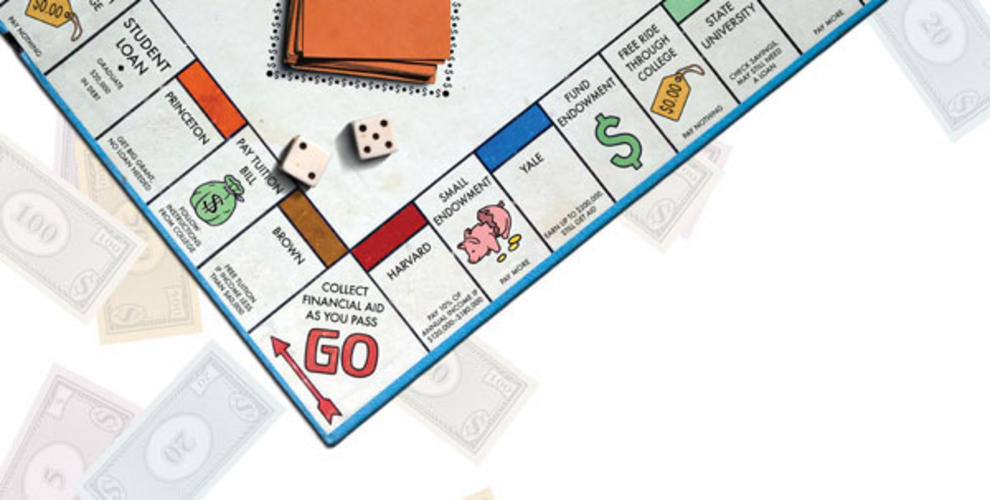

Financial aid: Who wins?

As elite schools offer financial aid to more affluent families, other colleges struggle to stay in the game

“Your money is always greener before your tuition’s paid, And if the years are leaner, you must get financial aid. And so the administration, not too many days ago, they changed the situation. Now all can afford to go ...

Princeton is free! Princeton is free! We’ve got to keep it the best-kept secret in Ivy League! The Orange and the Black the way to go, everyone else pays through the nose.

We’ve got the plan here, save all your clams here, Princeton is free!”

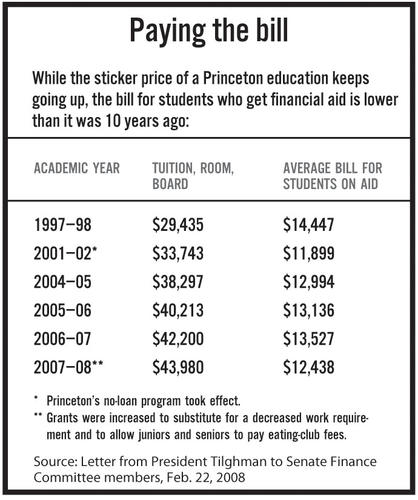

The Nassoons’ song, a crowd favorite the group set to the tune of “Under the Sea” in 1990, is still satirical — but less so than it was when it was added to the repertoire. In the seven years since Princeton said that it would get rid of loans and remove the value of the family home from aid calculations, the portion of each incoming class receiving aid has risen sharply, from 38 percent to about 54 percent — and the average size of those grants has more than doubled, to almost $31,200. Today the average financial-aid grant for a student from a family earning up to $100,000 a year is more than the $33,000 cost of tuition. Even students who would be considered quite well-off by most Americans get assistance: Among families applying for aid who earn between $150,000 and $200,000, 80 percent receive help — an average of $17,100.

Since Princeton’s 2001 policy changes, a host of other schools have introduced their own measures, including a flurry of recent moves sparked by Harvard’s announcement in December that even families nearing $200,000 a year in income may pay as little as 10 percent of their incomes for college. It all has lucky students and their families celebrating, and schools scrambling to keep up. “There’s quite a bit of pressure now to follow the moves that Princeton was able to make seven years ago,” says Robin Moscato, Princeton’s director of undergraduate financial aid. “In addition to no-loan packages, the trend now is for schools to improve aid for middle-income families.”

The ripple effect of these changes has yet to be fully felt or even imagined; most were announced after students applying for spots in the class of 2012 had sent in their applications, so the impact likely won’t be understood for at least another year. But college presidents, while praising anything that broadens access to higher education, also have their questions about the most expansive policies. Some worry that the trend toward greater aid for wealthier families will cause even the affluent to believe they have no obligation to save for or invest in a child’s college education. What will the new policies mean for the universities and colleges that implement them? What are the effects on schools that don’t have the money to compete with similar plans? And, more broadly, how do these changes affect higher education in general — will the poorest students get squeezed out if aid attention turns to the upper-middle class?“Anything that Princeton or Harvard does is going to make news; it will help us focus on a conversation that this country needs to have,” says Jennifer Raab *79, president of Hunter College, the largest college in the City University of New York system. As part of that conversation, PAW asked Princeton alumni who head colleges and universities, as well as other experts, for their thoughts and predictions.

First, let’s look the aid policies themselves. As Moscato says, some schools simply are replacing loans with grants in their aid packages, either for all students or for those from families earning less than a certain amount (which varies at each college). But a handful are doing that and much more. Under Harvard’s plan, families with annual incomes between $120,000 and $180,000 usually will pay just 10 percent of that in costs. Yale said in January that it would help families earning up to $200,000. Dartmouth, Brown, and other schools have announced so-called free-tuition programs, in which families earning less than a certain threshold pay no tuition at all. That’s not the term Princeton used to describe its 2001 changes, but the result is similar.

Eliminating loans is the more affordable step for colleges to take, and it’s also widely — though not universally — applauded. One obvious goal is to make sure that students don’t graduate with a burdensome debt (the average student-loan debt is now more than $20,000). A 2007 study co-authored by Princeton professors Cecilia Rouse and Jesse Rothstein found that an extra $10,000 in debt diminishes the odds that a graduate will take a public-service or other lower-paying job: “When students were relieved from the need to incur debt, they shifted toward lower-salary jobs in public-service industries,” the study found. Loans as a component of an aid package also disproportionately scare off lower-income students, whose families tend to be more uncomfortable taking on debt than middle-income families, aid experts say.

Though some schools have followed Princeton’s lead in eliminating loans for all students, most colleges simply cannot afford it. Princeton’s endowment — $15.8 billion at the end of the last fiscal year — enables the University to pay out more in financial aid than it takes in through tuition, but few others have that flexibility. A more typical college in this regard is Fairfield University, a Jesuit university in Fairfield, Conn, where the Rev. Jeffrey von Arx ’69 is president. “I came [to Fairfield] when we were meeting 75 percent of estimated family need; now we’re up to nearly 85 percent, and I hope to meet 100 percent. But some students get a financial-aid package that does not meet their total need, and they have to take out loans,” he says. “That’s when it’s important for us to be as brutally honest as we can and tell them that, given the package, they should give careful consideration to coming here. That’s a hard thing to say. But it’s the reality of the financial-aid market at 90 percent of places.”

Even at some of those schools for which such a no-loan policy might be an option, there’s caution. Michael Roth *84, the president of Wesleyan University in Middletown, Conn., often hears from distressed parents who are feeling the pinch of tuition. “We have to make sure we don’t become a school that has only the very wealthy and very poor people,” he says. “On the other hand, how do you judge an appropriate sacrifice? It’s very difficult, and we want to make sure we are using resources in as strategic a way as possible to make it possible for those who want to come here to do so.” After all, a school that uses its limited financial-aid pool to offer grants instead of loans probably cannot help as many families as it could if loans were part of the package. Roth announced in November that Wesleyan would eliminate loans for undergrads with annual family incomes of less than $40,000. Wesleyan is studying a more comprehensive no-loans program, but Roth believes that it’s not the only way to go. “We don’t want to be just chasing the schools that have gotten rid of loans; we want to study that more carefully over a year or two,” he says.

“I’ve lost track of how many schools have come out with statements saying that they’ve eliminated loans,” says S. Georgia Nugent ’73, president of Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, and former associate provost at Princeton. Kenyon will guarantee a loan-free education to 25 lower-income students with exceptional leadership potential starting in the 2008–09 school year, funded partly by a gift from alumnus Paul Newman — but Nugent, like others, is not convinced that this is the right approach for all students. “While I’m definitely concerned about the level of indebtedness that college graduates have, and we’re working to bring that level down, I don’t think it should be brought down to zero,” she says. “A message is being sent to the American public that higher education shouldn’t cost very much, and that you as a family or a prospective student shouldn’t have to invest in the future.”

Student investment is also an issue at Berea College in Berea, Ky., where Larry Shinn *72 is president. He leads a college that’s unique for its history and operation. Established to educate low-income students from Appalachia, Berea provides free tuition, though most students — 60 to 70 percent — require loans to pay for things like technology, study abroad, and living expenses. Shinn is proud that the average debt of a Berea student is only one-tenth of the national average. Still, he questions whether reducing loans to zero for everyone is the right thing to do. “If a student is guaranteed to have no debt when he or she leaves school, how much does he or she feel they’ve worked for their education?” he wonders. “Reducing loans so a student doesn’t graduate with $25,000 in debt and can be a public school teacher is very healthy. But it’s a bad idea to eliminate loans entirely; education then becomes an entitlement.” At Berea, that philosophy also applies to work: All students work 10 to 15 hours per week in approved jobs. (Princeton maintains a work requirement of 7.5 hours per week for freshmen who receive financial aid and 8.5 hours for everyone else — an hour-and-a-half less per week than students had to work last year. “We didn’t want students on financial aid to have a radically different campus experience in terms of activities,” explains Moscato.)

Aid to families earning more than $150,000 — statistically far above the middle class — is especially controversial, since many feel that money would be better used to promote access in other ways. (In a sense, even the wealthiest families already are being subsidized, since the true cost of an education at a top school is only partially covered by the tuition fee.) It’s not that college costs aren’t a problem; the sticker price for Ivy League schools hovers around $47,000. But some financial-aid experts predict even more pressure to get into the handful of elite schools that can offer the most generous aid. “Not only do people feel like these are the only institutions that count, but it will cost their parents so much more if they go elsewhere,” says Michael McPherson, former president of Macalester College in St. Paul, Minn., and now president of the Spencer Foundation, which funds activities that foster new ideas in education.

That realization could influence the spending decisions of schools that don’t have multibillion-dollar endowments, McPherson says. Such schools will have to weigh whether to redirect funding now targeted for other expenses — like professors, labs, and grants for low-income students, for example — to assist upper-middle-class families, perhaps by using grants based on merit and not financial need. While that has benefits in some cases, “if schools in the same pecking order start bidding for students, they end up with the same students and get less revenue from them,” he explains. “In some ways, the reasonable thing is to just say, ‘Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Stanford are on a different planet and have nothing to do with what we’re doing — they’re in a different game.’” The problem? “Empirically that’s more or less true, but the fact is that emotionally — and for trustees — it’s really hard to accept that,” McPherson says.

“Moving up the income scale will surely put the pressure on,” says John Strassburger *76, president of Ursinus College in Collegeville, Pa. “People think, ‘Gee, if Harvard will only cost us $18,000, why should Ursinus cost us $30,000? I don’t get it.’ The perceived costs of education will change.” To better compete for good students and sustain diversity, Ursinus will try to increase aid and cut loans for the best students in its pool next year, Strassburger says.

The pressure is not being felt solely by private schools with smaller endowments. Public colleges sometimes compete for the same students — with budgets that face even tighter constraints. In a February letter to members of the U.S. Senate Finance Committee, President Tilghman noted that most students now “pay less to attend Princeton than they would pay to attend the nation’s great public universities.” Indeed, after Harvard made its announcement, the chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley, Robert Birgeneau, wrote in an op-ed in USA Today that because private institutions can be so much more generous with aid, the latest moves may mean that “it could become more expensive for a student from a family of low or moderate means to attend a public university than for a student from a well-to-do family to attend a private college.” (Berkeley costs about $25,000 a year for out-of-state students.) To compete, he’s calling for public-private partnerships to fund endowments — and better financial aid — at public schools, which educate 75 percent of the college population. But state budgets are being squeezed everywhere, leading many to call for national help.

“Congress needs to say that this is such an important priority that we need substantial additional funding for financial aid,” says Mark Kantrowitz, creator of FinAid.org, which offers information and tips on paying for college. “An extra $10 billion to $15 billion a year would eliminate loans from most aid packages in the country and put Pell Grants [for low-income students] on a firm financial footing,” he says.

While the funding of public schools is a universal concern, some public-university presidents see the issue differently. Steven Poskanzer ’80, president of the State Uni-versity of New York at New Paltz, where in-state tuition is just $4,350 a year, says his school begins to look like a bargain compared to private schools that cannot offer extensive aid — and that might boost his enrollment.

Will the recent moves to expand financial aid promote greater access to higher education overall, especially for the poorest students? That’s a concern for many experts, including Donald Heller, director of the Center for the Study of Higher Education at Pennsylvania State University. “One of my major concerns is that the people who will get the short end of the stick are those from low- and truly middle-income families,” Heller says. “All of these institutions are doing a better job of encouraging people from these wealthier families to apply. If they’re successful, there will be even more competition for a fixed number of spots.” (Princeton is gradually increasing the size of its entering class over several years until it hits a projected total undergraduate enrollment of 5,200 in the fall of 2012.)

“While at a gut level, we presume that access for the lower socioeconomic level has improved, really it’s worsened,” says Nugent, at Kenyon. There’s a very great discrepancy between the percentage of upper-middle-class students who are able to go to college and that of students in the poorest group, she notes. The gap is greatest at the most selective schools: Students from the poorest socioeconomic quartile make up 3 percent of enrollment there, compared to 74 percent from the richest quartile, according to a Century Foundation study published in 2004. At Princeton, before the no-loan program was implemented, just 8 percent of the class was made up of students from families earning below the national median income for households with children, now around $55,000, according to Moscato. That has risen to 15 percent in the Class of 2011. But enrolling the poorest students has proved more difficult: About 9.5 percent of Princeton students now qualify for Pell grants, which have an income cutoff of about $45,000 per year (and are not available to international students), Moscato says.

Several of the alumni presidents note that financial aid alone cannot greatly increase the representation of poor students in higher education in general and elite schools in particular. All the aid in the world, they say, can’t make up for the diminished educational and enrichment opportunities throughout the K-12 years that often accompany lower socioeconomic status. To tackle college access in a serious way, Nugent, like many others, predicts that four-year colleges increasingly will forge partnerships with elementary schools, secondary schools, and community colleges to work on the more fundamental problem of college preparedness — which she argues would be a better investment than helping out the upper-middle class.

“There’s also the barrier of what a 17-year-old imagines he or she can do,” says Christopher Thomforde ’69, president of Moravian College in Bethlehem, Pa. “For a school like Moravian or an international university like Princeton, the question is how to help students get to college who couldn’t imagine going to college in the first place.” To that end, Princeton and other colleges, including Harvard, the University of Virginia, and Amherst (under the leadership of president Anthony Marx *90) have stepped up their efforts to reach out to lower-income students — and to offer greater support once they arrive.

“Places that are serious about access don’t just provide financial aid, but academic and other assistance to students whose poverty is not about dollars alone,” says Shinn, at Berea. “We must think about access in broader terms than financial aid.” (Such support might include assistance for students to take part in a university’s social life: A recent Princeton student-government survey found that students from wealthier backgrounds were more likely to join an eating club, and that lower-income students were more likely to refrain from purchasing course materials and to say that the added costs of extracurricular

activities were a barrier to participation. And for the 2007–08 academic year, Princeton increased the amount of aid grants for juniors and seniors to account for the average price of a club

membership.)

Kantrowitz predicts that the financial-aid announcements aren’t over. Respond-ing to rising tuition, Congress is keeping the pressure on, scrutinizing the endowments of the country’s richest colleges and universities, and many schools have said that they will dip further into their endowments for financial aid in the future. “Within a year or two, all the elite colleges that have very low-income students and very high endowments will have eliminated loans from the financial packages of low-income students,” he says. Others, he says, will follow Princeton in eliminating loans for all students.

And, he believes, some of the best-endowed schools may take the ultimate step and eliminate tuition entirely. Moscato says that families should pay if they are able — which means that Princeton, despite the popularity of the Nassoons’ song, isn’t likely to become free. But some college will do it, says Kantrowitz: “It’s the natural consequence of the competition for the top

students.”

Katherine Hobson ’94 is a writer at U.S. News & World Report.

2 Responses

Kenneth A. Bernhard ’78

10 Years AgoThe changing picture of financial aid

The May 14 PAW cover story raises an issue Princeton and our peer institutions must consider. Increases in the nominal tuition at the most heavily endowed colleges and universities drive up tuition elsewhere, thereby saddling many excellent students at other colleges with excessive debt.

The full tuition charged by Prince-ton and comparable universities sets the upper limit for tuition at many excellent but less affluent schools. We have traditionally viewed our tuition and financial-aid policies as a legitimate form of income redistribution, but this has an unintended consequence. Other colleges raise their tuition in tandem with ours. With less generous aid programs, their students are assuming increasing debt loads, often in the form of private, nonsubsidized loans. Such loans typically accrue interest while a student is in graduate school, postgraduate training, or public service.

I agree that families and students should invest in education (with two daughters in college, I am investing a good deal myself). However, I fear that the magnitude of student debt, and its impact, is underestimated by many of those who set tuition. As a cardiologist, I have the privilege of interacting with housestaff who recently have finished medical school. Their debts are often in excess of $200,000. Similar debt loads afflict students in other fields of graduate study. This seriously impacts student career choices. Students are compelled to seek high-paying jobs in order to get out of debt, regardless of their field of endeavor. Such debt also impairs young adults’ ability to save for their retirement, and for their own children’s education. By allowing student debt to explode over the last several decades, we may be laying the groundwork for a future debt crisis.

Princeton and her peers should not only continue our generous aid policies, but also take the lead in attenuating the ongoing rise in tuition. I am enormously proud of Princeton’s aid policies. I have contributed to Annual Giving every year since my graduation, and intend to continue doing so. My hope is that Princeton and her peers, by restraining the rise in their tuition, might aid many fine students at other excellent, but less well-endowed, colleges. As we set our tuition and financial-aid policies, we should be cognizant of the impact of our actions on others.

David Tobin *77

10 Years AgoDavidson's financial aid

Your article on “the recent spate of financial-aid improvements” ignores the significant role played by Davidson College. In March 2007, Davidson became the first liberal arts college in the country to replace loans with grants in all of its financial-aid packages. With an endowment roughly one-fifteenth that of Princeton’s, Davidson’s courageous decision is far more relevant to most schools. (Full disclosure: I am the proud father of Josh Tobin, Davidson College Class of 2010.)