The Future of Journalism: War Stories

Can better journalism make Americans care more about the battles fought on their behalf?

Army Capt. Travis L. Patriquin, 32, of Texas, and Army Spc. Vincent J. Pomante III, 22, of Westerville, Ohio, died Dec. 6, 2006, in Ramadi, Iraq, of injuries suffered when an improvised explosive device detonated near their Humvee during combat operations.

How many times have we read blurbs like this over the last 17 years of the “War on Terror”? It would be almost impossible not to grow desensitized to them, as the troops are anonymous and the headlines numbing in their regularity.

Travis was a friend of mine — a supremely talented, larger-than-life one at that — and yet no one back home, save perhaps his family and close friends, would have had any idea how special he was, and how remarkable his contributions in Iraq were, based on news releases like this.

So let me tell you about him.

When I first met Travis, serving alongside him as a fellow infantry officer stationed in Germany, I was impressed by his intellect and irreverent humor. He liked to share some bratwurst and hefeweizens after a tough day. I admired his approach to life: He had seen combat and knew what was important and what wasn’t. As we prepared to deploy to Iraq, he shunned busywork and attempted to enjoy every last moment with his wife and young kids before he’d say goodbye to them.

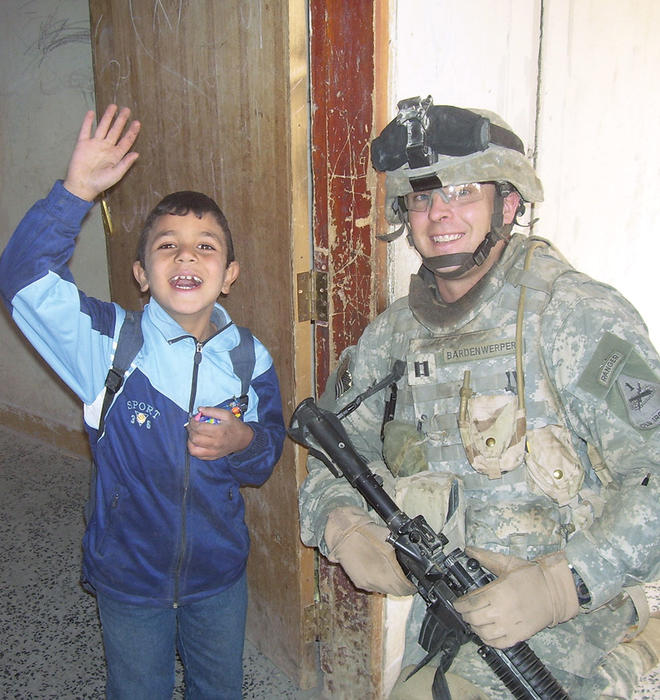

Above: Will Bardenwerper ’98 in 2006 with a student at a school in Hit, Iraq, where soldiers provided school supplies.

It was in Iraq where he really shined, using his charisma and fluency in Arabic to win over Sunni tribal sheikhs who had once been trying to kill us. Travis’ tireless drive and personal diplomacy contributed more toward the security of Anbar Province than entire companies of troops could have. One Iraqi sheikh even adopted Travis into his tribe and nicknamed him “Hisham,” after the prophet Mohammed’s great-grandfather.

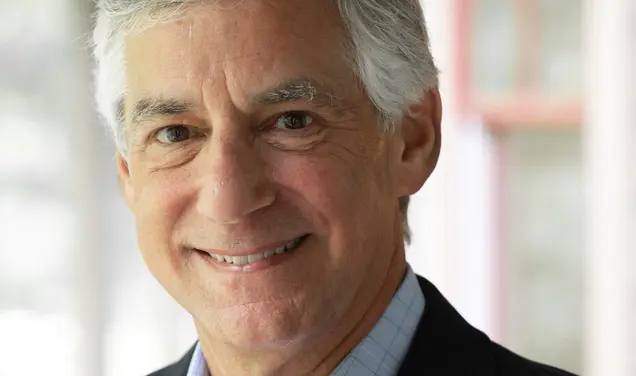

After my Army service and subsequent time as a civilian in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, I decided to pursue writing full time, publishing a book about the surprising relationships Saddam Hussein developed with his American guards, and writing essays and op-eds — many about our nation’s civilian-military divide — for newspapers. I’ve thought about how the media could do a better job covering our ongoing wars as they approach their third decade. One thing is clear: The best reporting puts a human face on the implementation of our foreign policy, and with each passing year, there seems to be less of that kind of journalism. Only by communicating the humanity of the fallen — seeing them as their friends and families saw them — can the harsh reality of faraway war resonate back home.

Also important is communicating the humanity of the innocent people caught up in these foreign wars — and, while it’s more difficult, showing the humanity even of our enemies. The Saddam Hussein who was revealed to me in the course of the research and interviews I did for my book was a complicated, three-dimensional person. Was he guilty of terrible evil? Absolutely. But he was also capable of charm, humor, and even affection, to the extent that his avuncular demeanor reminded some of his American captors of their own grandfathers. It is worth considering whether the crafting of our foreign policy might have benefited had there been a better understanding of Saddam as a complex person rather than a cartoon villain.

Capturing the layered reality of overseas wars and foreign peoples is not easy. Journalists need time and access in a dangerous environment to report the detailed articles that are the most effective way to tell these stories. In recent years, as the military has sharply reduced opportunities for reporters to “embed” with deployed troops, it has become even more challenging. There was some degree of transparency in the early years of the “War on Terror,” when there were hopes that it would be resolved quickly and successfully. The military eagerly invited reporters to cover victories. Now, though, neither policymakers nor the military seem eager to advertise the tragic shortcomings of an unsuccessful foreign policy with bipartisan fingerprints.

Not only are there fewer embed opportunities, but the budgets of most print media have been slashed. This has resulted in fewer outlets being able to afford to send correspondents into danger areas, since the cost of a private security contractor and a driver alone can approach $1,500 per day. As a result, many journalists have been forced to put themselves in considerable danger as freelancers if they want to report from conflict areas. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, as of November, six reporters had been killed in Syria in 2019. Three of them were freelancers.

I confronted the security dilemma a few months ago when a magazine asked if I would like to return to the town I deployed to in Iraq 15 years ago to write about the experience. At one time this sort of assignment would have been a dream come true. Now, I declined.

As I weighed the danger of visiting an Iraqi city with active ISIS cells, equipped with only a modest budget to cover security and logistics, I couldn’t help but think of Jim Foley, John Cantlie, Austin Tice, and Steve Sotloff, courageous freelancers who traveled to Syria and whose abductions (and, in some cases, gruesome executions) are grim reminders of the dangers inherent in war reporting. What might have felt exciting when I was young and single now felt selfish as I imagined my wife and young son worrying about me from afar.

I suspect my decision was also influenced by creeping doubt in the ability of journalism to make a meaningful impact on foreign-policy discourse. The sense of idealism that had led me to volunteer to serve after the attacks on 9/11 had dissolved in the Iraqi sand. A similar sense of pessimism had begun to infect my thoughts on war reporting. Could the most talented and courageous journalist in the world file a dispatch from Anbar Province that would produce even a ripple in an America alternately anesthetized by pop culture and preoccupied with partisan political mudslinging? I don’t think so.

In the absence of a military draft, most Americans are understandably apathetic toward our wars. A recent article in the MIT Technology Review documents the paltry media attention devoted to Afghanistan, citing statistics from the Pew Research Center for Journalism and the Media that showed “Afghanistan accounted for just under 4 percent of all media coverage in the U.S. in 2010, when the Pentagon deployed 100,000 troops and dropped 5,101 bombs on the country.” Coverage is even more limited today — Pew no longer even tracks it as a topic.

The Pentagon and military leaders have also grown far less accessible. Pentagon press briefings used to be daily or weekly occurrences during the first decade or so of these wars, but recently there was a 15-month gap between on-camera, on-the-record press briefings.

Quality conflict reporting still exists: The courageous and artful work of C.J. Chivers of The New York Times and the freelancer Rania Abouzeid immediately comes to mind. But observing responses to it on social media and elsewhere sometimes leaves me with the sense that it is primarily reaching a closed community of service members and veterans, their families, foreign-policy experts, and a smattering of curious intellectuals and amateur historians.

In this climate of disinterest and limited access, how can journalists succeed in investing detached readers in the lives of strangers fighting in foreign lands?

The first step (and challenge) is simply to get there, learn about the place, and methodically develop relationships with real people. There is a critical need for more on-the-ground information to offset the disproportionate volume of airtime and ink devoted to the views of retired generals and think-tank pundits pontificating from afar. Only by journalists leaving the Beltway (and Twitter) and patiently observing these wars as they are waged in desperate corners of the world — interacting with the locals and the young soldiers — can they bring to life the real-world consequences of our foreign policy.

Once this foundation is established, quality war reporting should, as Chivers wrote, be more descriptive than prescriptive. Sebastian Junger’s brilliant documentary Restrepo, shot over the course of a year he and his partner spent embedded with a small infantry platoon engaged in near-constant combat on a remote mountainside in Afghanistan, powerfully captures the violent rhythms of life there without proffering any overt policy prescription. Still, the thoughtful viewer is likely to emerge from it with his or her own conclusions about the utility of the mission. Restrepo is a good example of the impact of a story being amplified by allowing the reader or viewer to connect the dots without being spoon-fed.

Travis’ unflagging positivity stood in contrast to my growing skepticism about our mission in Iraq. I would sometimes share these doubts with him, passing along articles that supported the misgivings I was feeling.

Social media make it especially challenging to capture the realities of conflict. A journalist’s “readership” and “social-media profile” are coveted by publishers and agents, but they’re increasingly tied to choosing sides in our fractured political landscape and then steadily feeding a partisan following the content it craves. It’s easier to make a name for oneself penning clever tweets about the president’s foreign policy than to spend weeks on the front lines capturing the complicated realities of war as they are experienced by real people.

So, then, why bother?

To me, the answer can be found in one person, Travis Patriquin, the young officer cited in the short death notice that began this essay.

Travis’ unflagging positivity stood in contrast to my growing skepticism about our mission in Iraq. I would sometimes share these doubts with him, passing along articles that supported the misgivings I was feeling. He’d invariably explain the progress his brigade was making in Ramadi, which made him proud; I would emerge from our conversation slightly embarrassed for having doubts in the first place, and reinvigorated for the work ahead.

Travis would not live to see the fruits of his efforts, as he was killed, along with two others, when their Humvee struck an IED in Ramadi.

The public’s appreciation of my friend Travis might have been limited to that 41-word announcement had not a journalist named William Doyle chosen to write a book about him: A Soldier’s Dream: Captain Travis Patriquin and the Awakening of Iraq. I don’t know how many people bought the book. It was not a bestseller, and it did not have a demonstrable impact on the debate over the Iraq war.

But I can only hope that its readers emerged from it with a better understanding of what these wars are like on the ground, and how efforts by extraordinary individuals like Travis, far from the corridors of power, can help shape history. The book serves as a reminder of how these deaths in distant lands can leave a crushing emptiness in the lives of some back home.

I am reminded of the author and decorated combat veteran Elliot Ackerman, who in response to being asked by curious Americans if he had ever killed someone would respond, “If I did, you paid me to.” Likewise, we were paying Travis’ salary, paying for the food he was eating, paying for the weapons he was using and for the Humvee in which he was killed. Whether we like these wars or not, these soldiers are in harm’s way because of us, our engagement (or lack thereof) as citizens, and ultimately our behavior at the ballot box. We owe it to them to try to learn what they are doing, why they supposedly are doing it, and to use this understanding to reclaim ownership of our foreign policy.

No responses yet