Einstein at Princeton

A century ago, the world’s best-known scientist brought his relativity theory to McCosh

May 9, 1921: Albert Einstein, the most famous scientist in the world, stood on stage in McCosh 50, Princeton University’s largest lecture hall.

He wore a black cloak, creased trousers, and a green knitted tie, and drew imaginary lines with chalk as he addressed his audience, according to the Evening Bulletin of Philadelphia: “The long hair that ended in tight curls and the chalk balanced between his fingers like a baton gave him the appearance of an orchestra conductor.”

Earlier in the day, Princeton had awarded Einstein — age 42 — an honorary degree. President John Grier Hibben 1882 compared him to Pythagoras, Galileo, and Newton. Graduate School Dean Andrew Fleming West 1874 described Einstein as a Columbus “voyaging through strange seas of thought alone.” Now he would explain to the general public his astonishing, famously abstruse theory of relativity.

The room was packed. The 400 attendees included visiting scientists, curious members of the public, and reporters from major newspapers. They had come to see the man reputed to have overthrown Newton, rewritten the laws of physics, eradicated classical notions of time and space, accurately predicted the bizarre bending of starlight, and had done this with nothing more than the power of his mind.

“Ladies and gentlemen!” Einstein began. He immediately assured his audience that his lecture would have minimal mathematical elements. He then explained the concept of relative motion, something pondered by Galileo nearly 300 years earlier.

“The theory of relativity is so named because this whole theory is concerned with the question of the extent to which any motion is merely relative motion,” Einstein said. “For example, when we speak of a car moving in the street, the motion refers to the piece of ground or surface called the road and this piece of Earth’s surfaces plays the role of a body on which this motion will develop. Thus, the very idea of motion is relative motion, and according to the conception of motion one could equally well say the street moves relative to the car, as we can say the car moves relative to the street.”

Except he said all this in German. (His actual opening words: “Meine Damen und Herren!”)

This was the first of five Stafford Little Lectures he had agreed to give on successive days. The first two were “popular” lectures, followed by three of a more technical nature for scientists. A stenographer took notes in German in shorthand, and she handed these to a Princeton physics professor, Edwin Adams, who then summarized the lectures orally in English. (In 1921 an American physicist had no choice but to be fluent in German, since Germany was then the center of the physics world.)

Einstein’s audiences shrank as the days progressed, likely as people realized that his theories remained incomprehensible even in translation. By lecture three he was speaking in a small classroom, according to The Formative Years of Relativity: The History and Meaning of Einstein’s Princeton Lectures, by Hanoch Gutfreund and Jürgen Renn.

But the Gutfreund-Renn volume explains why the lectures were far more than a momentary status-enhancing chapter in Princeton history. The lectures, condensed from five to four, formed the basis for a book, The Meaning of Relativity, published by Princeton University Press in January 1923 and in print ever since, with Einstein adding appendices over the ensuing decades. Einstein had previously written a popular book on relativity, published in 1917. The Meaning of Relativity became one of the two canonical Einstein texts on relativity. According to Princeton historian Michael Gordin, the geometry used by Einstein to develop his theory was unfamiliar to many scientists at the time, and the new book helped them understand it.

Gutfreund and Renn write: “Neither before nor afterward did he offer a similarly comprehensive exposition that included not only the theory’s technical apparatus but also detailed explanations making his achievement accessible to readers with a certain mathematical knowledge but no prior familiarity with relativity theory.”

Einstein’s theory of relativity was not a singular construct but rather an elaborate edifice constructed over more than a decade. In his “miracle year” of 1905, when he produced an explosion of revolutionary insights, he produced what would later be called the Special Theory of Relativity. He explained that there is no master clock in the universe, nor fixed points in space. No longer could anyone say two events happened at the same time. Simultaneous according to whom?

Einstein’s universe was composed not of three dimensions but four — the fourth being time. He explained the concept of “time-space” in The Meaning of Relativity: “Upon giving up the hypothesis of the absolute character of time, particularly that of simultaneity, the four-dimensionality of the time-space concept was immediately recognized. It is neither the point in space, nor the instant in time, at which something happens that has physical reality, but only the event itself.”

Einstein said the reason experimentalists hadn’t been able to detect the effects of the ether assumed to permeate space was that it didn’t exist. The banishment of the ether hypothesis was a central feature of relativity, and it so happened that a report reached Einstein while he was at Princeton saying that an astronomer at Mount Wilson in California had, in fact, detected signs of the ether. That would have blown relativity theory to bits. Einstein was not perturbed: He knew he was right. He uttered a line that, when translated into English, became one of his most famous: “The Lord God is subtle, but malicious he is not.”

In 1915 he managed to produce the equations that extended his theory to explain gravity, in what he called the General Theory of Relativity. Gravity, Einstein said, reflected the curvature of space and time in the presence of matter. No longer was gravity a spooky force acting at a distance; it was built into the fabric of the cosmos.

Relativity captivated scientists immediately, but Einstein did not become a global celebrity until 1919. That was when an observation of a solar eclipse confirmed a key prediction of his theory of relativity: that starlight would be diverted by the curvature of space near a massive object like the sun. The confirmation was announced by the British physicist Arthur Eddington, who had organized an expedition to an island off the coast of West Africa to observe the eclipse. The resulting media sensation was orchestrated by Eddington, and The New York Times published a breathless headline: “LIGHTS ALL ASKEW IN THE HEAVENS: Men of Science More or Less Agog Over Results of Eclipse Observations.”

The world would remain agog in the months and years to come. There was just one major problem with Einstein’s theory: Few people could understand it.

Prior to Einstein’s Princeton appearance, The New York Daily News noted that 650 tickets to the lectures had been requested, and it ran the story under the cheeky headline “650 More People Would Understand Relativity.”

In 1921 the world was still recovering from the trauma and industrial-scale slaughter of The Great War, as it was then known. The planet had also just emerged from a pandemic that left many millions dead.

Daniel Okrent, a historian who has written extensively about the 1920s, tells PAW that the war “threw the world off its axis.” He points to a diary entry of Franklin Lane, the secretary of the interior, from January 1920:

“The whole world is skew-jee, awry, distorted and altogether perverse. The President is broken in body, and obstinate in spirit. Clemenceau is beaten for an office he did not want. Einstein has declared the law of gravitation outgrown and decadent. Drink, consoling friend of a Perturbed World, is shut off; and all goes merry as a dance in hell!”

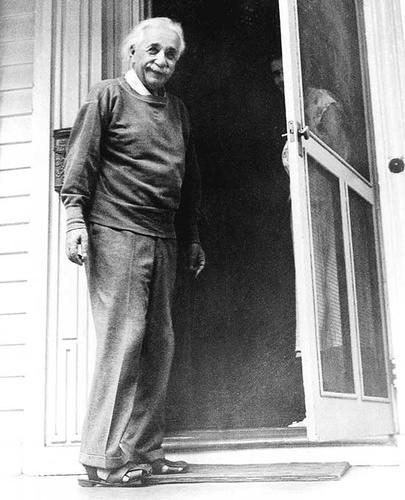

Einstein was a fascinating figure as he walked off the ship in New York carrying a pipe and a violin case. He was youthful still — not yet the rumpled, grandfatherly figure we know from T-shirts, posters, and coffee mugs.

“Unlike the picture of the old man at Princeton with his chaotic mane of hair and his careless Chaplinesque attire, Einstein in midlife was an attractive, impressive man, whose features, eyes, speech, and mere presence aroused and indeed compelled attention,” writes the biographer Albrecht Fölsing.

“He was a rock star whose fame exceeded that of Hawking,” says University of Chicago physicist Michael Turner.

“It helps that Einstein is photogenic and gives good quotations,” Princeton historian Gordin says. “He is a media creation. There are photos of him with Charlie Chaplin, and it’s not a bad analogy — he’s a figure that fits that moment.”

The moment in 1921 was thoroughly modern. Einstein’s physics, as Walter Isaacson noted in his biography, resonated with the modernist movement in art, music and literature: “[M]odernism was born by the breaking of the old strictures and verities. A spontaneous combustion occurred that included the works of Einstein, Picasso, Matisse, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Joyce, Eliot, Proust, Diaghilev, Freud, Wittgenstein, and dozens of other pathbreakers who seemed to break the bonds of classical thinking.”

And so people didn’t really mind that someone had come up with a theory they couldn’t understand.

“I think what’s going on there is Einstein becomes more impressive as a sage insofar as he can’t be understood,” says New York University historian Matthew Stanley. “He’s talking about things so cosmic they’re beyond understanding. The fact that he understands them makes him more extraordinary. Einstein grasps this early on and plays to that.”

Cosmologist Katie Mack *09 of North Carolina State says that people like the idea that “there are these godlike supergeniuses that walk among us. ... There’s something about the archetype of the kind of crazy genius, somebody who has that kind of otherworldliness about them. Somebody who is not paying attention to fashion, he has weird hair, he has weird hobbies, he comes up with something nobody can understand.”

The newspaper reporters struggled, with limited success, to translate Professor Adams’ translation of Einstein’s lectures into something readers could digest.

“By specific illustrations with equations he proved that his theory of the end to infinity was correct, as far as can be shown by algebra,” the New York Tribune reported. “The main basis of his belief is that density of matter is not equal to zero and, therefore, that all space is finite, thus disagreeing with Newton, who tried to prove that density of space equals zero and that space is, on that account, infinite.”

The New York Times got closer to the gist of things: “We can no longer think of space, time and matter as independent concepts, but they are interwoven with each other.”

The final lecture incited this headline in the Times: “EINSTEIN CANNOT MEASURE UNIVERSE.” A smaller headline took a stab at an explanation: “Universe Called Finite and Yet Infinite Because of its Curved Nature.”

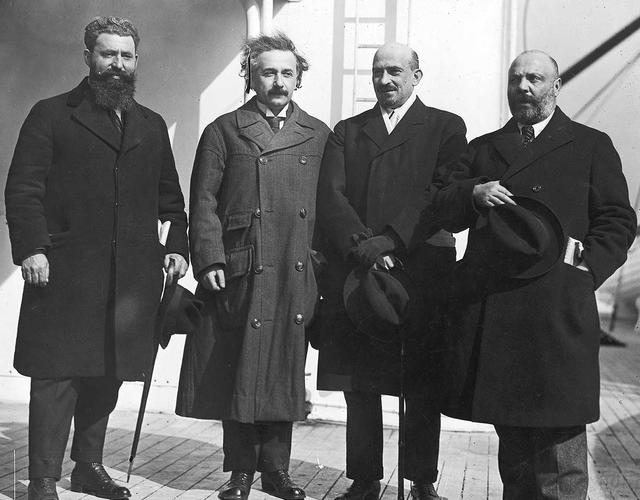

Einstein did not come to America to speak about relativity. Accompanied by his wife, Elsa, he came to raise money for the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He was invited by, and traveled with, chemist Chaim Weizmann, then head of the Zionist movement in the United Kingdom and later the first president of Israel.

Einstein was passionate in his support of the creation of the Hebrew University and would be present two years later at its inauguration. Amid the anti-Semitism in Germany (some critics of relativity derided it as “Jewish physics”), Einstein, though not religious, was identifying more closely with his Jewish brethren. He viewed his role on the trip as functional but somewhat undignified. He was a showpiece, paraded around in an effort to raise money from wealthy American Jews. He was quite blunt about it:

“I had to let myself be paraded like a prize bull, and make a thousand speeches at big and small meetings,” he wrote to his friend Michele Besso.

Einstein’s Princeton visit gave him a taste of life in a tranquil academic village. He would return a dozen years later. Amid the rise of the Nazis and intensifying militarism and anti-Semitism in Germany, Einstein renounced his German citizenship, and in 1933 was lured by Abraham Flexner to join the newly formed Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. The institute had no building at first, so Einstein and a handful of other institute professors camped out at the University’s mathematics department in Fine Hall.

“Princeton is a wonderful piece of earth and at the same time an exceedingly amusing ceremonial backwater of tiny spindle-shanked semigods,” he wrote soon after arriving in Princeton, according to Fölsing’s biography.

The Einsteins bought a house at 112 Mercer St., a short walk from campus. Elsa Einstein became ill and died not long after. Her husband became something of a loner, seen in the community as an endearing eccentric, and known for his long rambles about town. Peripatetic for so much of his life, he stayed rooted in Princeton until his death in 1955.

What few people in the audience in McCosh 50 on May 9, 1921, could have known was that the bulk of Einstein’s most important scientific work was already behind him. Einstein remained ambitious in the years that followed, and his status as the preeminent scientific celebrity only solidified. But a new generation of brilliant thinkers pushed physics into stunning realms where Einstein was never fully comfortable.

Einstein’s 1905 paper on the photoelectric effect (the only paper cited by the Royal Academy in awarding Einstein the Nobel Prize in 1922) was a foundational text of quantum physics, but Einstein was never happy with the probabilistic, indeterminate, causality-defying nature of the new physics, and famously declared that God does not throw dice. He spent much of his last three decades trying in vain to develop a “theory of everything” that would link all the fundamental forces in nature.

The mythology of Einstein the genius can obscure the collaborative nature of scientific breakthroughs. In his 1905 miracle year, was he really a lone genius operating in the lowly job of patent clerk in Bern? Katie Mack says that’s wrong: Patent clerk was an important job, and Einstein was in contact with other physicists, building on their work.

Is it true that he overthrew Newton? Einstein himself denied that, as quoted by Fölsing: “There has been a false opinion widely spread among the general public that the theory of relativity is to be taken as differing radically from the previous developments in physics from the time of Galileo and Newton. The contrary is true.” At another point, according to Isaacson’s biography, Einstein derided cults of personality: “It strikes me as unfair, and even in bad taste, to select a few for boundless admiration, attributing superhuman powers of mind and character to them. This has been my fate, and the contrast between the popular estimate of my achievements and the reality is simply grotesque.”

Einstein didn’t come up with “relativity” out of the blue. The term predated his theory. He didn’t think up the notion that objects contract as they accelerate: Hendrik Lorentz did. The field equations of general relativity were independently developed at the same time by David Hilbert. Even the “Eureka!” moment of the relativity story, the Eddington expedition’s confirmation of general relativity during the 1919 eclipse, has been questioned by scholars, who argue Eddington hyped ambiguous results.

Einstein cuts an appealing figure as a humanist and pacificist, but biographers describe him as rakish, sexist, and cold to many of his closest relations, including his wives and children. Fame did not protect him from criticism, and as he weighed in on social and political issues, he often incited controversy and tension among his friends and fellow scientists. In 1921 he was still getting his footing as a celebrity scientist, and after he returned to Europe, he wrote an article criticizing Americans for being money-obsessed, among other failings. That did not go well back in the United States. He also gave an instantly notorious interview with a newspaper reporter in which he described American men as “toy dogs” of their women, whom he derided as superficial spendthrifts. That drew a rebuke in The New York Times, which suggested that Einstein stick to physics.

Such incidents are now footnotes in the Einstein biography. The controversies have largely receded from popular knowledge. Einstein became something more like the common property of humankind, an archetype of genius.

But there is another Einstein characteristic that perhaps is too easily ignored: his fearlessness. It takes courage to push into uncharted realms and report unflinchingly on one’s discoveries, not all of which may be welcome. It’s not as if people were hankering to kick Newton to the curb. Even something as seemingly simple as a lecture tour in America took a great deal of verve and confidence — a willingness to plunge into new and potentially dangerous waters. Reading the accounts of Einstein trying to describe relativity to Americans, the reader feels compelled to give the man credit simply for showing up.

There’s an odd passage at the close of one of the articles on Einstein’s Princeton lectures, which ran on May 12 in the Monmouth Democrat of Freehold, N.J.: “A fascinating inference of the theory of relativity is that ‘the apple,’ which Sir Isaac Newton observed falling in 1667, ‘is still falling.’”

The story does not explain this observation or what Einstein said to prompt it. But Einstein’s theories do contain bizarre implications, including the equivalency of the past and future and the disappearance of a preferential point in time that we call “now.”

And so, in a sense, Einstein is still there in McCosh 50, still waving his chalk like an orchestra conductor — still telling us the secrets of the universe.

Joel Achenbach ’82 is a staff writer for The Washington Post.

14 Responses

Roland M. Frye Jr. ’72

4 Years AgoAnother Einstein Story

Thanks to Leonard Milberg ’53 for his stories about Albert Einstein (Inbox, November issue). I’d offer another, also from that era at Princeton. When my father, Roland Frye ’43, was in graduate school at Princeton in the late 1940s and early 1950s, he would often clear his mind by taking long walks around Lake Carnegie. On one such walk, he noticed a sailor, way out in the lake, trying quite unsuccessfully to direct his sailboat. He could not control it at all. As my father continued his walk, he thought to himself, “This guy has no sense of vectors or any other mathematics associated with moving an object from one place to another.” A half-hour later, as my father returned home, he noticed the same man finally docking his sailboat. The sailor was Albert Einstein.

Hugh McPheeters ’64

4 Years AgoTeaching Relativity

The lead article in the May 2021 Princeton Alumni Weekly entitled “Einstein at Princeton” got me to thinking about relativity theory. While I majored in history, I did take three semesters of physics including one billed as advanced physics for non-science majors. As I recall, this course spent two weeks on special relativity and the rest of the semester retracing the historical development of quantum mechanics. I have had an interest in these subjects ever since.

Here is an idea that came, or came back, to me as a result of the article. I doubt very much that it is original and suspect that it was part of Einstein’s thinking when he developed his general theory of relativity.

Visualize a tall, thin rocket. (Not necessarily a rocket ship since it need not carry anything except the propellant or fuel that powers it.) Now let’s say that as the rocket approaches the speed of light — the universal speed limit — it has a lot of fuel left, say more than half. As it burns this additional fuel very little of the propulsive energy can go into increased velocity.

The only thing that makes sense is that in order to maintain the universal speed limit the mass of the object being propelled or pushed must increase. As a result of this increase, each additional unit of fuel burned and energy expended goes less into increasing velocity and more into increasing mass.

As indicated, I suspect this was one of Einstein’s insights as he developed his theory, a cornerstone of which is the equivalence of mass and energy. It seems to me that the illustration is simple enough that it could be taught to students at pre-college levels.

Bob Davies ’58

4 Years AgoA Friendly Neighbor

I was the first-born in my family in 1936. By 1938 the family had moved to Princeton and my Dad began his studies for a Th.D. (doctorate in theology) at the Princeton Theological Seminary. The family rented an upstairs apartment in a house on Nassau Street not far from the home of Albert Einstein. My mother used to put me in a playpen near the sidewalk and goes upstairs where she could keep an eye (and ear) on me. Einstein would walk by on occasion. Before doing anything he would check that there were no observers. If nobody was around, he would approach me, pat me on my head, and say something in German.

When walking home from grade school with my classmates we would often see Einstein walking, but we never disturbed him.

Einstein came to my father’s graduation. He was driven there by my mother. I rode in the back seat. Einstein said in his Germanic tone, “My, what a beautiful car.”

The story has an unhappy ending. In the spring of 1955 I was a freshman engineering student at Princeton University. Although I had passed the fall semester’s work, I failed all but one of my spring semester classes. Einstein died in Princeton in the spring of 1955. Our Princeton careers ended at the same time.

Leonard L. Milberg ’53

4 Years AgoA Pair of Einstein Stories

One day in my sophomore year I suddenly learned that Albert Einstein (“Einstein at Princeton,” May issue) was soon to make an appearance at the Jewish Center, which then was a modest room in Murray Dodge. I rushed there to find the few remaining seats were placed in a semicircle behind the podium. Almost immediately after I sat down the great man appeared sitting next to me. His footwear: sandals without socks.

Soon the eminent professor was at the podium speaking on behalf of the United Jewish Appeal. Einstein eloquently described the horrible plight of Europe’s remaining Jewish community and its dire need for financial support.

A question-and-answer period followed, during which Einstein was questioned about the then-front-page news that his former colleague, Klaus Fuchs, was just arrested for being a Russian spy. Einstein looked bewildered, having no idea who Fuchs was. Suddenly, as if struck by lightning, he bellowed the name using the German pronunciation, which sounded like the obscenity. Loud laughter erupted. I clearly observed that Einstein had no idea what was so funny.

I also recall Bill Scheide ’36, Maecenas who, among his numerous gifts to Princeton were a Gutenberg Bible and several manuscript Bach scores, recounting how he heard what Bill believed was Einstein’s first lecture in English. Unannounced, he stood before Bill’s 9 a.m. class and proceeded to describe the Theory of Relativity. Einstein was a friend of the professor who taught the course and over the weekend, once he learned the subject of Monday’s lecture, offered his services.

Linda Longmire w’57

4 Years AgoA Memorable Bow

After seeing your fascinating issue on Einstein at Princeton I was reminded of a wonderful story that my beloved late husband, Tim Smith ’57, shared with me and others about his time as an undergraduate at Princeton. He and his friend Hugh Cannon ’57 were studying in the library late one night and were taking a study break out in the entrance vestibule. They suddenly looked up and saw an old professor with a load of books coming down the narrow hall. They noticed the sandals and then the hair, and with shock and awe, they confirmed that it actually was the great Einstein. For Tim, Einstein was not only the genius of contemporary physics, but also the consummate moral genius. They were stunned and had no idea what to say in this close encounter with such greatness in the tiny passageway. But when Einstein approached, the friends, without even a word to confer, spontaneously and reverently bowed since of course no words would have been sufficient. Einstein stopped right in front of them and stared deeply into their eyes. Tim said he could recall the details of his gaze throughout his whole life. And then, with the great humility and humanity that Einstein always embodied, he bowed back to them.

Many decades later when Tim retired from full time teaching as a Professor of the Foundations of Education at Hofstra University, a big retirement party was held for him where this story was recounted. One of speakers said that of course everyone could recognize and appreciate the genius in the great Einstein; but Tim, as an empathic and inspiring teacher, was the rare person who was able to discover and encourage the hidden genius in so many undergraduate and graduate students. At the end of the event the gathered crowd was obviously moved and spontaneously rose and bowed to Tim. Years later in 2018 at the memorial held for Tim’s passing, one of his many former students, a professor himself, gave a moving tribute to Tim referencing that unforgettable experience with Einstein entitled “Tonight We Bow Back.” And once again they did.

Dana S. Scott *58

4 Years AgoIn a Strange Country

When my wife and I moved to Princeton in 1970 we met Einstein’s devoted former secretary, Helen Dukas. She recounted a story of the Einsteins moving to Princeton. They were told that there is this strange American holiday called “Halloween” when children come around demanding “Trick or Treat.” Einstein was enchanted and bought apples and candies to give out. He stood waiting by the door on the special night — but no one came. Apparently parents had said: “Oh, that is Prof. Einstein’s house. You mustn’t disturb him!” I do hope the story is true.

William E. Gilbert ’50

4 Years AgoEinstein in his Rocking Chair

The highlight of a son’s Princeton graduation is the event itself, with all the speeches and formalities. Not so with the Gilbert family. With the shortage of hotel rooms in Princeton town on that most important weekend, son Bill had to put his parents in “date lodging” at 18 Mercer St.

Arriving with plenty of time on the big day to get seats on the Nassau Hall lawn, we began our walk slowly up Mercer Street, enjoying the perfect weather and flowers on both sides of the street. Suddenly, my mother stopped and whispered in my ear, “Billy, Billy! There’s Albert Einstein!” And indeed there he was, in his rocking chair on his front porch. He was reading and smoking his pipe, so he did not notice the astounded Gilbert family.

My dear mother attended several other graduations with me, and she would always bring up the Einstein encounter, regardless of who was graduating. That was the only time in my four years at Princeton that I saw the great man. My roommate, a physics major, was jealous of my good luck.

Tom Benghauser ’66

4 Years AgoEinstein, Football Fan?

This is an excerpt from Spook McClintock, Fritz Crisler, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and The Kiski Kids, the comprehensive account I have written of the Princeton football teams that in 1933, ’34, and ’35 scored 25 wins, lost just one game, and won two national championships. Its availability in e-book and paperback formats is imminent.

“[I]n the Thirties the Princeton campus — students, faculty, administrators, and other employees — was not only more close-knit than, for better or worse, it is today but also much more interested in and supportive of Tiger football.

“In October 1933, for example, Albert Einstein arrived in the U.S. to take up a position that he held until his death in 1955 at the Institute for Advanced Study, which was established in Princeton with financial support from Newark retailer Louis Bamberger and his sister Caroline Bamberger Fuld as a center for theoretical research and as a haven for Jewish scientists fleeing the Nazis. For six years from its opening that year, it was housed in Fine Hall, home to Princeton’s mathematics department.

“According to Kiski Kids Kid Bob Kopf ’66, “Walking alone across the Princeton campus in the 1930s, my father encountered Albert Einstein. To Dad’s astonishment, Einstein stopped him, indicated that he knew my father was on the football team, and asked about the prospects for the autumn clashes. Dad had a brief, yet highly pleasant, interaction with the brightest man on the planet.”

Leo Damrosch *68

4 Years AgoEinstein and Newton (and Wordsworth)

Since Joel Achenbach ’82 writes about Isaac Newton in his excellent piece about “Einstein at Princeton” (May issue), it may be of interest to identify the source of his quotation from the dean who “described Einstein as a Columbus ‘voyaging through strange seas of thought alone.’” The line actually refers to Newton himself. There is a magnificent statue of him by Louis-François Roubiliac in his Cambridge college, Trinity. William Wordsworth, who had been a student in neighboring St. John’s, speaks of it in his poem The Prelude:

… I could behold

The antechapel where the statue stood

Of Newton with his prism and silent face,

The marble index of a mind for ever

Voyaging through strange seas of Thought, alone.

Edward Perry ’56

4 Years AgoThe Time I Saw Einstein

In early January 1953 as I was leaving the then Green Engineering Building around about 6:00 a.m., I saw the unmistakable Einstein hair walking down the sidewalk away from me. A wonderful experience for a freshman civil engineer!

John Steel ’56

4 Years AgoBreathtaking

I too was moved at a sighting of Albert Einstein trudging through town. It was rare and memorable. We, early in our indoctrination, had been told not to approach Professor Einstein: He may be thinking.

Michael Otten ’63

4 Years AgoMe Too — Age 11, 1953, at My Father’s 25th Reunion!

My first memorable brush with Princeton was my father’s 25th reunion in 1953. There were two noteworthy events inscribed in my mind as impressions of an 11-year-old: being introduced to Albert Einstein by my father, when we happened to pass him, going in opposite directions in front of Fine Hall, and sliding between the legs of Brad Glass (one of many football legends of those days) during a reunion softball game for celebrants’ children.

David Derbes ’74

4 Years AgoMore About Einstein’s Life and Work

For such a life as Einstein’s it is impossible to get all the details in full, and likely some of what I write here will also be in error. It is true that relativity as a term predates the 1905 paper, and that many were hot on the trail of the special theory when Einstein formulated it. The principle goes back to Galileo, who in his epochal book on the two great systems of the world (Ptolemaic and Copernican, published 1632) describes the inability of distinguishing uniform motion from rest by a passenger below decks in a smoothly sailing ship. The contraction hypothesis of Lorentz (and also G. FitzGerald) was entirely ad hoc, designed to explain the null result of the Michelson-Morley experiments. In Einstein’s special relativity, the contraction follows ineluctably from the 1905 postulates. For the most part the others looking at special relativity were primarily mathematicians (Lorentz is the great exception), whereas Einstein’s vision was firmly rooted in natural phenomena. To say that the gravitational field equations a decade later were developed by Hilbert simultaneously with Einstein is baldly true; but Einstein had tutored Hilbert in all he had learned and hypothesized over the previous four years or so, at which point Hilbert had the theory all but served up to him on a platter. For Hilbert, then the greatest mathematician alive, the derivation of the field equations (from a Lagrangian) was pretty much an exercise. (Even Hilbert needed help a year or two later with Einstein’s theory, and got it, from the woman Einstein described as “the most significant creative mathematical genius thus far produced since the higher education of women began”, the algebraist Emmy Noether.)

I’m a retired high school physics teacher, and my knowledge of history is modest. Most of the scholars I’ve read believe that while we might have gotten special relativity within a few years if Einstein had not been born, the general theory was the work of one man, though with a mathematical assist. Early on, Einstein’s old friend Marcel Grossmann, who unlike Einstein, had attended their college lectures on differential geometry, helped him with his math. I also think that Dr. Mack is overestimating Einstein’s connection with other physicists. The technical people in the patent office were typically engineers, not theoretical physicists. It’s been suggested that before his first academic appointment in 1908, the only physicist he saw on a regular basis was in his own mirror.

Finally with respect to Einstein’s sexism (an unfortunately near-universal attitude among men of his generation), it should be pointed out that he wrote a stern letter to The New York Times (published May 4, 1935, quoted above) upbraiding them for not affording Noether sufficient notice following her recent death. Like many Jewish scholars, Noether was forced to leave her position at a German university (Göttingen) and come to America. Sadly, she was not offered a position at Princeton, owing to her sex, though she was a frequent visitor. Fortunately, Bryn Mawr was not so far away, and they were very glad to have her.

Norman Ravitch *62

4 Years AgoPrinceton’s Honor, Though Undeserved

Princeton’s reception of Einstein, both the first and especially the second time around, was an honor for Princeton, but let’s remember that at both these times few Jews were permitted matriculation at Princeton and even fewer professors from that group were appointed. In Germany at the same time, however, no sooner had Einstein risen to speak than fascist hecklers sounded their views; at the same time Jews were more welcome at German higher learning institutions than at Princeton, Harvard, or Yale. The truth often hurts.