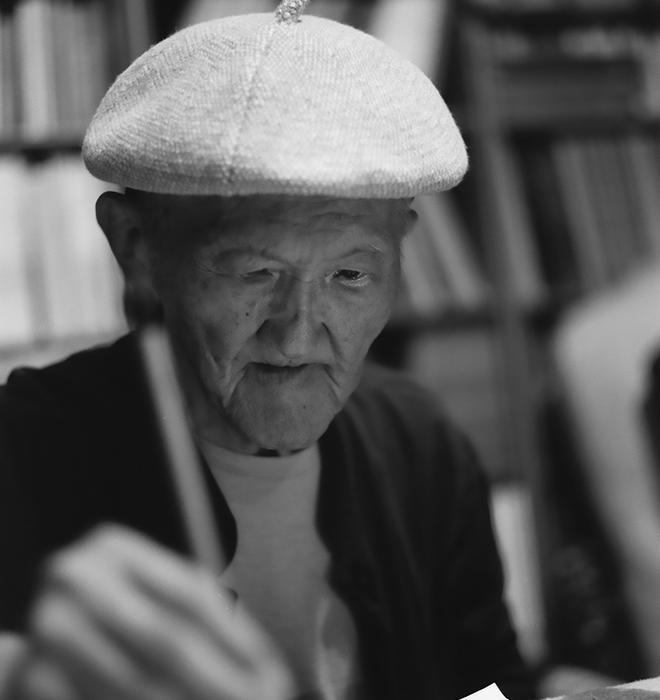

Fu Shen *76 Was a Prolific Scholar and a Gifted Artist

‘Today, there are people who claim connoisseurship who have not seen one-tenth of the number of paintings as Fu Shen’

Fu Shen was born in 1937 in Shanghai, but with China on the brink of war with Japan, his parents sent Shen to live in the countryside with extended family two weeks after his birth. “My early experiences were mostly of farmland and small rivers,” he said in a 2018 speech. “At that time, I thought my future would involve farming.”

Shen found a different future in the countryside. His uncle was a calligraphy enthusiast, and as an elementary school student, Shen became his “service boy,” grinding ink and practicing calligraphy alongside him. When the war ended in 1945, Shen returned to his parents, who moved to Taiwan. He matriculated at Provincial Normal University and studied art despite his father’s wishes that he pursue a more traditional career. Shen graduated in 1959, winning prizes in calligraphy, painting, and seal cutting.

In 1963, television was new in Taiwan. The Taiwan Television Corp. created a calligraphy instruction program, and Shen was chosen to teach calligraphy on a live broadcast for 20 minutes a week. He taught for 10 months, until he joined China’s youth cultural delegation in Africa as the accompanying painter. In the role, he spent time in many African countries, curating contemporary painting and calligraphy exhibitions.

In 1965, Shen joined the newly opened National Palace Museum in Taiwan as a research scholar. He was given the monumental task of cataloging thousands of works that had been evacuated from mainland China in 1948 during the Chinese Civil War.

“That experience gave him a foundation that very few connoisseurs have,” says Stephen Allee, a curator at the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art. “Today, there are people who claim connoisseurship who have not seen one-tenth of the number of paintings as Fu Shen.”

In 1966, Marilyn Wong *83, an art and archaeology Ph.D. student at Princeton, arrived in Taiwan to complete an internship at the Palace Museum. A year later, she and Shen wed, and shortly after that moved to Princeton when Shen was named a John D. Rockefeller III fellow.

At Princeton, Shen made some of the most important contributions to the Western study of Asian art to date. He worked with Wong almost daily on the second floor of Marquand Library. “We would hole up in Marquand,” says Wong. “We almost used to spend the night there.”

As Shen’s English was still limited, he would speak to Wong in Chinese, and she would translate as she typed on an electric typewriter. They co-authored Studies in Connoisseurship, published in 1973, in which they introduced a method for using connoisseurship to authenticate and date works of calligraphy. In other words, a formal process by which individuals with extensive and specialized knowledge could identify and study works with a combination of expertise, intuition, and visual memory. The work was groundbreaking.

After completing his Ph.D. at Princeton in 1976, Shen taught at Yale. He was known as a demanding and devoted professor, beloved by his students. Sometimes, his classes lasted up to six hours. Once, he accidentally gave an assignment with a due date on Thanksgiving. When the students reminded him of the holiday break and that the building wouldn’t even be open, he replied that he couldn’t believe they would consider taking time off instead of coming to class. He and Wong ended up hosting the students at their home. They served a Thanksgiving duck.

In 1977, Shen curated “Traces of the Brush,” an exhibition of Chinese calligraphy and paintings at the Yale University Art Gallery. It is regarded by many in the field as the most important exhibition ever of Chinese calligraphy in the U.S. In 1979, Shen moved to Washington, D.C., where he served as the director of the Chinese art department of the Freer Gallery of Art until 1994.

Shen was a prolific scholar, but he was also a gifted artist. “Even if he wrote something very simple, like a laundry ticket, all of those years of training would come out,” says Wong. “And he had a manic love for visuals. You could show him a tiny corner of a painting and he could identify it correctly.”

Jake Caddeau ’20 is a freelance writer and filmmaker.

No responses yet