What is ailing Princeton football?

The program’s last winning season came in 2006, when Princeton shared the Ivy League championship with Yale. In the five seasons since, the Tigers have gone 10–25 in Ivy League play and won just one of 10 games against Harvard and Yale. Through Oct. 8, they were 1–0 in the league.

That record of futility gnaws at alumni, and it prompted former tackle Eric Dreiband ’86 to write a letter to President Tilghman — which was signed by 200 other alums — arguing that the football team’s chances of winning have been hurt by policies unique to Princeton.

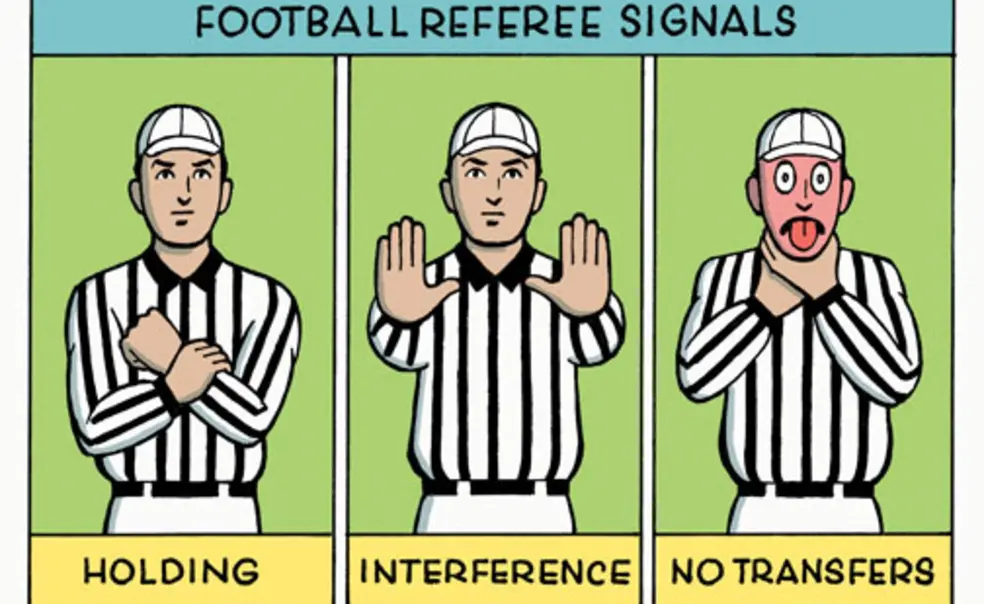

The policy cited in the letter that damages Princeton football the most is probably the University’s decision not to accept transfer students. Every other Ivy League school accepts transfers, and some of those students have made a big difference on the playing field.

We’d like to hear your reaction to the views expressed in this essay. Write to PAW, email paw@princeton.edu, or post in the comments section below.

Responses will be published in a future issue and at PAW Online.

Three Yale teams received a major boost last year from transfer students. Patrick Witt, who arrived at Yale after playing for a year at big-time Nebraska, was the star quarterback for three seasons, though the team managed only an 11–10 record for the Elis. Transfer students also helped Yale’s men’s swimming and women’s tennis teams achieve winning seasons.

Harvard’s football team has a 57–13 Ivy record — and four championships — in the last decade, thanks at least in part to a string of transfers such as running back Clifton Dawson, who came from Northwestern and still holds the league record for career rushing yards.

There was a time when Princeton did admit transfers, but they weren’t necessarily magic bullets. Among the most celebrated was quarterback Jason Garrett ’89, now the coach of the Dallas Cowboys, who transferred from Columbia. Garrett was the Ivy League Player of the Year in 1988 and set a still-standing league record for career completion percentage, but Princeton went just 8–6 in league games during his two years at quarterback.

A few years later, Princeton adopted its no-transfer policy. This was done to save as many openings as possible for the talented applicants the University was seeing each year and, according to provost Christopher Eisgruber ’83, to make sure that all students had a “cohesive, four-year experience.”

“There are reasonable arguments on both sides of the transfer question,” allows Eisgruber, adding that the University has no plans to reconsider it anytime soon. “Arguments based on the athletic program, however, strike me as singularly unimpressive. We already win more Ivy League titles than any other university.”

All true, but it’s hard to imagine why Princeton wants to be the only school in the league playing by tougher rules. It’s not just Princeton football that would benefit from accepting the occasional, well-chosen transfer. He or she could just as easily be a super-talented sophomore biologist, actor, or musician. Sure, he or she would miss things like Cane Spree and freshman seminars, but the extraordinary candidates Princeton would pick could find a way to fit in while adding to the University’s luster.

Merrell Noden ’78 is a former staff writer at Sports Illustrated and a frequent PAW contributor.

4 Responses

Stockton Gaines *69

10 Years AgoDebating the transfer ban

Both my father (’23) and grandfather (1886) spent a year at West Virginia University before coming to Princeton. My father, at 6 foot 5 inches, was center on the basketball team and played other sports. I do not know if his, or my grandfather’s, sports abilities were a factor in their being accepted at Princeton, but I do know that both they and Princeton benefited. The argument about needing to be at Princeton for all four years to get a “cohesive” experience seems like nonsense, and perhaps a bit arrogant. Reconsider.

Stewart A. Levin ’75

10 Years AgoDebating the transfer ban

Whatever the other arguments for or against admitting transfer students (Extra Point, Oct. 24), football “parity” ranks at the bottom of my list. Indeed, our former president Bill Bowen *58, co-author of The Game of Life: College Sports and Educational Values, might well respond to that argument with mighty oaths were he not a true gentleman. That study’s empirical evidence, which included Princeton, identified: (a) that the true bottom line of athletics programs is red ink, (b) there’s almost no chance any more of walk-on players participating in major-sport intercollegiate competition, (c) the majority of alumni do not consider boosting support of athletics a priority, but trustee positions are over-weighted in favor of former athletes, (d) athletes on the whole have significantly lower academic performance than the general student population, (e) athletic-weighted admissions improve diversity measures by a paltry 1 percent, (f) admission committees are hesitant to admit an athlete with a stronger academic record, rather than a person the coach has specifically recruited for his team ... and the list goes on. By all means, let Princeton revisit its transfer policy, but sports parity should be given the low, or even negative, weight it deserves in the universe of values and priorities that a great university must uphold.

J.E. Murdock III ’69

10 Years AgoDebating the transfer ban

I think that it is absurd to not permit Princeton to do what it did before and to do what the other Ivy schools are doing. Please allow transfers quickly. If the student meets Princeton’s standards, then (s)he should be accepted if the transferee is a talented artist, a gifted musician, a Latin scholar, or an athlete, or all of the above.

Eleanor A. Vivona-Vaughan ’79

10 Years AgoDebating the transfer ban

Wow, did I have a negative reaction to this article. To propose that any university should adopt (or reinstate) a transfer policy simply because it needs talented athletes (football or otherwise) is offensive.

I was a junior-year transfer student in 1977 and was not chosen for my athletic prowess. We were 24 students chosen from a pool of 800. I was older than the other undergraduates and had two small children — the “token” nontraditional student. Women weren’t yet welcome on campus — never mind older, married undergraduate women with children.

I lived off campus and missed most events because I was busy raising twin boys. I had to study at home for obvious reasons. I didn’t fit in; I was not a “magic bullet”; and yet, the other students (not the “old boys”) welcomed me with open arms. I graduated Phi Beta Kappa and went on to get a doctorate — so I believe I added, at least a little, to the University’s “luster.”

I would urge that if the University is going to reconsider the transfer policy, it do so for reasons other than to find athletic talent. Perhaps a search for athletes can be part of the process, but certainly not the “driver” for the policy. To reduce transfer students to fodder for an athletic mill is reprehensible.