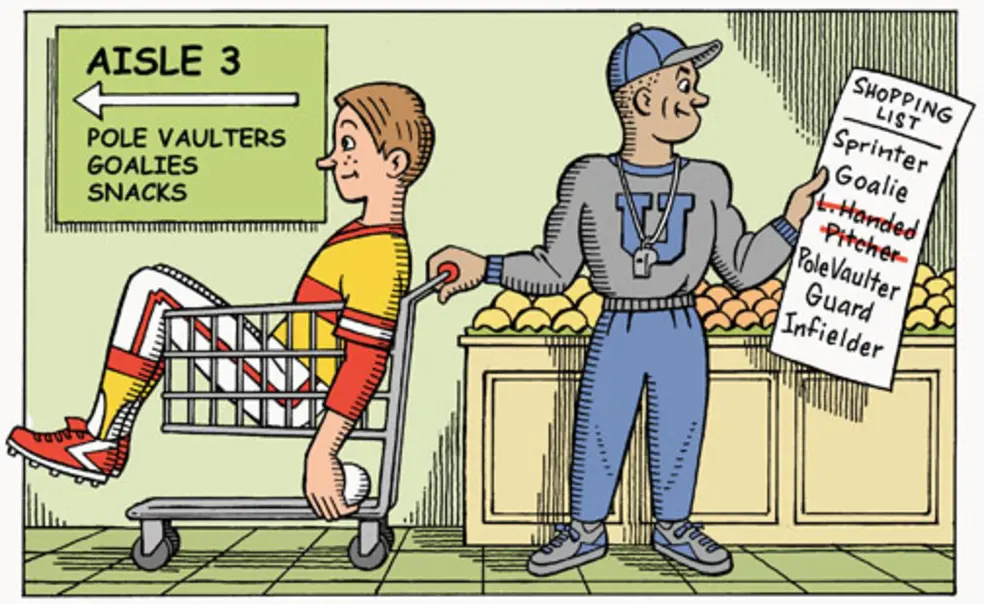

EXTRA POINT: Recruited athletes and other unmentionables

Of all the things college admission folk would rather not talk about, recruiting athletes probably tops the list. When I sent an interview request to Diana Caskey ’85, the women’s swimming coach at Columbia, the reply from a spokeswoman said, “We do not discuss the intricacies of the recruiting process with media outlets.”

Ivy League coaches are reluctant to talk about recruiting — often ordered not to — as if counting athleticism in an applicant’s favor were a shameful secret. Playing quarterback is seen as fundamentally different from playing Hamlet or singing opera.

“There’s tremendous concern at all the Ivy League schools to make sure it’s understood in the outside world that these are academically prestigious institutions,” says Dan Roock ’81, who, after coaching at Princeton, is now a Dartmouth rowing coach.

So I was surprised to find that Princeton’s dean of admission, Janet Rapelye, was more than willing to discuss this topic. She is, it turns out, a sports fan. She knows that Dave Slovenski ’12 is not only a top pole vaulter, but also a strong student and a leader with the Colosseum Club, a sporty alternative to Prospect Ave. “Our coaches are very good at recruiting the right students,” she says. “I’ll do whatever I can for our coaches. But we reserve the right to say no.”

To guard against sacrificing academics on the altar of athletic ambition, Ivy League recruits must have a league-mandated minimum score on a scale called the Academic Index, which is calculated with GPA and standardized test scores. “It’s meant to be a moment for us all to stop and say that our teams should reflect the quality of our student body,” says Rapelye.

While it’s possible to admit an athlete who’s scored below the minimum A.I. standard (such as a foreign student who didn’t understand the SATs), she says it’s rare and frowned upon by the other schools. “I’m a big fan of the A.I. It’s very straightforward,” says Rapelye. Meeting that threshold doesn’t mean an athlete is admitted automatically, she adds.

Coaches tell the admission office their needs and provide write-ups on the applicants, describing their athletic achievements and intangibles like leadership qualities. Princeton coaches rank the athletes, though some other schools don’t.

“We do it individual by individual, sport by sport,” says Rapelye. Except for football, which is limited by league rule to 120 recruits in each four-year cycle, there are “no set numbers,” Rapelye says.

But other schools’ coaches are given specific numbers by admission officials. Roock says he is allotted a number, depending on the needs of his team and other teams at Dartmouth. He can’t divulge the figure.

The year ends with coaches and admission officers reviewing how recruited athletes fared as students and members of the community. “Our students are doing a great job,” Rapelye says. She points out that it’s difficult work to be a Division I athlete and a Princeton student. For a dedicated fan like me, watching a Princeton sporting event will be even sweeter knowing that our athletes really are students.

Extra Point explores the people and issues in Princeton sports.

Merrell Noden ’78 is a former staff writer at Sports Illustrated and a frequent PAW contributor.

1 Response

Pam Phillips Torrey ’83

10 Years AgoQuestioning ‘verbal commitments’

I have been meaning to comment on the article in the March 21 issue by Merrell Noden ’78 (sports), and was reminded to do so after reading an article in The Portland Press Herald. The article was about a lacrosse player on the Cape Elizabeth High School team. She is a junior and the article stated that she has “verbally committed to Princeton.” In light of the comments of Dean Janet Rapelye and the Academic Index, on what exactly is Princeton basing its “acceptance” of an athlete who is only in her junior year? Her sophomore-year grades and PSATs? I was surprised that Mr. Noden didn’t mention this practice of “verbal commitments” by athletes who haven’t even finished junior year of high school.