Eisgruber Takes Charge

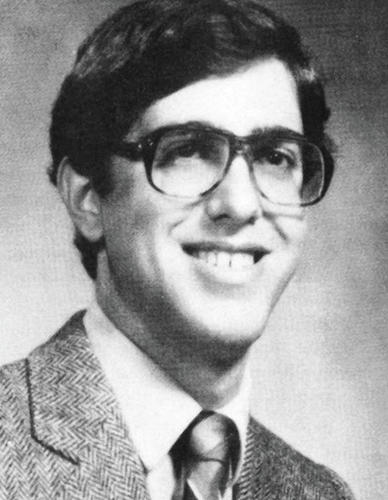

The new occupant of One Nassau Hall is a folk-rock fan with a sharp sense of humor and a deep interest in ethics — and a plan to spend the year listening

Christopher L. Eisgruber ’83’s move from the provost’s office to the president’s suite took him only a few dozen yards along the first-floor corridor of Nassau Hall. His predecessor, Shirley Tilghman, graciously moved out a week early; by the time Eisgruber moved in July 1, his office was ready for him. The walls had been repainted, Tilghman-era blue giving way to Eisgruber-era beige; the boxes unpacked. A day later, what pleases the new president most is that his books are on the shelves. “I feel at home with my books around me,” he says.

The Princeton community seems to feel at home with Eisgruber, who as provost earned a reputation for listening, reaching out, and building consensus. His selection has been widely seen as a vote for continuity; the transition appears to have been, as Tilghman promised, “seamless.” After all, Eisgruber had been the University’s second-ranking officer for nine years, with a finger in almost every Princeton pie.

Even so, anyone looking for insights into the new president’s thoughts and values might want to start someplace other than his freshly painted, book-filled office. Instead, walk down the corridor past the provost’s office (now occupied by David S. Lee *96 *99) and out of Nassau Hall to Mathey College, where a few years ago Eisgruber taught a freshman seminar called “In the Service of All Nations? Elite Universities, Public Policy, and the Common Good,” which examined Princeton’s role in society.

Eisgruber taught the course partly to drive himself to delve deeper into the literature on higher education. He also wanted his students to ascertain the core values of an elite university and apply them in practice — and so students read everything from University policy papers to books on higher education to Supreme Court decisions on affirmative action. “You could tell that he really wanted us to look at what the University owed to the community through several lenses,” says Caroline Hanamirian ’13, co-winner of this year’s Pyne Honor Prize. Jake Nebel ’13, who shared the Pyne Prize with Hanamirian, also was in the seminar; he describes it as a “class in applied ethics.”

The freshmen quickly learned that their professor expected them to be actively engaged in their own education — it was not enough to absorb information. And so it’s no surprise that in one of his first acts as president, Eisgruber asked each freshman to read the book The Honor Code: How Moral Revolutions Happen, by Princeton philosophy professor Kwame Anthony Appiah. To make this exercise more than just an advanced high school summer-reading assignment, he posed specific questions for the students: What does honor mean within our society? What honor practices do you and your peers participate in? To what extent are those practices healthy ones? This fall, the freshmen discussed these questions in their residential colleges (alumni may participate online via student-led “E-Precepts”). Eisgruber hoped the Princeton Pre-read, as it is called, would enable many people in the University community to read and learn together.

Since Eisgruber was named Princeton’s incoming president in April, writers covering the appointment have struggled to find things that might surprise Princetonians who knew him as provost. There are a few. Alongside his intensity is a sharp wit and self-deprecating humor. He unwinds with thrillers and mystery novels, and subscribes to Rolling Stone. As an undergraduate, he worked for independent presidential candidate John Anderson, then interned for a Republican governor, and contributed to Barack Obama’s campaign during the last election. He loves folk-rock music, particularly singers Sara Borges and Jake Bugg. “Jake Bugg is to Bob Dylan what Amy Winehouse was to Motown,” he explains, making a comparison that is only comprehensible to, well, someone who subscribes to Rolling Stone.

Eisgruber; his wife, Lori Martin; and their 10th-grade son, Danny, will move into the president’s residence, Lowrie House, in the winter; Martin will continue commuting to her job as a securities litigator in New York. “We’ll be present [at University functions] as a family,” Eisgruber says, “but we’re going to be present as a family in a way that is a 21st-century family, and a family like many others around the University.”

The child of German immigrants who met as graduate students at Purdue University, Eisgruber was born in Lafayette, Ind., and moved to Corvallis, Ore., when he was 12 and his father became dean of the School of Agricultural Sciences at Oregon State University. In high school, Eisgruber edited the newspaper and led a national championship chess team. If it sounds like a high-achieving but unremarkable family, Eisgruber later would find that there was more to the story. Only as an adult, when he was helping his son with a school project on family history, did he learn that his mother had been guarding a great secret: Eva Kalisch Eisgruber, who long had professed to be Catholic, had been born Jewish and fled the Nazis as a young girl. She cut ties to her family when she married Eisgruber’s father, Ludwig. Both parents had died before he made his discovery, and so he never discussed it with them.

“I was disequilibrated. Bewildered at first,” Eisgruber told the Israeli newspaper Haaretz. “You think things are true about your childhood, and suddenly you find that things were very different.” Eisgruber continued: “Understanding myself as Jewish helps me understand who I am ... . ”

For college, Eisgruber chose Princeton because he wanted to learn more about the theory of relativity. Friends remember him as a studious undergraduate typically found on a lower floor of Firestone Library; to this day, he cites its open stacks as one of his favorite places on campus. As a senior, he wrote a column for The Daily Princetonian in which he stressed the importance of studying the great books, saying it was too easy to “come into the curriculum asking narrow questions, and unless we choose with care, find a series of courses all asking the same narrow questions.” He suggested that every Princeton student should be required to take at least two upper-level courses involved in intensive study of these books.

By then, Eisgruber’s interests had swung from physics to law. He credits Professor Walter Murphy, whose course in constitutional interpretation was legendary to a generation of Princeton undergraduates. Murphy gave a 90-minute lecture each week; deeper work was done in weekly two-hour seminars, where the students examined the theoretical underpinnings of the Constitution and teased out its practical applications. Eisgruber remembers delving so deeply into some Supreme Court decisions that he could recite them almost word for word. Preceptors sometimes broke the seminars into moot-court sessions, pairing students to argue the merits of a made-up constitutional case and assigning the rest of the class to sit as judges and write opinions. To Eisgruber, it was heaven: “I remember thinking, I could do this for the rest of my life!”

As a junior, he took Professor Jeffrey Tulis’ course on the presidency, which looked at important presidential decisions and examined the philosophical underpinnings of the office. Tulis, now at the University of Texas, later would write a letter of recommendation when Eisgruber applied for a Rhodes scholarship and help him prepare for his interview. (Eisgruber got the Rhodes, and earned a master’s degree in politics at Oxford.)

Eisgruber joined Elm, a nonselective club, but “was definitely not the toast of Prospect Avenue,” recalls Hyam Kramer ’83. Because he was a teetotaler at the time (he now drinks wine socially), “certain aspects of Prospect Street [were] unfriendly to me,” Eisgruber acknowledges. “I can empathize with those students on our campus who may say, ‘You know, that’s not something that appeals to me right now.’ ”

When Kramer and two other close friends went independent, Eisgruber moved with them into Spelman Halls for his senior year. Their social life centered around long debates — they didn’t even have a TV set. “Whenever he would open his mouth, it was always interesting,” says Kramer. “He had a powerful belief in right and wrong, and a willingness to admit when he hadn’t made up his mind. He was passionate to get to the bottom of an issue.”

At Tulis’ urging, Eisgruber applied to law school. He attended the University of Chicago, where he met Martin and became editor-in-chief of the law review. After clerking for Judge Patrick Higginbotham on the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, Eisgruber went to Washington to clerk for Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens. Stevens’ three clerks worked in offices on different floors of the Supreme Court building: two in a larger downstairs office near Stevens’, and one alone upstairs. For obvious reasons, clerks usually considered the downstairs office more desirable, says Lewis Liman, one of Eisgruber’s fellow clerks, but Eisgruber chose the upstairs office because it was quieter.

Justice Stevens remembers Eisgruber as “an intelligent and wonderful person.” One case that year, Texas v. Johnson, raised the question of whether burning the American flag was protected under the First Amendment. Stevens dissented from the Court’s 5–4 decision that flag-burning is protected speech, and assigned Eisgruber to work with him on the opinion. “I’m not sure he agreed with my views,” the justice recalls, “but that didn’t affect the quality of the help he gave me at all.”

Eisgruber’s parents urged him to choose law over academia, citing low faculty salaries and uncertain employment prospects. “I tricked them by going to law school and becoming an academic later,” he jokes. He joined the faculty at New York University’s law school in 1990 and returned to Princeton in September 2001 as a visiting fellow in the Program in Law and Public Affairs, accepting a permanent appointment a year later.

Tilghman’s decision to name Eisgruber provost in 2004 caught him by surprise, but over the next nine years he worked closely with her on almost every area of University policy. He also found time to write, publishing three of his four books — on religious freedom, human rights, and the Supreme Court confirmation process — during that time. His greatest challenge came during the 2008–09 recession when, in the space of a few months, the endowment lost more than 20 percent of its value. He and other University leaders assembled a crisis budget that included deep spending cuts and, for the first time in memory, staff layoffs.

The budget struck at the cherished notion of the University as a community, and it was far from clear that the group had struck the correct balance. “If you cut too deeply, you reduce the excellence of the University,” Eisgruber says, explaining the dilemma. “But you also put the University at risk if you don’t cut enough” and the downturn worsens. Some of the people whose jobs he was eliminating or whose salaries he was freezing were friends.

Tilghman praises Eisgruber’s ability to explain the tough choices, calmly and methodically, to the rest of the University community. “I think it’s that instinct to be inclusive, to treat everybody like an adult who needed to understand how serious the circumstances were, and then to elicit the support of everyone on campus to help us get through it.”

In the short term, any shift in policy as Eisgruber begins his term is expected to be almost as subtle as the change in the color of his office walls. Two potentially controversial reports, initiated by Tilghman, were on the horizon: one addressing the need to increase diversity among the faculty, senior administrative ranks, and graduate-student body (see page 14), and the other recommending ways to improve access for low-income students. He supports the long-discussed creation of a program in Asian-American studies, and has been working with faculty members to design a curriculum. He has been actively involved in discussions over how Princeton should be involved in online education, and backs the expansion of global initiatives, such as a planned Princeton office on the campus of Beijing’s Tsinghua University to support Princeton faculty and students in China. “One of the most important things to the future of the United States, the future of China, and more generally the future of the globe is to create channels of communication between the people who are going to be the leaders in the future,” he says. “You want people to have the capacity to conduct those conversations.”

He also strongly supports two controversial Tilghman policies, grade deflation and the ban on freshman rush, but when reminded of Tilghman’s aspiration that every undergraduate belong to both an eating club and a residential college, Eisgruber sounds very much like the independent he once was. “I think every student at Princeton needs to feel fully included within our community and needs to feel able to participate in the options that are attractive to them,” he says. “I think we need to remember that some of our students who flourish here may not feel that that is about either a residential college or an eating club.”

Asked about his vision of the job he has assumed, Eisgruber seems nonplussed for a moment, then launches into a detailed answer that makes clear he has given the question a great deal of thought. “I think what university presidents do is interpret the aspirations of their community and then help to mobilize the community behind those aspirations,” he says. “Part of what you have to do is listen, part of what you have to do is play back, and part of what you have to do is inspire and organize people.

“I really am at a stage at this point where I want to take some time to listen to people,” he says. “We’re moving strongly ahead with a set of initiatives that had commenced under Shirley’s leadership and that I feel very enthusiastic about. And that combination, together with listening to what people have to say about the future, I think is the right way to approach the first year.”

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

No responses yet