tolstoy

War and Peace Tolstoy

Fathers and Sons Turgenev

An Introduction to Mathematics Whitehead

The Journal, and Other Papers Wollman

2 Responses

Frankie Leung

9 Years AgoInteresting part of the...

Interesting part of the history. Reminds me of Harvard abolishing ROTC during the Vietnam War era and the following years.

Charles S. Johnson ’48

9 Years AgoV-12 Units’ Role in Sports

In “The Day That Changed Everything” (feature, Dec. 7), I was disappointed that you failed to acknowledge the existence of the Navy and Marine Corps V-12 units at Princeton, especially from 1945 through June 1946, when they were dissolved. These units were a major proportion of the entire student body at Princeton. They comprised many combat veterans who were in the program to fuel the need for officers in the expected invasion of Japan.

They were the backbone of all the sport teams at that time. Princeton returned to football in the fall of 1945. The entire starting lineup and backups were all members of these programs.

Charlie Caldwell ’25 was recruited as head coach, with Dick Colman, Jud Timm, and Wes Fesler as assistants. A little-known fact was that Charlie installed the “T” formation that year, before converting to his beloved single wing in 1946. Although an unknown talent at the time, we upset nationally ranked Cornell at its home field led by All-American quarterback Allen Dekdebrun, later with the Buffalo Bisons.

In 1946, many of these same players were participants in the 17–14 upset of the University of Pennsylvania’s team, ranked third nationally, before a sellout crowd at Franklin Field.

Special recognition should go to three of our players: Tom Finical ’47, Ernie Ransome ’47, and Neil Zundel ’48, all from the V-12 program.