The Future of Journalism: Covering Campus

Princeton’s student-journalism tradition marches on

The offices of The Daily Princetonian occupy the first and second floors of a red-brick building on University Place. They were renovated by the staff in the fall of 2018, so they no longer have the air of gentle dishevelment that you might expect from a place where college students publish a newspaper.

The process of editing and designing the paper takes place in a brightly lit L-shaped room, where rainbow pennants crisscross the ceiling and blown-up printouts of historic headlines cover the walls. Soft brown couches have been replaced by armchairs so shiny they look laminated. Hardbound volumes of Prince issues have been removed from a cluttered upstairs room, long referred to as the “Chamber of Secrets,” and are now tidily arranged on shelves downstairs.

Those volumes date back to 1876: the year Colorado became a state, Alexander Graham Bell made the first telephone call, and the Princetonian started churning out copies from a corner office in Dickinson Hall. Its inaugural edition included an editorial attack against hazing, with grim references to “nightly visits” and “cane-sprees,” and a report that the year’s matriculating class broke records as Princeton’s largest ever, with 160 students. By the end of the century, the biweekly Princetonian had become a daily.

Since then, the publication has been a fixture of Princeton life, a journalistic witness to nearly every major event that has swept across campus. It was there when Woodrow Wilson 1879 was elected U.S. president and when Fidel Castro, visiting for a lecture, gave an impromptu speech to a crowd of students on Washington Road. It was there when Albert Einstein arrived in town in 1933 and when Firestone Library, Dillon Gym, and Wilcox Hall were designated as nuclear-bomb shelters in 1961. It was not there for four months in 1919 and three years in the 1940s, when wartime rationing and a loss of manpower to the U.S. Army forced shutdowns. But it came back. It has continued to operate financially independent of the University, funded primarily by ad revenue and print subscriptions. Today, the Prince is the only daily print newspaper published in the town of Princeton and the five towns that surround it.

Chris Murphy ’20, The Daily Princetonian’s 143rd editor-in-chief, is sitting in his large first-floor office, a room decorated with old copies of the paper and a row of drinking glasses emblazoned with the Prince logo. Murphy is dressed in khaki pants and wrapped, somewhat surreally, in a wizard’s cloak — it is the night of Princetoween, and Murphy’s bright red hair makes Ron Weasley a fitting costume choice.

Murphy had never written an article when he joined the paper as a sports writer in his freshman year, but the dynamism of reporting quickly appealed to him. He remembers getting a call from then-editor-in-chief Do-Hyeong Myeong ’17, who asked him to “get in a car and go to Buffalo”; the next week Murphy was sitting courtside at a March Madness game where Princeton lost to Notre Dame by two points. As an upperclassman, he edited the sports section and eventually ran unopposed for the top editor position.

Being Prince editor is less like being the president of a club and more like working an unusually demanding and unpredictable part-time job. There are weekly staff meetings, quarterly meetings with the paper’s trustees, and a more or less constant stream of emails and messages throughout the day. Then there’s production.

A typical night of production at the Prince’s office goes something like this: At 5 p.m., section editors arrive at 48 University Place and begin reviewing articles. After editors make comments, the draft is sent back to the writer, who updates it and sends it back to an editor, who uploads it to the Prince’s online-publishing software. These relays zing back and forth for the next three hours and are still going on when Murphy arrives around 8.

Murphy says the paper’s most formidable current challenge is adapting to digital publication, especially social media.

By then, the copy desk is crowded with staff members scouring articles for errors. Two or three design staffers are hunched around a double monitor, arranging advertisements and headlines on a mock-up of the print page. Photographers are dropping off the Nikon cameras they use for their assignments, and new writers are reviewing line edits with their editors. Others are making a U-Store run to buy pretzels or doing schoolwork with their headphones on. The chaos continues until midnight, sometimes later — until whatever time Murphy does a final check on the pages and sends them, electronically, to a printing press in Philadelphia. Early in the morning, a group of students, hired by the business team, delivers stacks to dining halls, eating clubs, offices, and distribution boxes scattered around campus.

Long and late nights in the newsroom are standard for Prince editors. Most work 15 to 20 hours a week; Murphy puts in 25 to 30. But these hours also reinforce the Prince’s sense of community, Murphy says.

He recalls a night of production last February. The news team was breaking the unusual story that someone, under cover of darkness, had unscrewed Tower’s front door from its frame and roped it to a bike-route sign at the end of Prospect Avenue. Murphy says staffers spent most of the night trying to decide on the perfect pun for a headline (the final choice was “Unhinged: Tower entryway adorns street sign”) and to make the article as comically straight-faced as possible (“Tower president Aliya Somani ’20 was aware of the door’s displacement and claimed to be working with staff to bring the door back by around 10 a.m.”)

“For me that [night] exemplified the vision I want to see of the Prince,” Murphy says. “This community that does a lot of great work but also can have fun together.”

In 1976, Prince alum John W. Reading ’67 published a reminiscence about the paper’s “hot lead days,” the era from the 1920s to the 1960s when workers operated a letterpress printer in the back room of the Princeton Herald, a community weekly. Editors wore ink-stained clothes and nursed metal burns, Reading wrote, the room thick with “clattering Linotypes, rumbling presses, odors of cigar smoke and printer’s ink.”

The hot-lead days may have ended decades ago, but at least some editors agree that paper and ink remain crucial to the Prince’s identity. “I think that when people think of the Prince they mostly think of the print newspapers that you can find in the dining halls, in res colleges,” Murphy says. Head opinion editor Cy Watsky ’21 grew up in Princeton, and he says that his parents and other adults in town walk to campus and pick up a copy each morning.

If the print paper remains central to the Prince’s image, the steady ascendance of digital news has reshaped the way people read it. Most Prince traffic comes from Facebook, and, to a lesser extent, from Twitter, where its @Princetonian account has roughly 14,000 followers. In recent years, the paper has placed a greater focus on these social-media accounts, created a video section, and revamped its website. Murphy says digital coverage helps the Prince break news more quickly and spread it farther beyond campus on social media.

But the internet has posed problems for the Prince. When students can access The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Facebook with a few swift strokes on a screen, the Prince has competition as a source of reading material. Few people are seen reading the print Prince while they eat in the dining halls, though more students stop to leaf through it outside. While the paper distributes 2,500 print copies per day, its website gets 30,000 online impressions per day and 30,000 unique visitors per week.

The challenges of digitization — relentless news cycles, shrinking ad revenue — have become familiar to publications both large and small; the Prince, says business manager Taylor Jean-Jacques ’20, is not an exception. Its largest revenue source continues to be print advertising purchased by student groups, campus departments, and businesses, but in the last 30 years, revenue has declined. To cope, the Prince has had to generate new sources of revenue, primarily through online advertising as well as a digital donation platform that Jean-Jacques’ team created this year. The paper retains a reserve for “emergency situations,” Jean-Jacques says, adding that the Prince’s current operations are fully funded from annual revenue.

Murphy says the paper’s most formidable current challenge is adapting to digital publication, especially social media. But he adds that the Prince has no plans to go all-digital or to cut back on issues. This commitment puts the Prince in a shrinking minority among national collegiate papers. A recent survey by the College Media Association found that 35 percent of student newspapers have reduced the frequency of print issues in the past year.

The same survey reported an uptick in student interest in journalism, and the Prince’s swelling staff reflects this trend. With 175 students involved — nearly half of them recruited this fall — the paper is one of the largest organizations on campus.

Students join the Prince for a range of reasons. Some are seeking a social community or a way to learn about campus; others a public platform to express their views (the opinion section’s recruitment tagline is “Don’t whine, opine”). Many students who are interested in collegiate journalism see the Prince as a straightforward choice, an opportunity for boots-on-the ground reporting without the literary tilt of the Nassau Weekly or the professional focus of the Press Club.

“We are the school’s newspaper. Period,” says Benjamin Ball ’21, the top news editor. “So if you want to work for a daily paper, we’re where you work.” Ball works with three associate editors to manage a staff of 60 news writers.

Ball joined the paper to sharpen his writing style; he describes his first semester as a “detox from adverbs.” But if his initial intent was academic, he soon “fell in love” with the paper and the lifestyle of a student journalist. By the end of his freshman fall, he was regularly staying in the newsroom until midnight and churning out five stories a week. In his sophomore year he reported on events ranging from a free-speech demonstration to the time a deer ran, skittering and bewildered, through a window in Wu dining hall. (His favorite published sentence is: “The deer had some difficulty descending the staircase.”)

We’d like to hear your stories about reporting for Princeton publications. Post a comment or email us at paw@princeton.edu.

As editor, Ball says he encourages the staff to “focus on the stories that we know either the student body cares about or the student body should know more about.” This means that coverage has shifted to include fewer reports on lectures and more articles that connect the University to broader trends, often focusing on professors and alumni who influence national or international issues.

Murphy says the paper has a good relationship with the University’s communications staff, though it sometimes can be difficult to get information from administrators. In the spring, the Prince covered the student protests over University Title IX policy. It was an eventful and emotional week. “There were four different editors, one photographer, and one video editor around at all times during the week,” Ball remembers. “The communications office and administrators appeared very on edge to me that week — I have a feeling we weren’t the only publication constantly bothering them.”

Murphy adds that contentious stories are sometimes the Prince’s best, as long as its journalists are fairly soliciting the perspectives of all involved. “Those dynamic stories that make people feel uncomfortable and challenged — those are the most important stories that we need to publish,” he says.

Murphy, whose term ends this month, tried to make the Prince less predictable and more professional. He invited former Prince staffers back to teach workshops, soliciting advice from alumni with long careers and younger graduates who know the digital ropes. Managing editor Jon Ort ’21, who was elected to take over from Murphy, ran on a platform that emphasized digital engagement — including plans to create a new app — and working with alumni. He also plans to continue publishing special editions that focus on a single topic, such as campus activism or gender equality.

Ball recalls working on a 2018 special issue as his most memorable experience at the Prince. With Ivy Truong ’21, he wrote an article on coeducation — “How Women Became Tigers” — sifting through archival documents in Mudd Library for hours and reconstructing 1960s debates over accepting female students. On the night of production, Ball arrived at the newsroom at 4:30 p.m. and stayed until no one remained but then-editor-in-chief Marcia Brown ’19. It was past midnight when a worker at the printing press in Philadelphia called to say the middle fold of the 16-page edition was jamming and printing had stalled. It was a tense evening, Ball remembers: Brown kept calling to check whether the pages were going through, and the two of them worried and even prayed together.

Hours later, they got the call they’d been waiting for: The pages were skimming along the press’s rollers. Then the two walked back together through the spring night to their dorm rooms. The campus was quiet, and the paper would be delivered as soon as night turned into morning.

News With Views

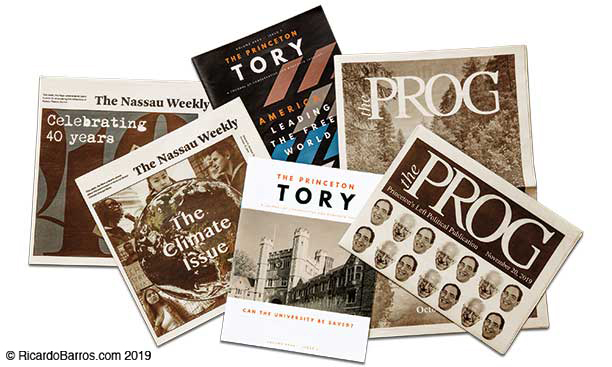

In addition to the Prince, Princeton students put out three other publications in print: The Nassau Weekly, the conservative monthly The Princeton Tory, and the progressive biweekly The Princeton Progressive.

The Nass publishes long-form news stories in addition to poetry, fiction, personal essays, and satire. Editor-in-chief Serena Alagappan ’20 says The Nassau Weekly’s journalism frequently puts more personal spins on campus issues. As an example, she notes coverage of the Title IX protests: The paper published a personal essay by Ellie Maag ’19 in late July, after the protests were over and Maag had graduated. “One of the benefits [the piece] had was the months of time to reflect and process and meaningfully address an issue that was really complicated,” Alagappan says.

Since its founding 40 years ago, the Nass has been one of the most visible examples of journalism on campus; it is distributed in campus buildings and dining halls. But the paper — which receives funding from the Princeton-based radio station WPRB 103.3 FM — faces diminishing revenue from print ads even as its online readership has expanded to 20,000 monthly hits. Last year, as they marked the paper’s 40th anniversary, Nass editors launched a fundraising drive and published a letter in PAW asking for alumni help in “restating our commitment to print journalism.”

Both the Prog and the Tory persist in print as well. Each has experienced a surge in energy in the past year.

Jeff Zymeri ’20, a former Prince editor who now leads the Tory, established a news section at the Tory last fall. “I saw that there was probably a certain set of stories that were not being covered as thoroughly by the Prince and by some of the other magazines and newspapers on campus which do news, and those stories had to do with conservative organizations and moderate organizations,” Zymeri says.

He kicked off coverage with an investigative piece on Whig-Clio’s decision to disinvite a controversial, conservative law professor, Amy Wax, in September 2018. (She did appear at a subsequent Whig-Clio event, generating more controversy.) Among other things, the Tory recently covered a campus lecture by federal judge Amy Coney Barrett. The Tory has a core staff of seven writers and a total membership of about 30 students.

The Prog has also gone through recent changes, says editor-in-chief Beatrice Ferguson ’21. In the past year, its staff size has doubled — it lists about 30 staff members on its masthead — and transitioned from publishing in print once a semester to once every two weeks. An October issue included articles on gerrymandering, climate “insurrectionists,” and the Jewish left on campus.

Allie Spensley ’20, PAW’s Student Dispatch writer, is majoring in history.

2 Responses

John Wilheim ’75

6 Years AgoChecking the Box

A Daily Princetonian remembrance for your collection:

My freshman year, 1971–72, was the last in which the Prince was produced using “hot type,” at a print shop on Witherspoon Street. Students set, by hand, all headlines of at least 24 points, while smaller headlines and text were set on a Linotype machine, which punched letters into slugs of lead.

The following year, staff members were asked to return to campus early to learn how to operate two new “cold type” machines that had been installed on the third floor at 48 University Place. One machine read punched tape and generated galleys of text; the second produced headlines, typed on its keyboard. Both required special coated film that was fairly costly.

In addition to writing sports stories for the Prince, I wrote and edited the program for men’s hockey games. This required working in the production room on Friday nights with Larry Dupraz, the paper’s compositor and father figure.

One warmer-than-usual night, we had the windows open and a friend of Larry’s saw the lights were on. He shouted up, and Larry invited him in to see the fancy new typesetting equipment. As he demonstrated the headline machine, Larry explained that it also could do special characters, including a check mark and a box. The friend asked, “Can you put the check in the box?”

Over the next few hours, Larry must have used more than $100 worth of the special film while figuring out the best method to do so.

Larry composited all the display ads for the Prince. For the next three or four weeks, there was at least one ad each day that featured a check in a box, all perfectly centered and pleasingly proportioned.

I kept in touch with Larry for the rest of his life. And each time we talked or met, invariably he would ask, “Did you put the check in the box?”

Lori Irish Bauman ’81

6 Years AgoLate Night at the Prince

Responding to PAW’s call for memories of student journalism (PAW Online email newsletter, Jan. 7), here’s a story from my time as an editor for The Daily Princetonian:

I started as a reporter for the Prince in September 1977, the fall of my freshman year, and served as features editor from January 1980 to January 1981. A recent New Yorker profile of my classmate and fellow Prince editor Justice Elena Kagan ’81 describes how she was drawn to “the adrenalized, proto-professional atmosphere of The Daily Princetonian.” The excitement often translated to long days and nights in the Prince offices on University Place.

Student activism at the time focused on opposition to apartheid in South Africa and to the University’s connections to companies doing business there. On a Sunday evening in March 1980, I was working as a night editor assembling the next day’s paper. At 10 p.m. calls — landline phone calls! — came to the newsroom with reports that a sit-in was starting at Firestone Library. As reporters hurried to the scene, the small group of us in the composing room took apart the paper’s layout to make room for coverage of the so-called study-in.

Reporting continued for hours as 80 protesters from the People’s Front for the Liberation of Southern Africa stated their intention to stay all night. University administrators arrived on the scene and warned of disciplinary consequences for the students who refused to leave Firestone at closing. Finally, at 2 a.m., we had to finalize the paper for printing, and a few hours later the Prince was delivered all over campus with the lead headline, “People’s Front stages Firestone sit-in.” I made it back to my room in Dod Hall not long before sunrise, only to be awakened at 9 a.m. to loud chanting when the protesters finally left the library and joined 50 other students for a rally on Cannon Green.