The ship of Theseus is a timeless thought experiment: If you replace every part in the ship with a new part, is it the same ship?

So it is with Firestone Library. It’s marking its 71st birthday this year — and also a rebirth.

A decade after work began, the renovations to the library are complete. “The entire library was touched — the entire library — it was a gut renovation, down to bare concrete walls and ceiling,” says Jeffrey Rowlands, the director of library finance and administration, who oversees library facilities. “Every single square inch of this building, including all of the mechanical spaces — everything was touched.”

If you haven’t set foot in Firestone in a while, it might feel like a completely different building. Though the footprint of the 430,000-square-foot building (three-quarters of it underground) was not expanded, there are new spaces, new applications of technology, and new lighting that make the building feel airier, more inviting, and more conducive to study. (One additional incentive for students to spend time at Firestone remains under construction: the Tiger Tea Room, which is expected to open in late June.)

Renovations took almost 10 years to complete because Firestone had to remain open — and quiet — during the entire construction period. The overhaul was expected to cost $165.6 million, according to an economic-impact statement released by the University in October 2016 (more recent figures were not released). The executive architecture firm, Shepley Bulfinch, describes the new Firestone as “an open and flexible laboratory designed to keep pace with future demands in humanities research.”

It’s been somewhat of a passion project for President Christopher Eisgruber ’83. He was closely involved with the planning while he was provost, visiting other renovated university libraries with faculty and library staff. “On those trips, I learned that libraries express the scholarly character of individual campuses,” Eisgruber said in a statement. “That is very true of Firestone. ... Our Firestone has always been a powerful laboratory for the humanities and social sciences; it is now also a beautiful and inspiring home for scholars and the books they love.”

The library remains rooted in its history. When Firestone opened in 1948 — the first large American university library constructed after World War II — PAW called it innovative, thoughtful, and even a place of “miracles.” It had a different look than most university libraries, with a gothic revival exterior but an industrial, art deco look inside. The goal of designers working on the just-completed renovations was to “retain the DNA” of that building “and to bring it into a contemporary learning, teaching, research environment,” says design architect Frederick Fisher.

As a result, amid the technology and modern design of the new library you will find frequent nods to the past: The old card-catalog faces have been transformed into floor-to-ceiling wall art; three original metal study carrels remain among the rows of stylish open ones; vintage stereoscope viewers occupy a large glass display case near the collection of rare books. The new mid-century-style chairs and sofas placed throughout the library evoke the period of Firestone’s construction.

“One of the things that intrigued me about it is it does have these different layers to it that are seemingly contradictory but, I think, add a richness to it,” Fisher says. “The intellectual basis for our approach to the project ... was preserving the essence of the building and modernizing it, rather than erasing all those layers.”

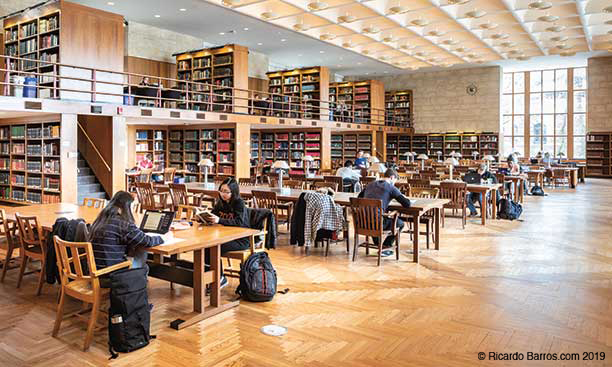

The first thing a visitor notices upon entering the “new” Firestone is the light. The wooden paneling remains, but the place seems suddenly bright and open. Overhead in the lobby is a massive LED light, reminiscent of an oculus. Throughout the building, study spaces take advantage of natural light. Where the card catalog once was, there is now a sleek black information desk, students sprawled on a collection of sofas and chairs, and a long bar-height counter where students sit on stools, typing into their laptops. To the right is a “Discovery Hub,” a large, open space with work tables of different sizes, plus shelves of newspapers and books written by faculty members.

The light and sense of openness continue as one descends underground. Once-forbidding rows of bookshelves are now welcoming, with lights automatically brightening as you walk through the stacks. Before the renovation, the building was “extremely brown and very dark,” says University Librarian Anne Jarvis. Now, she notes, it’s a warm environment with a variety of spaces in which people can work.

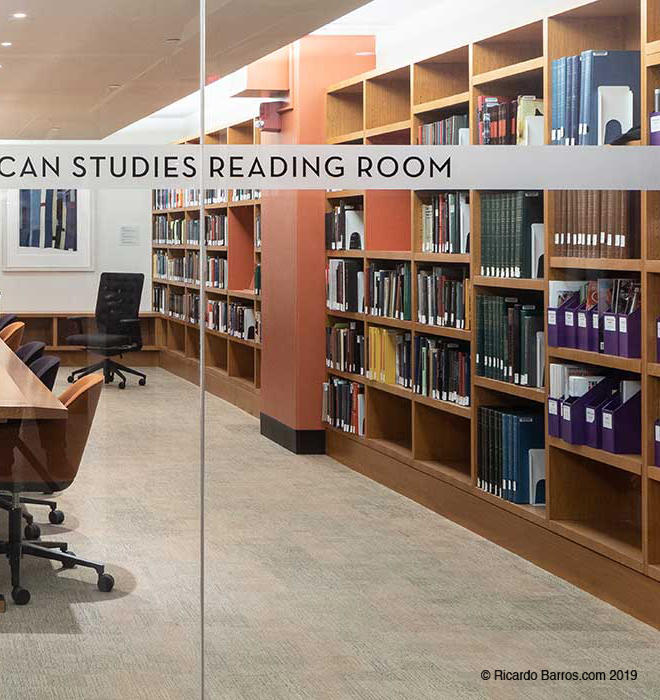

Fisher says he has a “real obsession” with light because it’s one of the biggest contributors to a person’s comfort. As a result, skylights were installed — most notably at the top of the main stairwell — and offices were moved inward from the perimeter, so the windows would be in communal spaces. Instead of installing solid walls throughout the building, Fisher opted for glass partitions in many places to maintain a sense of openness.

Easier navigation was another renovation goal, and the designer used light and color to help visitors orient themselves. The building’s color palette changes throughout the building to give visitors an indication of where they are. Bookcases run from north to south, with the south end painted a lighter shade and the north end a darker one. “It’s almost like a shadow,” Fisher says. “When you look down an aisle, you intuitively understand where’s the north and where’s the south, and it keeps you oriented because when you’re down in the bowels of the building, it’s hard to really keep track of which way you’re going.” Signs also help visitors find their way.

The renovation of Firestone was sparked partly by technical demands: Fire-suppression and electrical systems had to be updated by law, and the University wanted the building to be more energy-efficient, Rowlands says.

At the same time, the University wanted to better embrace technological advancements. “We are moving beyond the concept of a library as a finite place with traditional collections to that of a library as a partner in research, teaching, and learning,” Jarvis says. The Data and Statistical Services Lab offers help in analyzing data, and the new digital-imaging study allows greater digitization of the library’s vast resources. “What the digital environment helps to do is to make our collections more discoverable,” which facilitates more national and international research, Jarvis explains.

“There are lots of things that have been designed to enhance this environment to meet those 21st-century needs,” Jarvis says. “But, you know, I’m a librarian through and through. There’s nothing like the look, feel, and smell of the original.”

Printed books — there are about 2 million in Firestone, not including rare books — are still prominent. A conservation lab preserves and maintains the library’s rare books and circulating collections.

“One of the guiding principles was to keep the same number of books in the building after the renovation as before,” says Rowlands. “It’s not just about the book you find in the catalog; it’s about all the books all around that book on the shelf that you discover while you’re out browsing.”

Ideas for reorganizing the spaces in Firestone grew out of meetings with students, faculty members, and library staff — and among the things students wanted were more and different kinds of study spaces. They got them: the gorgeous William Elfers ’41 Reading Room, with a massive new tapestry by John Nava; the “Tower” study space, which feels like a sanctuary; special study spaces for graduate students and different disciplines, strategically located near the resources those students and scholars would use. Group study and research have become more popular, and the new spaces allow students to work “on their own together,” Jarvis says: “We’re providing spaces for our students to come together, to create together, to innovate together, to bounce ideas off each other.”

Researching Firestone’s history, Fisher found old photographs of Firestone in which there were islands of study areas interspersed among the bookcases, and he wanted to re-create those. “It encourages people to stop and find a place, near where they’re trying to find a book, to study,” he says.

Fisher aimed to make students feel at home in the study spaces, choosing carpets, couches, fabrics, and artwork to domesticize and personalize what could be considered an institutional building. “We wanted them to feel comfortable and bring an intimacy, which in a way is almost contradictory to an enormous building like that,” he says. “We made an effort to create many varied, intimate environments with a particular kind of furnishing to, in a way, change the overall feeling of the building from the so-called institution to the home.”

Designers also worked to make Firestone a greener, energy-efficient building. The motion-sensing and LED lights save energy, the HVAC system was upgraded to use “chilled beam” technology, new windows are thermal insulated, and the bathrooms now have low-flow plumbing.

Rowlands notes that workers were able to recycle or repurpose a significant amount of the materials that were taken out of the building, including concrete, wood, electrical wiring, and copper, among other materials. (Contractors also found old notebooks, complete with drawings and references to the Honor Code, a pipe that still smelled of tobacco, empty bottles of beer, an origami crane from 1969, and other relics — some of which the library displayed in a 2013 exhibition called “Building Firestone.”)

“Princeton has this great legacy, and they will continue to have this great legacy in the future,” Fisher says. “We were very interested in doing something that would have a timeless quality to it, and not be just a design fad that would look cool for a few years and then look dated. That was part of going back to the original DNA of the building.

“My hope,” he continues, “is that the library will be used in a way in which these successive generations can imagine new pursuits that we can’t even imagine.”

Anna Mazarakis ’16 is a podcast producer.

4 Responses

Birgitta Ingemanson *75

6 Years AgoMajor Repairs

The article about Firestone Library this spring reminded me of the following notes by the elevator that I wrote down in January 1971:

During the move into Firestone Library's new addition, it took a long time for the elevators to return to action again. Several months earlier, the following notice had been glued to the doors: Out of Service Indefinitely for Major Repairs.

Whereupon, little by little, in many different hand-writings, the following bits of wisdom were added:

Tell Major Repairs that General Use wants this damn thing back in service immediately.

Major Repairs is out with Private Parts.

I don't want to hear anything more about Admiral Puns.

Anyone writing here will be subjected to Corporal Punishment.

Kernel Truth is here somewhere ...

Inane, perhaps, but any level of humor brightens up one's labor over books, in carrels!

Dick Williams ’62

6 Years AgoFirestone’s Sense of Peace

I did a great deal of my schoolwork in what PAW refers to as the Trustee Reading Room and we called the Library.

The look and feel of the “reborn” Firestone (cover story, April 10) is delightfully the same as I enjoyed from 1958 to 1962, which provided a wonderful sense of peace to punctuate the intellectual endeavors of lectures and precepts and the physical challenges at the basketball and tennis courts.

Thanks for the memories.

Bob McCarty ’55

6 Years AgoKudos for Coverage

The library coverage was very well done. PAW, both online and the PAW magazine, are more relevant, better designed, and always welcome.

Thanks for your efforts.

David Hochman ’78

6 Years AgoFirestone Memories

At the time of my last big reunion, I saw the renovation of Firestone in progress, and it was nice to read it is now complete. Viewing the photos brought back memories of certain experiences it would be impossible to preserve through artifacts of a kind that have been preserved.

For me, one such memory involves the elevators just off the entry lobby. Students rarely used them as lifts, but some nights, you could find a special breed of undergraduate hunched in the corner of a Firestone elevator grasping . . . a telephone receiver.

At that time, the elevator emergency-communication system was a simple dial phone connected to “Centrex,” the internal system through which we could make intra-campus calls free of charge. At our offices at 48 University Place, Prince reporters used Centrex all the time to reach students, faculty, or University administrators we needed to interview.

Unless assigned to a story or sports event that ran late, Prince reporters typically finished and handed in their stories to the editors before dinner time. We went off to eat, but we weren't done yet. We were also responsible for writing our own headlines. A headline had to be clear and accurate, and it had to "fit" the layout. The trouble is, the layout editor was rarely finished by the time we’d checked out. Usually the layout was done by about 7:30 or so, and so we’d have to get back in touch around then to get the character count so we could write our headline in time for production deadlines.

I suppose some reporters called in from their dining facility or from back in their dorm rooms, but student journalism had put me pretty far behind on my studies, and I was often in Firestone catching up. Using a trick our elders taught, I’d head to the Firestone elevator, grab the Centrex phone, call in for the “count,” curl up on the floor with a notebook and take a few minutes to work out the right words and character count, and finally call the Prince back to phone it in (literally). Sounds silly, but it worked, and I could get back to nerding with minimal disruption.

Sometimes ordinary library patrons or even the proctors would find us talking to the emergency phone and ask if everything was OK. But most nights that I had to do this, I was uninterrupted.